Do you like public space?

Thematic folder

DO YOU LIKE PUBLIC SPACE?

Debate with specialists in architecture

urban planning and built heritage

moderators: Adrian CRĂCIUNESCU and Gabriel PASCARIU

text processing: Gabriel PASCARIU

The title of the professional debate, which was held in the premises of the Oradea Fortress, in the redeveloped spaces in the fortifications area, was suggested by the similar theme and title of the 2014 issue 18 of the magazine Urbanismul Serie nouă. The debate was attended by about 20 guests: participants and laureates of the two sections of BNA 2018, hosted by the municipality: Section 3 - Restoration. Consolidation. Buildings returned to communities and Section 5 - Inclusive Public Space.

A selection of the main ideas expressed is presented in the following pages. In the opening, Mr. arh. Crăciunescu gave a presentation accompanied by images, related to public space and heritage protection, in the context of the process of drafting the Cultural Heritage Code, after the publication of the preliminary theses1 in 2016. A summary of this intervention, which also aims at connecting the thematic of the two sections, is presented as a preamble to the above-mentioned debate.

Urban solutions for an efficient and intelligent protection of heritage

The most interesting public space is usually bounded by private property, the frontages of buildings located on these properties, their gardens and enclosures. At the same time, it can be said that there is frequent confusion in society between public space and the public domain, two clearly different concepts, including from a legal point of view. The consequences are direct for what we want to be protected built areas, for the way in which we have the administrative capacity to control this space.

More than a century ago, a building in New York2 generated the first piece of planning regulation that prohibited buildings of a certain height and plot occupancy, requiring setbacks as the height increased. Previous building techniques had never questioned the fact that a person could build so massively that neighbors would be almost totally deprived of direct light over such a large area. Half a century ago, Paris was taken by surprise by the Montparnasse Tower. This, in turn, led to a change in the bylaws, and Paris subsequently banned buildings higher than seven storeys in the central area.

We are also very late to be affected by this real estate pressure, which has a direct effect on public space, and urban planning regulations are ill-prepared for this boom, just as they were in New York and Paris a long time ago. In our current parlance, the land beats the house. As long as the price of land exceeds the price of the building on it, the tendency will always be to demolish and build densely, and the owner cannot be blamed because he will always want to make the most of his property. On the other hand, we are no longer long in a situation in which the state had total control over property and how it was demolished and built. Today, we have been in a great dilemma for some time: how to preserve a certain character of public space, but not have to prohibit owners from developing their land on high ground? Can we find a fair solution to the simultaneous need for conservation and real estate development?

Turning to the American example, there is a British-derived concept called "air rights development" which means that a landowner can build as high on his or her plot as financial and technical resources allow. Although the advent of aviation has led to the imposition of a limit, the margin is still very wide, with regulations still aimed at densities rather than heights. One consequence is that the person who cannot use the space can sell his or her building rights to the owners of neighboring lots. In other places influenced by British law, such as India, this tool has been used in other forms. There, a form of expropriation is practiced to widen roads without budgetary expense. In this way, someone who lost a piece of land would instead acquire additional building rights on the remaining land, in financial compensation for the land taken by the community. The same principle of "transfers of building rights" is also used in Australian cities that regulate densities3, such as Adelaide or Perth. The regulations include this option to protect architectural cultural heritage by setting an average density and a distinct development area where those rights can be transferred (so not to neighbouring plots as in New York4) for additional building ("bonus plot ratio"). This means that if you have a protected building with a height two storeys below the regulatory average, you can sell the building rights for those two virtual storeys to an investor who can add to the rights they have in the development area designated for such transfers.

Coming back to us, we can see that most local administrations, but also most architects, have the hubris to create "urban landmarks" everywhere. One such landmark was planned to be a huge tower designed by Zaha Hadid's studio on a plot of land made up of five plots of land between Eminescu, Dorobanți and General Ernest Broșteanu streets. After multiple attempts to temper it with alternative options proposed by Dorin Ștefan's studio, the municipality procrastinated in approving the urban development plan and, in the end, it seems that the real estate plan collapsed after more than 10 years. In the case of the 'Mihai Eminescu' ZCP, the problem stems precisely from the way in which, in 2000, this coefficient of65 was established, by referring only to the precedent of the particular cases of inter-war and 1960s buildings on the southern side of this street, most of which were built when Dacia Boulevard was pierced.

