Busy being born

In the summer of 1964, Bob Dylan went electric.

It happened during the songwriting sessions for "Bringing It All Back Home," which is now considered one of the greatest albums in rock history. Dylan's style evolved from acoustic solo performances to accompaniment with electric instruments. Dylan's earlier protest music gave way to complex, surreal lyrics. The world had yet to get used to Dylan's constant process of artistic self-reinvention. By drastically altering his style, Dylan risked being shunned by his fellow musicians in the folk-rock community, ridiculed by some critics and hostile to his fans. And yet he ventured into uncharted musical territory, stepping outside his comfort zone. One critic concluded of the album, "By fusing the Chuck Berry rhythm of the Rolling Stones and Beatles with the left-wing, popular folk revival tradition, Dylan really brought it back home, creating a new kind of rock & roll [...] that made rock available to every kind of artistic tradition"1. Dylan introduced us to an unheard of world. He would continue to do so for the rest of his career. To use a clumsy metaphor, his entire oeuvre could be seen as a journey through a classic ring of wide-open rooms, each room revealing a unique and radically different lyrical and musical world. As an architect, I think in spatial terms: Dylan is neither an isolated room nor the sum of these rooms; rather, Dylan is like a dandelion seed carried by the wind through this succession of rooms, sailing on a "sea of possibilities". Architects, and I am no exception, are notorious for their inability to write. Rather than bother trying to paint romantic portraits of dubious taste, I will let the poet describe himself: "When you're not busy being born, you're busy dying"2, he says in one of his verses.

It's no coincidence that this quote comes from the album that started it all, Bringing It All Back Home. Dylan understood that being complacent is synonymous with starting to die. The lyric is perhaps the most expressively composed argument in rock history about the value of living a life of constant choices and constant transformation. Rachel Kushner, a Dylan fan and a writer I hold dear, reflected on it, "The point is not to be born, but to be reborn: in a state of constant renewal, rejuvenation, replacement, change. [...] You are busy being born along the first long ascent of life and then, having passed the maximum peak, you are busy dying: this is the logic of the text, its syntax, as I interpret it. "To be born" is here an open and existential category: the acquisition of experience, an intense living of the present, after which follows the long period of life in which a person is done with the new"3. I do not think that the concave graph illustrated by the author refers to the accumulation of biological age, but to the ability to remain creative. "Done with the new" has nothing to do with age and everything to do with one's own philosophy about life. Conservatism opposed to visionary; being busy dying versus being busy being born.

Is there a better definition of Mannerism than being "busy dying"? Or, if I am to fall into the trap of binary opposites, is there a better definition of the avant-garde than being "busy being born"?

What else is it to be a visionary if not to be pioneering, innovative, discovering, experimental, unconventional and reckless, fallible or even foolhardy?

I should have written about the visionary projects that competed in the biennale. Instead, I wrote a text about how Dylan became electric. Sure, the provocation was intentional, but the message isn't that far-fetched, is it? I could have started like this: "In the summer of 1964, Ron Herron drew Walking City for an obscure fanzine called Archigram 5: Metropolis." Please notice the logo of the visionary projects section. The conclusion would have been the same, but you have to admit that the Dylan introduction is much more engaging.

