The fascination of invisible technology

The fascination of invisible technology

| For a while I couldn't decide whether microarchitecture is a beautiful or a horror dream. If it's a reverie about a superarchitecture, but a good and gentle one with all people and in harmony with the environment or if it's a nightmare about life in a recycled trailer on an overpopulated planet. I don't know whether to take it as a new Western extravaganza, a new challenge for creative architects who can afford to experiment, or whether it is preparation for a new way of thinking about existence, of "saving the future", suggested by hints from above. It's probably all of the above. The good thing is that, until we define it more precisely, it still allows everyone to relate to what suits them and ignore the rest. |

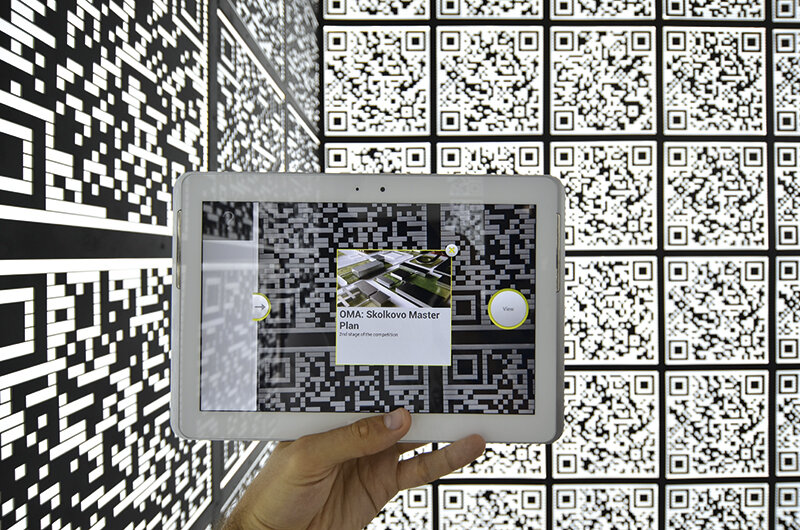

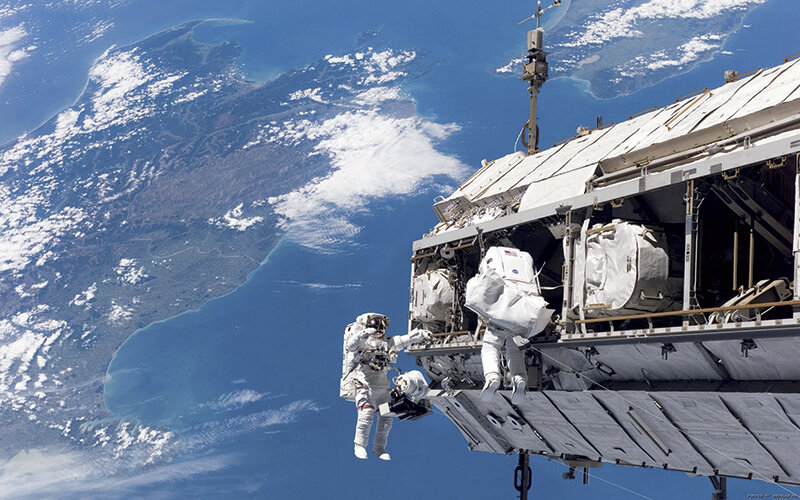

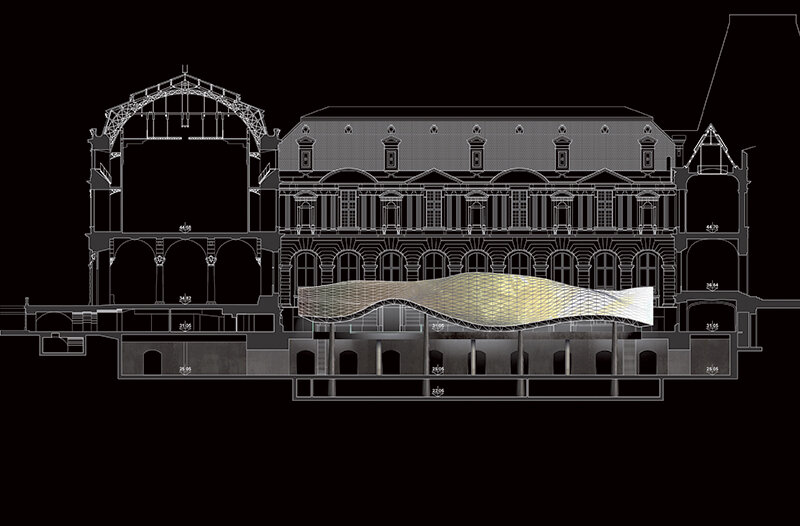

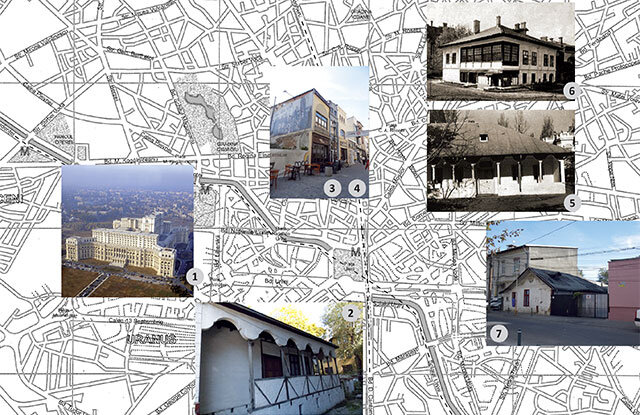

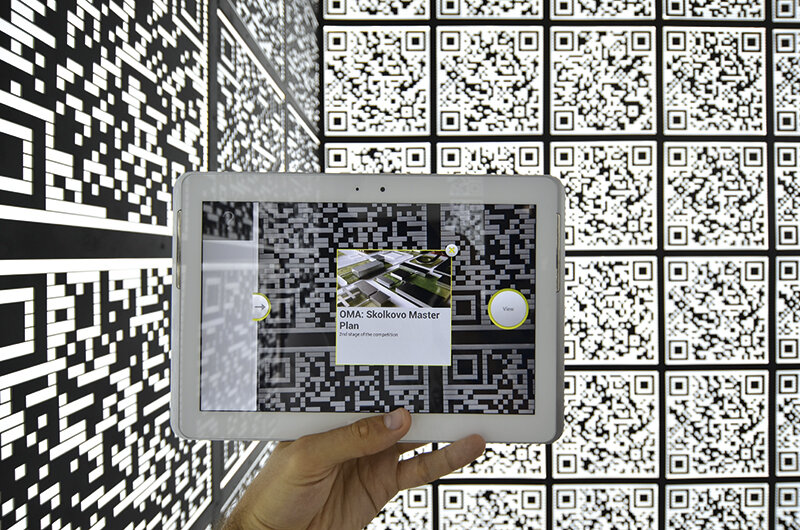

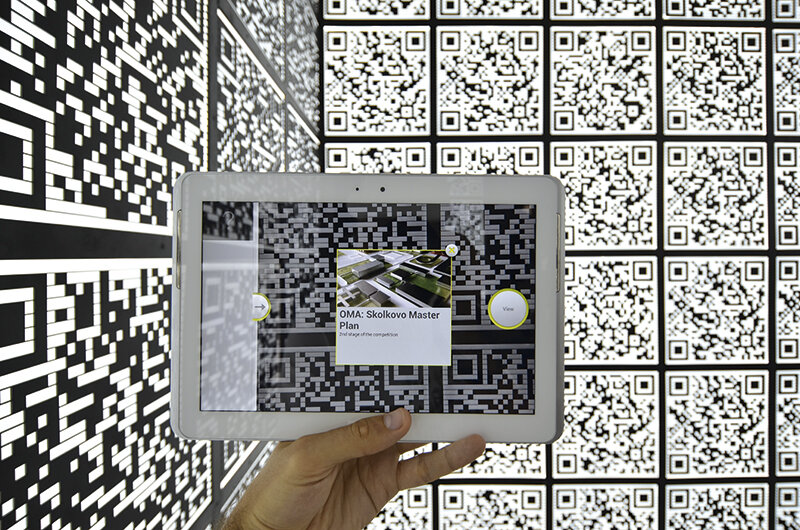

| We learn optimistic dramaturgs about evolving microarchitecture in today's avant-garde world. Architects have greeted the novelty with enthusiasm, those who can have rushed to get involved, and interesting things have already been produced. Like, from the few I know of: The Erich Kästner Museum in Dresden, a museum the size of Erich Kästner's world on 30 square meters on the ground floor of Uncle Augustin's villa, an interactive micro-museum that through media technology gains space and globality; the Russian pavilion at the Venice Biennale, where exhibits are visualized by accessing the bar codes on display; the flagshipstore in Zurich, which sells bags made from tarpaulin sheets in seventeen stacked containers salvaged from the shipping trade. Not to mention all the naughtiness to be found in the 12/2004 issue of Detail magazine. The criteria of my mini-lecture include the keywords of microarchitecture - economy, recycling, mobility, flexibility, temporariness, design, ecology, autonomy, but also con-textuality, of course coupled with high and innovative technology. But an unostentative technology, modestly subordinated to architectural performance. But alas, from here, in Romania, we can only watch from afar the evolution of this new program (should I call it a program?), either with admiration or envy, depending on the character. Some of us may even be circumspect and grumpy, as if faced with a fad that they can no longer monkey with. For neither conditions nor aptitude have ever made technology the strong point of our architecture, any more than responsibility towards nature or the spirit of rational economy. Moreover, some have remained allergic to directions from above, from times when all were inimical to us. The attitude to microarchitecture