This is where the timeliness of the draft legislation of the Cultural Heritage Code comes in, which is based on 10 principles, two of which are very relevant to this example. The principle of citizens' responsibilities shows that heritage is the responsibility of every citizen, but it should not be a burden for anyone. That is, if one of two citizens with equal rights is able to profit from his property and the other is restricted because of a public interest, the latter will feel this as a burden. The equitable consequence would be that society should compensate him or create alternative opportunities for him to have the same economic opportunities as his neighbor unaffected by such restrictions. On the other hand, a principle is stated which is in fact an old one, dating back to the 1975 Amsterdam Declaration on the protection of the architectural heritage, the Venice Charter and the Granada Convention. It says that heritage is not only the object, the monument itself, but also its context, sometimes on an urban scale, a context which is not necessarily made up of monument buildings, but of small, apparently modest buildings, but which together generate what we like to call a protected built-up area. Take a relatively recent example from General Dona Street in Bucharest. There, for a long time, a house was advertised for sale. But the advertisement said "land for sale", as if the house could be demolished at any time, even though, by chance, the house belonged to the very general who gave the street its name. How do we avoid such situations?

The best option would be to establish a development zone with maximum coefficients in the Urban Development Plan, on top of which a reasonable range could be added to absorb the bonus areas that cannot be realized in the protected built-up areas, due to the restriction of some developments in relation to a certain average. In order to prevent speculation, these rights, once realized, would be entered as encumbrances in the land register for a long period of time. In this way, the owner will no longer complain that he has not been able to realize the potential of his plot, and those who would buy such a property after it has already reached its full potential will know from the outset that they are not "buying land", but are buying an existing situation, at its real potential and not speculative potential.

The good thing about this mechanism, which is designed to provide stability and predictability as to the character of protected built-up areas, is that it does not involve any public funding resources at all, but only the interest of local government to regulate, through planning regulations, where such transactions would take place and where the development rights could be transferred. The end would be a fair way to preserve our protected buildings without public costs.(Adrian Crăciunescu)

Public space trends and challenges in Romania

Gabriel PASCARIU: What is happening with public space in Romania today? What's happening with public space in protected areas that pose certain problems? We are in Oradea and colleagues from the municipality can certainly tell us a lot about what is happening here with public space. Public space is a broad topic, which has been more and more intensively and widely debated in the last two or three decades. In this context, we can talk about the very many forms that public space can take, from the very wide open - such as Lisbon's Praça do Comércio, for example, facing the Tagus (Tagus) river -, to the enclosed - such as the renovated and rebuilt Rynek Starego Miasta (Old Town Market Square) in Warsaw - or semi-enclosed - such as the Great Square in Sibiu - to the promenade, such as the countless canal paths that criss-cross Dutch cities. Public space, in its various guises, is today an increasingly important part of urban space and we could expand the subject even further if, in addition to open public space, we were to talk about enclosed or semi-enclosed public spaces (museums, sports halls, stadiums, etc.), some of which are privately owned but of public interest - such as shopping centers - which now often replace traditional public space. There is no shortage of the latter in Romania, as they have proliferated spectacularly in major cities over the last two decades. For today's discussion, I propose to seek together answers to the following two questions: What are the main trends in the approach and configuration/reconfiguration of public space in Romanian cities? and What problems and challenges are involved in intervening in the public space in protected areas or areas of protection of historical monuments? And since we are in the Medieval Citadel - an emblematic place, recently recovered and restored in the city of Oradea - let's also talk about the public space in Oradea: past, present and future.

