Public space/community space, two concepts in one event

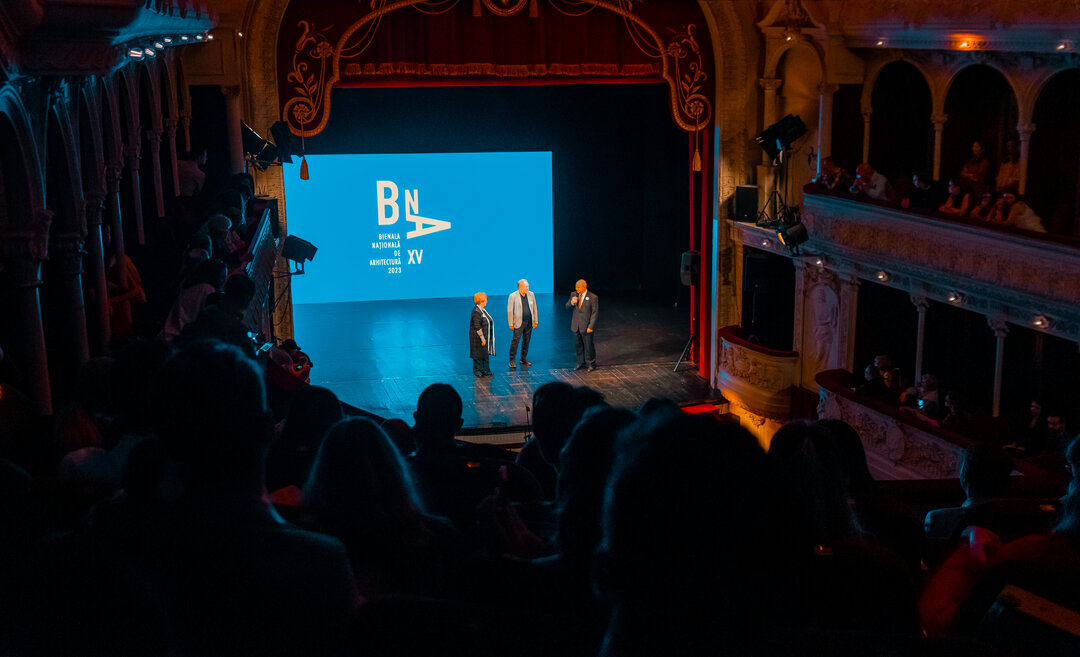

Far from being an event dedicated solely to the architects' guild, the National Biennale of Architecture is a means of promoting values and also of educating the general public in a wide-ranging field with implications for every moment of everyday life. Nothing new so far, just a repetitive wish, in the hope that civil society's response will improve and we will see the good things that are being done, not just the more or less questionable interventions that are the subject of spectacular media exposés by sensation and audience seekers.

