For me, tradition is not the path my grandfather walked, but the direction he would walk today

A small town of 18,000 inhabitants is home to one of the most award-winning architectural offices in Romania: Larix Studio - recipient of more than 20 awards and nominations at the Architecture Annuals and Biennales. The founder and head of the office, architect Köllő Miklós, was awarded the Hungarian Academy of Art's Award for Architecture in 2020 (in recognition of the value of research on the morphology of the settlements of the Secler settlements and all the work for the protection of local architectural values, promotion of wooden architecture, architectural creation and mentoring), and in 2021 with the Ezüst Ácsceruza Prize - under the care of the Union of Hungarian Architects, which recognizes exceptional merits in the field of architectural journalism/writing.

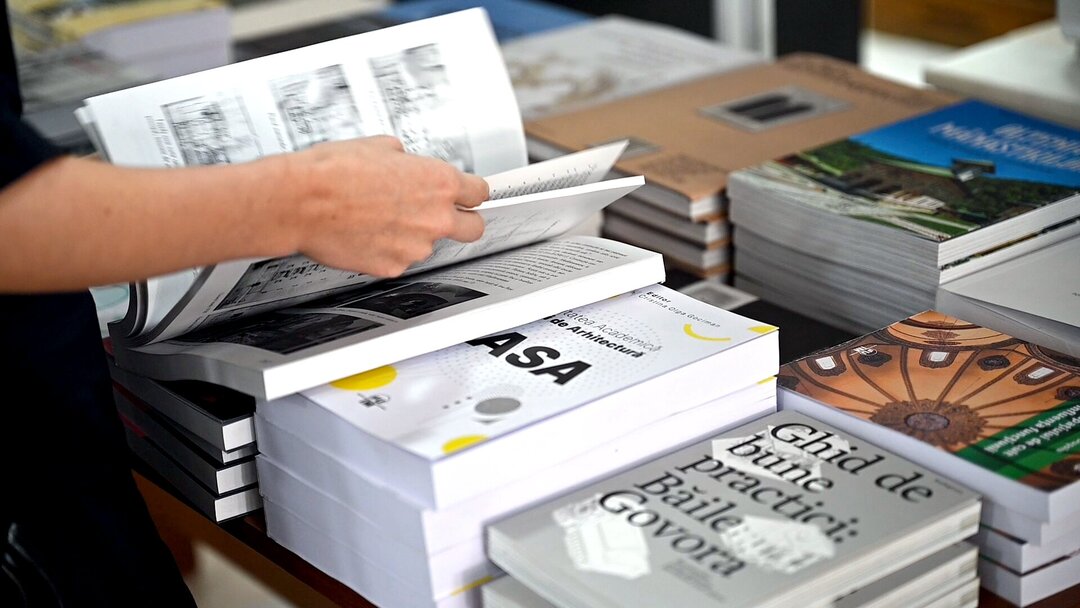

I met him at the Calderon office on the occasion of the exhibition organized by the UAR at the launch of the book "The Story of My House" - which tells the story of the transformation of his grandparents' house and the move to his native village Ciumani, while also presenting the principles of an architectural work diverse in subject and scale, but extremely unified in its relationship to the landscape and the use of woodworking techniques that continue the local tradition. The author describes his characteristic approach as contemporary regional architecture and the buildings, which sit naturally in the landscape, are clearly of the place. It is, however, a regional architecture without resorting to decorativism or passalistic formulas, without exactly copying historical models, but with a deep understanding of the becoming of a lived tradition.

Köllő Miklós Köllő Miklós is a remarkable personality not only for his architectural creations and his restoration and urban planning works, but also for the multiplicity of his concerns and interests, which make him a contemporary "homo universalis". In order to understand more about an exemplary (but not without difficulties, which many young architects have had to face) path, I visited him at the Larix Studio office in Gheorgheni. I had the joy of discovering a professional with a clear sense of duty towards the community to which he belongs, with a deep gratitude towards those who formed him (family, teachers, educational system), an architect who sincerely enjoys the results of his colleagues and who treats with commitment and seriousness the role of mentor of the younger generation.

Gheorgheni is a small town with a typical image of a Transylvanian settlement: a charming center with a small square surrounded by historic fronts dominated by Art Nouveau, imposing 18th century churches and the huge early 20th century building of the Salamon Ernő High School. The city also has three small collective housing neighborhoods (which make you wonder why you would live in a block of flats in such a place) on the same side of the center, but when you move away from the central square, the urban image is taken over by mostly ground-floor houses lying numb in huge courtyards and gardens. It's a cold and foggy early November, and the chimneys of the roofs, lost beneath the rusty foliage, are already smoking.

The Larix Studio building is in the central square and has a shop on the ground floor. I enter through the gang. In the back yard, a middle-aged man is chopping wood.

- I'm looking for an architectural firm....

- Larix Studio, it's here - and he shows me a small side door, ajar.

I knock.

- You must call - he warns me sternly.

I do.

- Come in, please, we've been expecting you!

I go up a narrow staircase and enter the reception-archives, a whole wall lined with project files. We are talking in an adjoining presentation room, where a screen scrolls images of the studio's work. Two graphic works and a tapestry signed by Köllő Margit (the architect's aunt) hang on the wall next to the discussion area.

- Your office needs no introduction. As Ileana Tureanu said at the opening of the exhibition at the UAR headquarters: you didn't just win prizes at the Biennials where you were on the jury. It's one of the offices that do the most beautiful rural architecture, a rural architecture very anchored in the contemporary world, an architecture that is not at all passista, a very present architecture and, at the same time, you also do some exceptional restorations. I don't know where the sources of these formidable results are, but I suspect that part of it is in your origins - one couldn't be more local - and part of it is educational. Tell us a little bit about your local, biographical and educational background that led you to architecture.

- It should be noted that all the colleagues I work with in the office have left and come back here - both fellow engineers and architects. Basically, the fact that the area itself is a mountainous area, with some stricter rules, regarding the roof - snow, winter and so on - anyway pushes an architecture in such areas towards regionalism. If we look at regions with similarities, at Voralberg or Switzerland in general, we see that wood and slopes are characteristic. The snow problem exists... that is solved with flat roofs, like in Switzerland... climatic factors push towards regionalism.

Our tradition is wood, that's what we've worked and that's what we're still working on. There is a duality here, because wood, on the one hand, is a traditional material, on the other hand it is a very contemporary and modern material - because it is a renewable building material, it is a low embodied energy material; however we look at it, we can consider wood as a fashionable material. In practice, then, wood is both tradition and contemporary fashion. This situation where both tradition and modernity are linked to wood raises questions. What is tradition, after all?

Everyone thinks it's something fixed, that is, nothing changes. We have made many surveys and inventories of the Harghit villages in the area. I think that it is essential for an architect working in an area to do a lot of research and to be on the ground a lot, to understand what is happening in the area.

- But it is also important for this understanding to come from within, You have a sentence in the book, towards the end, which I liked very much, where you say: for me, tradition is not the path my grandfather walked, but the direction in which he would walk today. And for that you need an insider's knowledge, not necessarily something analytical, something external.

- So, along with the urban plans, these inventories of local values should also be made and this is a good opportunity to get to know the countryside. Field research, if it is combined with archival research, the person who deals with the subject realizes very quickly that traditions are changeable; that is to say, everything that is useless disappears from tradition and everything that is today's innovation can somehow become tomorrow's tradition. For example, we have pictures from Sândominic, from the 1960s, where the houses were covered with shingles and shingle and had steep slopes, and today, in the same area, there are houses with tiles, with lower slopes and chimneys, and still traditional. We are in Gheorgheni, an Armenian town, partly an Armenian town, and a town that thanks to the Armenians became a city, but if we look at the pictures of the time and especially if we look at the 1909 city bylaws, we discover that the bylaws, on the one hand, prohibited the use of straw and planks as roofing in the central area - not to mention that straw roofing was also prohibited in the outer areas - but instead 800 bricks were offered free of charge to those who wanted to build chimneys.... so the chimney, which we can't imagine never existed...

