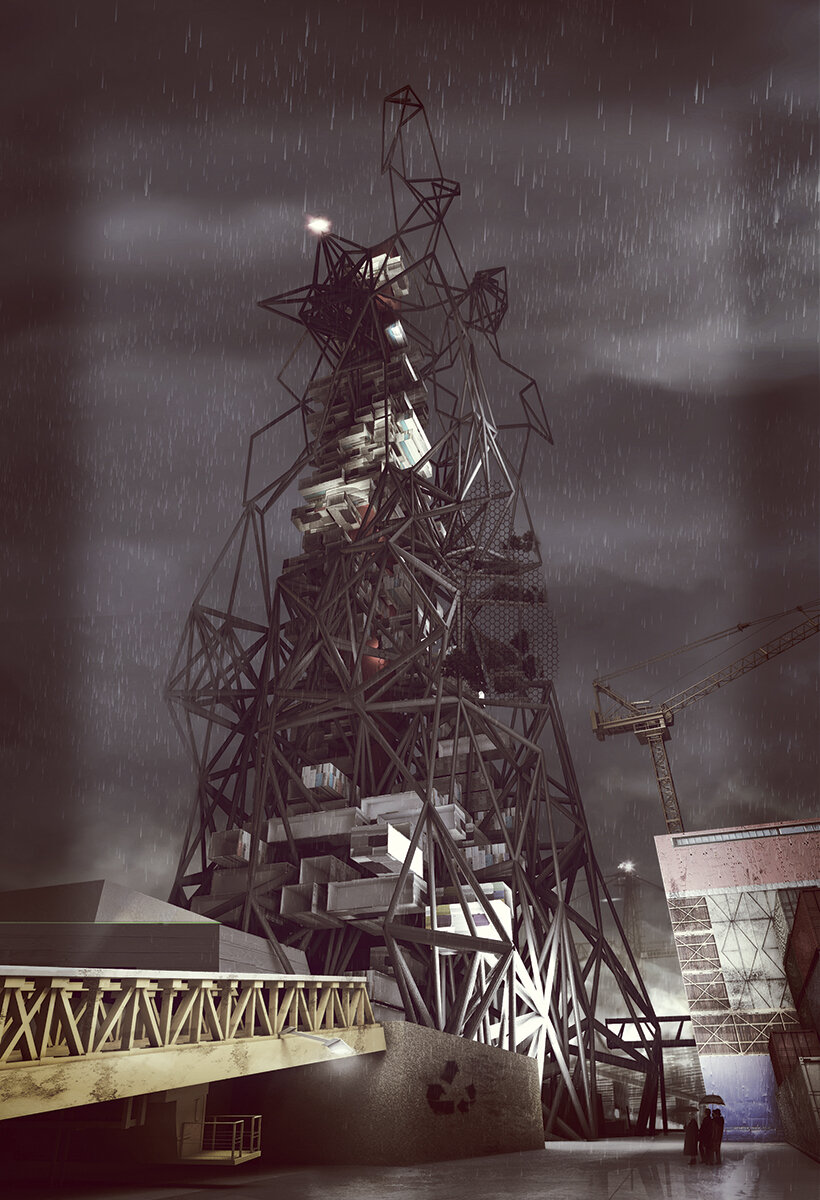

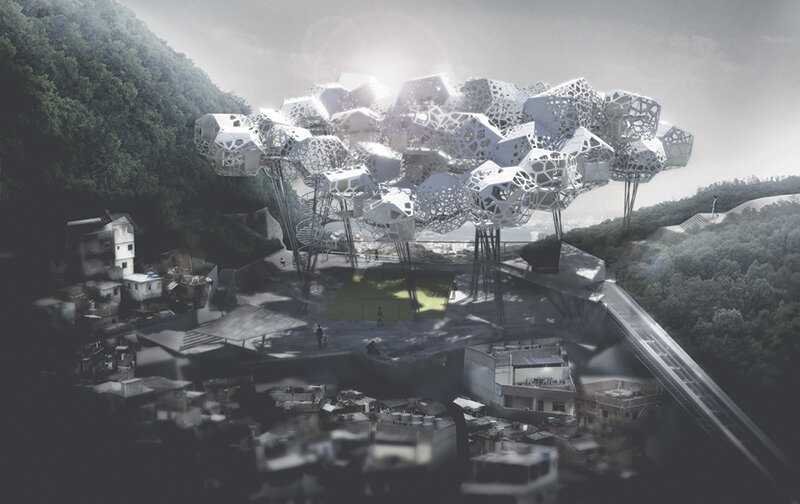

Future adaptable high-density architectures

Future Adaptive Architectures of High Density

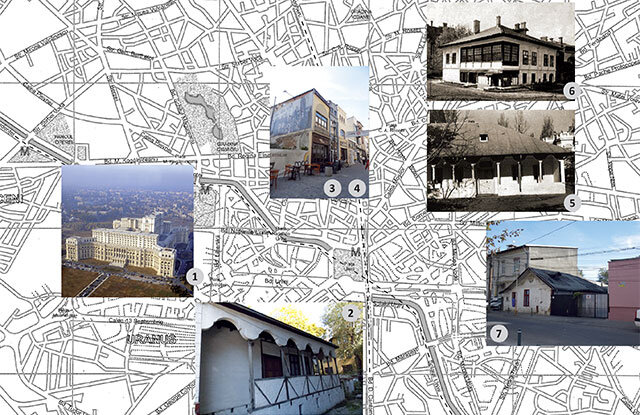

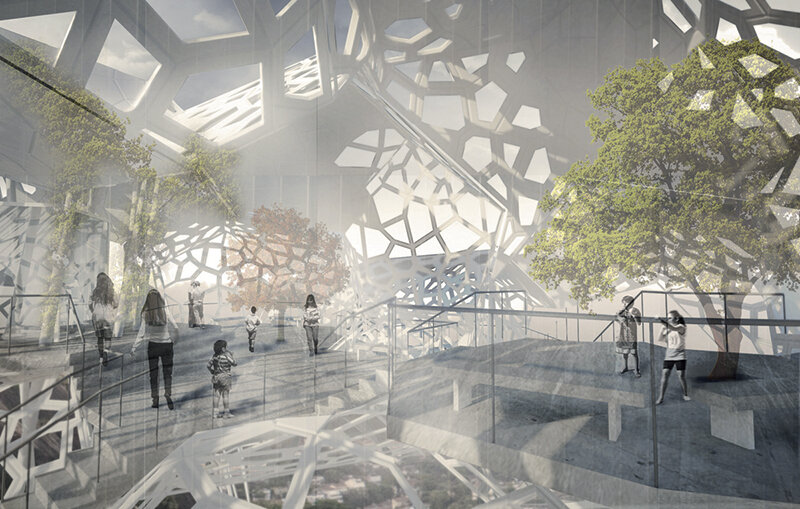

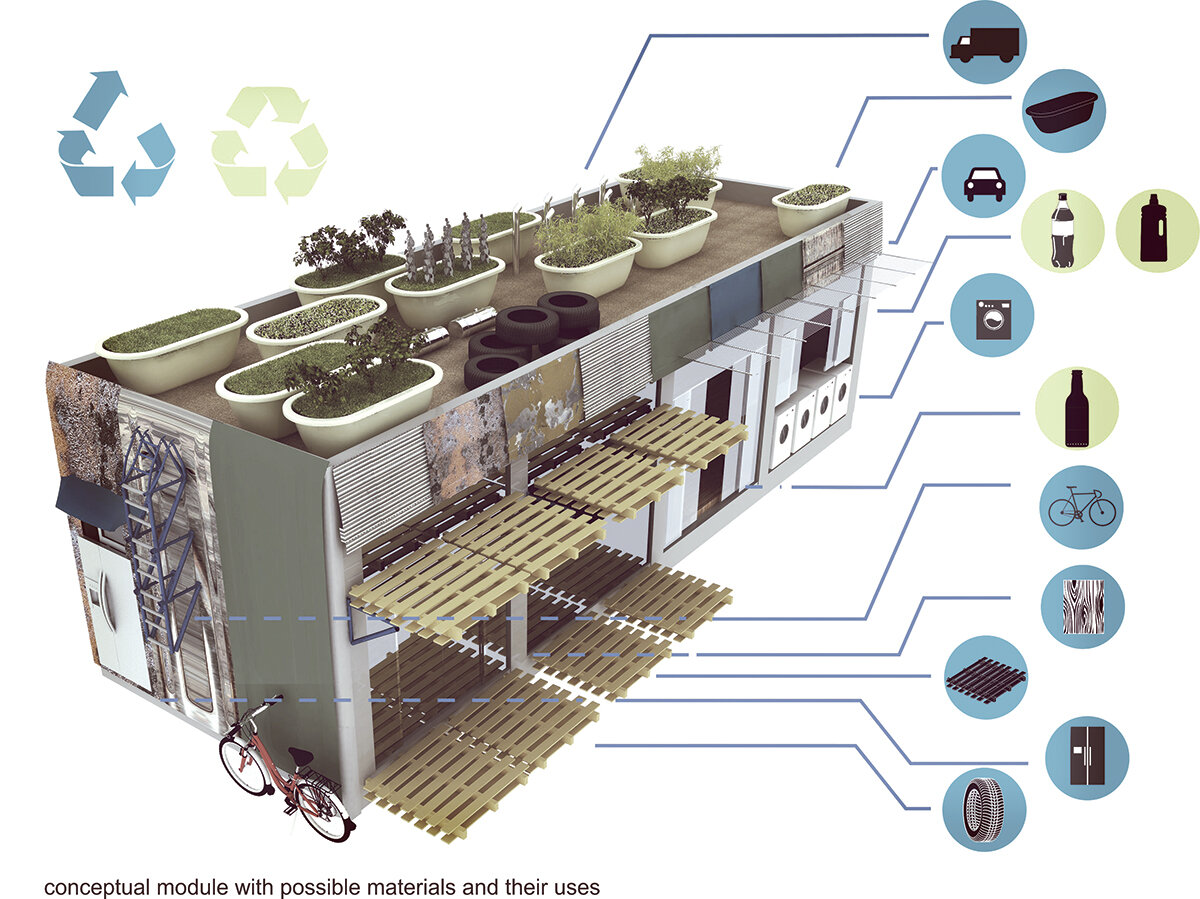

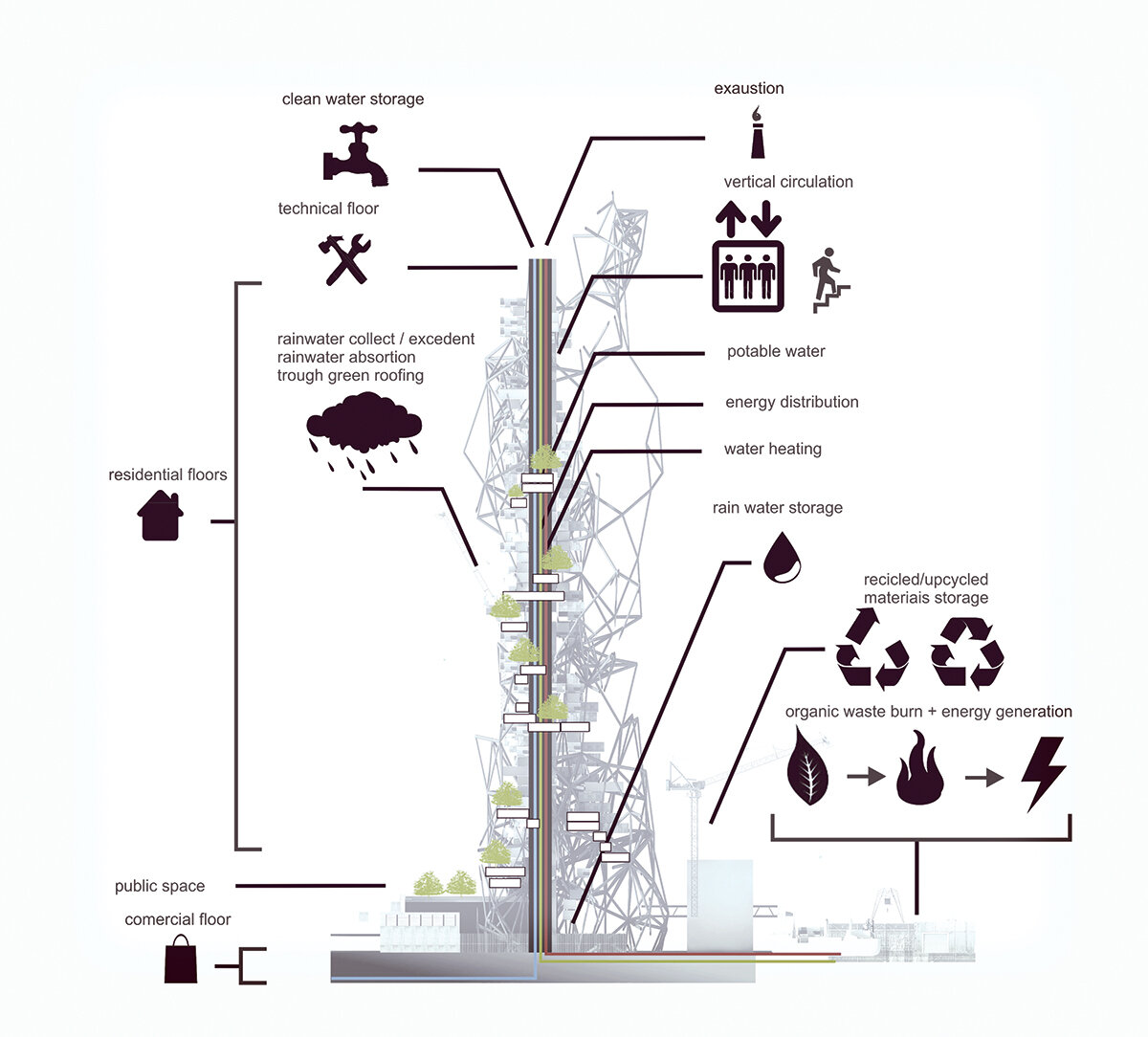

| Currently, population growth is one of the global problems whose severity is potentiated in relation to diminishing resources. In view of this continuous growth, the generation of built environments capable of accommodating the entire population and properly adapted to the context is a major challenge of contemporary architecture. Correctly relating to a dynamic context - in which social, political, economic and environmental conditions are constantly changing - is an even greater challenge. High-density construction, both in terms of built mass and population, is one solution for an increasingly crowdedfuture. However, density as a single criterion for generating built environments and urban quality has limitations. General attitudes towards high-density architectures so far are dual. The positive arguments relate to the rational use of urban land