Ioan Andreescu: What are the main trends in public space in Romania? The main characteristic in the approach to Romanian public space is the dance of indecision and the difficulty to adopt a viable long-term strategy. Where we talk about successes, as in the case of Oradea or Alba Iulia, they are all very similar in terms of the relatively high speed of the process, the approach of clichés standardized in the previous period in other countries, known superficially from practice and literature, and the blithe neglect of the socio-economic aspects of substance to support solutions. That would be the trend and, obviously, the positive side, that there is a certain momentum that ends up stimulating or "shaking up" the political factor. In Romania - which adopts principles of empowering social life through civic structures or liberal economic policies - the only element that generates urban regeneration movements has remained a political factor lacking many of the tools it could have had previously.

Second issue: what are the challenges? Well, the challenges stem from the fact that we still have a complex geometry: there are NGOs that scream for the protection of heritage, but have no idea what heritage is, how it should be protected and how it can contribute to the public space, there are ambitious politicians who want to create their image and quickly promote often ill-considered interventions and operations to capitalize on public and heritage space. Finally, there is also a great public appetite for the playful and entertaining side of this type of operation. People see it as a kind of fun fair. The scenery is there, there is cheerful lighting, and the problems of the central areas, from a social, economic or infrastructural point of view, remain unresolved anyway, and then the Beer, Wine, Street Food Festival and the like is organized, and of course we have a glorifying civic discourse, which is slammed into this reality like a nut on a wall.

In our country - because I have seen this in Timișoara and in other cities - there are no real debates on these issues of regeneration and the valorization of public space. There are, as a symptom of the fragmentation of society, howls from certain areas, from NGOs or all sorts of associations, which, put together, form a kind of unusable cacophony, and there are bursts of activism on the part of local government and a very high level of willingness on the part of the population to accept this as a kind of entertainment, a kind of amusement park into which the city can be transformed. In the end, everyone is slowly falling in line with this formula of the continuous fair. It's a fair of vanities, as Thackeray said in the introduction to his famous novel: "People are so stupid that they fight so desperately over things that are not worth the slightest thing". Are we in "the muddle of vanities"? Reread the classics to find the answer!

G.P.: We seemed to start on an optimistic note, but the ending...

Stefan Paskucz: The temptation that Mr. Andreescu gave is really a reality. I don't think it's a negative undertone. I would go even further: this "fairground" is also terrorizing, i.e. you can't even go out in the Citadel, because trucks could run over you and you could die6. My daughter phoned me a few days ago, it was Liverpool Days and, because there was a super-demonstration, the "Citadel" was closed. She said they used so many "battalions" on all the streets to keep the whole city guarded that it scared the children, machine guns only... all the streets were closed. We go back to the Citadel and we barricade ourselves, we lock ourselves in... That's a challenge, defense is starting to become a reality.

(...)

I.A.: Another kind of fairground is emerging. The guarded bazaar. And this mechanism is very interesting: globalization has produced some perverse effects. In the name of freedom of movement, it has allowed the destruction of the social fabric that has been built up in many parts and the introduction of nuclei of danger and pressure, which have been deliberately created, not born accidentally, by the introduction of huge masses of migrants. Now you have to respond to it and then the fair moves into fortified enclosures. After all, that's the way it used to be, right?

Education for the public space

Iris Popescu: In the case of Bucharest, we don't have real public spaces, but only commercial spaces, which are the only ones that are functioning at the moment, and I think the biggest problem of our team of urban planners is, in fact, the lack of education of the population in terms of public space. And not only that, but a community resignation. People have gotten used to not having this public space... it's a constant battle between pedestrians, cars, etc. - we all know. In the last couple of years, there seems to have been a lot of growth in people's desire to get involved somehow, but they still don't know how to do it. Examples like Street Delivery, which tries to bring communities together around common problems, could be a solution to involve civil society more and more.

Dan Costa: If I had to summarize in a few words, the conscience of public space is the mall. In the magazine "Architectural Design", in the 90s, there was a series of articles by Denise Scott Brown on urban design, which distinguished between public space, with its social attributes, therefore civic space, and community public space. Public space is where we carry out our immediate needs in the community. The civic one, which actually defines us, is the one that also has attributes of civic identity, values, beliefs, history, identity. Providing civic attributes to a public space requires education. Architecture and urbanism alone cannot do it.