- I understand that its absence is a tradition in the old houses of the old Szekler.

- That image of the city center of Gheorgheni, which we say is historical, is not really so; it's only a hundred years old; we say it's traditional, but it has changed. So tradition is not set in stone - that is the essence. The question is whether there is continuity, and if there is continuity, things flow from each other. We have many vernacular monuments, I would say traditional - vernacular means made by the hand of the man who lives there, only here they are made by the hand of the man and in the clacă, but, in fact, these people worked in wood and they were very skilled carpenters, who worked all over the region and even reached Bucharest, as far as Constanța, as far as the ports, as far as Hungary, so they were renowned and sought after.

- They still are. There are a lot of people who work with Secler carpenters.

- Yes, so in that way it's high-tech at the vernacular level, so to speak. If these traditional crafts that led to that architecture disappear, then we no longer have the chance today to restore these monuments authentically. Because I remember - and as a child I took part in many of these works - how the beams were carved on the spot by a certain grandfather, a certain grandfather, a neighbor, a relative. Today, if a beam like that were to be carved, that beam would have to be carved by someone who has a doctorate in wood carving. I mean, that would mean a very expensive piece, because it's made by a carver, but by a carver who sees the surface and doesn't see the life of the wood - how it's going to behave over time and how it's going to stand up to the effort. In short, if we lose this knowledge and this practice, then we will restore these monuments or, increasingly, houses that are not monuments - but many people prefer to stay in such houses - we will rehabilitate or restore, as the case may be, more and more badly and authenticity will be lost. So, somehow, these crafts should live and this is not happening, they are not considered as intangible heritage. Then the only possible way is to find an architecture in which they have a say. In other words, what they know and what they produce should be kept alive so that we can call on them when we need them. The shingle, the shingle should be used in as many places as possible, so that the craft can continue to exist, to be used when needed. So, if shingle can be put on the sheathing with an airy layer, why can't it be put in the bathroom over the bathtub?

- I've seen it can be done in your house.

- We can ask other questions like that, so somehow this potential is there and does not need to be reinvented, because it is still alive. It's a very big advantage as the world rediscovers traditional crafts. In this post-postmodern world in which we live, everything is handicraft: from yogurt, which for some reason ends up being handmade... but let's face it, maybe the little things...

- It's a sales strategy a lot of times, but yeah.

- It's a gateway of time; today, when we appreciate these crafts, they, with us, exist as relics of the pre-modern period and can contribute to the wood architecture of the area. I mean, yes, of course, we all dream of high-tech, but if I have no way of getting there, I look at what I can do, how I can make something out of what is local, with the materials here, and I discover that it can be done, a little differently, with more poverty, more skill, but that is also tradition. I mean, the tradition is that I don't change the material with which I work; if I have worked with wood up to now, I will continue to work with it.

- As much as I can and as much as I can afford.

- I'm not saying this is low-tech.

- No, but it's mid-tech.

- Yes, an intermediate can be that and it's somewhat honest. I don't understand those contractors who market wooden houses and live in brick houses. The point is that, in the end, tradition and traditional and modern technologies complement each other and perhaps perform better together.

If they lose tradition, they lose their roots, if they don't step into the contemporary... Churchill said somewhere that art without tradition is like a flock of sheep without a shepherd, and without regard to contemporaneity - it is like a corpse.

- So here we are. Those would be very broadly the ideas behind the architecture that you practice. I can see that you are avoiding the biographical part a little bit, but I am not going to let you avoid it because, this time, it seems to me to be very important. So you were born in Ciumani?

- I was born in Ciumani, in a family that had quite a lot of intellectuals and artists. I think I can say that I was born into a family of artists who... On the other hand, they weren't all artists, maybe many were craftsmen. My father was a mechanical locksmith, but my grandfather worked with wood: tubs, barrels, wheels and so on, and I had the chance for a few years when I was a small child to work in the workshop, I mean, to play with the tools. My grandfather used to tell me things that I thought were poems: how the wood is oriented and why he put it that way. Maybe I memorized these things as if they were texts, without understanding very much of them, but gradually, gradually, working with my father and observing how the materials behave, these messages of grandfather were understood, they were not said in vain. Wood behaves over time, it behaves to moisture, it's just that this movement is 90% predictable, and this predictability is what is missing in the approach of many, and it basically means prolonging the life of that material. So there I lived the life of a family where they worked, during the eight hours, my father at the enterprise, my mother at the local cooperative, and then they raised animals, worked in the fields, so I understand the landscape maybe from other aspects than as a pretty picture. All the time, from the second grade, from the fifth grade, from the eighth grade, those from the art school in Târgu-Mureș, because, at that time, there was one there, they wanted to take me in the direction of fine arts. Except that my aunt, Köllő Margit, who was a textile artist and graphic designer, said that at that time - the communist period - being a plastic artist was quite risky, it was not a safe profession, so to speak (especially in the context of being of "fellow country" nationality). So the requests were dismantled one by one by my aunt's insistence and so I ended up at a math-physics high school in Miercurea Ciuc, which I don't regret at all, because architecture is physics and mechanics, and it served me well in college.

- Here we'll have a discussion about architecture high schools because... we'll go into more detail later, but I also think that for an architect, a good general knowledge high school doesn't hurt.

- Meanwhile, I was always drawing.

- Your aunt didn't forbid you.

- No, no, she helped me in that sense, but not institutionally. It was also a family life, a lot of people came to visit us and so a relative of my mother's, Szász Lőricz, who lived in Iași and made the Romanian-Maghrebian dictionary used in that period, in the 80s and 90s, asked my parents for the first time: "But why don't you give your child to Architecture?". He, living in Iași, also caught the era of architecture in the 70s.

- Porumbescu was there, building...

- There were many, many there... and that was in tenth grade, and from then on I trained in that direction. There were 50 places in Architecture and I was in the math-physics class, the headmaster asked me, in every class, what I wanted to do, and I told him architecture, and he told me: come on, you don't have a chance, I don't know what...

- What encouragement!

- No, they were realists, they knew that if I didn't get into the army...

- It was a pity, two years in the army.

- Yes! And there was a high school where out of 36 in the class, 36 went to college and, in a way, we were worried about what would happen, and I, to get away from that, at one point I said I wanted to be president of the country.

- Not bad!

- And then they left me alone. And so I started tutoring in Bucharest, traveling by train a lot.

- Out of curiosity, who did you tutor?

- I started with Arpad Zachi (Arhitext). He used to come to Brasov, he got in touch with artists' circles, with Ábrahám Jakab, with my aunt, who was living there at the time, but then I continued with Zoltán Takács and there was another young man with him, who drew divinely, he went to Canada, I can't remember his name, but he taught me a lot. Somehow, from that moment on, Mr. Takács became a kind of mentor, who followed me all through college, even after. Of course, in the younger years he wasn't, there were Mr. Mihai Cocheci and Zeno Bogdănescu. In the meantime, I was very interested in puppeteers and I had a friend at the university from Maramureș, and Animafilmul, which was run by Zeno, at a certain point, gave me the opportunity to see this side of the profession, but also the drawing, because they worked by hand at that time.

- How beautiful and expressive is (talking about the relation with the cartoon) the video you have on the company's Facebook page, with the evolution of the locality.

