The city and the citadel

Thematic dossier

City and CitadelStaff and heritage

Text and photo by Kázmér KOVÁCS

In the summer of 2015, my first cousin's mother would have turned 100. We met in Arad, where our common grandparents lived, and on the day of the anniversary we traveled to Oradea, her hometown. We visited, briefly, the Ullmann Palace, the Secessionist building in which the apartment where the birthday girl once grew up is located and where, one day, the porters came to take everything from the house, because my maternal grandfather liked to play cards; on the day in question, before leaving, as usual, to spend the day at the café, he turned around and announced the imminence of the event.

The Ullmann Palace was holding up relatively well, although the architectural quality of the building would have deserved a better fate than that to which the deteriorated finishes and vernacular improvisations were testimony. Moreover, the building - in its full name the Kurländer and Ullmann Commercial and Residential Building, built between 1909-1911 and the Secessionist work of the architect Ferenc Löbl1 - is listed as a historical monument.

Of course, the reasons why the building is listed as a historical monument differ from the reasons why my cousin and I visited it (his father was my mother's older brother), but both systems of reference are in the same register, that of remembrance. Our time there left no significant mark on the history of the building, even though my cousin wore - unostentatiously, admittedly - the saffron-colored silk shawl of Thai Buddhist monks. After his departure for Budapest, I came back from the train station to take a few photos, then sought out the Citadel, which I had learned had become accessible.

Accessible, yes, but locked up, as befits a fortress: it was still under construction and it was also the weekend. After a friendly chat with the guard at the gates, I was allowed to wander freely among the bastions, the pillboxes, the church, the countless corridors and rooms. Photographs can in no way illustrate the familiar yet unique taste of adventure. The memory of it will stay with me for a long time with the same brilliance, even if, in return, my passing there will have added only an infinitesimal speck to the countless layers of meaning that have made the Citadel of Oradea an important historical monument.

On the way out, in the defense ditches, today transformed into a promenade, I met newlyweds. They were taking photos of the newlyweds dressed for the occasion. Then we met a second and a third wedding procession. The backdrop of bastions and battlements, the vicinity of water mirrors with blooming water lilies will create a special ambiance for these monument-pictures, meant to conveniently fix in time and space that unforgettable day for the newlyweds.

Bricklayers, visitors, brides... all these have been and will be in the history of the citadel. However, the anonymity of the passing by does not change the fact that their multitude superimposes imperceptible glimpses of remembrance which, with the passage of time - perhaps another millennium of peaceful use - will probably change, from the foundations, the heritage significance of the Oradea Fortress.

This is how historical monuments are born. No brilliant architect can design them, they are "made" by the (generally involuntary) contribution of all those who linger for an hour or a lifetime within their walls.

Ullmann

The Citadel of Oradea has recently undergone an elaborate restoration. The centuries-old military structure has thus been converted for urban, civilian and peaceful functions. It remains to be seen to what extent contemporary societies and their leisure culture will be able to build an everyday life comparable in meaning and consistency to that which a military garrison (or ruin) of any era could generate. The task, now, is to find sufficient resources for the sufficiently intense inhabitation of these walls, envisioned for quite different functions and suited to quite different activities. A vast defensive complex of buildings and defensive arrangements, shaped over many stages of construction and reconstruction (usually following prolonged sieges, whether or not resulting in defeat), the citadel will henceforth be inhabited by different people2: students and teachers, participants in artistic festivals or cultural events of all kinds; it will house public and private, cultural and administrative institutions, and will be visited by tourists. At present, the permanent function of the fortress is to house the Faculty of Visual Arts of the University of Oradea, which illustrates the paradoxical versatility of the original military function and the heritage importance of the ensemble.

In an attempt to contribute to the perception of the Fortress of Oradea over time, I will not go back over the stages of its construction, which are all too well known, nor will I comment on the more recent strategies of enhancement, which naturally focus on the openings to possible inhabitants of the present3. The former sufficiently explain the existence of this vast structure built in the middle of the city; the latter seek the long-term economic sustainability of the city. The former are a prerequisite for good intervention, not only in terms of restoration, but also in terms of exploitation; the latter make it possible to reintegrate this exceptional historical monument into its functions, but if left unused, it is condemned to the mucified destiny of a gigantic architectural curiosity.

