We lack political will and vision

Thematic dossier

Lack of political will and vision

Interview with architect Ernest PAFKA by Alexandra FLOREA

The architectural work is not finished until the final reception. Sometimes not even then!

What advice? Simple: obey the law!

The architect must have respect for the building he is creating or restoring, but also for the beneficiary.

I say to those who want to make money from restorations: not in Romania!

Even if the building belongs to the owner, the way it looks affects us all.

It's hard to find specialists, and even harder to find free specialists when you need them.

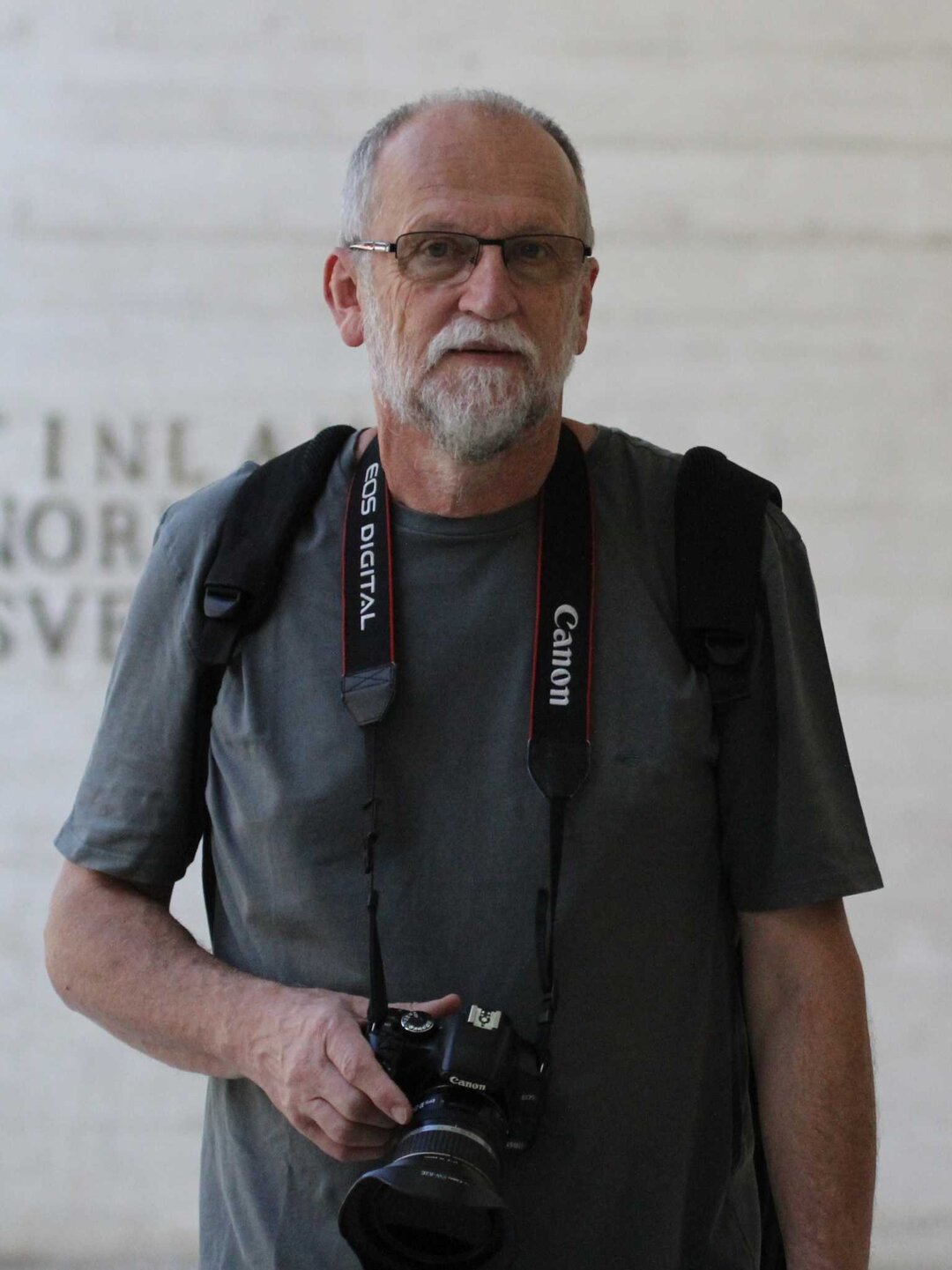

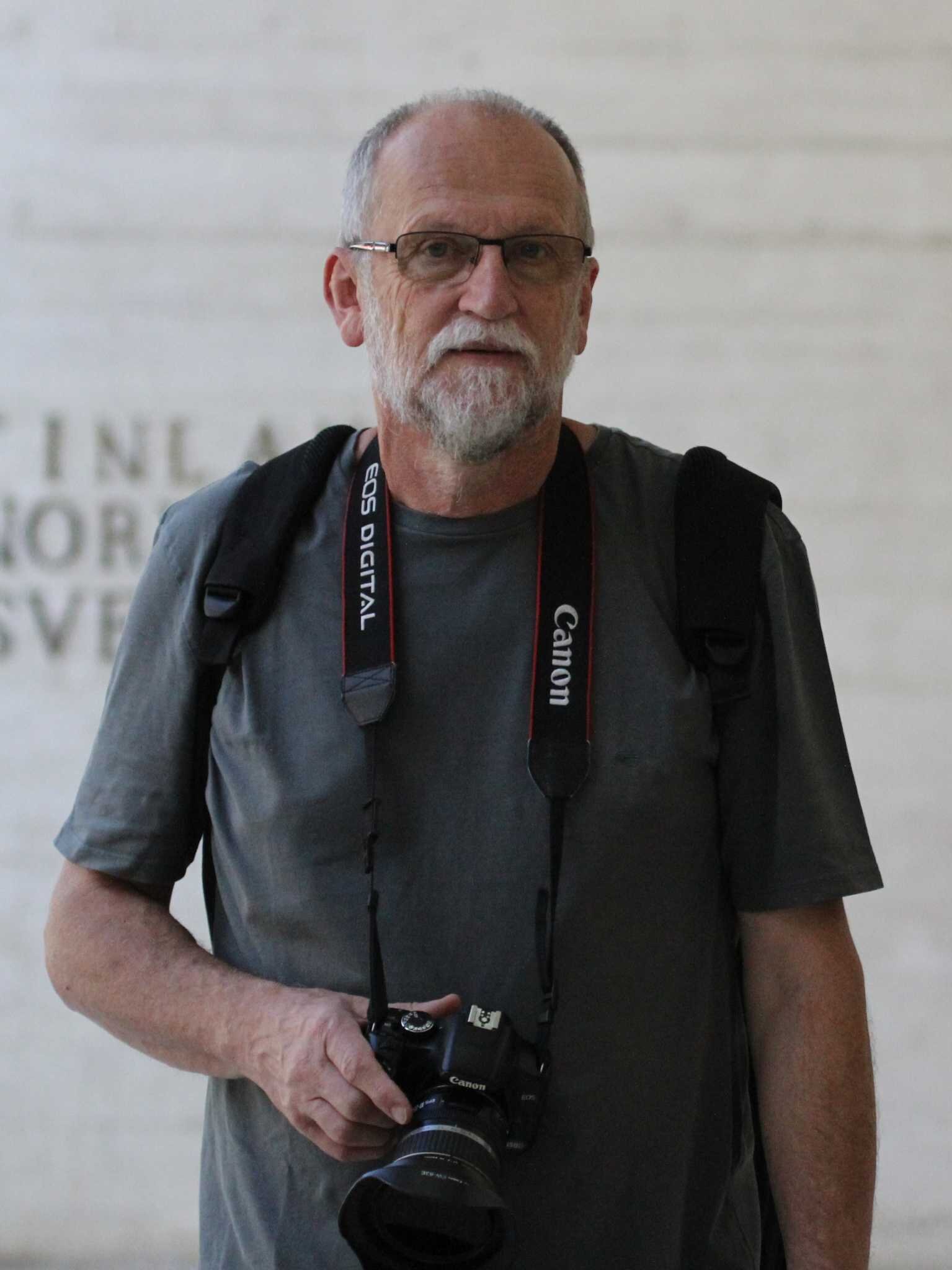

Ernest Pafka has traveled a lot, seen a lot and learned a lot, using all his experience to reinvigorate the civic spirit and space and to create a new approach to buildings and public spaces in the city that adopted him. He is uncompromising, perfectionist, categorical and does not negotiate the quality of the architecture he practices. He does not want to please the authorities, nor his clients or collaborators, because he has no other measure than a job well done, without compromise and without concessions.

Ernest Pafka has traveled a lot, seen a lot and learned a lot, using all his experience to reinvigorate the civic spirit and space and to create a new approach to buildings and public spaces in the city that adopted him. He is uncompromising, perfectionist, categorical and does not negotiate the quality of the architecture he practices. He does not want to please the authorities, nor his clients or collaborators, because he has no other measure than a job well done, without compromise and without concessions.

Ernest Pafka is so passionate about the projects in which he is involved that he does not have time to talk about himself, nor to publicize himself, but everyone who knows him knows that we cannot talk about the architecture of Oradea without talking about him.

We started from the bottom

Alexandra Florea: Mr. architect, you graduated from the Institute of Architecture "Ion Mincu" in Bucharest in 1976. What made you decide to settle in Oradea?