- And I also remember discussions with Mrs. Cristina Olga Gociman, who was an assistant to Mr. Cocheci, there were live discussions on the subject. Then I had the chance to get a scholarship with Tibi Florescu and Stefan Ghenciulescu in Belgium. There were four of us, with Tibi and Vinicius Răducanu, with whom I served in the army, and Stefan from the first year, we were basically the four wheels of the cart. That was our nickname, because we did everything together. It doesn't mean that we did the projects and the same project came out, but since a course had a bibliography, we divided the bibliography into four and each of us read that part. And here I have to talk about another line, which was not really the one represented by Takács, but that of Mr. Corneliu Ghenciulescu, who was a believer in accuracy and in relating to the context.

- He was an exceptional teacher. I also had him as a teacher in my workshop.

- And I worked a lot, talking with these people: Takács Zoltan Takács, Radu Teacă, Corneliu Ghenciulescu, Zeno Bogdănescu, Dan Marin, Mihai Cocheci... somehow, in the school, they were these people who... Well, not to mention the Department of Urbanism, with Constantin Enache, Florin Machedon and Sandu Alexandru, Rodica Eftenie, Peter Derer. Then, in Technical Sciences, Mircea Crișan and Mr. Professor Cișmigiu (he still had an optional course), I liked it very much. There were people like Ana Maria Zahariade, Nicolae Lascu and so on.

But this scholarship that I mentioned earlier, in my third year, was still a chance to see in reality what I had learned in the History of Architecture; I saw a lot of it.

- Where was the scholarship exactly?

- It was in Belgium, sort of, Belgium, Holland, Germany, later France - they became accessible to me and I was able to see a lot of the buildings that I had learned about in History of Art, but also a lot of contemporary architecture that I had seen in magazines and that was being discussed. On the other hand, the school in Liège had a different approach to this profession, i.e. with us, functionality and the traditions of modernism were very present, whereas with them, poetry and philosophy and what lies behind it, i.e. the approach, were much more important than the end result. And that, somehow, when I came back, even to this day I can't forget that the most heated discussions with Mr. Takács were precisely because I was somehow penetrated by this virus of the approach and the context.

- It was a rather non-contextualist architecture, to use worse words, at school, an architecture very concerned with the object and with linking up with everything that was moving abroad.

- What belongs to Mr. Takács belongs to him. He had very characteristic, very beautiful glasses and he said: "Design it is! Look at these glasses!". I said, "Professor, can I borrow these glasses?" And I put them on. "But, look, they don't fit me!" And he laughed, he understood and said, "Come on." And in my diploma thesis, which was the Roman Catholic Church in Miercurea Ciuc, it was precisely this context analysis and contextualism that was not only accepted, but even encouraged by Zoli. And I did Structure with Cișmigiu, because I had been to his course, which was an optional course, but it was a very good course.

So much for that about training. Then, after I finished "Ion Mincu" in Architecture, I did a master in Urban Planning, also at "Ion Mincu".

- And then you went to Cluj, Restorations?

- Postgraduate school in Cluj, restoration. That was until about 2006, and from 2017 I enrolled in the doctoral school at "Ion Mincu" - which I don't understand why it's PhD and not DLA - with Mr. Nicolae Lascu, and now, basically, somewhere in January, it will be the public defense; the rest I passed.

But Bucharest also meant for me the Department of Design with Marius Marcu Lapadat, and the Department of Urbanism, where I managed to understand the city. I love Bucharest; I often miss it, and when I come back, I do it with great pleasure.

- It's a very complex city and there are many people from the Transylvanian region who don't know it and say: Ah, Bucharest is impossible!

- I also see the other side of the city. Now that I've got used to the countryside, I don't think I could live there, I wouldn't go there on purpose, but Bucharest is not the problem, it's the big city; I mean, the crowdedness.

- Distances, lost time...

- But on the other hand, there are theaters, cinemas, cultural life...

In the meantime, I've been making old music for almost 10 years, with Mrs. Öllerer Ágnes, with Macalik Arnold, who is an architect in Cluj and has many achievements, and with other friends. We did a lot. I did the Ady Endre Press College in Oradea. I finished as a photojournalist, but I don't practice this job... except with the phone, now, that's it.

- So some studies in many fields... and long, so...

- And hobbies that keep changing. There was horseback riding for a while, experimental archaeology on light knighthood techniques. Nah, and now, I've rekindled an old love, making musical instruments. I have a series called "musical instruments that may never have been - but could have been". It's still architecture, because the shape... It's interesting that a lot of these instruments are pumpkin-shaped.

- The sound box.

- Yeah, and then I make a few. Now I've started making a couple of instruments, where it's clear that they were later made of wood, but I suspect they were originally made of pumpkin, and I'm making the pumpkin version.

- So like that, musical instruments that maybe never existed. That, as Makovecz said he was doing archaic architecture that maybe never existed. You, as far as instruments...

- Frozen music, though. Architecture.

- It's one thing with the small object and another with the large object, and it's a point in the discussion we'll come back to.

I don't suppose you've ever questioned not going home?

- No, it wasn't so firm for me. I got on very well with Tibi and Stefan - because Vinis had gone to France in the meantime - and Tibi was in the Department of Urban Planning, so, on this route that everybody knows, Stefan very quickly also went to the Department of Design. I also had this opportunity in the Department of Urban Planning, thanks to Mrs. Angela Filipeanu, in Landscape Design; together with Ioana Tudora, I worked there in the Department, but the prices of Bucharest and life in Bucharest...

- It's practically unbearable financially if you're not from there.

- What I earned at university, that's the truth - it wasn't enough for the rent. I worked at the same time for two years at Mol gas stations, in the investment department, where I learned a lot about the practical side of the construction site, i.e. who, how much and how loud they yell, and how they yell, so I could realize how big the problem is. But I had a friend who didn't want to stay in Bucharest - she had just finished university and really wanted to come back home - and at a certain point, however, there was a job as chief architect in Gheorgheni and that's how I ended up back home. It wasn't something so premeditated and decided on the spur of the moment. I think it would have been possible to live in Bucharest, as I was, young as I was, and how I saw culture and everything around me, but all these things together made me come back as chief architect. A short period, because I was young for that job. The problem is that university teaches you partially.

- It doesn't train you at all on the legislative side...

- No, but even if you go beyond administration, having an architectural office means training in knowledge and professional knowledge both theoretical and practical, but it also means communication, it also means knowledge of the business world; and at least in communication, for a chief architect, if he doesn't know how to communicate, it's a burden. I realized that, from the outside, I can do much more than from the inside, for a system in which decisions and proposals are obstructed by the fact that we are in a small town and everybody knows everybody, and the measures that should have been taken were not carried through. However, the fact that there was a strategy on monuments and listed buildings in the town and that support could be given for them was a very early measure, in '99-2000, and it did leave something to follow on from that work.

And then the girlfriend with whom I left Bucharest... we remained friends, but life changed, and afterwards, when I got married, I moved to Miercurea Ciuc, to the neighboring town of Gheorgheni, and we lived there for about eight years, until we came to the decision that it was best to return to Ciumani. Both my wife liked to ride, and the children - my daughter, too - and the most affordable option was to have a horse at home.

- How old were the children then?

- When I came home, she was starting school, so she was seven. During the summer and winter vacation we were in the village anyway. We had another little house somewhere in the Ghimes valley, we were there and there. But, little by little, somewhere in 2007, about eight years after I left Bucharest, it crystallized that I would live at home. Everything is familiar to me there. That's when this office was set up, because I saw that there were many good architectural offices in Miercurea Ciuc, only that each one worked individually or with two or three employees at most. And we had discussions with them: why don't we create a big firm, in which each one of us could participate with his own firm as a sub-contractor, but for big restoration works or works that mean a large volume of work, so that we don't miss the chance to be able to get the work done. It was the 90s, nobody was very trusting of each other, because on the one hand, the design institutes had sort of disbanded a few years before, and working together meant partly and, let's say, socialism.

