How a historic monument can lose its identity. Destroying "minor" heritage

One of the tendencies of modern heritage conservation is to consider that it acquires its infallibility by being eminently subject to scientific rigor, to quantifiable truths, an undeniable truth based on an unprecedented expansion of the capacities of investigation of the work of art, of the substance that makes up heritage in its broadest sense.

However, action on heritage is increasingly being affected by a contradiction between the depth and breadth of scientific research and the quality of the work of restorers or conservators. The built heritage is, by its very nature, affected by this weakening of the research-intervention relationship.

The above comments bring to mind what was strongly stated in the forgotten or rather ignored Presidential Report on the BuiltHeritage1 - namely that the protection of monuments, historical and archaeological sites cannot be conceived without the synergy of all the system's links, from legislation to in situ intervention or preventive conservation. Without such synergy, there is a major risk of irreversible corrosion, leading to the ultimate destruction of the heritage's identity. And in place of the authentic body of a building or a work of art: an irredeemable surrogate. One of the ways in which the built heritage can irreversibly lose its authenticity is through the destruction, mutilation or falsification of those components of a building that we call artistic in the desire to isolate them in a distinct category with a special status2. The subversive intention to give them a degree of 'mobility' and perishability that is accentuated in relation to the building's immobile body often seeks to blur the inseparability of these components while diminishing their essential contribution to the identity of the built heritage. From the decorative 'epidermis' of the historic monument to the functional elements, a whole inflorescence of details which elegantly and finely define the style of the building is lowered into the sphere of the 'minor'. Here, a permissiveness that escapes any legislation means that the 'minor' heritage can be replaced, mutilated, arbitrarily moved and, ultimately, destroyed. This ever-expanding reality, which basically concerns an entire policy of safeguarding the built heritage, which is increasingly in the surviving condition of rehabilitation, has prompted us to take up our observations on the fate of the 'minor' heritage.

In the aforementioned Report on the state of the built heritage, we defined the main causes of the decline of the activity of protection of artistic components within the complex operational ensemble of conservation and restoration of historical monuments:

1. the absence in many cases of an adequate integrative vision of the artistic components already at the design stage of conservation-restoration of historical monuments;

2. the arbitrariness of aesthetic choices regarding the remodeling or simply the suppression of decorative or functional elements that define the interior and exterior space of the architecture in a unitary and inseparable way;

3. the pre-eminence of architectural form and structure as an argument for the depreciation of appearance, the simplification or elimination of the modenature, treated as a surrogate, with perishable materials, foreign to the original substance;

4. inadequate treatment of the 'epidermis' of historic monuments, ignoring the way in which its plasticity, from color to texture, contributes to the perception of the authenticity of architectural surfaces.

The development of these landmarks of the decline in the preservation of the authentic architectural image leads us to formulate a diagnosis of the current state of the built heritage.

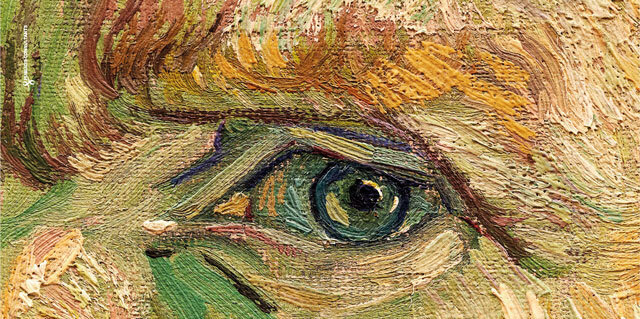

The conceptual error, which has already emerged at the stage of the conservation-restoration project of a historical monument, starts from the treatment of architecture, structure and artistic components in registers of different status. The Brandian concept of equal treatment3, irrespective of the category of the work of art on which we have to intervene, is sacrificed in favor of the pre-eminence of architecture together with the principles governing the survival of built heritage in the conditions of contemporary society. Survival is increasingly conditioned, without deontological hesitation, by the methodology of adaptation4, often involving a hypocritical imitation of the contemporary functions of historic buildings. It is a compromise that develops at a fast pace, with a whole procession of sacrifices made to authentic details, from the 'epidermis' of facades to the polychromy of stuccoed interiors or the elegant functional elements of the 'minor' that define the style of the building by their sum.

A number of methodological aspects responsible for distorting the authentic message of the built heritage can be cited in this connection:

- The uncritical and abusive replacement of the "epidermis" of a historical monument, from mere plaster to mural decoration, with new plaster and paint, arbitrarily applied, with a chromatic and texture foreign to the original plasticity of the architectural surfaces;

- restoring the decorative 'text' of facades using surrogates and pseudo-techniques, balancing confusingly between the principle of reversibility in restoration and the precariousness of a kind of 'arte povera';

- the strategic avoidance of stratigraphic research at the level of the mural 'epidermis', thus eliminating clarifications in the restitution of the monument which, like archaeological research, restorers of artistic components could bring to the restoration of the monument

- the adoption of conservation-restoration methodologies for the built heritage in which the restitution of the architectural form does not imply the preservation of the authentic substance of the building as far as possible.