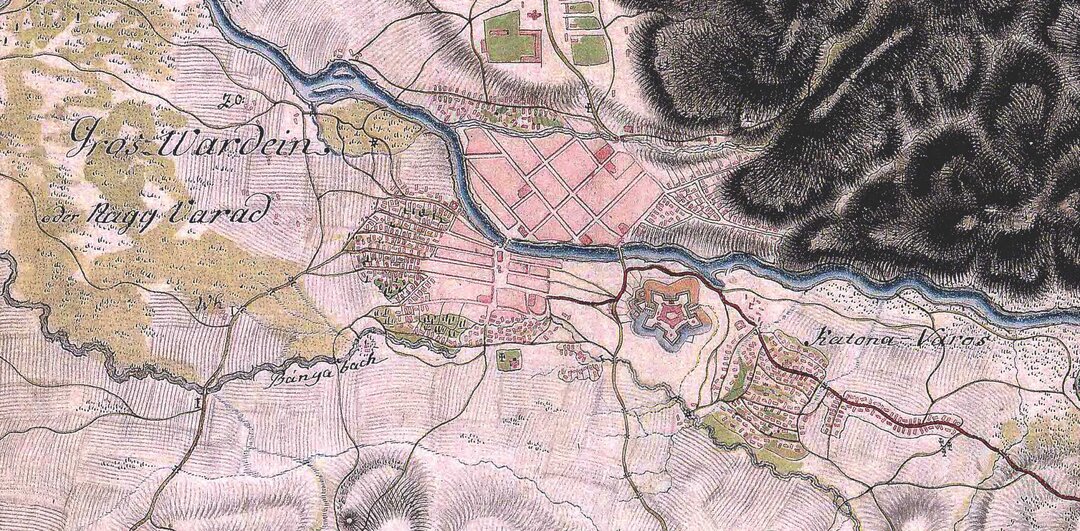

Ernest Pafka: My desire was to settle as far west as possible. I preferred Oradea, the city I have loved since childhood. I liked the atmosphere of the city, its eclectic buildings, the baroque ensemble of the Roman-Catholic Episcopal Palace, the Secession buildings (why have they suddenly become Art Nouveau today?), the banks of the Criș Repede, preferring a "provincial", quiet city. I dreamed of living in one of the city's old buildings and managed (after many years of living in a comfort 2 block) to move into a special building in the city center by the Budapest architect Spiegel Frigyes.

Before '89, I worked, along with all the other architects in the county, at the County Planning Center. I started from the bottom, from a trainee architect and worked my way up to the "position" of head of the architectural team. In 1991, after the Companies Act came into force, my wife and I founded Pro-Arh Ltd. architectural studio, which recently celebrated its 28th anniversary.

In a relatively small city like Oradea, you can't specialize in a particular architectural program, so we have developed very diverse works both in terms of program and scope. In the last 10 years, we have focused on historical monuments and buildings in protected areas.

I had no idea I would be doing restoration

A.F.: How did you come to love restoration?

E.P.: I grew up in a small town in Ineu, in the Crișana region. From the garden we could see the castle of the fortress, and as children we used to play in the moat or on the ruins of the only bastion that was preserved. In high school, when I decided to study architecture, I was shocked by the state in which the buildings of the fortress were (and still are). I don't know whether or not such things influenced my decision to become an architect, but I clearly had no idea that I would be involved in restoration.

A.F.: For this interview, I have chosen three of the most representative buildings in the city of Oradea, rehabilitated or restored by your firm. I will start with the Citadel of Oradea. What did the work on the Citadel consist of?

E.P.: In 2004, we developed a first project for an open-air theater in the Ciunt Bastion of the Citadel of Oradea. Then we had the chance to win (in association with three other design firms) the two projects with European funding for the rehabilitation of the five buildings of the Princely Palace and all the other buildings in the Citadel, including the related technical and public works. At the same time, we also landscaped the park in the moat of the fortress.

A.F.: You played an important role in making the local authorities aware of the importance of the rehabilitation works in the Citadel. What was the state of the Citadel when you started designing it?

E.P.: Under the previous regime, the Fortress of Oradea housed a military unit, the Traffic Police, the National Archives, a bakery and various warehouses. By the time the Citadel became property of the Municipality of Oradea, some of the buildings were already abandoned, partially destroyed, and others had functions that were not suitable for a category A historical monument. While surveying the buildings, we found some of them in a state of disrepair, with many parasitic interventions (BCA walls, plasterboard, concrete floors, cement-based plaster, inappropriate finishes, etc.).

Hard to find specialists, even harder to find free specialists when you need them

A.F.: The Citadel has needed specialist work in different categories, such as restoration, consolidation and securing, conservation. Tell us a bit about these works.

E.P.: The Citadel of Oradea underwent restoration with European funds (20 million euros for the rehabilitation of eight buildings) and from the local budget (3 million lei for the construction of the Summer Theater in the Ciunt Bastion). In view of the complexity of the work, the projects were developed in several phases, with the contribution of numerous specialists. The work started with preventive archaeological surveys, which were finalized with approved reports. The work of the archaeologists continued during the execution of the works, providing ongoing archaeological assistance and research.

In the first design phase, all the constructions were surveyed, art-historical studies, stratigraphic and parament research, moisture surveys, biological surveys of the wood material, and technical surveys of the structural engineering were carried out. The execution designs were based on these studies and, of course, on the design basis prepared by the beneficiary.

Collaboration between the designers and the drafters of the specialized studies continued throughout the design and execution. On site, we revised two projects to incorporate archaeological discoveries made during the execution phase.

©Ernest Pafka

Oradea Fortress is one of the few bastioned fortresses in Romania, representing the emblem of the city and the focal point of cultural events.

Archaeological research has established the location of this first urban center under the present-day footprint of the fortress. The first building was originally erected at the end of the 11th century, on an island situated between the arms of the Criș Repede and Peța rivers, a marshy and wooded area.