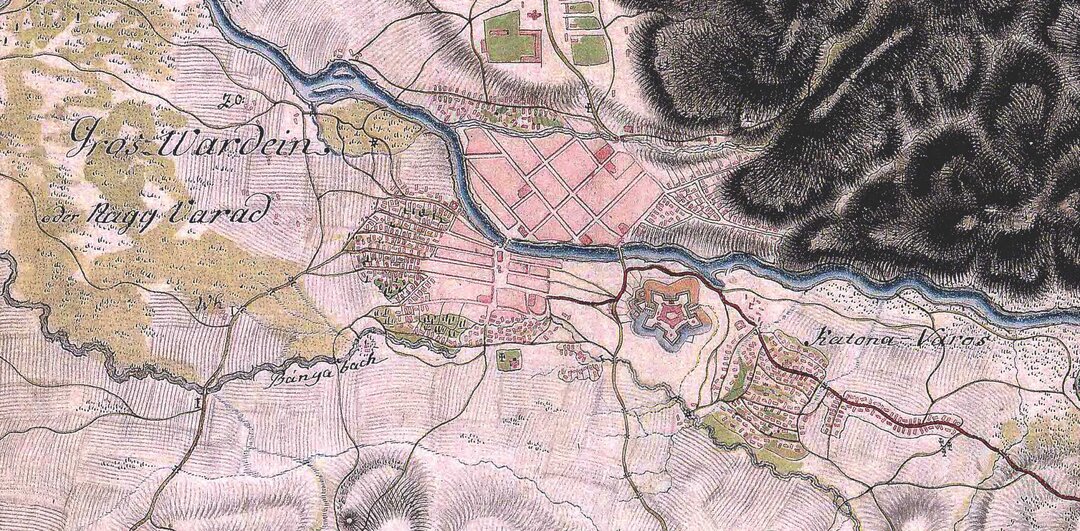

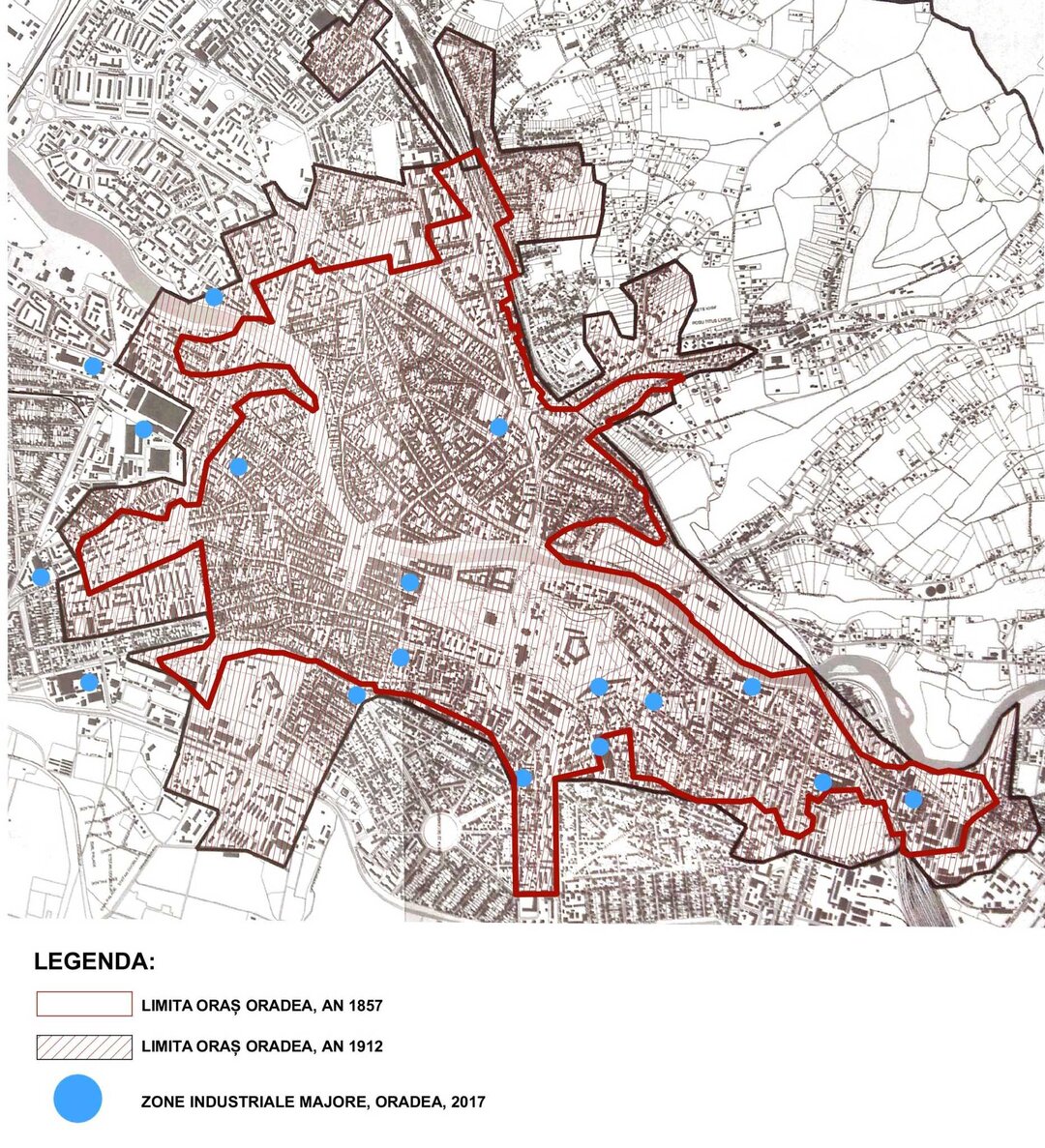

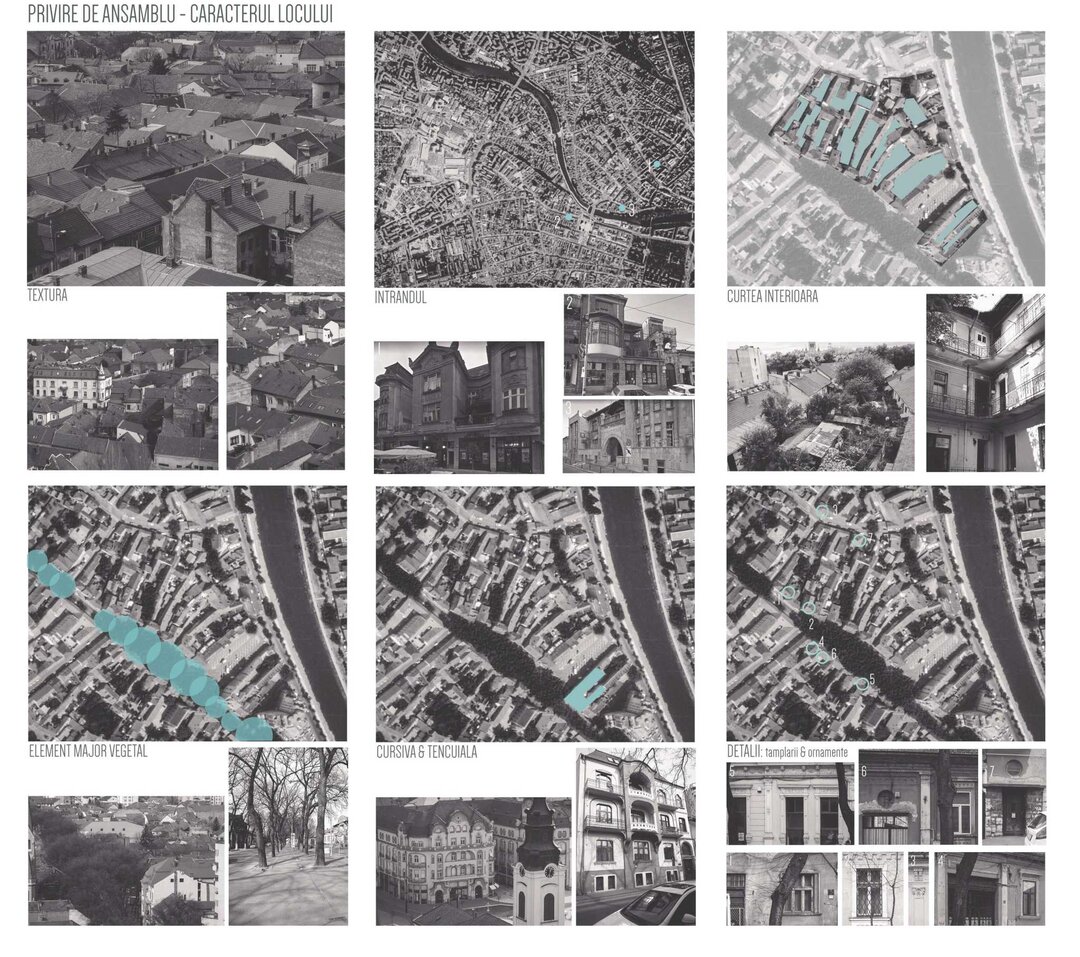

Oradea is very lucky. Oradea was built in 40 years, from 1880 to 1920. It has this extraordinary stylistic unity, it's the end of classicism, the final eclecticism and then everything is Art Nouveau, Jugendstil, Secession. From Vienna, the style spread here, and our few leading architects, like Rimanóczy Kálmán, father and son, Komor Marcell, Sztaril Ferenc, created this stylistic unity, which gives the city the charm it has today. You can't ruin it or destroy it, they tried that in the 60s and 70s, when many cities fell victim to the architectural intervention of the time. Oradea wasn't, because it was already completed and finished, unified. What you can do now is just maintain, clean, not densify.

G.P.: How do you see the recovery of the Citadel in this context, as a public space?

D.C.: Beneficial. It frees up the actual center, the Union Square... It's the social load, if there are fairs, which are interesting and beneficial, they occupy this space, which is only good for that. Because it's not in the hustle and bustle of urban mobility.

G.P.: More disguised fairs, a little more hidden, not in plain sight.

You need vision, good use and maintenance of public spaces