depends on which of its many facets we refer to. A cockpit, a mobile research station in you-know-where, in difficult or impossible places, a submersible or a space capsule have an architectural component so specialized and technically subordinate that most of us watch them like the Discovery Channel. A little closer, more sympathetic and exciting are objects such as nomadic dwellings, vacation homes, exhibition micro-galleries, shelters, info points, urban stations, workshops, etc. - single-celled, temporary, one-legged, one-legged, crouched, suspended, suspended, folding, walked or grown out of the ground or walls. But if you're curious to find out who would want to live or go to work in a salvaged container - and willingly - you'll find it hard to find users. Finally, I dare to leave the zone of the high-performance present and futuristic visionaryism characteristic of microarchitecture to look back at some of its possible origins. This brings me to archetypes such as the tree houses with stoves and doormats of some tribe in New Guinea, the yurts, igloos, igloos, tholos, lavvu (of the Sami people), cave dwellings, huts, lakeside huts, etc., and also our own kindergartens. Yes, then the audience extends to the peripheries and includes us. The need for economic rationality, spatial optimization, more clever construction details and pragmatic choice of materials have also stimulated popular creativity. |

| Read the full text in issue 5/2012 of Arhitectura magazine. |

| For a while I was undecided as to whether microarchitecture was a beautiful dream or a dreadful vision, whether it was a reverie about a superarchitecture, albeit one that was good and gentle towards all people and in harmony with the environment, or a nightmare about life in a recycled trailer on an overpopulated planet. I don't know whether we should take it as a new western extravagance, a new challenge for creative architects who can afford to experiment, or whether it is the prelude to a new way of thinking about existence, about "saving the future", as the above indications would suggest. It is probably all of these things together. The good part is that until we define it more precisely it will go on allowing each person to relate to whatever suits him or her and to ignore the rest. |

| We discover optimistic scenarios about the evolving microarchitecture in the world of today's avant-garde. Architects have enthusiastically greeted the new. Those who have been able have been quick to get involved and have already produced interesting works. From the few I am familiar with, these include: the Erich Kästner Museum in Dresden, a museum that encapsulates Kästner's world within thirty square meters on the ground floor of Uncle Augustin's villa, an interactive micro-museum that gains space and universality using media technology; the