In 1619, the Transylvanian prince Gabriel Bethlen began to build a unique palace within the walls of the fortress, with walls parallel to the outer walls of the fortress, with a tower in each of the five corners. The construction was based on a design by the Italian architect Giacoma Resti from Verona. The Princely Palace, unique in Transylvania, was completed in 1650 in late Renaissance style and is considered the most beautiful ensemble of monuments in the Principality.

The moat surrounding the fortress was filled with thermal water from the Peța stream and cold water from the Crișul Repede, with an average depth of 4 m and a width of 50 meters, thus preventing the water from freezing and the fortress from being conquered in winter.

The Princely Palace, through its five buildings - A, B, C, D and E - has been allocated a cultural and museum architectural program, with the Museum of the City of Oradea operating in the A and B buildings.

One of the most beautiful rooms is the Hall with Griffins, which depicts eight mythical and real animals representing the virtues of the princes (bravery, strength, purity, tenacity, endurance, agility, promptness).

"The 'Bread Museum' is housed in Hall H, where a bakery operated for over 300 years. It was built in 1692 under the command of General Corbeli.

A.F.: Among the projects you have realized in the Citadel was the construction of the Summer Theater. How did you integrate its presence in a medieval fortress?

E.P.: The Summer Theater was set up in the Ciunt Bastion and in the courtyard. The public functions - lobby, box office, stage entrances, a café - were located in the courtyard rooms, while the functions attached to the stage - actors' dressing rooms, toilets, scenery storage - were located under the stage and under the bleachers. Above is an amphitheater with a maximum seating capacity of 800. The steps are made of natural stone masonry, covered with wooden benches, the walkways are clinker brick and the access road is made of cubic stone. Interventions in the Ciunt Bastion, other than those strictly necessary for the construction of the amphitheatre, consisted in demolishing the foundations and parasitic masonry dating from the 19th-20th centuries, redeveloping the roundabout road around the perimeter of the bastion, highlighting the medieval walls discovered during archaeological excavations and landscaping the resulting slopes. At the same time, conservation and restoration works were carried out on the bastion walls, including completing the brickwork of the masonry with old-type bricks, completing the perimeter coping of the bastion parapet and paving the roundabout road with klinker bricks.

A.F.: In 2015, you also worked on the setting up of an archaeological park in the citadel, near the

Roman Catholic Church and the Princely Palace. How did you choose to highlight the presence of these buildings? How did you highlight the tombs of Kings Sigismund of Luxembourg and Ladislaus I of Hungary?

E.P.: In the context of the archaeological discoveries in the basements of buildings A and B and in order to enhance their value, it was necessary to continue the archaeological research in the courtyard of the Princely Palace and to enhance the cathedral remains. Following the preventive archaeological survey, the interior courtyard of the Princely Palace was also landscaped, with the 14th-century Gothic cathedral walls marked on the ground, and two (of the seven documented) tombs of the royal heads buried in the cathedral marked in situ: that of the King of Hungary, St. Ladislaus I (Szent László), the founder and patron of the city, and that of the King of Hungary and Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg, the only Romano-German emperor buried outside the borders of his kingdom.

The design of the inner courtyard of the Princely Palace has emphasized the constructive elements of the Gothic cathedral and the adjacent buildings, reconstructed according to the results of archaeological research. The walls have been marked with cut stone. The surfaces inside and around the cathedral are finished with compacted gravel for future research. The perimeter space was clad with cubic stone, as it will not be archaeologically excavated in the future. Around the trees we created small green spaces. The vaults in which the kings were buried are marked in the plane of the courtyard pavement with klinker bricks; the tombstone is made of Rosso Verona marble and white Carrara marble.

Regina Maria Theater

The State Theatre marked the center of gravity of the architectural configuration of late 19th century Oradea. In February 1894 a theater commission launched a public tender for the design of the building. Only two designs were submitted, but none of them lived up to the vision. In March 1895, the renowned Viennese firm "Fellner & Helmer" was commissioned to design the theater. The city's chief engineer decided to consult with the Viennese firm, and the chosen location was Bémer Square (Ferdinand Square).

Seeing that financial problems might block the project, architect Kálmán Rimanóczy Jr. undertook to erect another building - today's bazaar - next to the theater building, using building material salvaged from demolition, to generate extra income for the city from renting it out.

The first pick was hammered into the foundations of the theater on July 11, 1899, and the inauguration of the cultural center took place on October 15, 1900. The theater was erected in 15 months under the supervision of the team of architects Rimanóczy Kálmán Jr., Rendes Vilmos and Guttmann József, and the city's chief architect David Busch. The building marked the high note of classically dominated eclecticism in the city's architecture.

The auditorium is spread over three levels, originally seating up to 1,000 people, of which 740 were seated. The lighting of the interior spaces was provided from the beginning by electricity, which had not yet been introduced throughout the city, and most of the public spaces were lit by gas.

In the periods 1900-1919 and 1940-1944, the theater was called Szigligeti Ede - Hungarian playwright (1814-1872) who lived in Oradea.

Between 1919-1940 the theater was called Regina Maria.

In 1928 the Romanian troupe of the Western Theater was founded.

In 1945, it was renamed the State Theatre of Oradea, in which two independent Romanian - Regina Maria and Hungarian - Szigligeti Szinház - theater companies operated.