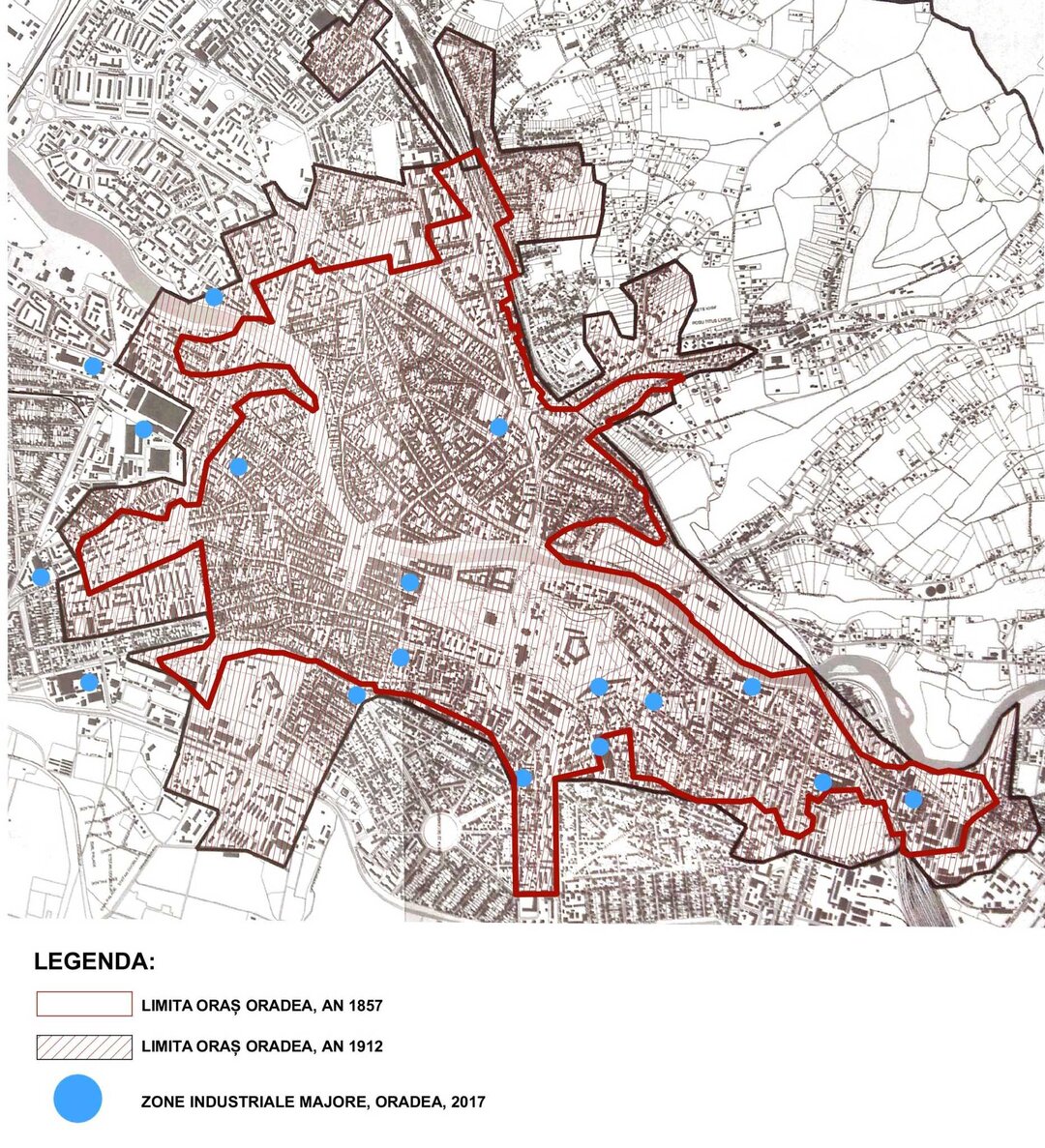

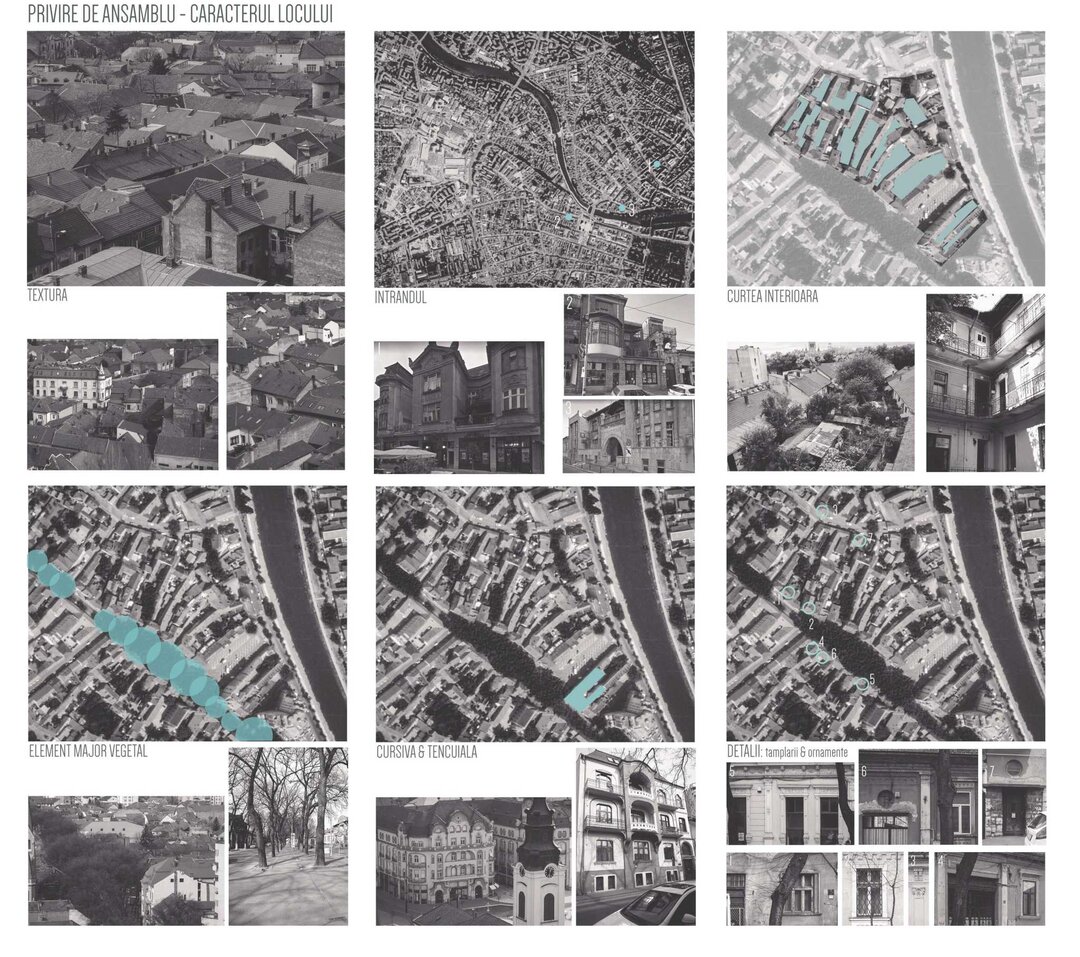

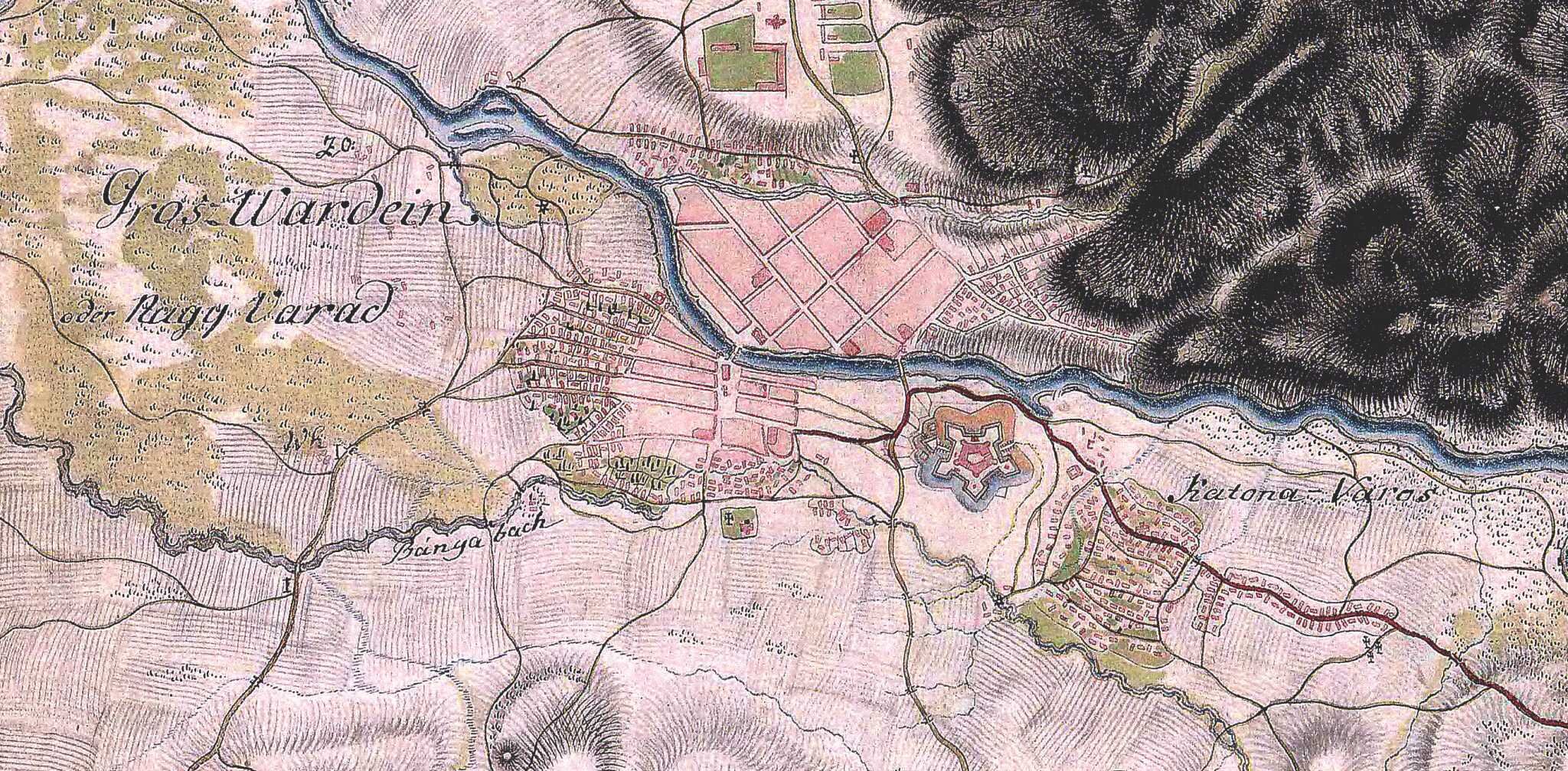

A cursory glance at the satellite view of Oradea reveals the strangeness of the presence of this ancient structure in the urban fabric4. Responding to entirely different needs than those of 21st century habitation, the fortress - with its not quite regular five-cornered star-shaped plan, with a concentric pentagonal building inside the double, triple, sometimes quadruple fortification enclosure, which became increasingly complex as warfare techniques developed - reminiscent of the ideal city plans of Philarete (the Sforzinda city plan) or Scamozzi, whose utopian project became a reality - Palmanova is a nine-cornered star-shaped city in the Veneto region5.