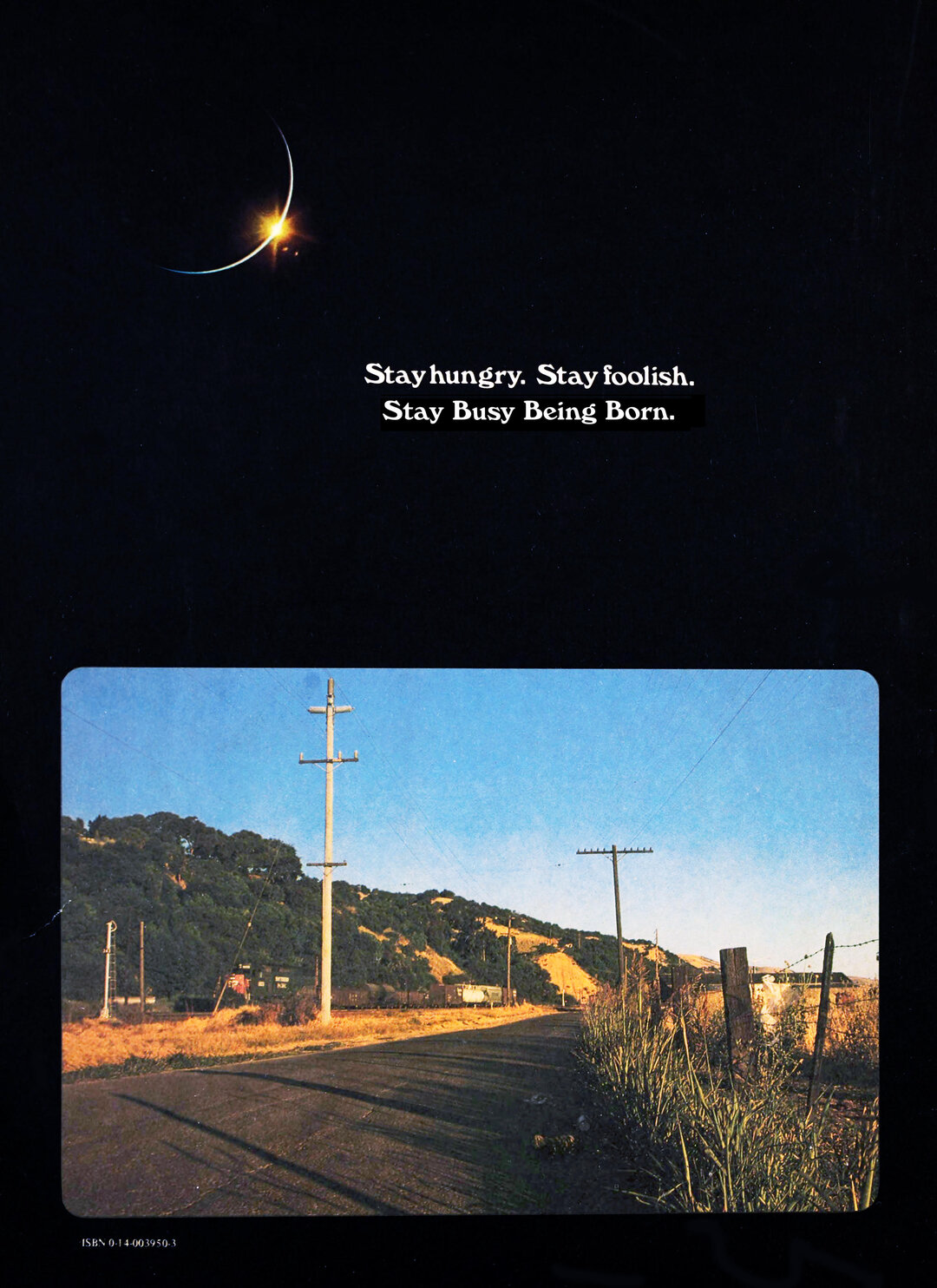

Still, what is the conclusion? What is my message to you (readers, biennale organizers, participants in the current and future biennales)? I generally refrain from absolute verdicts and sharp statements. Instead, I'll quote a true visionary, a guy so obsessed with Dylan that he invented the iPod so he could carry the master's entire discography, including all six volumes of the musician's bootleg bootlegs, in his pocket. He puts it this way: "Your time is limited, so don't waste it living someone else's life. Don't get enslaved by dogma - that's living the conclusions of other people's thinking. Don't let the noise of other people's opinions drown out your own inner voice. Most importantly, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you really want to become. Everything else is secondary"4. And if I may, I would like to end with a somewhat inevitable paraphrase: "Be hungry. Be reckless. Be busy being born".

Fourth cover of Whole Earth Epilog (San Francisco: The Point Foundation, October 1974) modified by the author

NOTES

1 Dave Marsh, The New Rolling Stone Record Guide, New York: Random House, 1983, p. 154.

2 Bob Dylan, "It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)," from the album "Bringing It All Back Home," Columbia Records, 1965.

3 Rachel Kushner, 'The Hard Crowd', in. Essays 2000-2020", New York: Scribner, 2021, p. 228.

4 Steve Jobs, "Speech for the 114th Stanford University Commencement", Stanford University, California, USA, June 12, 2005.