A.F.: Another large-scale work you have been involved in was the State Theater, also known as the Regina Maria Theater, which is one of the most important cultural landmarks of Oradea. What work was involved in the renovation project and what did the documentation work entail? How did you find your information?

E.P.: The building of the State Theater of Oradea is a Historical Monument category A, dating from 1899-1900. Fortunately, I found enough documentation about the history of the building and even some original plans. The building was designed by architects Fellner&Helmer and arch. Helmer Hermann and was realized in 15 months in association with three contractors from Oradea: Rimanóczy Kálmán, Guttman József and Rendes Vilmos. The style of the building is eclectic, with neoclassical elements, and the interior (lobby and performance hall) is decorated in Baroque style. The allegorical sculptures on the facades and the interior decorations were executed by Peller Ferenc (sculptor from Oradea - painting and gold leaf decorations), Eichorn Vilmos (ornaments, plasterwork), Linhard Vilmos, Kuncz Jozsef & Associates (tapestry work), Reiner Karoly (furniture) and Herczegh Vilmos. The furniture was made by Thonet - Budapest factory. The chairs with self-adjustable (on the ground floor) or fixed (in the lofts and on the second floor) seats are upholstered with red plush. Few buildings could be as well documented as this building! Compared to the 15 months in which the building was realized, its rehabilitation (design and execution) took over 5 years. The whole work can be considered historic restoration. We did not have to intervene with new architectural elements, fortunately, neither in the building nor on the facades, where the original decorative elements have been preserved.

I have been thinking a lot about the two architects, about what it means to have the will, to work in an organized way and to be supported by the whole community. I think today we lack the political will, the vision to organize something in the chaos we are in.

[caption id="" align="alignleft" width="158"] ©Ernest Pafka[/caption]

©Ernest Pafka[/caption]A.F.: What was the condition of the theater building at the time of the interventions?

E.P.: The building was permanently maintained, without parasitic interventions. The most damaged parts of the façades were the weatherstripping, gutters and attics. The carpentry was in a state of disrepair beyond repair. The plaster in the field was redone and all plaster and plaster parietal decorations of the facades were repaired. The exterior woodwork was replaced with wood joinery, respecting the form and decoration of the original. On the basis of existing photo-documentation, the allegorical high-relief allegorical reliefs on the pediment, removed in 1922, were restored. The decorative light fittings on the facades were restored on the basis of a single surviving original. There were four decorative cast-iron lamp-posts in front of the building, of which only one has survived. The others were rebuilt according to the preserved original.

A.F.: Did the proposed intervention fall into the category of a historical restoration, going off the pastiche, or was the intervention emphasized so that it would be visible to new generations?

E.P.: The work as a whole is not a reconstruction in style. All the existing decorative elements have been restored and only some missing secondary elements have been "exactly" restored. All wall and ceiling decorations have been preserved (in good or mediocre condition) and were restorable. There were 24 different lighting fixtures in the building, which still exist today, most of them functioning properly. We felt that it was necessary to "exactly" reproduce those that had disappeared. Thanks to new glassmaking technologies, the new fixtures can only be distinguished from the old ones on close inspection. This work was a challenge because of its complexity. After redoing the electrical, plumbing and heating installations, the restoration of finishes, decorations and furniture followed.

The terazzo work consisted of repairing the floors in the corridors, stripping and re-laying the decorative floor in the ground floor hallway. In the upstairs hallway we preferred to keep the terazzo floor in its original state and to cover it with a carpet made to order in Germany, which exactly reproduced the floor decorations.

The preserved masks, appliqués, ornamental and ventilation grilles were repaired (degreasing, sanding, cleaning with sandpaper and hydrochloric acid, sanding, sanding again, and isolation), and the missing ones were reproduced as they were in the original.

The ornamental plaster carvings and all the wall and ceiling decorations were restored (cleaning, wiping, volume additions, remodeling with modeling plaster, hand sanding, painting, partial covering with a layer of gold leaf, protective insulation).

The interior woodwork was preserved and repaired, and the shingles, clangs, mirrors, and box pegs in the lofts were refurbished or completed. The lobbies' wallpaper, central and side curtains, window curtains, and the auditorium carpeting were redone, all custom-made to the original patterns and colors.

The chairs and armchairs in the auditorium and boxes (which were no longer the original ones) were dismantled and new chairs and armchairs were made according to the model of the Budapest Comedy Theater (also designed by Fellner&Helmer), very close to the original ones in Oradea, with larger gauges than the original ones, in compliance with current standards. The restoration work was completed in 2011, 111 years after the building was inaugurated.

Town hall

The problem of building a new Town Hall was posed as early as 1860, after the unification of the four component fairs of the city, on the site of the Episcopal Palace in the New Town. The site was chosen by the city's chief engineer, Busch David.

The City Council launched a competition for the design of the new building, with a deadline of March 31, 1896. Nine designs were submitted, of which four were purchased - Rimanóczy Kálmán Kálmán Jr., Hübner Jenó, Jaumann Benedek and Láng Adolf. The City Council decided that Rimanóczy Kálmán Jr. would draw up new documentation on the basis of the four projects, which would be made available to the City Council free of charge. Rimanóczy was also awarded the contract. Demolition of the former residence began on October 21, 1901, and the building was constructed between 1902 and 1903.

