Bucureștiul situaționist. „Ne-am plictisit în oraș, nu mai există niciun Templu al Soarelui”

SITUATIONIST BUCHAREST,

“We are bored in the city, there is no longer any Temple of the Sun”1

| Sunt străin acestui oraș. Îl cunosc doar prin priviri intermitente ce niciodată nu dăinuie mai mult decât intervalul de timp cuprins între zori și amurg. Asemenea oricărui turist, intru în rezonanță cu ritmurile lui mai degrabă prin impresiile și sentimentele pe care le transmite. |

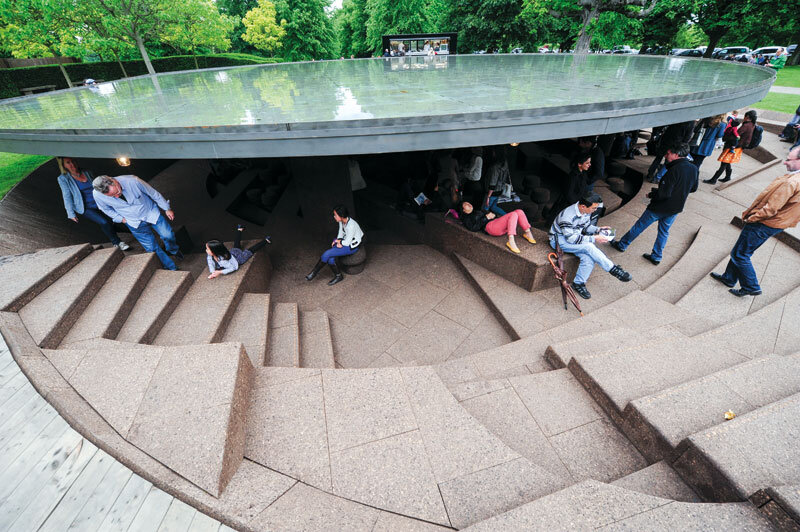

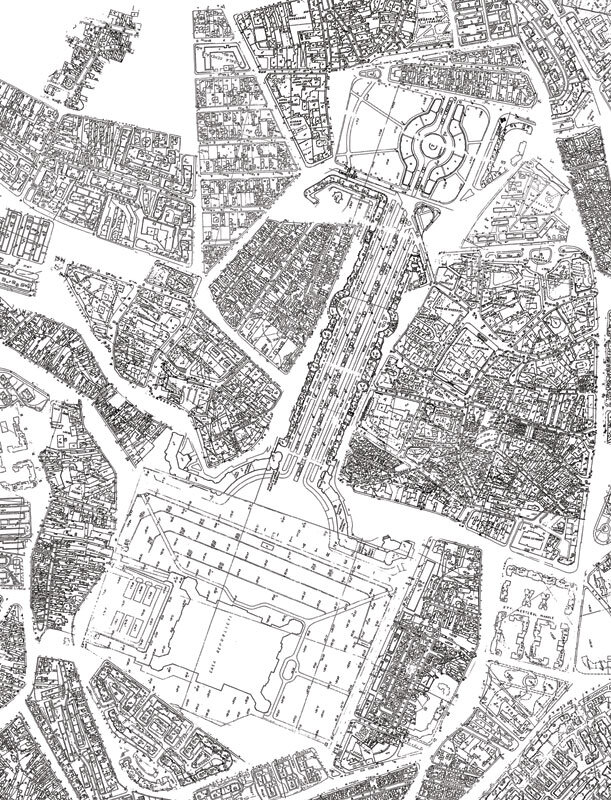

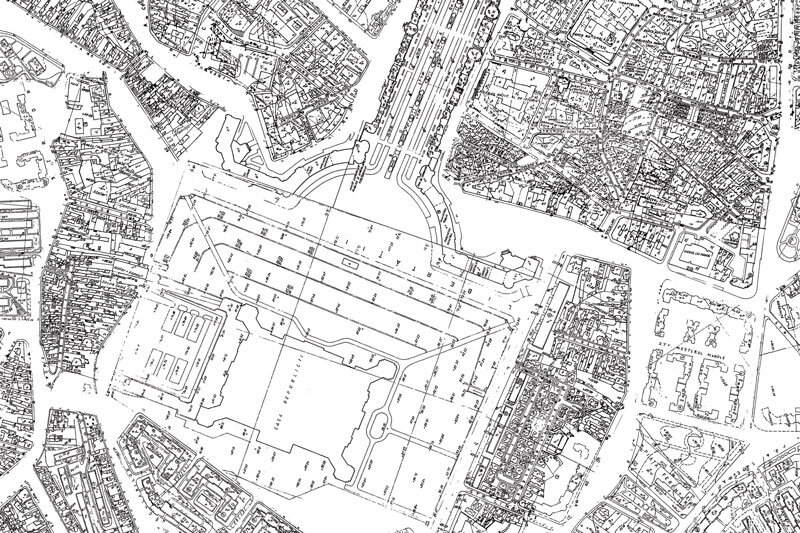

| Nu pretind că am cunoștințe exhaustive despre istoria sau locuitorii lui. Întrucât toate incursiunile mele în acest tărâm sunt motivate de întruniri de afaceri care niciodată nu-mi ocupă mai mult de două ore din ziua respectivă, rămân cu zece ore în care pot să „articulez timpul cu spațiul”2. La fel ca orice situaționist respectabil, hoinăresc prin oraș, încercând să înțeleg mai bine această mașinărie străină și complexă. Pentru mine - venind dintr-o cultură care din fire este îndepărtată, în toate sensurile, de Capitală - Bucureștiul exercită o atracție ciudată, un amestec de curiozitate și frică, care te îndeamnă ba să explorezi, ba să cauți adăpostul unui teren mai cunoscut.În ultima mea incursiune, hoinărind împreună cu un bun prieten, istoric al locului, care întotdeauna are amabilitatea de a-mi face pe plac și de a-mi da lămuriri despre moștenirea orașului, am fost copleșit de sentimentul straniu că mă plimb, de fapt, printr-o enormă distopie situaționistă construită. Cutreierând prin diferitele lui cartiere și atmosfere, am perceput acestă hoinăreală ca pe o recitire a manifestului situaționist din 1953 al lui Ivan Chtcheglov, „Formule pentru un nou urbanism”.

„Toate orașele sunt geologice. Nu poți face trei pași fără să te întâlnești cu stafii care poartă tot prestigiul legendelor sale. Ne mișcăm într-un peisaj închis, ale cărui puncte de reper ne trag mereu spre trecut. Anumite unghiuri schimbătoare, anumite perspective care se de-părtează ne îngăduie să întrezărim concepții originale ale spațiului, însă această vedere rămâne fragmentară. Trebuie căutată în locurile fermecate ale basmelor și ale scrierilor su-prarealiste: castele, ziduri nesfârșite, baruri mici, uitate, peșteri uriașe, oglinzi de cazinou”.3 |

| Citiți textul integral în nr 3/2012 al revistei Arhitectura. |

| NOTE:1. Ivan Chtcheglov, „Formulary for a New Urbanism“, în The Situationists and the City, London, 2009 Verso Books, ed. Tom McDonough, prima apariție în Internationale situationiste nr. 1 (iunie 1958)