Fortress

The similarities between the ideal city projects and military structures configured according to an abstract geometry stop at their isomorphic character. In most places, both citadels and traditional cities follow to a good extent the topographical data of the terrain, adapting to them and tailoring them to the needs of specific civilian or military habitation6. For the rest, urban settlement, with its always significant diversity of social groups and occupations, differs fundamentally from the predominantly military settlement which, with all its accessories, has become obsolete in the vast majority of European fortifications built in different eras. This is due not only to the state of relative peace on the continent, a reaction to the monstrous scale of devastation wrought by the world wars and a benefit of the political project for an inclusive and non-antagonistic Europe, but also to the paradigm shifts in the paradigm for armed conflict in the past decades. The functional reintegration of historical defensive structures has therefore become a necessity in all cases, from fortified cities and ancient fortresses to medieval fortresses and reinforced concrete bunkers built throughout the 20th century. Fortified and still inhabited cities pose only questions of good governance and good practice in the maintenance and conservation of the existing built stock7. On the contrary, the only economically plausible alternative for a large proportion of defensive structures, dating from before the Renaissance and preserved in a state of ruin, often as uncovered archaeological remains, is to turn them into a tourist attraction. Their valorization is extremely problematic and, unfortunately, many cases of older and more recent interventions in Romania fail to reconcile the requirements of cultural tourism even with the most basic precepts of the numerous, well-founded international doctrinal documents8.

Fortress

Fortunately, this is not the case with the Oradea Fortress. Having been in use by the army until relatively recently, the buildings were kept in relatively good condition until the ensemble came to the attention of the planners, even if, between 1975 and the restoration intervention, some of them were put to improper use and suffered degradation. Today, its neighborhoods are to a large extent the result of the historical development of the settlement, the spatial and territorial association appearing relatively organic. The exception is the location of the housing blocks from the 1980s, which were interposed between the citadel and the 1 December Park (formerly 23 August), built on the site of the former central square, composed with a well-supported perspective towards the Episcopal Cathedral and the western façade of the fortified ensemble, with which it would otherwise form an exceptional monumental urban space. There is no point here in speculating about a possible 'negative' urban development, which would involve the disappearance of residential blocks. They are an excellent anti-contextual example in that, while the inhabitants of the buildings enjoy privileged views of the park and the citadel, the presence of the massive buildings, located without any trace of interest in the history and urban composition of the place, can only be perceived unfavorably from any direction; they destroy, in the medium and long term, not only the urban landscape but also the use value of the vast open spaces in the middle of which they are enthroned. However, their presence, so inappropriate from the point of view of public space, aesthetics or heritage, provides an opportunity to discuss the presence - which I described above as strange - of the fortress in the midst of the urban fabric, which is in a state of perpetual evolution.