Russian pavilion at the Venice Biennale, where the exhibits can be visualized by accessing their barcodes; the flagship Store in Zurich, which sells bags made from recycled materials in seventeen stacked containers salvaged from maritime shipping; and not to mention all the daring ideas to be found in issue 12/2004 of Detail magazine. The criteria for this mini-selection of mine include the keywords of microarchitecture: economy, recycling, mobility, flexibility, temporariness, design, ecology, autonomy, and, of course, context, in combination with cutting-edge, innovative technology, albeit a technology that is unostentatious and modestly subordinated to architectural performance. But here in Romania, alas, we can only gaze from afar at the evolution of this new program (can I really call it a program?), either admiringly or enviously, depending on our character. Some might even view it in a circumspect or nitpicking way, the same as they might look at a fashion they can't mimic. For, neither circumstances nor inclination have ever made technology a strong point of our architecture. And nor have responsibility towards nature or a spirit of rational economy ever been a strong point. Moreover, some have remained allergic to directives from above since the times when these were inimical to us. Our attitude towards microarchitecture depends upon which of its for the time being multiple facets we are referring to. A cockpit, a mobile research station in the unlikeliest of places, a submersible, and a space capsule have such a specialized and technologically determined architectural component that most of us look at such things as if they were straight from the Discovery Channel. A little more familiar, pleasing and exciting are objects such as nomad holiday homes, microgalleries, shelters, info points, urban stations, workshops, and so on: mono-cellular, temporary, one-legged, suspended, articulated structures, which sprout from the ground or from other walls. But if you are curious to find out who would willingly choose to live in or go to work in a recycled container, you discover that such buildings' users are hard to find. Anyway, let me venture to move away from the zone of the high-performance present and the visionary futurism characteristic of microarchitecture in order to look back at some of its possible origins. Here we discover archetypes such as Papuan tribal tree houses with stoves and doormats, yurts, igloos, tholoi, Sami lavvu, rupestrian and lacustrine dwellings, bothies, and also Romanian bordeie. In this case, the audience expands to the peripheries and encompasses Romania. The need for economic rationality, spatial optimization, skilful structural details, and pragmatic choice of materials also stimulated folk creativity. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |