Stairs beyond our intuition

Scales Beyond Our Intuition

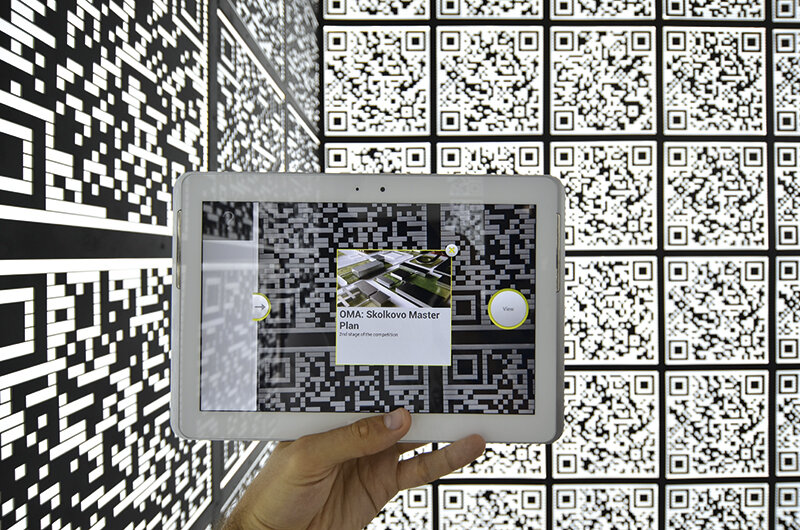

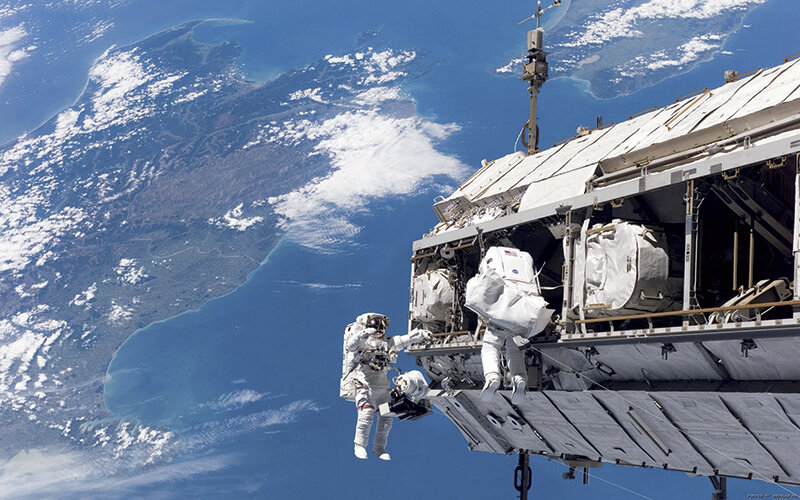

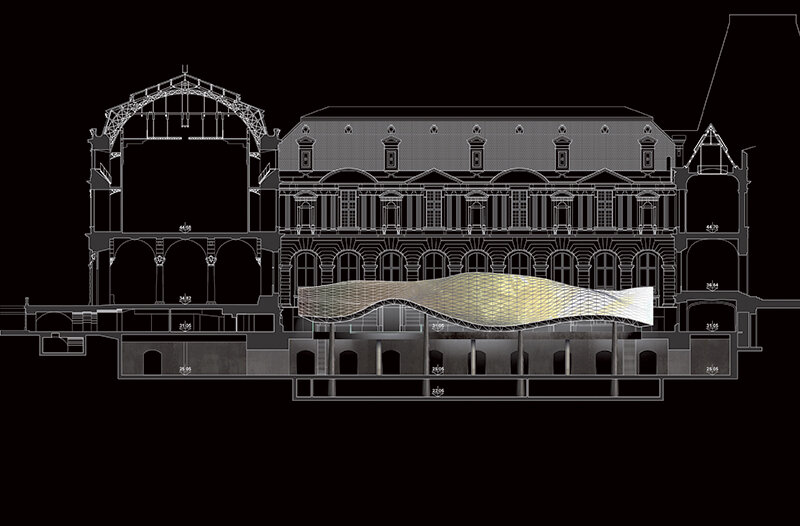

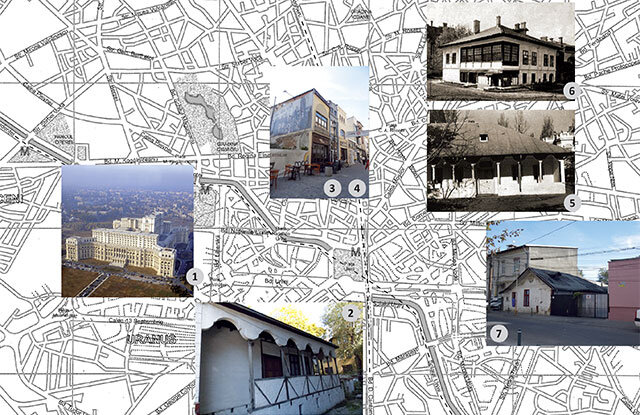

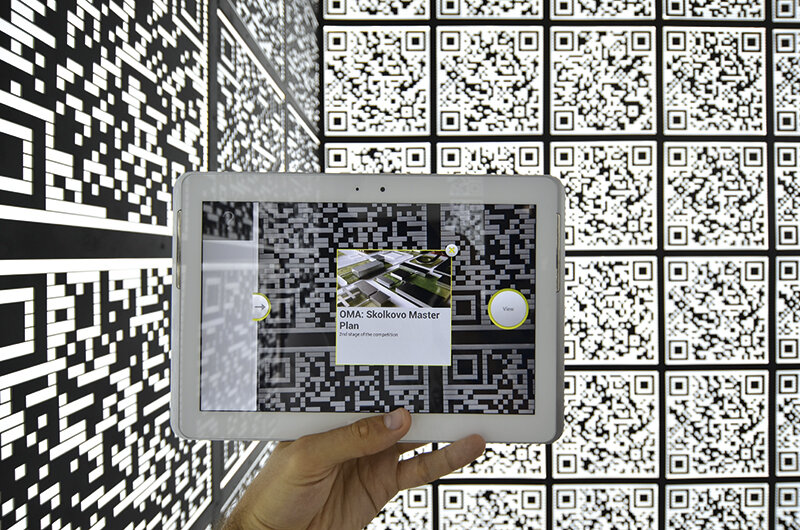

| The scale and complexity of the buildings we design and construct has never been greater than today. A building can be the size of a neighborhood, a city can be assembled almost overnight. A single team can account for the multitude of decisions required. Because the scales involved are unprecedented, and the technologies are too new in contexts that are sometimes unfamiliar, there may be no solid precedents on which to base design decisions. Dealing with this complexity can be a huge challenge for architects. Our computational tools, from CADCAM to building information modeling, offer new ways of tackling this complexity. One of these is the method encouraged by "parametric" thinking, because it tantalizingly generates a lot of complexity, or at least a lot of variation, from a small number of initial settings. But even if a parametric city still looks like a city, that doesn't mean it behaves like a city. The danger of such an approach is precisely the ease with which such complexity is generated from the bottom up, because the more we stretch our designs beyond our intuition, the harder it is to judge them. But there is another side to using computation that could be very useful. Artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies, such as the clever use of simpler algorithms, can be helpful when we extend our own intuition. Or they can give the computer a kind of intuition of its own. In either case, these technologies extend our abilities to deal with true complexity. This is one of the main aspects of the thinking that characterizes much of our current research in architectural design and adaptive computing, as well as the related Bartlett's currents, as I will exemplify below with a few projects that represent the two ends of the design ladder: the very small things and the very big things. |