- Yes, yes, there was a great reluctance to that kind of thing.

- There was, although they all admit that as long as they were there it wasn't bad. In Gheorgheni there was an office where we managed to do this, but not in the sense of: let's make a big company where everyone does his part through subcontracting, but then, in 2007, Larix was founded, where we started together. Then there were three of us, now it's grown.

- How many of you are in the company now?

- A total of 16 - that means it's not one firm. We didn't have engineers from the beginning; we worked with other engineers, but gradually young people from the area started practicing with us and they came to our office, became co-owners, and at some point when there was a chance for funding, they were young, and then they made a separate firm, and basically these 16 mean a cluster. There are 4 of them, there are 12 of us, but in these 12 there is also the joint administration, that is to say, they and we have the same secretary and so on. It is a model of coexistence where the engineering work for our work is done by them. The opportunity to work in the same space is a huge one, but of course they, with this number, have much more capacity than what we can offer them and so they also work for other firms in the area. This is not a competitive relationship, it's normal. So they also work for the outside, of course we also have our urban planning projects and together we are going towards the restoration specialization. We have many, many points in common and with the chance to use current design programs, working simultaneously, together and in the same model, and for each question the answer is at hand, there is an advantage that is also readable in terms of quality, but it also means efficiency.

- Let me ask you a question - I am not necessarily a great feminist - how many women work in your office?

- At the moment, three. We had another female trainee who is now on maternity leave, and fellow practicing engineers had a female student this year - she might get a job, but let's see.

- Four out of 12. Don't the Ciuc girls like architecture?

- I don't know... No, no...

- I am laughing a little bit, also because we had some very good students from Ciuc who graduated from "Spiru Haret", some of them in the same year as Vajk - Szigeti Vajk István, who worked in your office - and the girls had a much harder time finding work than the boys.

- We would have been happy for them to come. So, both girls, both internships that we have now, were trained by me or by colleagues in the office, and during the internship they always came back, more or less. That's a dilemma, because of course I could accept a lot more to the internship, that I have experienced colleagues who could take, but on the one hand, it's a huge effort to have an intern, because you need a computer, you need to be mentored...

- Right. Right. And you have to take the time, take the time to train.

- And what we're doing is a pretty special segment, which I don't know if it's available anywhere else in an area where timber is not as prevalent, so we prefer to hire an intern where we see that they're going to stay in the area. They don't necessarily have to stay in the shop, with an obligation to continue here, but stay in the region, because we are few compared to how many there should be, and then I prefer to retain a place. If you start a traineeship, that's two years, and if I don't see that it's the firm intention, then I don't know... I don't have time.

- It's an investment that produces nothing for the community.

- Yes, now, in Târgu Secuiesc there's an architect, Gál Zoltán, who worked for two years in our firm. He opened his office there, but now we are working together on the study of the historical center of Târgu Secuiesc and he is actually helping us a lot. I mean, the fact that he knows how we work in the office means that we can collaborate a lot and this collaboration is essential, and for this reason it is very difficult, if someone who is trained here goes to Cluj or elsewhere, in other areas, our time invested is lost...

- Well, it doesn't end up here; but on the other hand, the more people trained at such a school of internship spread everywhere, the better it is - for others, it's true.

- Yes, but I can tell them about workshops in Cluj, Bucharest or Timisoara that they can go to if they want. We now have two interns, one of whom is on maternity leave, but not many people want to come back. On the other hand, many of the architects who have finished have come back and they need manpower too. In theory, there would be absorption in the area, it's just that the economy here, in terms of salaries and so on, can't compare with what's on offer in the big cities. The university centers are still advantaged in that sense, because many people prefer to stay there because it's a different income level.

- Yes, sure, there are other salaries, but as you said, there are other costs of living...

- Yes, but that's what I don't see... the quality of leisure can be totally different. I mean, as much as I get annoyed in the office - it happens to me - if I go mushroom picking, it calms me down enormously.

And at the same time, this location outside the university centers is also a disadvantage in terms of architectural competitions. Because, in a competition, very many students can come to the aid of an architectural office. Of course there is remote work, but it's not the same.

- What is the first work that you felt you "scored" and are on the right track?

- The bell tower in the new cemetery in Ditrău. I remember that it was the Brașov, Covasna, Harghita Architecture Annual and I managed to print the plan very late, so it couldn't have been cachés at the firm, so I took the panel home to cachés it myself, because the printing ink hadn't dried yet. We had a corridor in the block apartment, a long corridor: on one side was the kitchen door, and opposite were the children's rooms.... and, lying on the floor, I was just kashashing the board with my wife, I was stretching out the sheet before kashing it, already greased with glue, and the middle boy had a bicycle, the plastic one you kicked, and he, in the corridor, saw a thing he could run over at full speed... This was the Saturday, I had no way to repaper, so the sticking appeared slightly watered... And I was saying to my wife: What a pity, she could have got a prize... She did, after all. That was the moment, but I don't think that's the main thing, the main thing is that Tövissi Zsolt won the Arhitext Prize and Mathé Zoli, in 2007, at the Biennale, won the President's Prize - it was Mr. Derer - with a work, the chapel of the cemetery in Remetea. Verbally, Mr. Derer also mentioned the Gheorgheni credit cooperative - it was my first restoration project. And this, the fact that they received an award, meant in the end that, in Romania, the countryside is somehow being appreciated and it may be a way... Practically, around that time they split up, because until then Tövissi and Mathé were working together. And Tövissi is a pole around which a lot of people circulated, who then started to make good quality architecture.

- It's extraordinarily important to have architects who are not just in it for their own self-promotion, but who want to mentor young people.

- Yes. András Alpár, Lőrincz Barna, Korodi, Szabolcs, Gergely Attila, etc., pretty much all around him, they all worked around him, they worked together.

This bell tower, with a built area of about 2.25 square meters, was the work we first succeeded with.

- Back to what you're doing now. Of course, all the Larix Studio works use wood, but they use it in a very specific way, in the sense that you don't focus at all on copying decorative motifs, and although it's a perfect implementation of the material, it's a technology that is accessible to, let's say, the average beneficiary, to small communities, to families with normal incomes. Why do you make this choice?

- On the one hand, we are in a region in which, beyond this image that people work with wood in the Secuime, there are very big differences between micro-regions, in the sense that ornaments and carved things can be made rather in hardwood, and this does not exist in our region, only in Odorhei, Miercurea Nirajului, etc. I mean, it existed long ago, while there were still oak trees, before they were replaced by fir trees - but somehow, somehow the traditional architecture in Gheorgheni, made of resinous trees, is based on rhythms, on the play of light and shadow rather than on fretwork and so on. On the other hand, if we go back to tradition, in the old days, people had time to do the details, today: what we have at hand, that's why we work and we would like to make these things simpler and simpler, because, of course, we did not invent that ornament is a crime.

- The theory has changed in the meantime.

- But we have discovered that everything that is negligible is not realized, and even if it is realized, once it gets to a state where it should be replaced, it is not replaced, it is discarded. So the architecture, somehow, has to be very simple and nothing has to be superfluous - and as we are working with a small budget, it is understandable that the labor also has to be very small. And in that sense we very quickly end up not being able to, so we have to do without ornaments, ornaments... So we have to go very, very to the essence.