resources in relation to maintaining compact urban development and infrastructure with minimal impact on the surrounding countryside and natural areas, with public transport systems and fuel resources used efficiently. Also, spaces containing large population masses themselves become sources of variation and intensity, offering a rich exchange of ideas, as Patrick Schumacher1 notes. On the other hand, negative implications arise in relation to the same urban components and are identified through the congestion of urban landscapes, the reduction of urban green areas and the emergence of heat islands, the deterioration of urban network and traffic infrastructure through overloading and, last but not least, the increase in psychological stress of inhabitants. Architecture cyclically rewrites its formal and morphological language, generally as a counter-reaction to previous negative experiences and in relation to changing contexts. Over the last 30 years, large-scale development has been accompanied by the homogenization of the built product, leading to the maximization of the economic value of the project at the expense of social value.2 We are currently witnessing a new transition in the way architecture is being written, where the expansion of the built environment based exclusively on profit-making and speculative investment is being abandoned through the manifestation of recent economic crises. At the same time, a more subtle transition is taking place in urban societies, due to the migration of jobs in the wake of the same crises and recent changes in family structure. Today, the monogamous mononuclear family, as it existed in the last century, is no longer exclusively the norm. Its static structure based on hierarchies and tree-like relationships is being diluted by the emergence of dynamic, elastic structures capable of abrupt transformations, based on relationships of association and consociation built on principles other than those based exclusively on blood ties. In relation to this context, there is a need for new rules of composition of constructed environments. Architectural experience to date has shown that large-scale urban projects are generally incapable of long-term adaptation, generating urban and social conflicts and ultimately leading to their abandonment. A design that vertically multiplies the same plan layout or over-determines buildings in the search for the perfect match between form and function is no longer a viable response to today's changing world. Such urban developments are rigid, inflexible, incapable of growth or dynamic adaptation to change, and are characterized by a decrease in social complexity due to the reduced mix of activities. Their impact on the immediate environment due to their inability to adapt is also high and they constitute a continuous source of stress on the urban fabric. The time of simplified built environments, generated by programmatic directions responding to a finite set of requirements, identified by schematizing the contextual elements of a given time sequence, has passed. The main theme of contemporary design is to relate to a constantly changing context. The process of urban development itself is a complex, evolving one, and the nature of contemporary urban life is very different from the traditional city, being much more complex, heterogeneous, interrelated and dynamic3. For the contemporary city, made up of a dense and varied superposition of states, information, populations, activities and relationships, a complex design strategy is needed that is able to incorporate all these components. |