| Read the full text in issue 5/2012 of Arhitectura. |

| The size and complexity of the projects we are able to design and build has never been so high. Buildings might be the size of neighborhoods, entire cities are assembled almost overnight, and a single team might be responsible for the multitude of decisions required. Because the scales involved are unprecedented, the technologies are often new and contexts can be unfamiliar, there may be no decent precedents on which to base our design decisions, and dealing with this complexity can present the greatest of challenges to architects. Our computational tools from CADCAM to Building Information Modeling provide new ways to deal with this complexity. The sort of method encouraged by "Parametric" thinking is one way, as it seductively generates a great deal of complexity, or at least a great deal of variation, from a few initial settings. But just because a parametric city looks like a city, it doesn't means it behaves like one. In fact it is this ease of generating such complexity from the bottom up that is a potential danger of such an approach, as the further we stretch our designs beyond our intuition, the more difficult it becomes to judge them. There is another side to the use of computation that is potentially useful, however. The technologies of artificial intelligence and machine learning, as well as the informed use of simpler algorithms, can be aids to extend our own intuition, or give the computer a kind of intuition of its own. In either case, they extend our abilities to deal with true complexity. This is one of the core strands of thinking running through much of our current research in Adaptive Architecture and Computation and related streams at the Bartlett, as a few projects at the very smallest and the very largest ends of the design scale may help to illustrate. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |