Heritage recovery and identity interpretation

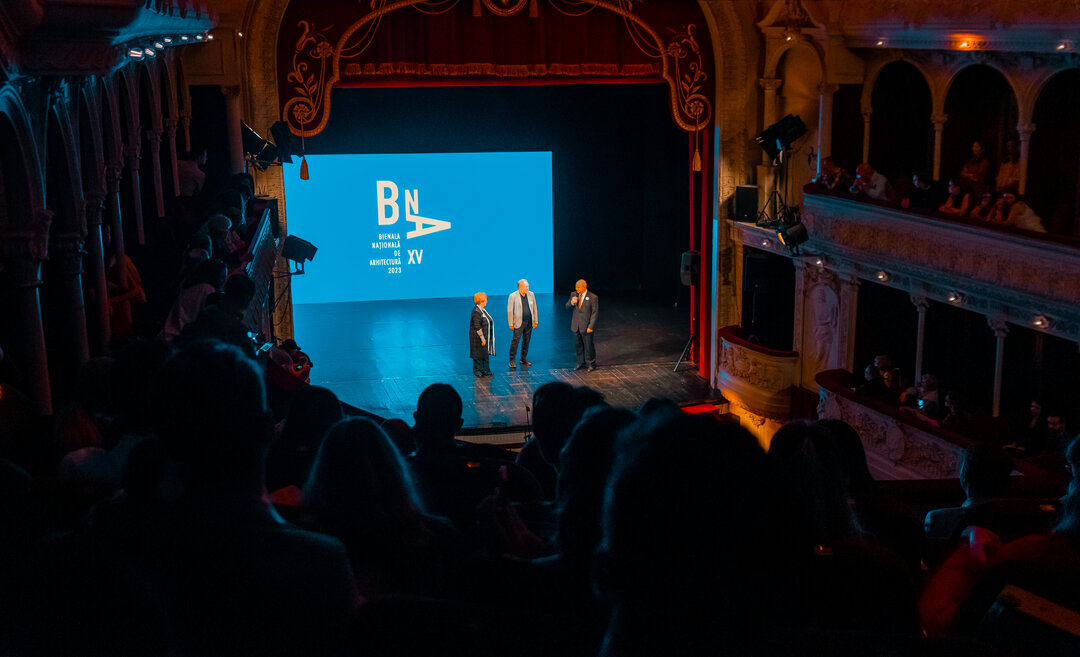

The experience of the jury of the projects dedicated to the immovable heritage entered in the National Biennale of Architecture - BNA 2023 gave us the opportunity, beyond the participation in the selection process and the recognition of professional quality, to confront ourselves with a picture - obviously incomplete, but nevertheless panoramic and relevant - of this segment of professional practice: the restoration and/or enhancement of valuable historical buildings. Several aspects emerge clearly from this confrontation which we can highlight here and which we know, in various forms, from every contact with the cultural heritage protection sector.

I would start by noting the frequency with which we are confronted with a simplified practice, in which decisions seem to become stereotypical, applied without sufficient understanding of their impact and - very probably - without sufficient prior knowledge of the buildings subject to intervention and their values: All too often we come across mechanistically applied, unfortunate, one-size-fits-all solutions, such as removing in extenso - plaster, carpentry, frames, floors and other defining historic building components - and replacing them with less or not so appropriate solutions, starting with reinforced concrete floors and continuing with carpentry made of other materials and of other than historic proportions. The discussion can continue - and should continue, properly developed, but not here - because we are witnessing a trivialization of inappropriate practices, leading to a change of perception towards the historic environment and a loss of landmarks in the protection of built heritage.

It must also be said that the state of decay - sometimes extensive destruction - from which some projects start does not leave many options for preserving authentic aspects. They end up with forms of reconstitution or even hypothetical reconstruction, in an attempt to recover not only the functionality but also the symbolic role and prestige of a monument on the brink of extinction. It is, unfortunately, another peculiarity of recent decades - the vandalization and destruction of historical monuments (yes, even those protected by law), in plain sight and without any restraint. What to do in such cases? Here is another topic for discussion.

I would add to these observations the lack of a minimum theoretical framework for many interventions, evident from the contradictory decisions found in one and the same project, but also from the invasive interventions of the category mentioned above, which go against the generally accepted principles of restoration, as they are based on European theory in the field, as described in books, conventions and international documents and recognized, at least declaratively, in Romania: I mention only the principle of minimum intervention and that of compatibility. Reversibility is often out of the question.