The builder was Sztarill Ferenc Ferenc, who had originally proposed that the Town Hall should be located on the site of the Eagle Inn. The inauguration took place in January 1904, when Rimler Károly, the longest-serving mayor in the city's history - June 1901-June 1919 - was in office.

The architectural composition is organized around three inner courtyards and the building covers an area of 5,508 square meters. The main façade and the one facing the Criș are the most spectacular. The building gets the neoclassical style.

The clock tower is 50 meters high and was equipped with a watch room for the city's fireman on duty. On the first level of the tower is the clock mechanism, known as the "mother clock". The clock at the highest level plays the "March of Iancu" at fixed hours and was built at the beginning of the 20th century.

The architect must have respect for the building he creates

A.F.: Looking to the future, you are starting work on the Town Hall. Tell us a little bit about what the refurbishment work entails and how you came to be in charge of this project.

E.P.: If the design-execution work on the theater took 5 years, the Oradea City Hall building has undergone three different interventions.

The first project, carried out in 1997, consisted of capital repairs to the facades of the building (plastering, painting, repairs to the decorations), basically a conservation and repair work on the plastering and decorations and a repointing of the facades.

The second stage, planned in 2009 and carried out in 2011, consisted in extending the building by covering an interior courtyard. Thus, a 500 square meter hall was built on the ground floor - a lobby for counters and public relations - and a 500 square meter dining room for the institution's staff on the basement floor.

A public reception area was created by building a reinforced concrete floor on the existing ground floor. A metal structure floor, supported on perimeter pillars and fitted with glass skylights, was built over the hall. On two sides of the hall, light courtyards were provided to provide natural lighting and ventilation to some basement and ground floor rooms. It was proposed to lower the height of the inner courtyard to the basement level and to extend it with new functions - cafeteria and restrooms.

Public access to the lobby with counters was provided from the two sides of the ground floor corridor on either side of the central stairwell, through doors created by removing the existing window parapets.

Also at this stage, the interior of the Clock Tower was rehabilitated to create a Tower Museum, a first step towards introducing the Town Hall building into the tourist circuit.

The third and most complex work was carried out in 2018, following a competition. The aim of the work was the rehabilitation, restoration, consolidation and introduction into the tourist circuit of the Oradea City Hall building, with the beneficiary requesting the development of spaces for tourist use in the wing facing Unirii Square.

The work foresees the repair and partial restoration of the terazzo floors in the lobby and corridors area, the restoration of the original wall and ceiling decorations in the respective area of the building, based on the existing ones, the rehabilitation of the interior carpentry, the restoration of the floors in the council hall and the small meeting room, including the flooring infrastructure. It was also requested to: restore the boardroom to its original form and strengthen its roof; change the current furnishings in the auditorium to similar 1903 furniture with leather upholstered benches and desks, based on photo-documentary information and similar works of the period. The project also envisages the restoration of the original roof of the building to its original shape on the wing facing Union Square - the central part, the side wings and the rehabilitation of the building's facades.

Even if the building belongs to the owner, the way it looks affects us all

©Alexandra Florea

A.F.: You have been and are still involved in the city's problems. You are uncompromising and categorical when it comes to heritage. The restoration of the facades of the historic center of Oradea has become a national reference. How do you see this program and its results?