Ernest Pafka: I would perhaps slightly contradict my colleague. I've been in Oradea for 42 years and for 25-30 years I've had major works with the local administration, with the City Hall, as beneficiary. My opinion is that we do not know how to maintain public space, even if we have it. The new PUG is much more interesting than the previous one, which was too permissive and any investor could do anything based on an urban planning documentation. Concerning public spaces, let me give you some examples: the Union Square - which is the central square of the city and, over the century, it has had several transformations. There was an architectural competition. Three competitors were invited to propose solutions. Three of my colleagues worked on the Union Square, Emődi Tamás won, he came up with a very simple solution and it was approved. He designed the execution project, the tender for the execution started, two competitors participated, two companies that were both disqualified and then, at the decision of some people in the City Hall management, the whole project was changed. This is what you see. It would be very good if it would be used for quality events... there was a Turkish fair, fantastically well organized, with I don't know how many pavilions, there were enough people, they also came with products, it was very interesting. There are also medieval music concerts which are appropriate for something like that.

G.P.: You talked about the maintenance and the difficulties here. I think it's not only a lack of skill, knowledge, know-how at the level of the administrations, but also really a lack of resources, because public spaces require a lot of resources for good maintenance.

I recently held a student workshop in Mangalia, a town which has all six resorts on its territory and manages all six resorts on the south coast. It is distressing to see the deplorable state of the public spaces - streets, squares, promenades, etc. - in these resorts and the real inability of a municipality of 40 000 inhabitants to maintain the huge public space of these resorts. The second issue is the lack of transparency in the design of public spaces. This aspect is also linked to an observation I have made about the projects entered in Section 5, dedicated to public space: far too few in relation to the relatively large number of interventions in recent years. One of the explanations - based on discussions with many designers and beneficiaries - is that it is impossible to assume clear authorship of the solution implemented and the design.

