Abstracție și conceptomanie

Abstraction and concept mania

| O democratică mise-en-scène a conceptualizării

Întrebarea - retorică, de altfel - dacă există Arhitectură fără concept, e legitimă în deruta în care ne zbatem. De la înalta lui poziție de concept filosofic, produs al gândirii multiplu distilate, termenul concept a fost democratizat cu inocență și generozitate (nu zic vulgarizat), de către toți producătorii de obiecte cu cât de mică natură creativă. A ajuns astfel să bântuie cu nonșalanță orice comentariu și jurizare, orice corectură, până și orice small talk între arhitecți - spre satisfacția diletanților, contrarietatea pedanților și îngăduința amuzată a connaisseurilor cu simțul umorului. Răspunsul simplu este: sigur că nu există arhitectură fără o substanță tematică, dar chestiunea e: în ce condiții i se poate asocia acestui nucleu germinativ al oricărui proiect calitatea de concept? Altă întrebare e: cât de riguroși e cazul să fim cu terminologia? Eu propun să fim toleranți, dar numai în cunoștință de cauză. Mai e de văzut în ce măsură abuzul de „conceptualizare” e nociv, inofensiv sau poate chiar benefic, adică stimulator. Dacă, de fapt, ideologia arhitecturală numită conceptualism nu și-a atins, în cele din urmă, oblic și retard, însuși scopul ei de fond - acela de a scoate din inerție cultura arhitecturală tradițională, de a o oxigena prin resemantizare și de a-i deschide noi orizonturi. Și asta cu riscul, previzibil, al devierilor. Acum patruzeci și cinci de ani, arhitectura conceptuală s-a lansat cu un înțeles limpede în lumea arhitecturii teoretice: O structură conceptuală este un aspect al formei vizibile - fie ea un desen sau o clădire, care este o idee. Ea se află acolo pentru a permite accesul în interiorul formei, către relațiile formale universale. …Forma fizică trebuie să conțină acea structură capabilă să abată privitorul de la percepția senzorială și să-l plaseze într-o atitudine conceptuală. Ea trebuie chiar să reprime posibila prioritate a unei reacții emoționale, pentru a permite o aproximare a intenției conceptuale1. Iată că, dacă acum o sută de ani istoricii de artă descopereau sufletul operei sub influența psihanalizei, în 1970, un arhitect pe nume Eisenman încerca să descopere categoriile „ființării” unui obiect, la sugestia filosofiei. Apoi, surprinzător pentru o ideologie ultra-elitistă, metadisciplinară, incisivă și extravagantă, ea a produs un mic cutremur. Urmat fiind de replici și replici la replici, s-a produs diseminarea ei. Dezbaterile au depășit cercul inițiaților prin cei care au tălmăcit lucrurile pe înțelesul arhitecților, temperând cerebralitatea tezei și dând interpretări mai plauzibile. În fine, reverberațiile au tot difuzat, tot mai diluate, penetrând până la urmă vechea noastră arhitectură lumească, cea înfrățită cu realitatea și cu speranțele, satisfăcând nevoi și producând emoții, cum o știm de mii de ani. Păstrau totuși destulă virilitate cât să-i mai destabilizeze din certitudini și să ne tulbure nouă mințile noastre de arhitecți cumsecade. Vreau să spun că ne-au tulburat „gândirea verticală”, logică, liniară și antrenată la școală, cea de pe partea stângă a creierului și ne-au forțat să ne mutăm eforturile pe dreapta, la „gândirea laterală”, cea a nisipurilor mișcătoare pe care dansează creativitatea și soluțiile euristice. A urmat popularizarea generalizată a conceptului, cu derapaje și malentendu-uri, până când a căpătat tot atâtea înțelesuri, câți arhitecți pe pământ. În felul acesta lucrurile s-au stabilizat până la urmă, printr-un soi de compromis pe care fiecare arhitect l-a realizat, după posibilitățile lui, cu partea așezată și cu partea nărăvașă a creierului. |

| Citiți textul integral în numărul 6 / 2014 al Revistei Arhitectura |

| NOTE:1 Peter Eisenman, Notes on Conceptual Architecture: Towards a Definition, în Design Quarterly 78/79, 1970. A conceptual structure is that aspect of the visible form, wheather it is an idea in a drawing, or in a building, which is intentionally put in the form to provide acces to the inner form or universal formal relationship. …In order to approximate a conceptual intention, the shapes which are perceived would have to contain a structure whitin their physical presence which would have the capacity to take the viewer from the sense (immediate) perception, to a conceptual attitude, and at the same time requiring of this structure a capacity to suppress the possible primacy of a sensual response. |

| A democratic mise-en-scène of conceptualization

The question - entirely rhetorical - whether there is Architecture in the absence of concepts is legitimate, given the current confusion in which we find ourselves. From his superior position of philosophical concept and product of repeatedly distilled thought, the term of concept has been subjected to an innocent and generous democratization (I shall refrain from saying “vulgarization”) by all producers of objects containing a however small amount of creativity. And so it happens that now the term is popping up hauntingly in any comment, jury grading, correction, even any small talk between architects - to the satisfaction of dilettantes, the bewilderment of pedants and the amused tolerance of the connoisseurs with a sense of humor. The simple answer is: of course there is no architecture without a thematic substance. The question is: under what circumstances can the germinating nucleus of any project qualify as a concept? Yet another question would be: how rigorous should we be when it comes to terminology? I would opt for tolerance, but only with full knowledge. We should also see whether the excessive resort to “conceptualization” is harmful, harmless or possibly beneficial, i.e. motivating, and whether the architectural ideology referred to as conceptualism has ultimately, in oblique and belated fashion, achieved its very goal of putting an end to the inertia of the traditional architectural culture, of revitalizing it by ascribing new meanings to it and of opening new horizons. All this, while running the predictable risk of deviations. Forty-five years ago, conceptual architecture was launched with a very clear meaning in the world of theoretical architecture: A conceptual structure is that aspect of the visible form, whether it is an idea in a drawing, or in a building, which is intentionally put in the form to provide access to the inner form or universal formal relationship. … In order to approximate a conceptual intention, the shapes which are perceived would have to contain a structure within their physical presence which would have the capacity to take the viewer from the sense (immediate) perception, to a conceptual attitude, and at the same time requiring of this structure a capacity to suppress the possible primacy of a sensual response.1 And thus, one hundred years ago, art historians discovered the soul of the work under the influence of psychoanalysis, while in 1970 an architect by the name of Eisenman tried to discover the categories of an object’s “being” following the suggestion of philosophy. Then, quite surprisingly for an ultra-elitist, meta-disciplinary, sharp and extravagant ideology, it produced a small earthquake. The earthquake was followed by aftershocks and aftershocks to aftershocks, which caused its dissemination. The debates went beyond the circle of the initiated thanks to those who translated it to the understanding of architects, mitigating its pointed intellectualness and endowing it with more plausible readings. Finally, its increasingly diluted reverberations reached our old mundane architecture which nurtures on reality and hopes, satisfies needs and produces emotions, as we have known it for thousands of years. It was still strong enough to shake some of its certainties though and to trouble our thoughts of good-natured architects. What I mean by that is that it troubled our “vertical thinking”, logic, linear, school-trained, formed in the left part of the brain, and forced us to shift our efforts to the right side of the brain, to the “lateral thinking”, the quicksand, harboring creativity and heuristic solutions. What followed was the generalized popularization of the concept, with deviations and misunderstandings, so that the term ended up gaining as many meanings as there are architects on Earth. Things settled finally and a sort of compromise was thus reached, by each architect in turn, according to his possibilities, between the good side and the naughty side of his brain. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine |

| NOTES:1 Peter Eisenman, Notes on Conceptual Architecture: Towards a Definition, in Design Quarterly 78/79, 1970. A conceptual structure is that aspect of the visible form, wheather it is an idea in a drawing, or in a building, which is intentionally put in the form to provide acces to the inner form or universal formal relationship. … In order to approximate a conceptual intention, the shapes which are perceived would have to contain a structure whitin their physical presence which would have the capacity to take the viewer from the sense (immediate) perception, to a conceptual attitude, and at the same time requiring of this structure a capacity to suppress the possible primacy of a sensual response. |

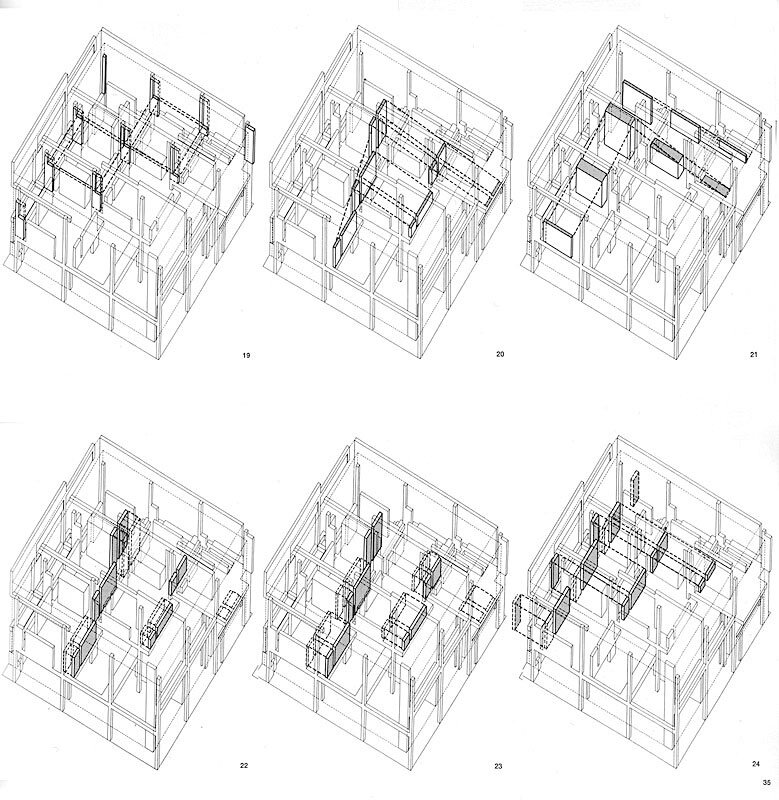

Peter Eisenman, House II (Falk House),

în Hardwick, Connecticut. 1969-70

Marcel Duchamp,

Roata de bicicletă

(o lume cu fundu-n sus), 1913

Peter Eisenman, House VI

(Frank Residence), în Cornwall,

Connecticut. 1975

Numărul revistei Arhitectura cu tema CONCEPT/ABSTRACTIZARE va fi lansat marți 27 ianuarie, la ora 17.00, în CCA-UAR, strada Jean Louis Calderon, nr 48. La lansare vor fi prezenți următorii contributori: Augustin Ioan, Francoise Pamfil, Anca Sandu Tomașevschi, Florian Stanciu, Ștefan Vianu. Mai multe detalii puteți citi aici sau accesând pagina evenimentului de pe facebook.