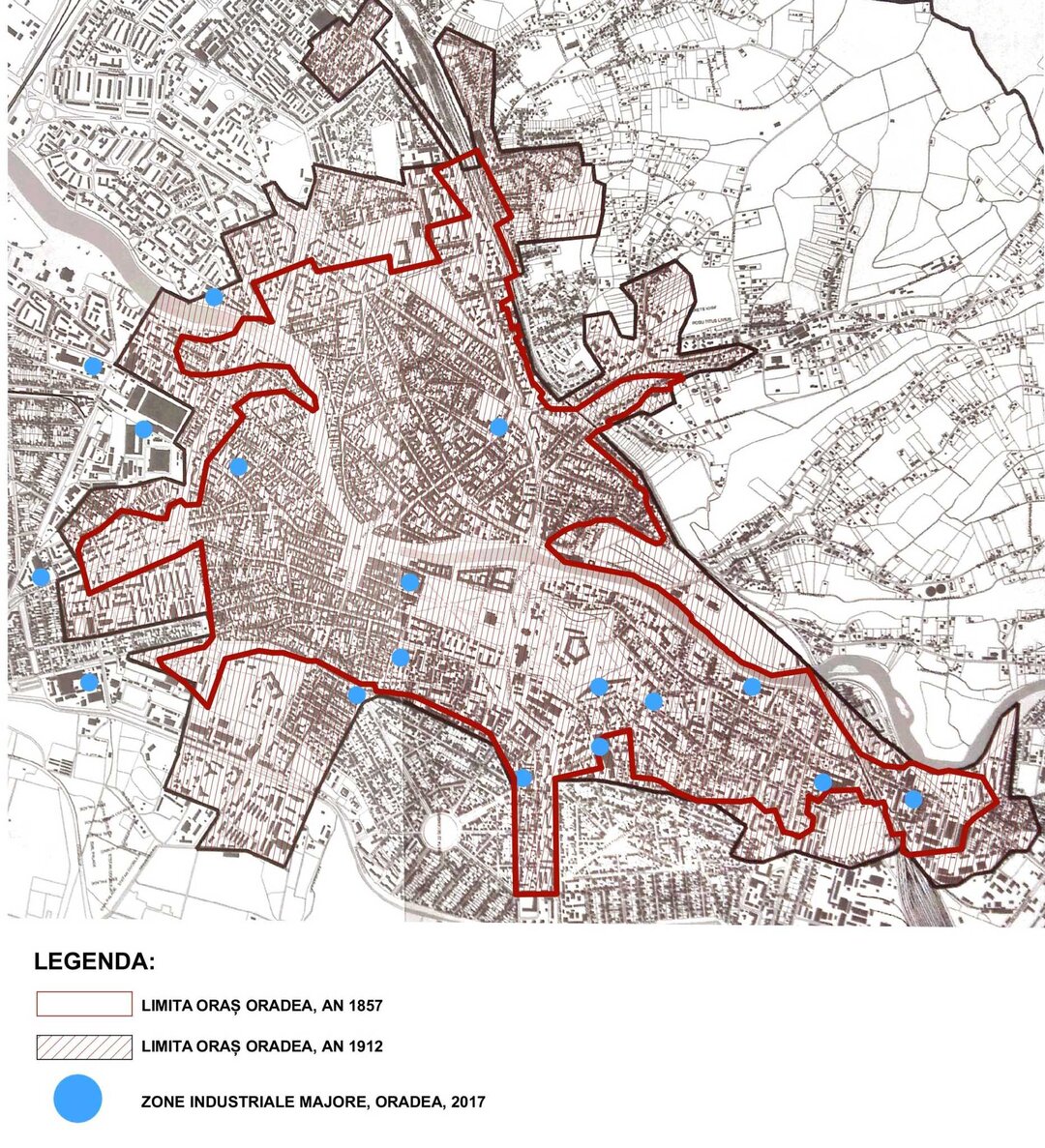

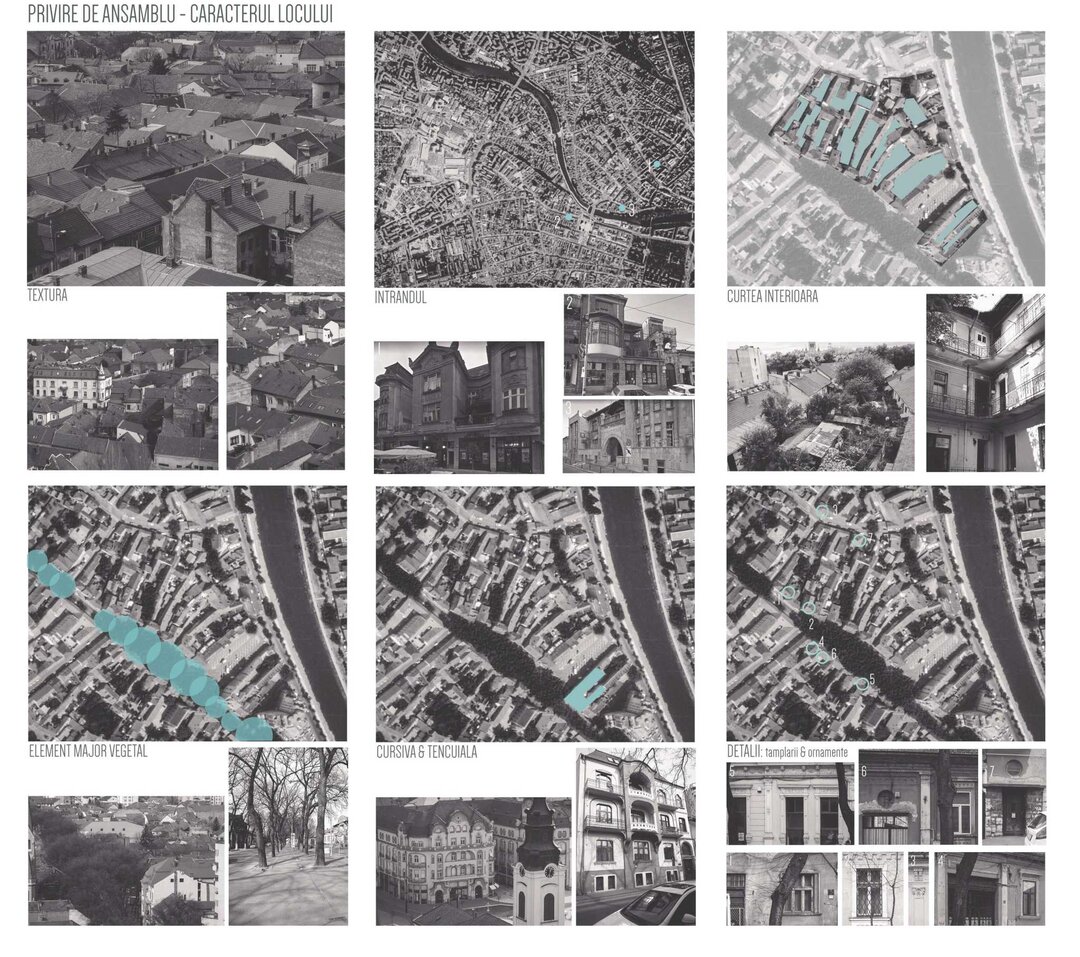

E.P.: You know what happens, even if the building belongs to the owner, the way it looks affects us all. Oradea is one of the most beautiful cities in Romania from an architectural point of view. We have buildings in baroque, classic, eclectic or Secession style. Right after the Revolution, these monuments came into the possession of people who didn't know how to appreciate them and didn't learn to appreciate them. How did this happen? Something had to be done, because there were many projects to rehabilitate the facades, but they didn't work. We tried to solve the facade problem with a pilot project based on an evidence-based analysis of all the important buildings in the municipality.