However, the portrait sketched here, which is obviously simplifying, has many causes - starting with architectural education and insufficient or inadequate specialized training in restoration for architects, engineers and other professionals in the field, continuing with the precarious institutional and administrative system for protecting cultural heritage, which has been consci conscientiously dismantled by almost every government over the last three decades and has become purely bureaucratic and disconnected from the reality on the ground, then continuing with a construction industry that is largely lacking in the restoration sector, from the production of materials and the provision of services to the specialization of construction companies, continuing with public procurement with irrelevant criteria and, increasingly often, wrapped up in the inappropriate Design and Build formula, then with precarious and inconsistent funding systems, oscillating from lack of funds (e.g. PNR) to abundant funding in impossible timeframes (e.g. PNRR) and culminating with the lack of clear and applicable quality criteria throughout the entire duration of an intervention.

This state of affairs is not specific to Romania, although it has its own particular characteristics. However, the situation is known and recognized by the European Union, for example, through documents such as the special report of the European Court of Auditors dedicated to investments in cultural heritage, diplomatically entitled EU investments in cultural sites: a topic that deserves more focus and coordination (2020), which shows that there is no appropriate framework to ensure the effectiveness and sustainability of interventions on cultural heritage and that investments are approached instrumentally, as a means of promoting economic objectives, which leads to missing the main objective, which is to protect cultural heritage. A way forward is indicated in a document produced by a working group coordinated by ICOMOS with a mandate from the European Commission in the context of the European Year of Cultural Heritage 2018, entitled European Quality Principles for EU-funded Interventions with Potential Impact upon Cultural Heritage (2019, 2020), which indicates the problems and proposes solutions for the whole pathway of cultural heritage investments. These documents are still little known and far from being applied in Romania.

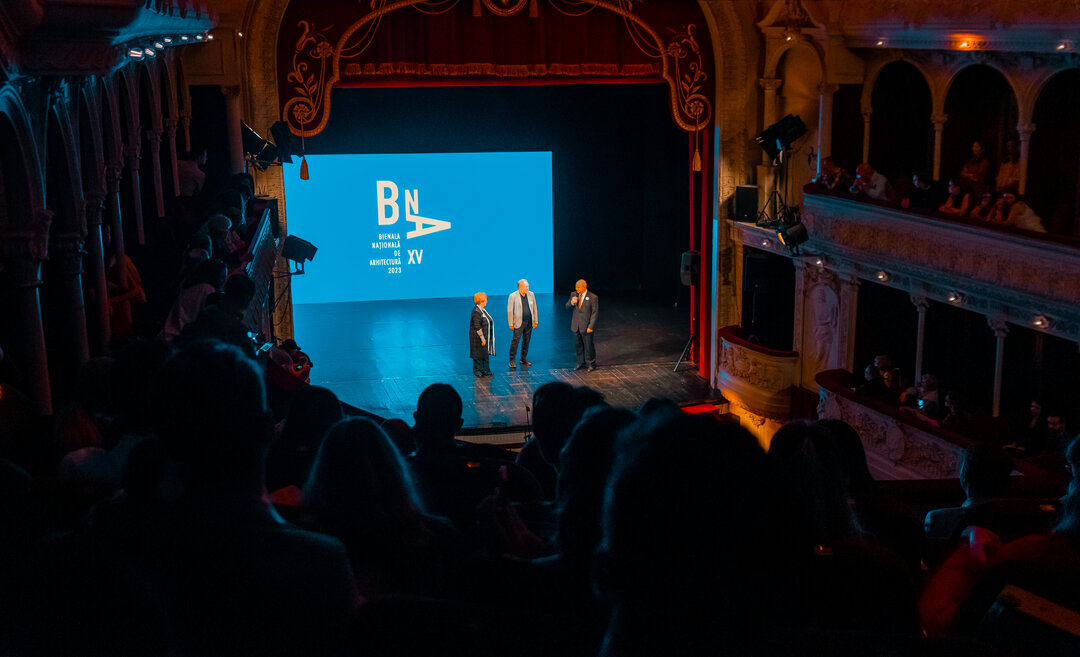

An exhibition like the BNA can be seen in many keys, but we cannot bypass this key, that of projecting against the general background of the cultural heritage field, which allows us to follow its evolution and recognize its achievements.

The projects presented in the competition are relatively numerous - more than in other editions and other annual or biennial architecture exhibitions - but still not as many as we would like and as many as we should, if we consider the European and national funds allocated in recent years to this sector. We are pleased to note the large number of quality projects, just as we are pleased to note their diversity - projects of different scales, different degrees of complexity, different orientations. However, all the projects presented in the NAB inevitably suffer, to varying degrees, from the problems listed briefly above and should be understood as such, and the nominated and awarded projects should be all the more appreciated. These are valuable projects, each in their own way, as we have tried to show in the succinct comments accompanying each nomination and award. It should be noted that most of these projects are due to young design teams associated with experienced professionals, indicating a generational change and a greater interest that the cultural heritage protection segment of professional practice is arousing in young architects, which is gratifying.

I conclude with a general appreciation for all the projects presented, for the efforts of their authors and those who made them possible - we all know how difficult it is to carry out a restoration project in the current context in Romania.