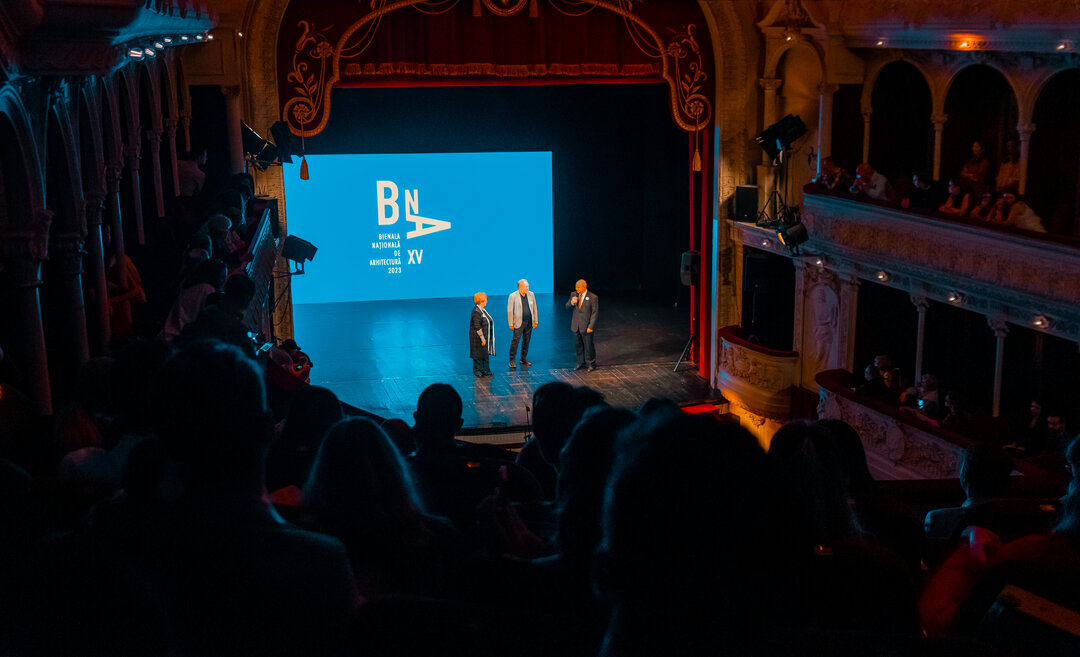

With slight initial reluctance when I was asked to manage as curator the Public and Community Space section of the BNA 2023 edition, reluctance due to a generally low participation of projects in the section, especially amid neglect of the subject by local authorities, I eventually found both the formal resources and the support of the UAR in slightly changing the rules of the game so that the section dedicated to public space would enjoy the widest possible participation. Thus, in addition to the projects that participated in the judging session and were entered in the competition for the section's prize winners, we gave the participants in the architectural competitions organized for public space planning the opportunity to present their work in an exhibition that would appeal to the general public and professionals in the field, as well as to local authorities, once again highlighting the undeniable benefits of organizing architectural competitions. The participation and prompt response of fellow architects was remarkable, for which I thank them all for their efforts.

Based on the idea of Adolf Loos who said, at the beginning of the 20th century, that the role of architecture isto arouse people's emotions, do we find this feeling in contemporary public spaces? It seems so. The projects entered in this year's National Biennale of Architecture in the Public and Community Spaces section, whether prize-winning or not, along with all the other projects entered in the hors concours section, are living proof of this. The jury had the difficult task of trying to separate not just projects, but ideas, subliminal messages, sensations and feelings hidden between the lines. I found among the projects a mill, with all the symbolic and semantic charge of the term, located in a Garden between the blocks (section prize), a horad (hejsza) of the roofs of the sheds - a sculpture frozen in the market of traditional products, a paradise hidden in a Greenhouse (EDEN), a rural square with rostrums steeped in time and history, a vibrant space juxtaposed with the course of the Cibin, a therapeuticgarden withstories, interventions in protected areas and much more, all of these and other equally important projects that have given substance to a section that has been vitrified by investment in recent years. The parks, squares and river courses proposed for development through urban regeneration projects, resulting from participation in architectural competitions, completed the section of public space hors concours, creating an exhibition that brought together, for the first time, the solutions selected by the juries of the competitions on the theme of public space development.

I have not set out now to review the participating projects, not because it would not be worthwhile, but because I would like to talk about any of them in a traveling tour of the exhibition, together with the authors of the projects. I hope at least to have piqued the interest of those who had the patience to go through the first reflections on the event, as well as leafing through the issue of Arhitectura magazine dedicated to BNA 2023.

Returning to the theme of the section, the public and community space is a particular subject in the current architectural landscape, with strong influences on the environment in which we want to live, a necessary evil, marginalized in recent years, but which is constantly trying to draw our attention from the oblivion in which it has been allowed to sink. Without intending to analyze historically, in a frivolous way, the morphology of public space, it has been influenced by its usefulness in the context of the times, starting from the Ancient Greek Agora, the Roman Forum, the medieval and Renaissance squares, the layouts of functionalism and modernism, and up to contemporary public spaces. Obviously, each model was marked by pluses and minuses, constituting important steps in the evolution of this type of space.

In a timid attempt to take a snapshot of public and community space, are we ready today to understand it and use it to its true value? Do we know what we need from public space? Most probably and more often than not, no.