- You have an extraordinarily wide range of work in this office, and things range from very beautiful restorations to memorials - like the Movila Tartars' Mound - and a lot of housing refurbishments. What I find impressive in the work of your office is that no work is treated as being too small or insignificant, and from this point of view, I was impressed by the Zetea bus station and the Ditrău stream bank improvement (which is not a small work, but it is related to the scale of the territory, the landscape, the locality). Tell me how do you treat these small works (which many architects would tend to ignore) as being in a very close relationship with the environment?

- The answer is quite simple. My colleagues and I are very much concerned with architecture, but all the same - understanding what architecture means, what the design process means, what the economics of it means, and well, we study the literature, from marketing to all the possible things... it's not an architect's job, but it is. Very quickly we realized that, in the initial phase, the project, the more people participate in the discussions, without drawing a line, the more specialists are caught who will work on that project, this means, on the one hand, a saving of resources - because it's not on the site that the problem comes to light, but at the design phase - but this team work leads to instantaneous deciphering of problems... and that's a big advantage. We have that round table, around which we're all equal partners, and those initial discussions basically very quickly outline a possible solution. From there it depends very much on the beneficiary how much they accept, it depends on the culture of the beneficiary, of course, but the fact that together we can very quickly decide the direction in which we can go, which gives a balance between possibilities and dreams, I think that's where these things are decided and that's where this thing comes from. Of course, in the case of some projects, models are made and there are variants, and this is also true along the way, that is, a work is not made and carried through to the end by one, but it's like chess: when two play chess, the good move is seen from the outside (and here you have the possibility to make the move, even from the outside) and the fact that engineers are also designers in a way and have a vision in this sense, helps us a lot. But also the fact that we also think structurally from the beginning (I told you about the course with Mr. Cișmigiu) is a situation that helps us.

- The structural part plays an important role, especially in the larger works, such as the Sânsimion maneuver, where there is an image that is very much related to the structural solution.

- Yes. The kindergarten in Lăzarea is also like that. And they understand and they don't say that it can't be done, but they come up with the solution as best as they can, but as economically as they can. Quality is possible when, from the beginning, everyone gives their opinion about the work, ideas are put together and a conclusion can be reached very quickly. Plus, there is this graph that I am talking about: if there are as many specialists as possible, the costs are reduced. And if they are not there from the start, as others get involved, then problems and additional costs arise in execution. So I drew this chart, the ideal project chart. It's just that if the person works in a team, and I've already encountered this problem, the difference in quality is noticeable, because there is the experience and there is the team.

- One of the valuable points of the architecture that you practice is the way in which you have succeeded in integrating into the landscape buildings that are not on the usual village scale, and here I am talking in particular about the manège. The manège is on a scale that is that of the surrounding nature, let's say, but in the case of the manège, the transparency that you have achieved, and which clearly has references in traditional saddle architecture, gives a quality to the architectural object that you rarely encounter.

- Of course, having this natural landscape. There are situations in which this recipe, that a large building can be broken up into several smaller volumes as large as the shed and thus fit into the village image, is a possible recipe, but sometimes... I am looking for a work... (images of the studio's work are scrolling on the presentation screen)... We have a work in the area of a skating rink and in a historic area, behind it appears the fortified church of Cârța. Here is the site where we intervened... so, basically, there's not much of an overview. You can see here. That's the fragmentation, but from the other side, and that reaches the village scale. Somehow the site and the relationship to the neighborhoods are always fundamental. That's how it appears. A big volume masking an even bigger volume. But going back to the need to have a dialog with the context, this is an ongoing concern. However large the proposed construction, it must say hello to its neighbors. I mean, the Titanic can't park in the fishermen's harbor, it's a different scale. And then, it needs to be seen, because if it comes to the conclusion that the harbor needs to be deepened, the fishermen have no business there, but maybe there are solutions. Just as that bus stop was given a surface of draniță, because a local saying goes that the people of Zetea were made of dust by God, but live on wood. And then they should be used to that surface, and the young people. Where? At the bus stop. Break into smaller volumes if you can... if not, then transparency or how the landscape appears between buildings. There is no recipe, there is only an understanding of the context and the real truth is that at the moment, when we have the possibility to see from above, with the drone, it is much easier to make an insertion in this sense. Most eloquent is the situation with the Lăzarea kindergarten, where we had three category A monuments in the protection area and three trees. But also in Lăzarea there is an older work, the sports hall, which is contemporary with the Năstase halls, except that here the community said that they did not want this metal hall in the monuments area.

- It was an astonishing thing, that metal hall, implanted everywhere...

- They said, if they get the funding to do it, they'll put in the surplus to have a real hall. And now that hall is also an event center and a gym, but from the hillside it has a green roof area. Basically, from above, it's less present in the village image, half of the building is masked by the green roof and, on the other hand, being in the monuments area, by reflex, one is tempted to put titanium-zinc sheeting on the roof. It's just that, here, we have chosen that horrible pitted green sheeting, which from the point of view of these reflections you wonder what it's doing there, but precisely because of it, here, it loses the building even more in the context of the landscape. Well, when it rains and the sun comes out after the rain, it shines. This is a situation that cannot be solved, but the fact that sometimes we have to go beyond what is agreed and beyond the templates is certain, because it is impossible otherwise. We are not forcing the issue but, when necessary, we must see what can be achieved. It is clear that this goes beyond the usual canons of intervention in a monument area, but here it must be recognized that it is not only the monuments themselves that are of value, but the landscape value of the site is much greater than that of the monuments and then the relationship is made to the landscape.

- Let's go back to a slightly smaller scale, to housing, which is actually one of the main subjects of architecture. You have done a lot of rehabilitation of rural houses and you have made your own house by remodeling and very small extension of your grandparents' house, but you have also done a typical project of a Secessionist house: a relatively modest house, with simple techniques of putting it in place and you write on the Facebook page of the firm that it has been about 10 years since the project was first realized. Why do you think that happened?

- The fact that we're in the business of rehabilitating old houses and extensions is because the area, economically, is not a very, very prosperous area.

- That has helped a lot in keeping the character...

- And then people came with requests along the lines of: this house, is there anything else I can do to it so that I can live in it? Basically, we worked continuously in rural areas with rehabilitation and upcycling solutions during the period when there was money for new housing in Romania. And that, in a way, has meant not that we are very good or that we are better than the others, just that we have been doing it for longer and we have an advantage in that sense... that at the moment when Romania is rediscovering the countryside, these small works can be the answers to the problem.

- If there's more to discover... I'm very pessimistic about that.

- Since 2010 I have been doing village inventories with some architects, at first on my own, then funded by the Dutch Embassy, for the Pogány-Havas micro-region, on the initiative of a micro-region manager, Rodics Gergő, who came from Hungary and noticed the values here. With Tövissi Zsolt, Bogos Ernő, and after, with Esztány Győző.

- In a way, although it's poor, the Secuimea has this advantage that it can "suck from two sheep".