The study was carried out by our company. There is a great need for this study, because we live in a wonderful city with many monuments, but poorly maintained. Of the 1,800 buildings we studied, only 5-6% were properly maintained. Most of them were not properly maintained in the years after the Revolution. The owners were courted by merchants of plasterboard, PVC, paint or thermopane and spoiled the original architecture of the buildings. Many of the parts that have become shops, offices or ABCs, have broken walls, rebuilt or altered certain elements of the buildings. The stained-glass windows have disappeared, they were sold at knock-down prices by the owners who bought the buildings for a pittance immediately after the Revolution and now we see those stained-glass windows in the West. The portals have disappeared and now we have hundreds of houses that are no longer symmetrical. White PVC joinery has been put in because it's the cheapest, without any thought for the architecture or the color scheme of the buildings. There has been a lot of bad attic work, a lot of bad taste, with shapes suitable for a mountain house, not for eclectic or Secession architecture.

We made a file for each individual building and a list of buildings proposed for protection: protected facades, buildings proposed for classification, which interventions are possible and which are forbidden. We have established a color palette for each street so that the area has a unified look. There should be a heritage damage fee based on these criteria, and if the owners do not want to take advantage of the renovation bids, they will have to pay this fee. It would be a timely way to get owners interested in renovating their buildings. Only in this way can the appearance of the city change.

A.F.: How was the collaboration with specialists from the other fields involved, as a multidisciplinary approach is crucial in a restoration of this scale?

E.P.: In general, we managed to have a fairly good collaboration with the specialists we were able to contact. The problem is that, in many fields, it is difficult to find specialists and even more difficult to find free specialists when you need them. For this reason, the general designer's deadlines often have to be reconsidered. In this case, there was no need.

A.F.: You said it's hard to find skilled craftsmen these days. Did you encounter difficulties in finding a team of craftsmen who could successfully honor this intervention?

E.P.: For the first two interventions on the Town Hall building, we had good cooperation with the contractors - they had or hired good craftsmen. For the third work, which started in August, I can only hope that we won't have any problems.

A.F.: What is your "soul" building so far and what fascinated you about it?

E.P.: Always the last one I work on. Of the three works mentioned in this interview: The Fortress is the largest work and with the most modifications (to the advantage of the monument) during the execution; The Theater Building was the most complex in execution and with satisfactions due to the quality of execution; The Town Hall Building is the most interesting, due to the possibilities of regeneration, integration of a new function, the possibility of recovering the monument for contemporaneity.

The architectural work is not finished until the final reception. Sometimes... not even then!

A.F.: Do you think architects have to have a special moral profile? What would that be?

E.P.: I believe that the architect must have respect for the building he is creating or restoring, but also for the client. The realization of the project must be done with seriousness, in close communication with the specialists with whom he collaborates to complete a multidisciplinary project. And, last but not least, it is very important to follow up the work during execution and to resolve any problems quickly. The work is not finished until acceptance. Sometimes... not even then.

A.F.: Are there common principles that apply to all your projects?

E.P.: I believe that each project is different and should be approached as such, even if the basic design principles are the same. In the case of restoration works or interventions on a monument, the work must start with thorough and serious documentation and a complete survey (technology helps us). We have always tried to work as closely as possible with the specialists, the beneficiary and the contractor. I admit that we have not always succeeded. We are optimistic, we keep trying.

What advice? Simple: obey the law!

A.F.: Do you have any advice for the residents of Oradea (I mean the owners of historic buildings) regarding architectural restoration?

E.P.: I would like to answer a little differently. In Oradea, on the basis of the "Udrea Law" (it sounds terrible!), there is a program initiated and run by the City Hall, concerning the rehabilitation of the facades of buildings located in the historic center, which includes buildings privately owned by individuals or legal entities. Multiple financial and organizational facilities are offered to owners. Many owners try to modify the project to the detriment of quality, do not want to dismantle their "thermopane", only want to paint the facades without repainting or repairing the plaster, change the color proposed by the architect, etc. In fact, they would like the City Hall to rehabilitate their facades at its own expense. What advice? Simple: respect the law!

A.F.: Do you have any advice for young architects who want to pursue a career in restoration?

E.P.: For those who are complacent and are content to be mere draughtsmen of the beneficiaries' ideas: don't start or give up... For those who want to do it for the money: not in Romania!

For the serious ones: patience and hard work, practice in companies with serious works, collaboration with specialists, seriousness, interest, presence on site, no compromises.