The almost total neglect of spaces for the community has been acutely felt over the last 30 years, with small local interventions often being unprofessional fixes done through the landscaping services of town halls, with quick but short-lived results, not a natural consequence of a coherent policy for the treatment of public space or the respect of appropriate regulations. The city suffers in equal measure with its inhabitants, beset by cars lying abandoned on what has been erased even from the collective memory of ever having been a green space. The age of the car invasion still dominates us, not understanding the mistakes of cities that have gone through this stage before, but wishing for a landscaped public space that we have grown accustomed to using. Increasing the size of roadways to the detriment of pedestrian areas has turned out to be the local authorities' most handy solution, contrary to the results of any market research on the expectations and needs of citizens in a city that complains about the lack of green and planted spaces. We have reached a situation where the public interest has lost its value and, in the absence of professional intervention, local authorities have resorted to local solutions found on the spur of the moment, but which have often done nothing more than paralyze traffic and overcrowd cities. The uncontrolled expansion of commercial premises in the public domain and the monopolization of areas originally intended as public spaces have also been negative interventions in cities, altering the image of the architecture of buildings and the spaces between them. Excessive consumerism only creates a sense of social good life, constituting deep wounds in the natural development of the community. Terraces extending far beyond any property boundary encroach on the public realm, the pedestrian walkway becoming bordered by fences, flower beds and pergolas or terraces with roofs that are unfit for the urban image, in a cascade of aggressive and screaming elements, veritable frilly skirts attached to buildings even of heritage value, disrupting to the point of disappearance the perception of architectural objects or the flow of the historic street grid. The pandemic period in the second decade of the 2000s was an obvious disaster in social life, especially in communities where community life had values that had been handed down from historical times. Post-pandemic, on the other hand, the return to social life seemed more aggressive than before, with the refulgences and frustrations resulting from the measures imposed by the authorities, together with the need to recover the financial damage created by the pandemic, leading to an even more acute aggression in the public space.

A second invasion that we are facing today is that of the emphatic ideals that have entered the contemporary vocabulary regarding the concept of the ideal public space: socialization, interaction, inclusion, adaptability, identity. There are countless studies and research in the field, but putting these remarkable ideas into practice has been difficult, although there are examples of good practice all over the world and, more recently, in Romania. It is worth noting the huge discrepancy between the concept and objectives of a public space development intervention and the way in which the space is actually used. The dominance of virtual reality has turned places originally conceived for socializing into mere places of state for frenzied social network users, not infrequently finding groups of young people on the benches of local amenities who are more concerned with the information on their mobile phones than with the exchange of ideas and relaxation that we accepted years ago. Thinking that this is just a stage of evolution, a stage that is slowly beginning to be surpassed, the pleasure of experiencing the small joys of community life is found in public spaces responsibly landscaped by professionals.

Another major discrepancy noted is that between the concentration of public spaces in central versus peripheral areas of cities, with the concern to create quality public spaces in the city's extension areas almost entirely missing. The new housing estates, developed mainly on the basis of profitability, have extended the urban areas without sustainable development, without the presence of functions that complement housing, and the space between buildings is not a public space at all, but rather a non-existent, empty space. The local imposition of the provision of children's play areas as a condition for the issue of planning permission has, more often than not, created nothing more than petty and unsuitable spaces, thrown into residual areas of urban furniture and equipped with the cheapest pieces of street furniture or play facilities.

We all see and know all these things, professionals and non-professionals alike, whether we are acutely aware of them or not. What remains to be done in these circumstances?

I believe that good quality public space interventions should be promoted as much as possible, through all communication channels, so as to awaken public awareness of a convincing alternative to the spaces we have access to on a daily basis.

I believe that the approach to planning projects for public spaces needs to be rethought from the ground up, giving credit and value to professionals in the field from the planning stage, starting with a comprehensive debate involving civil society, a debate carried out not only with the help of architects, town planners and landscape architects, but also with professional communicators, involved in the design process alongside sociologists and psychologists.

I believe that local authorities need to be sensitized and, on the basis of the indisputable results on the quality of the solutions resulting from architectural competitions, to abandon direct purchases or tenders based on predominantly financial criteria.

I believe that we have a moral obligation as architects to use all possible means to re-educate civil society, provoking debates and organizing conferences open to the general public on the subject of public and community spaces, events promoting examples of good practice as an alternative to the existing situation.

I believe that we have all these obligations in order to be able to provide the generations to come with a future sustainable community space, adaptable to the needs of the community, because only TOGETHER we will succeed in doing these things.