Micro and mega architecture

Architecture at maximum (and minimum)

Big?

An article in Le Monde (April 19, 2005, p. 27) talks about the status - marketable or not - of ancient Greek monuments. The dispute is of less interest here. Much more interesting are two clues that the article provides us with about, reborn, the contemporary world's desire to familiarize itself with classicism, in sections of it that are, after all, unfamiliar. The first clue tells us of Vodafone's desire to host a dinner for 150 of its leaders in the portico of Attalos in the Athenian Agora. The second clue tells us about Rhodes and the island's mayor's greatest wish, finally realizable thanks to a coincidence. At stake is no more and no less than the reconstruction of the colossus of Rhodes, which collapsed in 227 BC following an extremely violent earthquake. A blockbuster movie by Elie Choraqui's O, Jerusalem, due to be filmed there, has reopened the debate about rebuilding the disaster of more than two millennia ago. The mayor's arguments are sound and have as much to do with local identity as tourist attraction: it is one thing to take a ferry into a Greek harbor and quite another to do it under the feet of a colossus that was, in its time, one of the wonders of the ancient world.

So we have two cases: an ancient monument that exists, or, what is more, has just been restored, and is being sought as a topos for a dinner party; and then we have the case of a monument whose existence is known for certain, both from texts and from underwater archaeology, but whose absence seems to date from 'yesterday' and should therefore be reconstructed. In both cases we are dealing, for different reasons, with the same relationship of temporal and spatial 'intimacy' with the ancient monument, which can be subjected to the immediacy of ordinary everyday actions: sheltering in order to nourish and repairing in order to re-confer symbolic status to a community.

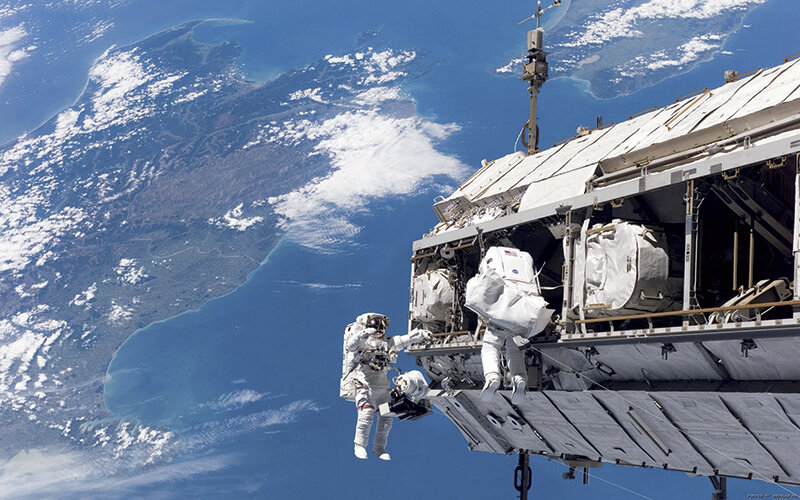

But the strangest relation to the past was also proposed to us by Greece, not so long ago, if we are to judge by the standards of what 'yesterday' means there. In order to explain the significance of the contemporary gesture, we must, in our turn, go back in time to "yesterday" and read the introduction to one of Vitruvius' architectural books, in which the character Deinocrates appears. But until then, a brief detour. Architecture envelops the being and, like the garment, is most often "tailor-made" to fit the person inside: god, if it is a temple, and man, if it is a dwelling. Measure is a key word here. Can you imagine a house for the god? - Ask then to show this: cyclopean masonry, holy of holies, measurelessness and dark absence. At other times, the hippethyric temple (without ceiling and roof), Vitruvius tells us, is for the lords of light and of heaven in general, where the cella remains open, for the godly eye to behold itself. Be that as it may, the scale of the altars must be kept in mind: 'for Jupiter and all the other heavenly gods, let them be as high as possible. For Vesta and for the gods of the Earth and the Sea let them be placed lower" (Vitruvius, IV,9: 3-4), so that the god is reflected in the image of his house. This appropriateness of the scale of architecture to its purpose - the 'absolute measure' (Michelis: 1982, 208) - has to do with the measures of the being/body within. But such projects are not the recipe for monstrosity, but the anthropomorphization of the landscape itself, an even more violent hybris. This terraforming - the taking in the desert, the turning upside down of making, here seen as incomplete - has perhaps its most illuminating example in the vision of Deinocrates. He proposed to Alexander that Alexander should sculpt Mount Athos in the form of a statue holding a city on the left and a bowl on the right in which all the waters of the mountain had collected. Such a vision is called by Oechslin, paraphrasing Josef Ponten in his Architektur die nicht gebaut wurde (1925), a "monstrous idea in Babylonian, colossal in Oriental style" (1993: 473). It has generated the most diverse interpretations, from Philarete and Alberti to Fischer von Erlach. A kind of partial, disfigured fulfillment of it can be seen in the colossus of Rhodos, the statues of presidents carved in Mount Rushmore, the Palace of the Soviets and the Volga-Don Canal, with the Stalinist giants overseeing the terraforming of the USSR through the forced labor of political prisoners. We have in Dinocrates' idea an original example of the giganticism that permeates architecture from time to time. Are they paranoid forms of anthropomorphism, or residues of a time when the earth was inhabited by giants, themselves an abortive project of humanity? Perhaps we need to re-read Rem Koolhas's five theorems on Bigness to understand how far conceptually the over-dimensioning of architecture has gone, which thus enters the aesthetic regime of the sublime (where, incidentally, had Hegel sent it, with the pyramids as an example?)