- Yes. And poverty preserved the buildings. And then we ended up that, through lobbying, the Harghita County Council had this program of inventorying Harghita's villages, which was started with very great impetus, it was very beneficial, only it was discovered that in the four-year political cycle, such a research - inventorying, which should last for decades until we finish, is not usable as an electoral argument further on, or not to the efficiency in other areas of investment. So, we then came to the conclusion with the village inventory that if there were to be new constructions in the countryside, they should take into account the image of the village. We have a saying that several geese in one place are as big as a pig, and traditionally we do not have spectacular houses, but if we have geese in the village, we should not put pigs next to them, and this is the idea behind the program of the Secler house, within the program financed by the Harghita County Council. They also have a very interesting program, thanks to this lobby of architects that we have managed to create: they have a program dedicated to historical monuments, which can be inventoried, the necessary studies can be carried out, the necessary surveys can be done, the expertise can be done, the design can be done and they also co-finance the restoration. So, the idea of this house in the countryside, basically what you see today, is due to this program of the County Council, financed from the village inventory program. It is not a program invented by the Council, because the Council also took over the Pogány-Havas micro-region program, which we talked about earlier. So, somewhere around 2006-2007, with the awards won by Tövissi Zsolt and Mathé Zoli, we started to be concerned that there are craftsmen, carpenters in the area, there are small companies making wooden houses for export, there are also award-winning architects in the area, but the cumulation is not visible in the image of the villages, and if there should be a need for new housing in the countryside, as service housing for doctors, teachers, vets or those who settle in the countryside, then they should be a contemporary continuation of the architecture that is there, that fits into the village area. In this way nine prototypes have emerged. Actually, it's a longer story. It was a kind of popular school where, with architects from the area...

- The one on the banks of the Mures.

- Yes, yes. So the whole story was concocted there in two rounds. The first two rounds were with a lot of ideologies and from the area of organic architecture in Hungary, Makovecz and others, and what basically resulted were these nine model houses, which were realized at the level of the feasibility study. Things got a bit bogged down here; it didn't proceed in the sense that there was miscommunication. We have said that it is worth having these model projects per region, because a good project can save five or six times the cost of the design, and if it becomes a prototype, it can be improved over time and then it can be very effective.

- I'm asking about this house, because in the late '80s, the architect Călin Hoinărescu made an extraordinary catalog with inventories by regions, prototypes, and nothing came out of it...

- Yes, it was precisely then that Zakariás Attila Zakariás Attila made the surveys of the Covasna area, under the pretext that they would be used for studies. But this communication: how much does a project cost? - Well, come on, about 2,000 euros... Well, if they can save five or six times as much, then the politicians quickly came up with: look, with the Saxon house you can save 10,000 euros; the projects are ready! The projects were not ready. They were ready at feasibility study level and they didn't say they had communicated something wrong... Things somehow got stuck, but people were coming, they were interested in the projects, which were already on the Council's website. Until we had the project ready for construction and until someone really decided to do something about it, this period of ten years went by, during which we, in the meantime, came to the conclusion that , given the number of abandoned and uninhabited houses, it is better not to build new ones, but to rehabilitate the old ones. But still, even if a new house is realized in the context of the village image, which is still coherent, then these typical projects could be a solution and that is what is being built in Remetea. There was a discussion between us, that we are usually very present on the construction site and we keep the realization very close, but in the construction site it is modified, it is not done exactly as in the project. But, overall, I think that if many of these houses were built instead of others, even with small compromises, it would be much better than what is happening now, because the quality of architecture in an area is determined by the average, not by the peaks.

- Absolutely, it is, and the average is disastrous. Fortunately not here, nor do I know what the explanation is. After all part of the explanation, as you said, is in some poverty. Just out of curiosity, I would like to ask you a question: don't people go abroad from here?

- Yes, they do, but the wave was earlier, it preceded the general phenomenon in Romania. So, before the Italian and Spanish "căpșunarii", those who wanted to leave here went to Hungary, when the borders were opened, in a way similar to the Saxons. The trauma is starting to be processed somehow and there are many who are coming back.

- Anyway, the influence was much closer. I was thinking now that it's a problem in many parts of Eastern Europe and beyond; I remember meeting a Turkish-Cypriot architect at an architecture conference more than 10 years ago who was doing a research paper on exactly this: "Coming home" - how what the world has seen abroad influences village architecture. No one seems to escape this phenomenon. For example, the catastrophe at Certeze, which has become a subject of study for sociologists, is hard to explain, although the phenomenon has been going on for a long time with the huge, practically unused, one-story houses (built since the 1970s), when the family lived in old houses in the backyard or in the kitchen and in one room of the big house. Is there a remedy for such things?

- The remedy is that most of those big houses that were built (they exist in our country too), to show that they didn't go to Hungary for nothing, are of such poor quality that they will very quickly deteriorate and disappear. This will take patience, another 20 years.

- You are optimistic! So be it!

- Plus they can't be heated and so on....

- What I think is great about the housing rehabilitated by your office is that it's part of a juste milieu, a good means of intervention, it's not excessive in any way. I've been looking at the latest Annuals, and Biennales, and what else is being built in the countryside, and there are two extremes: one is an architecture practiced by a few architects, an architecture after some perfectly copied historical models that really no man living in the countryside can afford - these are for people with money, coming from the city to make a fuss somewhere in a commune - and there is the other end, where people like Lorin Niculae do very good work for very poor communities, with a very low-tech architecture. That seems to me to solve some things, but it also condemns the countryside to perpetual poverty. Perhaps local administrations should be given more means to manage these phenomena. How does it happen here? What is your relationship with the authorities?

- It's a good question because, on the one hand, when we work on an urban development plan, they often don't understand why they need a finalized strategy before they start on the urban development plan. I mean, they don't understand that there is a development framework in the urban plan, but if there is no development vision, then you can't do the proper framework. On the other hand, the fact that there are no chief architects, I mean, the institution of the chief architect is as it is, I mean, even that veto right didn't exist in what it was in the 90s... that on esthetic grounds the chief architect can refuse a work that doesn't conform, has led to the fact that a lot of design firms...

- Unfortunately, the signatures belong to the architects and this is a big problem...

- Yes, yes. They work with public administrations, where the award criterion is minimum price. So, from this point of view, we have a fairly narrow field in which we can move, because often the tender documents are not even fully scrutinized by the bidders and those who do scrutinize them end up at a disadvantage, because they specify solutions which, if they are respected, do not result in the same price. A typical example I can give: if we specify titanium-zinc for the cladding, the execution price is clearly not the same as for galvanized sheet, and the same is true for the design tender. So the person who does not see all the nuances and all the complexity of a tender has no way of correlating the tender with the real content. This is a difficult area with the administration because... this is the situation. So the chief architects comply, or not, with what is stipulated in the urban planning documentation, the projects are put out to tender, where the minimum price is the deciding factor. The complexity of the projects means that they often cannot be done at the price that is the threshold for direct purchase. So, on the one hand, working with the authorities is interesting because usually the architect has more freedom of movement, but it often becomes unprofitable due to public procurement. And with a private dwelling there is the moment when the wife shows up. It's good to be the first moment and things are discussed in detail. From this point of view, there's a chance that, from a creative point of view, people will have a freer hand when it comes to public investments. On the other hand, public works are analyzed in this bureaucratic system, which does not favor fair works, but favors cheap works. I think this can be seen in the architecture of the country's public institutions.

- All we can do is hope that the authorities will give in....

- If only they would raise this threshold...

- If only price wasn't the only selection criteria....

- But they're limited too. I mean, at the moment, for design, this threshold at which they don't have to tender is 27,000 euros. If I have a monument for which I have to carry out the necessary studies, with the detailed survey, which is absolutely necessary, and the archaeology, the biological study, the study of the artistic components, the archive, the historical study, the technical expertise, the dendro-chronology and so on... that's all over with. Where does that leave my design area? That's the sad situation. But there are authorities we work with. Lăzarea, Ciumani are areas where we have projects.

- You have good contacts with the authorities.

- Yes, yes, long-standing relations, but even in these cases we have not been able to consistently do the work for which they contacted us, because there were also cases where, although we did the SF, at PT we lost the tender because they came up with a dumping price, very low, it was clear that it could not be done; they came up with deadlines that it was clear that they could not be met, but they find the artifices to justify at the tender stage - and then not keep their word.

- And in this way, many construction and architectural firms bid on prices and deadlines which, in the course of execution, go somewhere else entirely.