A quick glance at the evolution of the protection of the built heritage brings to mind the statement that Professor Grigore Ionescu made in the 1960s about restoration "nowadays"5: having left the strict tutelage of "historical restoration", intervention on the built heritage considers it legitimate to adopt creative initiatives capable of restoring the incomplete image of a historical monument.

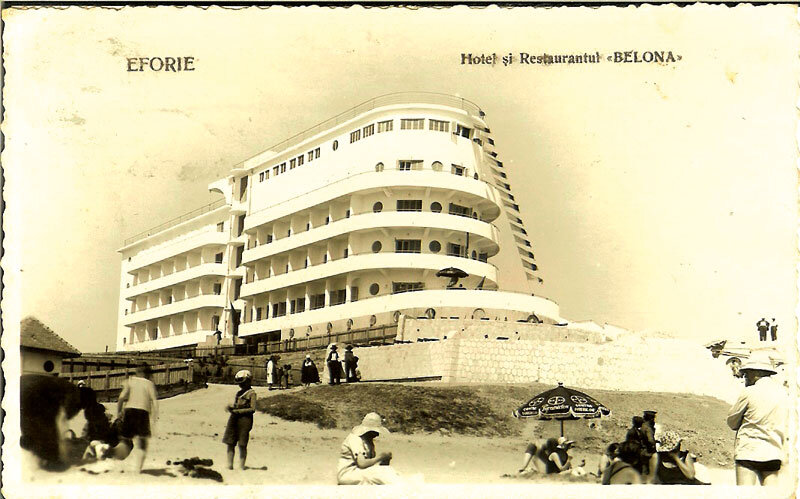

The result of this attitude has been the conviction that, at the level of architectural details, it is possible to produce a modern remodeling that dialogues with what remains of the authentic construction. An eloquent example of this is the Dragomirna monastic complex.

A visible desire to purify the space, to express sincerely the material structure of the architectural volumes, has generated a restitution of the historical monument under the pressure of the contemporary values analyzed by Riegl6. In such a condition, the 'minor' heritage, hitherto indestructibly linked to the authentic substance of the historic monument, acquired a precarious status, subject to the oscillations of taste. Underestimating, for example, the archaeology of architectural surfaces or ignoring its results, especially when the 'mural epidermis' is the bearer of an extremely rich message, from the imitation of the parament to the iconographic program, may have led to irreparable losses. The slippage from the rigors of Brandian criticism, in which the decision to intervene, based on scientific grounds, results from the confrontation of the two instances, historical and aesthetic, in extremely permissive forms of restoration-adaptation, has recently generated catastrophic transformations of the built heritage. The historic center of Bucharest is the most expressive victim: the rapid and chaotic transformation of the historic monuments that used to survive in the historic center into a profitable decor that evades the criteria of authenticity. At the same time, under the pressure of the city's new functions, the chance to preserve the archaeological remains of the medieval city in parallel with 19th and 20th century Bucharest has been suppressed.

Here are briefly a few current gestures that lead to compromising the authenticity of the built heritage:

- The uncritical and brutal stripping of the original finishing plaster, the polychromy of facades and interiors, the authentic mural decorations, even if fragmentary, the artistic elements in stucco, terracotta or stucco-marble;

- the absence of simultaneous and equal concern for the exterior and interior of the historic monument, the survival of the exterior image being guaranteed only by radically adapting the interior and selectively destroying or preserving the artistic components;

- making the rehabilitation of the historic monument conditional on the possibility of arbitrary replacement of the functional elements which at the same time define the style of the building; the absence, moreover, of a conservation-restoration program for these details, which are part of the 'minor' heritage;

- the restitution of architectural surfaces outside any historical reality, often according to the strident fantasies of the client;

- the simplification or falsification of the original modenature of facades, in full collusion with the policy of thermal rehabilitation of buildings.

Now is the time to make a few more points on the ambiguous policy of conservation, falsification and destruction, which attempts to convince us both of the fairness of the proposed solutions and of the absence of an alternative, and therefore of the futility of a dialog. The suppression of the 'minor' heritage that a historic building possesses is generally followed by the practice of surrogates. In other words, the stripping away of the original artistic and functional elements of a historic monument is followed by their pseudo-reconstitution, often in a simplified form and especially in precarious materials, veritable butaphors of the moment. This is a way in which, for several decades now, the traditional trades, which Romanians were privileged to keep alive, have been breaking away, without any concern: bricklayers, plasterers, carpenters, carpenters, blacksmiths, blacksmiths and stonemasons are becoming fewer and fewer or disappearing. Modern surrogate craftsmen play a key role in this disappearance. One of the most significant examples of this expansion is the use of polystyrene in the restoration of historic buildings. The extreme reversibility of this material is confused with its distressing precariousness, which is more suited to temporary decoration.