Here is the fragment of the Vitruvian text in which the voice of Dinocrates breathes: "For I have planned to carve Mount Athos in the likeness of a statue of a man, placing in his left hand the walls of a huge city, and in his right hand a basin to receive the water of all the rivers of this mountain, so that it may flow into the sea." Vitruvius (II, Preface, 2). From the perspective of the face-body/architecture relationship, gigantism and limitlessness usually declares the will to power to be represented by non-human edifices. Alexander declined Deinocrates' proposal, but his followers will be more wary of similar proposals, had they not challenged them themselves.

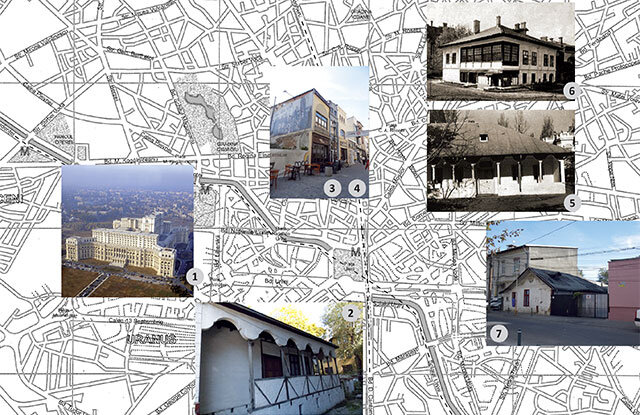

Now here is the news published by România literară (October 41/16-22, 2002): "A Greek-American foundation has initiated a project to carve a gigantic portrait of Alexander the Great into the side of a mountain in northern Greece. According to its promoters, the 80-metre-high, 57-metre-wide sculpture would "strengthen the Greek character of Macedonia" and attract tourists (the project, which will cost about 30 million euros, will include a museum, an amphitheatre and a car park).The Hellenic version of Mount Rushmore has got official approval, but not everyone is happy (...) archaeologists and environmentalists consider it monstrous and are threatening to take it to court.

Small?

To begin with, and unrelated to what follows, I send you to read for yourselves a delightful story about dwarfism from Turkey: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/07/garden/cat-bowl-size-gardens.html?smid=fb-share.

When you're ready, here's another story of sacred spaces from India. Architect Sameep Padera has, for weekends when he gets out of Mumbai, a modest farmhouse at Wadeshwar, a Hindu village 70km outside the city. It's probably a country house with a bit of a courtyard. Of course, local priests have come to ask for donations for a temple dedicated to Shiva. In the good tradition of the architects involved, Padera responds that he's not giving money, but is contributing the design and the time needed to bring it to fruition. The site is beautiful, a wooded expanse by a lake. There's some stone donated from a local quarry. There's some wood. There should be a prayer hall and a sacred room, a room of the god. How do you proceed when you have nothing but a wonderful mind and a history of sacred architecture at your disposal? Simple. Padera reasoned: the waiting room would be a tree grove/assembly hall set up in the woods facing the lake. The holy of holies is built in a traditional form, but only in overall geometry, from existing stone. The architect says he wanted to give the impression that the tower of this sacred chamber had been discovered ruined and had been rebuilt.

Absolute attention is given to the entrance(a threshold device, the architect calls it), which is clad with the wood resulting from the clearing (from the establishment of the temple-like courtyard). All attention and meticulous care and attention is given to the interior of this sacred cubic. In an oriented niche - the statue of the god. In the center of the square plane - a lingam coiled by a metal serpent yoni (symbols of the reunited principles, masculine-into-feminine). The lingam penetrating the yoni snake sits in a stone bowl with water, where offerings (flowers) are placed. A bronze bell is also present. At the statue, incense is burning. Water from the fountain flows outside, under the stone wall. A ceremonial object called a kalash sits atop the building, made of a metal alloy called ashtadhatu (a mixture of eight metals - gold, silver, copper, zinc, lead, iron, mercury and aluminum), which for Hindus defines the sacredness of a building. Here, the kalash also crowns the opening at the top, through which the natural/zenithal light enters, as little as it should into a mysterious place where no more than ten people can stand, into a mysterious place where no more than ten people can stand. That's all.

Turning the assembly hall towards nature is an interesting gesture. It is said that ontogenesis repeats phylogenesis. Here, the architect reverses the relationship: the assembly hall, with its columns, suggested nature with its trees to him from the outset, in the way, says Baltrusaitis, the forest suggested Gothic tree-life to the masons of future European cathedrals; in the way the church porch symbolically narrows, essentializes and elevates the temple courtyard in Jerusalem. Devolution.

For anyone who wants to know more, I refer you to The Architectural Review , September 2010, pp 76-79, where there are all the photos you need to contemplate a mignon, well executed, extremely simple project. The firm is called Sameep Padora &Associates(http://www.sp-arc.net ), and the small temple in Wadeshwar is a highlight on their website.

If you've finished your little Indian story, we can return to Kara Iflak. One of the stalwarts of Moldavian-Vlavic simplicity is the cuteness of Orthodox cult architecture. In all seriousness, a number of scholars, many under metaphysical pressure from a Blaga or a Noica, have decided that the smallness and obscurity of autochthonous masonry are, in combination, metaphysical virtues, necessary consequences of the Moldavian-Vlavic sense of being, or at least the sign of an almost hermit-like experience of the sacred. Given a choice (as a Renaissance prince and ruler of Pocutia), Stephen the Great decided to build many small churches instead of a few king-size cathedrals in Suceava, Rădăuți or on the Nistru, on the borders between Christianity and paganism. Given that the presence of Gothic (in the midst of the Western Renaissance) anchorings, probably arriving from (to) the kingdom of Lesch, proves that, stylistically speaking, the gentleman was not an autarchist in terms of architectural taste (although he was late, Gothic having, until him, used up all its fuel), it follows that, technically speaking at least, there should be no reasons for the modest dimensions, nor for the primitivism of the construction, other than their deliberate assumption in the name of higher causes.

What might these be? Here they are, in a brief enumeration:

1) The assumption of ethnic difference on the territory of the same faith: if the Lezites make ample cathedrals, the mistria, in the manner of Nehemiah's people on the ruins of Jerusalem (the complex of the absence of cathedrals because we fought the Turks, keeping them within the borders of Europe, which thus had time to make its own).

2) My task as a ruler is to bring to the realm of visibility the calophilia in curved forms and, in their shelter, the penumbra, which are the mark of the way I am appropriating the data of my being. The different experience of the "existential space", as Christian Norberg Schulz called it, means that the forms spring nolens-volens in the given dimensions and mutual proportions. From where - from my so-called stylistic matrix, from the Sophianic space. This 'incontinence' is irrepressible, unconscious and independent of any other auctorial intentions I or my craftsmen may have (whom, for breaking the rule, I also repress, like Manole of Arges). It's the Blagian complex of the hill followed by the valley, of the space turned in on itself, of the God present among us in (for??) sacred space.

Now, sustainable development is probably the term we should use to explain the phenomenon of "dwarfism" in medieval religious architecture. The dimensions of Moldovan-Vlavic churches are not small, but adequate, optimal. As we know, there is no money around here. When there is, the predatory elites steal it from us, whatever they called themselves then (and whatever they still call themselves now, for that matter). Although the concept of sustainable development is much later than the Middle Ages, it is probably only in these terms that we can talk about the distribution of resources limited to the vast number of battle sites and fairs that all want a place of worship. Therefore, I use local or nearby materials, the labor force around the site (under the guidance of a given number of probably foreign craftsmen, when they are not in rezbel even with their seniors, in which case I have to rely on local expertise, such as there is); I limit the gauge and technological athleticism to a minimum, in order to optimize the costs of the operation. Let's not forget the long construction time of medieval cathedrals, rarely accessible to the locals (who were left with the space between two battles) and the impressive number of foundations of the Stephen the Great-Petru Rareș era, for example.