Planning and accountability are needed

Andrei Luncan: What has been discussed so far emphasizes, in a way, what I wanted to tell you: the fact that at the level of urban planning, at the level of legislation, the public space, the community space are completely uncovered. There is not, or at least I am not aware of any urban development plan which, in the development stages envisaged, in the 10-year period, at least provides for the redevelopment of existing public spaces, let alone any coherent proposals for public spaces. On the other hand, the total lack of coherent strategies for rehabilitating or integrating public spaces into the urban space, into the life of the city, in fact, leads us once again to a paradox: if we take all the public spaces, and I am talking about the major ones in Romania in recent years, we come to the conclusion that we are returning in one form or another to the large administrative squares of the previous period. As Ernest (Pafka) said, the Union Square is, in fact, a simple transit space and that's all. You cross the Union Square and you can possibly sit down for a coffee, a beer or a chat during the day. There is a bit of animation in the evenings, when the square is indeed invaded by children, but these things I think are involuntary. There has not been and there is not, in my opinion - I don't know - an area of Romania that has a strategy for the development of public spaces in the coming years.

On the other hand, what needs to be discussed is how these spaces are maintained. When I am talking about maintenance, I am not talking about putting up pansies and tulips, but about a different kind of maintenance, which should be normal for the public space in question. There is something else that I also think is very important: the almost total lack of communication and dialog on this issue between the administration, politicians and the citizen. All the time, those of us who call ourselves specialists talk about the fact that citizens have no culture, no urban culture, no culture of this, that, etc... Yes, but who is trying to educate these people, who is trying to dialog with them? Here the Oradea City Hall has made some attempts... The attempt is an interesting one in theory. There has been an attempt to launch some challenges to the citizens, through which the City Hall requests, and this is a very good thing, proposals for intervention in the public space from citizens. There is an amount allocated. After a second round, the maximum level of this allocation has not yet been reached. Why? Because not enough relevant proposals have been made. On the other hand, Oradea has also tried to involve citizens not only in the maintenance, but also in the varied use of space in areas built during the communist period. The results are sometimes catastrophic. Owners' associations have been forced to take over management of areas in the immediate vicinity of a condominium. Some were happy, some were already doing it. This led to all kinds of gaudy, wooden, wrought-iron. There's an already famous example on the Hungarian border, where an association has set up a mythical area where there are four benches and in the middle a wooden mill that's tied to the water with pebbles... The way their public space fits into the urban landscape is more than questionable, given also the location in such an area where it has a strong visual impact for those passing by. It is absolutely bewildering. What is the beneficial mechanism for the Romanian public space?

E.P.: It's mine, I do what I want. Public awareness is not a matter of education.

A.L.: This is my point. The fact that as soon as I try to take responsibility for a public space, it is considered to be mine and, if it is mine, I do what I want with it.

D.C.: It is also related to what Mr. Andreescu said yesterday, in his speech about the jury and the evaluation of works: the tendency to appropriate a given space by a specific community, directly using it.

G.P.: The transfer of responsibility is necessary and can be a first step, but it is obviously not enough.

A.L.: But also this transfer... In my opinion, there should be a different kind of regulation, not town planning or building legislation. To be able to see how far I can go with public space. And I would have liked, but perhaps this could be a topic for a future round table, to deal with the public space inside shopping malls, which in certain situations has devastating effects, not necessarily on urban space. It is a trend, we are about 60 years behind others, all civilized countries have gone through this - the transfer of public space inside such buildings, and then transfer it back outside.

Political decision and the need for management

Adrian Crăciunescu: I think there is always confusion between public space and public domain. I think it is not by chance that the prizes in the section dedicated to public space were awarded one in a protected natural area and the other in a public space generated by a historic space. These become the most interesting spaces. Like in Oradea. In our country there is another confusion between general urban plan and vision. I believe that the master plan should reflect a vision. Often, however, there are urban plans that are simply administrative, without a vision behind them, which sometimes leads to the imposition of political decisions. For example, the location of the Orthodox cathedral here, in the axis of a previous development with the blocks, which would probably have created a gateway to the Citadel, turns a public space into a barrier that screens the Citadel and leaves it behind, like in many other situations in the 70s and 80s when things were hidden behind blocks.