The use of surrogates in the case of "minor" heritage can be insinuated into the apparent effort to find the most effective materials and technologies for the conservation-restoration of historic monuments. The onslaught of synthetic materials in restoration, supported by the effervescence of the building materials industry, easy to install and always accompanied by the spectacle of publicity, have led to the bankruptcy of historic materials such as lime and clay. The replacement of traditional materials with synthetic substitutes is not only a fatal blow to historic crafts, but also the destruction of an ecological balance that once existed in the built heritage area; the lime, stone, clay and wood used in historic buildings were in harmony with the natural environment.

The loss of the authenticity of the built heritage is taking place in the context of the installation of a veritable renewal mania to which the artistic components and functional details of historical monuments fall victim: mural paintings, stucco and stucco-marble decorations, door and window frames with original fittings, elegant stoves, painted panelling and ceilings, skillful imitations of wood, mosaic paving and stained glass, ironwork, all in a refined stylistic unity. One of the factors responsible for the systematic destruction of this "minor" and substitutable heritage is thermo-panpanomania. From the medieval heritage to the vernacular architecture of the 19th century, from rural heritage architecture to churches, the presence of double-glazed windows constitutes a breach in the stylistic unity and authenticity of a historic monument.

A final point concerns the existence of methodological conflicts whereby elements that play an essential role in what Brandi called the 'epiphany of the image' are hastily sacrificed in the name of saving the structure. The solutions proposed to strengthen the structure of historic monuments sometimes all too easily require ancillary operations to remove mural decorations or simply to remove them and replace them with surrogates. This leads to a new hypostasis of destruction: the existence of a building that has been rendered ecorchised, stripped of everything that characterizes its image. Left standing, the walls thus bear the stamp of an irreversible downgrading.

Notes:

1 Report of the Presidential Commission for Built Heritage, Historical and Natural Sites, Romanian Cultural Institute, September 2009

2. The concept of artistic components is defined by Law 422/2001 on the protection of historical monuments, in Art. 3, point a

3. Cesare Brandi, Theory of Restoration, Ed, Meridiane, Bucharest, 1996, p.179

4. The term is introduced by Bernard Feilden, in Une introduction à la conservation des biens culturels, chap. 3, ICCROM, Rome

5. Grigore Ionescu, A New International Charter on the Conservation and Restoration of Historical Monuments, in "Monumente istorice. Studii și lucrări de restaurare", Ed. Tehnică, Bucharest, 1967

6. Alois Riegl, Le culte moderne des monuments, Ed. Du Seuil, Paris, 1984, p. 87.

Dan Mohanu

Expert restorer in the field of conservation-restoration of mural paintings. University professor, coordinator of the study program Conservarea Operei de Arte in the Department of Art History and Theory of the National University of Arts in Bucharest.

Published works:

Mural Extraction. The Romanian Case, Historical Monuments Commission Bulletin, 1995;

Preface and Glossary to "The Theory of Restoration", by Cesare Brandi, Ed. Meridiane, 1996;

Extraction of the mural paintings from the Argeșului Cathedral from the second half of the 19th century, in the catalog of the exhibition "Frescoes from the Argeșului Cathedral", National Art Museum of Romania, Bucharest, 1998;

Some considerations regarding the researches at the Domnească Church of Curtea de Argeș. Timpanul de vest al naosului și inscripțiile descoperite, D. Mohanu, Constantin Bălan, in "Revista Monumentelor Istorice", year LXI, no. 2, 1992;

La traduzione rumena della Teoria del Restauro di Cesare Brandi, in the proceedings of the international congress entitled

"La teoria del restauro nel novecento da Riegl a Brandi", Viterbo, November 12-15, 2003;

Art, Culture et Foi dans les monastères orthodoxes, in the proceedings of the international colloquium on "Abbayes et Monastères aux racines de l'Europe" (Conques), Les Edition du Cerf, Paris, 2004;

Mesajul lui Vasile Drăguț, in "Revista Monumentelor Istorice", 2005;

La traduzione ruemna della "Teoria del Restauro" di Cesare Brandi in the volume "La Teoria del Restauro nel Novecento da Riegl a Brandi cura di Maria Andaloro", Nardini Editore, 2006;

The Stone Crows. Studiu interdisciplinar, Editura Univer-sității Naționale de Arte, București, 2010, co-author;

Spaces with a specific morphology of mural paintings degradation: the porches of orthodox churches, Caiete ARA, Arhitectură, Restaurare Arheologie, Nr. 2 / 2011, p. 183-193;

Archaeology of the mural paintings from the Church "Sf. Nicolae Domnesc" in Curtea de Argeș, ARA, Bucharest, 2011, 517 pages with illustrations.