2. Ivan Chtcheglov, op. cit. Chtcheglov definește experiența arhitecturală ca fiind o articulare a timpului și a spațiului. 3. Ivan Chtcheglov, op. cit. |

| I am a stranger to this city. I know it only through periodical glimpses, which never last more the fraction of time that usually spans dawn and dusk. Like any other tourist, I resonate with its rhythms mainly through the impressions and emotions it conveys. |

| I do not pretend to actually have any exhaustive knowledge of its history or its people. Since almost all of my incursions into this realm are motivated by business meetings that never take up more than two hours of my day, I am left with another ten in which I can “articulate time and space”2. So, like any self-respecting situationist, I drift aimlessly through the city, trying better to understand this foreign and complex machine. For me, coming from a culture that is by nature far from the capital in every sense, Bucharest exerts a strange attraction, a combination of curiosity and fear, which either stimulates one’s need to explore or to take shelter and retreat back onto more familiar ground.Lately, as I was drifting around with a good friend of mine, a local historian, who is always kind enough to indulge me for a few hours and enlighten me on the heritage of the city, I was somehow transfixed by this strange feeling that I was actually walking in a built situationist dystopia. Wandering through its different quarters and atmospheres I perceived this as a rereading of Ivan Chtcheglov’s 1953 situationist manifesto, “Formulary for a New Urbanism”.

“All cities are geological. You can’t take three steps without encountering ghosts bearing all the prestige of their legends. We move within a closed landscape whose land-marks constantly draw us toward the past. Certain shifting angles, certain receding perspectives, allow us to glimpse original conceptions of space, but this vision remains fragmentary. It must be sought in the magical locales of fairy tales and surrealist writings: castles, endless walls, little forgotten bars, mammoth caverns, casino mirrors.”3 |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |

| NOTES:1. Ivan Chtcheglov, “Formulary for a New Urbanism” in The Situationists and the City, London, 2009 Verso Books, edited by Tom McDonough, first published in Internationale situationiste no. 1 (June 1958).

2. Ivan Chtcheglov, op.cit. Chtcheglov defines the experience of architecture as an articulation of time and space. 3. Ivan Chtcheglov, op.cit. |