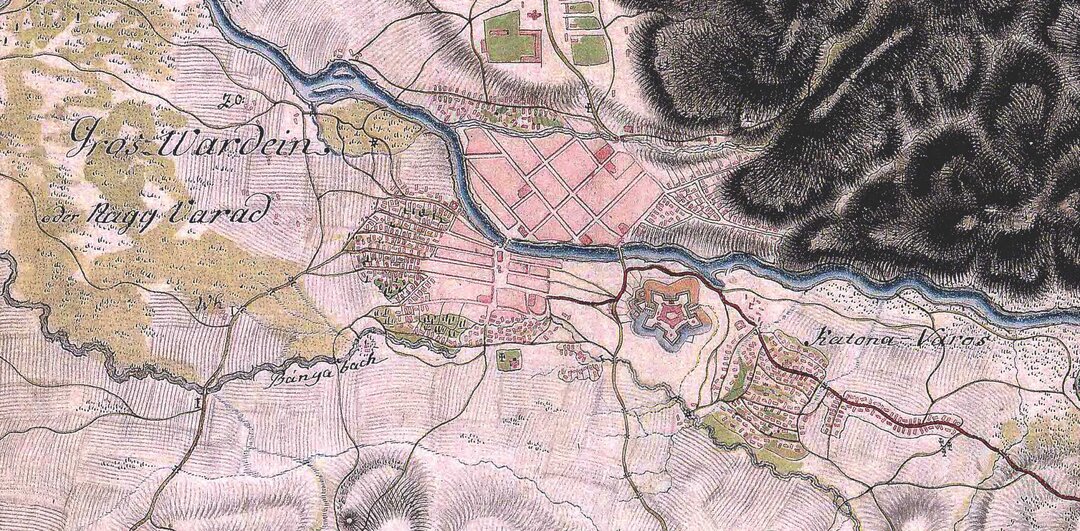

The opposition between the old military structure, which over the centuries has lost all defensive utility but has stubbornly resisted, and the residential blocks, with commerce on the lower levels and comfortable dwellings distributed over the floors (similar only in this respect to the Ullmann Palace, smoothly integrated into the urban fabric), which enjoy every conceivable functional legitimacy, is extremely complex. On the one hand, the city has grown over time, integrating the fortifications into its interior, thus depriving them of the openings (counterscarp, etc.) that could still have been to their advantage in a possible confrontation. On the other hand, the residential function, essential to any settlement, has taken over an open space which (in the past and from a defensive point of view) had been part of the neighborhood of the massive fortress. Exceptionally built forms, dictated by outdated military techniques, are pitted against relatively banal architectural forms of recent date. Social, economic and urban dynamics have changed many times over the past millennium, since the first fortification on this bank of the Criș Repede - the fortress was built progressively between the 11th and 18th centuries until it reached its present form.

Fortress

The possible registers for comparison are so numerous that they run the risk of clouding the fundamental questions: how will the heritage ensemble of the Citadel of Oradea evolve in the post-industrial city? How much longer will the blocks of flats last? Will they, too, be able to be re-evaluated over time, becoming historical monuments? What architectural and urban planning in(ter)ventions could integrate such incompatible assemblages? What will an inclusive and pluralist, conservative-progressive-artistic-artistic-pragmatic-economic-ecological approach to the settlements of the third millennium look like?

*

The change in architectural meanings does not equate with their disappearance, but, on the contrary, with the diversification and semantic enrichment of the built environment. The assumption of heritage values by communities - even if only marginally, as a backdrop for photographs - underpins the hope that we will be able to preserve them over time. And the economic viability of rehabilitating historic structures for current functions is perfectly matched by the imperative need to conserve the planet's resources. For this reason, and in this sense, the preservation of architectural monuments is not a matter of passivism, but a new avant-garde.

NOTES

1.Cf. Gerle János Gerle, Kovács Attila Kovács, Makovecz Imre, A századforduló magyar építészete, Szépirodalmi könyvkiadó, Budapest, 1990, p. 261.

2.Based on the realization that we are the only inhabiting species - in the sense that we alone confer meanings to the territory we occupy, thus converting it into a "place", we have discussed elsewhere the wider meanings of the idea of inhabitation: "Locuirea entre permanent și temporar", in Arhitectura românească în detalii - Locuințe, Emilia Țugui, editor, Ozalid, Bucharest, 2012.

3.The Citadel of Oradea constitutes one of the PIDU projects for the capital of the Crișurilor Region, together with projects to enhance the city's Secessionist heritage (see Gerle János et al, op. cit.) and the rehabilitation of the technical and public infrastructure, cf. PIDU Oradea, published on November 24, 2014, http://www.oradea.ro/politici-si-strategii-ale-municipiului-oradea/planul-ingrat-de-dezvoltare-urbana-a-municipiului-oradea, August 27, 2019.

4.Of course, until very recent times, the fortress was located outside the city, as can be seen, for example, on the military elevation of Josephine (1782-1785) , https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a7/BihorSolnocCrasna_Josephinische_Landesaufnahme, 27.08.2019.

5.In 2018 it had a population of 5,419 and a postcode Cf. https://en. wikipedia.org/wiki/Palmanova#History, 27.08.2019.

6.For the contextualism of defensive structures, see for example Philippe Prost, Vauban: le style de l'intelligence, Archibooks, Paris, 2007.

7.The case of the enclosure walls of the Umbrian city of Norcia is exemplary: partially destroyed by the earthquake in 2016, their restoration has generated a register of questioning that is unprecedented for this kind of built heritage.

8.The Capidava fortress, the Arutela fortress, the Suceva fortress of Suceva, the Deva, Feldioara, Râșnov, Rupea fortresses are just a few of the failed cases of hypothetical reconstruction resulting in historical forgeries. Their discussion is not the subject of these lines.