| Read the full text in Arhitectura 5/2012. |

| 1. Patrick Schumacher, My kind of town, http://www.architecturetoday.co.uk/?p=22997, accessed on 10.09.20122. Nic Clear, A Near Future, in: Castle, H., Clear, N. (eds.), "The Near Futures", Architectural Design Vol.Chye Kiang Heng, Lai Choo Malone-Lee , Density and Urban Sustainability: An Exploration of Critical Issues, in: Designing High-Density Cities for Social and Environmental Sustainability, Edward Ng (ed.), Earthscan, London, 2010, p. 41-52 |

| From the perspective of the continuous growth of population, generating built environments capable of housing the entire population and adapted properly to the context is a major challenge of contemporary architecture. Proper relationship to a dynamic context in which the social, political, environmental and economic components are constantly changing is even a greater challenge. High density buildings, both as constructed density or as population density, represent a solution for an increasingly crowded future.

General attitudes towards high density architectures so far are dual. The positive arguments take into account the rational use of urban land resources, in relation to maintaining a compact urban and infrastructure development, with minimal impact upon the surrounding rural and natural areas, with efficient use of urban transportation systems and fuel resources. Also, areas including major population become themselves sources of variation and intensity, providing a very rich exchange of ideas, as Patrick Schumacher1notices . On the other hand, negative implications arise in relation to the same urban components and are identified by the congestion of urban landscapes, reduction of urban green areas and the occurrence of heat islands, deterioration of urban networks and traffic infrastructure by overloading, and not least an increase of psychological stress for the inhabitants. Architecture is cyclically rewriting its formal and morphological language, generally as a counteraction to previous negative experiences in relation to context changes. In the past 30 years, constructions of large scale developments were accompanied by homogenization of the built product, resulting in maximizing the economic value of the project at the expense of social value2. Urban societies undergo a subtle transition in parallel, due to jobs migration from the perspective of the same crises and recent changes in family structure. Today the mononuclear monogamous monogamous family as it existed in the last century is no longer exclusively the norm. Its static structure based on hierarchy and tree-like relationships is diluted by the emergence of dynamic structures, elastic and capable of abrupt changes, based on association and cohabitation relationships built on other principles than those solely based on blood ties. In relation to this background, new rules are needed for composing the built environment. Architectural experience so far has shown that large-scale urban projects are generally incapable of long-term adaptation, gene-rating urban and social conflicts and eventually being blamed in the end by being left empty. A design that vertically multiplies the same plan scheme or over determines constructions while looking for the perfect match of form and function is no longer viable in light of current changes. Such urban developments are rigid, inflexible and incapable of growth or dynamic adaptation to changes and are characterized by a decrease of social complexity due to a low mixing of activities. Also, their environmental impact on the immediate surrounding due to inability to adapt is great, as they are a continuous source of stress for the urban tissue. The moment of simplified built environments, generated by programmatic directions that meet a finite set of requirements, identified by the schematization of contextual elements in a specific time sequence has set. The main theme of contemporary design is relating to a constantly changing context. The process of urban development itself is a complex process constantly evolving, and the nature of contemporary urban life is very different from that of the traditional town, being more complex, heterogeneous, interrelated and dynamic3. For the contemporary city, consisting of a dense and varied overlapping of layers, information, populations, activities and relationships, a complex design strategy is required, one that's able to incorporate all these components. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |

| 1. Patrick Schumacher, My kind of town, http://www.architecturetoday.co.uk/?p=22997, accessed in 10.09.20122. Nic Clear, A Near Future, in: Castle, H., Clear, N. (eds.), "The Near Futures", Architectural Design Vol. 79, No. 5, September/October, Wiley, London, 2009, p. 6-113. Chye Kiang Heng, Lai Choo Malone-Lee, Density and Urban Sustainability: An Exploration of Critical Issues, in: Designing High-Density Cities for Social and Environmental Sustainability, Edward Ng (ed.), Earthscan, London, 2010, p. 41-52 |