A.L.: I disagree with you on the openness. The cathedral was located here politically, because this was supposed to be the political administrative headquarters. That's why this space was created, not because the communists thought to create a gateway to the Citadel.

E.P.: It's an old policy. There was a survey in Oradea right after the regime change. "Do you know that there is a Cetate in Oradea?" A large percentage of respondents said no. "Have you ever been to the Fortress of Oradea?" Not even 10% had. It's true that at that time it was not visitable, but it was not forbidden either. "Where is Oradea Fortress?" Most respondents didn't know where it was. The two housing complexes were built with the idea of creating a new center. The land in the middle was left empty, because the political-administrative center was also intended to be realized with its back to the Citadel. There was also a competition for the political-administrative center there. Fortunately, the idea fell through and nothing more was realized, but there were some works that destroyed the remains of the bastion in front, which is right where the cathedral is now. They didn't do any archaeological research, absolutely everything was destroyed.

A.C.: The fortress was not important in their vision and you can see this very clearly in Alba Iulia, because there too the blocks were built on the principle of masking, of not integrating. It is also a question of management and strategy which must be reflected in the urban development plan. I would come back to the first point which relates to this: the issue of the public domain and public space.

Back to the need for education

I.P.: You talked about appropriation, maintenance of public space and you mentioned public utility. I have all of the grievances that have been said at this table and I'm going to get to the issue of education. We need to endeavor to get involved in educating people and the community.

A.C.: It's long term, because we all agree that education will take its toll sometime late, but we also need short term solutions by strengthening public authority, which should be much more present in the public space, which is not happening very much, unfortunately.

And we conclude

G.P.: I think we can go on for a very long time. The topic is extremely interesting and has many ramifications. The discussion has been extremely interesting. I would just like to run through a few ideas that came up in the debate. There was talk about the multitude of actors involved in the issue of public space, in different ways, with different resources, capacities, knowledge and hence a complex and not always very coherent interaction. We have talked in various ways about strategies, about the lack, in fact, of strategies, of vision, about how public spaces should be approached, about the tendency to approach solutions, solutions to public spaces, often to satisfy certain playful, easy interests on the part of the public and with the idea of maintaining a certain state of mind that may not always be beneficial. This gives rise to various forms of aggression in public spaces, which are not only physical or visual, but also auditory, olfactory and sensory, and solutions and regulations, including legislation, should probably be discussed and found. The need to maintain public spaces was discussed from the point of view of specific approaches, which do not mean simple cleaning or cosmeticizing. The ways of realization and implementation of solutions for public spaces were again discussed. There was a lack of serious debate, a lack of proper communication between these main actors, this triad of public administration, specialists and the community. They also talked about the need to find a correct meaning, a concept, to define more clearly what public space can be in its various guises and, last but not least, about the risks that public space faces today in the face of new forms of aggression, such as terrorism, which is already manifesting itself strongly in certain places and is causing changes in the configuration and use of public spaces. There were other points raised. Thank you very much for your participation.

NOTES

1 HG no. 905/2016 for the approval of the preliminary theses of the draft Cultural Heritage Code. MO, Part I no. 1047 of December 27, 2016.

2 Equitable Building, built between 1912 and 1915, with a land use coefficient approaching 30.

3 In contrast, Melbourne did not restrict height or density in relation to property areas until 2015, however, when a maximum CUT of 24 was considered! (https://www.urban.com.au/news/interim-central-melbourne-planning-controls-the-detail, accessed August 2019).

4 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trump_World_Tower (accessed August 2019).

5 Close to the Manhattan average where it is 6.8 but well above Paris where it is 3 (according to: https://andrewlainton.wordpress.com/2011/07/11/floorspace-area-ratio-making-it-work-better/, accessed August 2019).

6 Alluding to the Nice bombing on July 14, 2016, when a 19-ton truck deliberately drove a 19-ton truck into a crowd on the Promenade des Anglais, killing 86 people and injuring 458 others.