Never has the simplicity of Romanian vernacular architecture been seen as a lack of craftsmanship, an inability to decorate. Never has the use of perishable materials been regarded as anything other than a quality, not as an inability to build perennially, in durable materials that stand the test of time. The precariousness, provisionality and paucity of architectural and ornamental solutions have been regarded exclusively as qualities and elevated to the status of metaphysical attributes of the 'people' itself, to the status of a collective ento-ontology. Yet simplicity is an attribute to be inspected when it is deliberately assumed, as in the case of minimalism. However, when we discuss an architecture that is often strictly utilitarian, realized with such modest means, materials and techniques, to celebrate as deliberate a constitutive feature of its constitutive, neither positive nor negative - simplicity - becomes laughable. Moreover, simplicity becomes obvious when it is contrasted with some kind of opulence in relation to which it appears to be an ethical virtue in the aesthetic realm.

We owe the low technological complexity to the darkness of local pre- and post-Byzantine Orthodox architecture, and not (only) to some metaphysics of mediating penumbra in the Christic sense, which would unite the porch to the nave at altitude, but forgets the pig's blister in the window of the clay-tile bordure covered with cochineal hoods, compared to which, in any case, autochthonous churches are from another realm.

As soon as a modicum of prosperity - real or imagined - allowed it, worship architecture, like civil architecture, flourished, the interior spaces brightened. The gold of painting has however softened the interior light of chandeliers and candles. For those who believe in the immanent dwarfism of Byzantine architecture, Hagia Sophia is not only an "original" example, but also an enlightening one. And for the worshippers of penumbra, the same space, bathed in light that seems to "decapitate" and support in glory the dome (as transfigured as Procopius of Caesarea describes it), is proof that there is no alternative to the metaphysics of divine light, and that North Danubian Orthodoxy will not have made itself the exception...

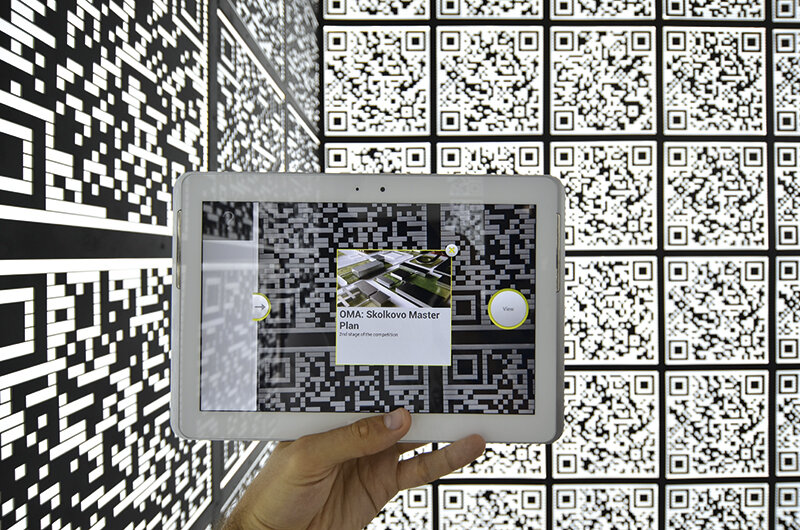

Minor?

There is another way of approaching the problem, that of the minorization of an architecture. This minor character can describe the architecture of a minority, as in the excellent volume Toward a minor architecture (Jill Sunder, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2012), or it can describe an architecture after its powers, made with materials at hand, rediscovering local traditions, tectonics (in its hypostasis of vestigial core, as Frapton calls it, of architecture) and neighborhood, as in Poverism (Augustin Ioan, București:Paideia, 2007, electronic edition on www.liternet.ro from 2005). In other words, it is not an attribute of scale, like Bigness. Minority is a qualitative attribute, it describes an architecture that deliberately abstracts to real resources, real duration, real capacity to build and preserve - of an individual client or a community.