- And the criterion of being present on site immediately after solicitation was solved on one job, where it was really necessary: the bidder's response to clarification was: "a worker of mine lives opposite". Well, at least an engineer, not a laborer, should go on the site, but things are causing public investments, which could be an engine of development and examples for people and the community, to stagnate in a lamentable area, where firms that are plumbers and find an architect with a signature, to dominate the market.

- On the other hand, some investments are being made that are at least partly public... I had here a list of realizations that actually terrified me and which are super, super-admired, in areas where wood is worked. There are two church complexes in Maramureș. One is the monastery, the new Bârsana Monastery, which has overshadowed the historic monument - all the tourists are flocking to the new ensemble - and the other is the Peri Monastery near Săpânța. Both are on impossible scales, with colossal carvings, magnified architectural objects, simply two or three-storey cellars... How can these aberrations be stopped?

- The chief architect doesn't want confrontation in such small communities, plus he's often not even an architect. I mean, that's not a very desirable profession. On the other hand, it is not only the chief architect who is to blame, it is also the architect who signs, it is also the lack of culture. Basically, the phenomenon is not necessarily new, because in northern Transylvania, after the Vienna Edict (according to Romanian terminology), the Hungarians call it the Arbitration of Vienna - I am not a historian to discuss it, but I want to say that things look somewhat different, often from different angles - there have been investments from the government in Budapest since then. Very big investments, even though it was during the war, public investments. And the architect Kós Károly dissociates himself from them, in the sense that he says that these investments are too Secessionist: with big roofs with big sloping roofs, with carved pillars and so on .....

- We are entering a very interesting field of architectural propaganda.

- And he says that things should be looked for somewhere else, because it's not the form that counts, but the spirit: "the Szekler remains a Szekler even if he dresses in a jacket and a top hat, but the foreigner does not become a Szekler even if he dresses in the local costume". This problem existed and still exists today, without being productive... The phenomenon can't be denied, that's very clear; how it can be handled is a problem. With us, it was solved quite simply. The reduced financial possibilities have stopped some of these colossal interventions, but not everywhere and in all cases.

- We have a tendency to focus only on legislation and architectural education and the very good materials that the Order, the Union have produced: the best practice guides, there was a group for rural people at the Order - these are excellent things, but they are aimed at the specialist. There is clearly a problem of visual and architectural education of the general population. As you said in a presentation of the kindergarten in Ciumani: visual education starts in kindergarten - but in our country, this part of visual education is phenomenally neglected, it is only for those who go to art high school or architecture high school... For the rest, things are a bit salty and there are no quality publications that are not specialized. I remember that in the 80s, when I was working in Satu Mare, there were a lot of Hungarian magazines, of very good quality, which were not architecture magazines, they were popularization magazines....

- Szép házak (Beautiful Houses), Kész Házak (Ready-made Houses).

- Exactly, these and Lakáskultúra (Housing Culture). These magazines still don't really exist in our country; that is to say, there are a number of publications that popularize a kind of sinister kitsch, and there are the big magazines, of course - Zeppelin, Igloo, Arhitectura - but they are aimed at a very narrow target.

- It's a difficult subject, because architecture, after all, starts from the commission, so if the recipients are sufficiently cultured or smart enough to understand that quality architecture means much more than functionality and appearance, then you can do architecture like Péterffy Miklós with the houses he makes... the Nădășan house. The Biennale showed how he can take the modernist tradition in Cluj, taken to its essence, and make that very beautiful house, the PJ villa.

If we say that visual education starts in kindergarten and in kindergarten the product that appears there is the product that has been judged on the "cheapest" criterion, it is hard to talk about an architectural culture; because I don't know why people think that kindergarten must be very colorful, with lots of colors, and the furniture in kindergarten must be curved, with wavy lines, etc. Now explain to me: a child who grew up in this environment, where all the colors were all around him and all the possible curved lines appeared in his surroundings and this was the model - this is the kindergarten - how can he understand that modernist architecture with all its contributions - with the horizontal window and the simple, white volumes - can be beautiful? In a way, of course, the rounding of the corner in kindergarten furniture has an explanation, but it should not become the most important criterion in the whole design of a kindergarten. And we can move on to school. How many hours of education do they have in the sense of architecture or environment? So we understand that those who graduate from an architecture high school have the background, even if they become a primary school, they can understand this. Except there is a danger here too... after four years of high school, some may think they are great architects... and it happens.

- But there's something else. I told you that not all architecture schools are equal. Of the students I have had, most of those who went to the high school of architecture in Miercurea Ciuc have had very good results, but there are also high schools of architecture that are catastrophic - I don't want to name them - but they teach students a kind of mannerisms that they can't really debate and that don't really help them any further, instead they are totally deficient in general culture. Here things depend solely on the quality of the teachers.

- It's very sad that this is the case, but the sources of information are different today; everyone can comment on Facebook... In the old days, when a specialist was invited on TV and said something and people only watched TV, the profession had a much greater impact. Coming back to education, the average architecture educates people and their taste, not the peaks, and we are doing very badly here.

- On average we are catastrophic.

- These are the areas where we have a lot, a lot, a lot to catch up, because at that point there really will be a clientele that can behave as patrons. Not in the sense of throwing money on the table and saying "do what you want to me", but still understanding that, professionally, giving the architect a free hand is a win-win for him as well. Until the man realizes that, as Loos said, "the street is the living room of the community" and when he puts a house there, he is basically putting a piece of furniture in that living room, and if it doesn't fit, that living room can't be used and with one intervention he can destroy the image of a street for 50-60 years. That's a problem with post-1990s "democracy": What, I can't do what I want on my own land? The question is: whose facade is it? Does it belong to the house, to the owner, or does it belong to the community? Of course it's the community's...

- But the owner before he knows...

- That's a problem. It's also a problem that the status of the man, that he's a rich man, must be displayed and necessarily respected by the new construction and that it must be different from everybody else's - because this individuality is now being raised on the post - and all these things cumulated lead to the discrepancies that make us sad. I can make a good house, but if that's the only honest house on a street and the rest are different, that's not going to be normality, normality is going to be the rest of the 90 houses.

- Yes, the situation is indeed pathetic; between a few extraordinary works, most of it is downright sad, and that is why what your architectural office is doing is remarkable. A phrase written by Peter Zumthor comes to mind: "Some buildings give the impression of being an obvious part of their surroundings and seem to say I am as you see me and I belong here". This concern to make architecture that belongs to this place characterizes you. Was it easier to work at home, in Ciumani?

- I will say that I have nine projects for that house (my own house in Ciumani). It's a special situation because - it was built by my uncle, but it was eventually lived in by my grandparents after my uncle sold - it's basically a move into the countryside. As opposed to the usual cadence of houses, it was interposed between two houses, thus reducing the distance between them. The problem arose in the following way: if we lengthened the house - we took the view from our parents' kitchen. The country kitchen is the basic place; if I raised the house very much, I was taking the light, so it compromised the sunshine of the parental house. If it was at the normal cadence, as it would have been, getting up a bit was not a problem, maybe only for the image of the village, but otherwise... And then, a transposition of a knot that is found in Gothic, or Gothic style, so to speak, because in the Baroque, Gothic was preferred here, namely: if the rafters rest on the chord and are well fixed there, with all the insulation and all the supporting layers, they become sufficiently rigid... With the rethinking of a Gothic-style knot and the use of bolts, in which some triangles became stiff enough that I could live in the attic, led to this final solution where the middle of the house is raised so that the sun can get in upstairs as well, other than through attic windows. In practice, innovation often means a slightly different solution. This would allow the communities here to make fair use of the houses, in the sense that in old age no one will go upstairs because, however comfortable the staircase may be, it is still a staircase.

- Doctors say it keeps you fit.

- Yes, they won't have the money for the elevator, but anyway, if you live in the village, it keeps you in shape to work in the orchard, in the garden.

- That's plenty of exercise.

- Basically, the current state of our houses would allow life in old age to be spent on the ground floor, as normal. And, for example, this innovation means that, without having to change the roofs very much, it can become an expansion space for the period when there are children, and then, while there are children in the whole house, including the attic converted into a loft, it can also be used in old age, life can be restricted to the ground floor, and then to the kitchen, so to speak - that is where people traditionally sleep. I exaggerated with the kitchen, but of course two rooms are big enough for heating. And in this way the lesson from school, that the door of the shower room is enough to be 70 centimeters, needs to be slightly modified, because perhaps in old age the wheelchair user will not be able to manage in 70 centimeters,

People hold on to their property because for them the house is either their grandparents' or their own, so they don't change it as easily as they would a block of flats.

- Plus, in the countryside, in many households, there is still this dialog between the big house and the small house where the old people move to...

- Yes, but you don't leave the tree you planted, so that's where you want to live, and in that case the house has to be thought of in different stages. Even if I have a big family that needs a big house, then we have to see how it will work when the children leave, or when they come back with the grandchildren, or temporarily when they come back that they want to live here, if it comes to that, so somehow we have to find this balance and this scenario that this house, even in the extended version of living, does not go out of the image of the traditional village, or at least traditional. Because of that the project has had many rethinkings and rethinkings, but this work has not stopped even today. Traditional stuff like: look we have three children and let's have three children's rooms. Why have three rooms for three children if you want that child to lead a community life and be part of the community? Well, if I give the child that room and put a baby-phone in there, I'm encouraging them to be on their own. But actually, the children wanted to stay with us. Then, when they get older and everyone needs their own room, then yes. I've moved into the living room now and that's where they sleep.

- And the boys have a room.

- The boys have their room, the girl her room (former and future master bedroom), but I sleep in the living room, although I could sleep in the room with the fireplace as an option. But that will change again, because that's the nature of things. Now, when the house is almost finished and there's nothing more I can do to it - some electricity bills come in that have got me thinking. So, I've got a shingled house, part tin - this roof on which we have solar collectors for hot water, but now, seriously, I'm thinking I should put photovoltaic panels. I didn't want to put on this house, but here's when I'm seriously thinking about what it would mean. There's a situation now, a context... How long will this context last? When will we return to normality? - I can't give the answer, but it's pushing me more and more towards an autonomous dwelling in many ways, so energy autonomous. With photovoltaic panels on the roof.

- Of course that autonomy is part of a range of traditional housing. I remember about 10 years ago, so-called zero energy housing was all the rage. But there were some terrible solutions where the house had a structure with aluminum profiles, with all kinds of super-insulating materials; the idea was never to open the window, because you'd lose heat......

- Of course, things are different in the countryside and with the current built environment, I believe that low-energy housing can be realized; because even traditional houses were designed in a certain way and can be taken further with insulation and so on... But to become a passive house, that I doubt it, but the energy contribution of collectors or photovoltaics can still be taken into account somehow. I think we'll get there, come what may. But I also have to get used to the idea, because I have photovoltaic panels... so I still have to chew the cud. After all, any green architecture in the village starts from clear-headed peasant thinking.

- We're moving into modernity, but ....

- I can't be in a hurry, because I have the financial aspect. It's a reality in this country.

- It is, and if you say that it's a financial problem that concerns you, can you imagine how much it concerns your neighbors, who have a different level of income.

- People now see one thing. They put photovoltaics on the roof and the electricity practically goes into the national grid. I'm in Gheorgheni, the 220 kilovolt line runs through here, at the end of which is the Bicaz hydroelectric power station. Here, there will be no voltage variations, so the transformers that transform this 220 kilovolts to 110 and to the consumption that the population needs are in Gheorgheni, so the network will be charged very quickly. At some point, when there is too much current, the grid is no longer stable and then the inverters will not let the energy produced feed the grid. It's no use having photovoltaics on the roof, they won't let me feed into the grid... And here's the problem that so far the 5-6 kilovolts I need cost somewhere between 30.000-35.000 lei. A house with a hybrid system requires you to put in batteries, that costs enormously, so a system has to be adopted that allows further development of the hybrid system. This is the heart of the matter. We have this problem in the office too, because we heat with gas, and what will it be? Last year we were assigned to a different supplier, who was in no hurry to bill, but even when he did bill - for one month we were paying 20-something thousand. Well, out of that, if we'd put one more in, we could have built a photovoltaic system. But the office is in the historical center of Gheorgheni. The issue of historical monuments in this context again raises serious questions...

I think without realizing it, in 2008, I designed our house, which in the context of that time was not a big house.... but by today it's become a very big house in terms of energy sustainability, even though it's actually a normal low-energy house.

- It's a normal house, but it's also a question of volume.

- If we are talking about education and the image of settlements, now this energy aspect: those who live in historic monuments have a problem, to live in a historic monument, but I am not allowed to insulate, or I can do compensatory insulation. I'm not allowed to put... so what do photovoltaics look like on a monument? When can I, when can I not? I am supporting something that is part of the cultural heritage, I'm making efforts to keep it standing, on the other hand, I have enormous costs compared to the rest of the world. The situation will probably lead to the abandonment of monuments, in many cases, the owners feeling that they are being abandoned by the state, they only have obligations, restrictions.

- That's what it is. Unfortunately, at the moment, to live in a historical monument, to be an owner of a historical monument is a phenomenal nuisance.

- So now, how this energy issue will affect things is a very serious question. But if we're also talking about urban planning, this year's drought is a sobering thought. Wouldn't landscape architects also have a say in urban planning?

- I've seen some solutions this year, as if in a park in Iași, with succulents and cacti, stones on the ground, because they don't need to be watered, which have kind of terrified me.

- Coming back to the house, it heats with less wood than a traditional house of similar size, it's well insulated, but with the life we lead there are times when we consume a lot of energy. In the summer I have no problems, I have just enough hot water - from the collector. In the winter, when I heat, I have enough hot water, but in the fall and spring, when the house is well insulated and doesn't need to be heated, the collectors can't cope with the amount of water that is consumed. I have three teenagers, each of them wants to bathe in the evening, and when I leave in the morning to take a shower, I can only heat the water with electricity. I think that country living, for those who are now moving from the city - and there are more and more of them - is still being experimented with.

- There are, and this contributes in other areas to the preservation of local architecture, but I would like to see more and more offices like yours, which contribute to passing on tradition with minimal and contemporary means.

- It's clear that at the basis of any green architecture is the fresh mind of the peasant, so that's where we need to go back.

- We can only hope that things will evolve in this direction and that examples like your office will be followed by more and more young people returning home.

- That would be great, but now IT is taking over.

- Yes, but IT too, you know how it is, you can work on a computer from Ciumani.

- A lot of people are coming back and it's a segment that has discovered that they can work remotely. The physical presence can be solved, it's not a problem at salary level. That living somewhere in the country, where it's closer to healthy food sources and the environment, is starting to be an option.

- Here's the hope.

- Ilnca Păun-Constantinescu's Shrinking cities captures this phenomenon of moving from the city to the countryside. Here in the countryside there are fewer and fewer of us, and that's where people have left.

- In Ciumani there's a kindergarten built in 1928.

- Yes, a little.

- There is propaganda, and often architects willingly or unwillingly become the bearers of this propaganda. I confess to you that the main reason I like your architecture is that it is anti nostalgic and anti propaganda, but for that you have to be sufficiently relaxed and local.