... in the absence of reality

When the city, the street, the building are in a constant state of dematerialization under the imprint of trends in modern architecture, technology comes with an extension of the way we perceive pure architectural language. The evolution of technology and its compression into casings easily carried in a jacket pocket has radically changed the way we use the internet, how we use a digital camera, and how we interact with public and virtual spaces.

Mobile technology puts, alongside the tee and the echer, a new set of tools in the form of seemingly utopian applications such as Augmented Reality that can be used in architectural experiments, from virtual volumetrics placed in real spaces to sustainable tendencies to reactivate abandoned spaces.

Without getting into discussions about code written in programming languages and 3D modeling, the Augmented Reality application, hereafter called AR (augmented reality), can be presented simply as a sheet of glass through which, if we look at our surroundings, we can interact with drawings seemingly located in the coordinates of the real world and filling an information or volumetric gap.

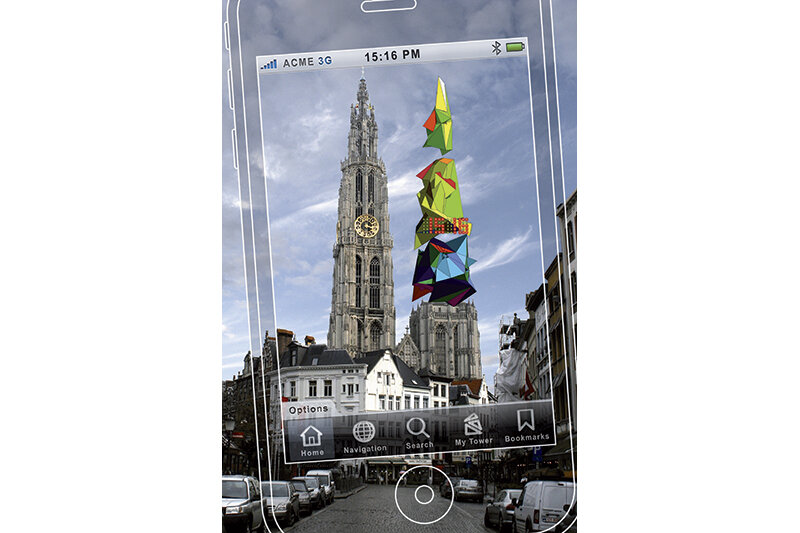

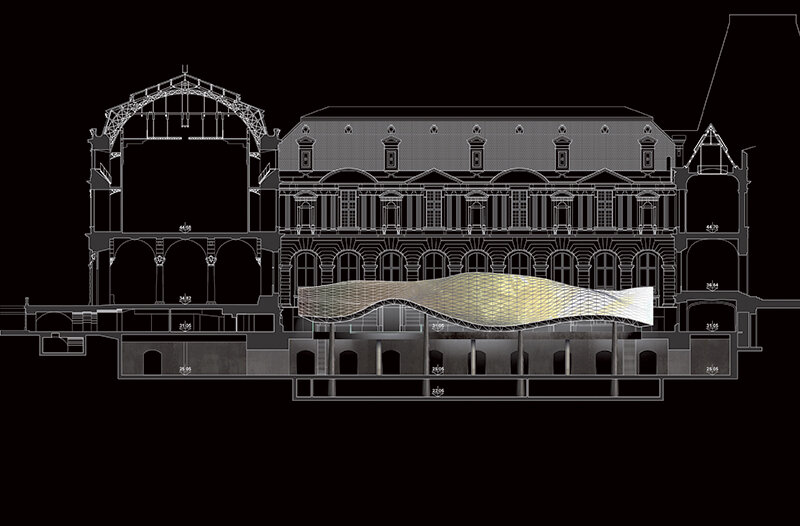

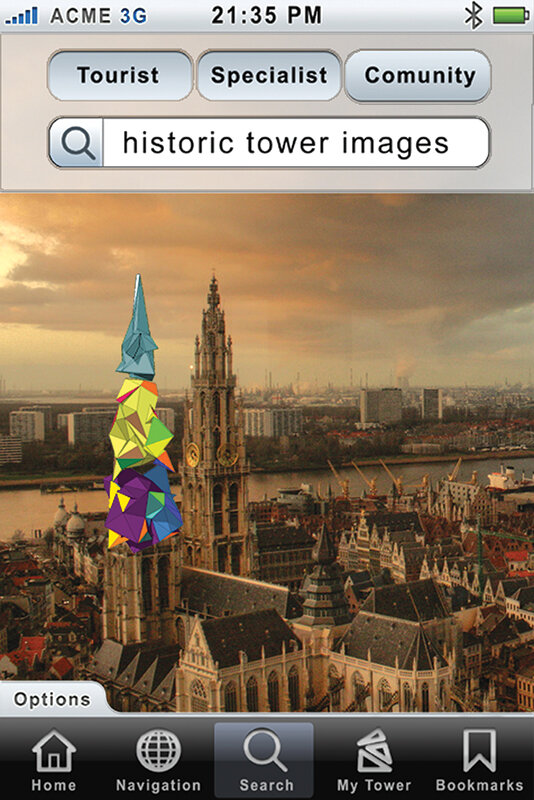

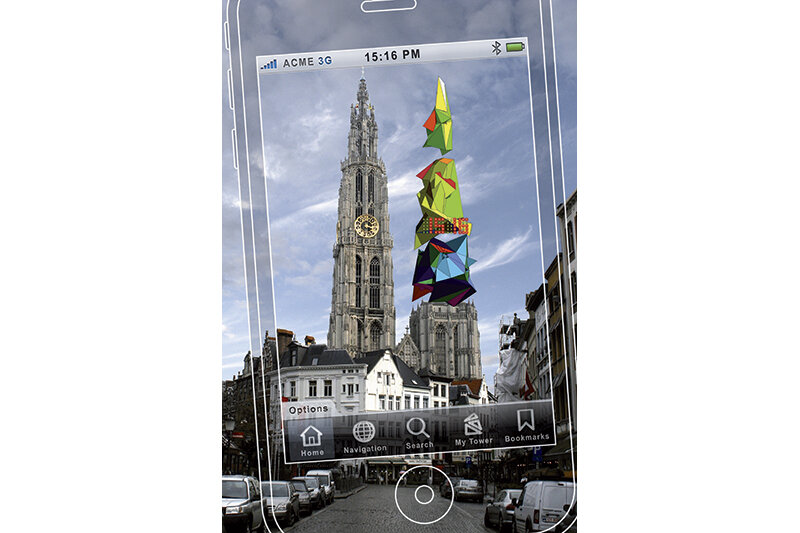

Tower 2.0 emerged as a response to the 'Designing Absence' competition, launched in spring 2010, which set out to imagine the unfinished spire of St. Mary's Cathedral in Antwerp. The competition had been featured by several online architecture sites and proved to be particularly challenging, while also taking an unusual approach: designing the unfinished spire of the cathedral by emphasizing the absence of the cathedral itself. Once upon a time, the organizers achieved their goal by launching the competition in a way that brings to mind the works of Christo and Jean-Claude, Zevs or Alexandre Orion.

The conditions for participation were ideal, with a two-month deadline, no restrictions on the concept, the materials used, the budget or the feasibility of the intervention. All that was wanted was to paste the solution on a simple photo made available on the competition page, so given these premises, the opportunity to play the game proposed by the organizers proved too tempting to miss.

The initial approach was somewhat classical. Historical building materials, construction systems, color and stereotomy, all too dated and inappropriate to the subject. The use of augmented reality was, in my opinion, the only way to meet the conditions imposed by the theme, while at the same time realizing a blend between the history of the place and our society today.

Built in several phases, the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwewekathedraal has had a turbulent history beginning in the 9th century with a small chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary. In the 12th century it was converted into a Romanesque church, and in 1352 it was changed to the Gothic style of the time, making it the largest Gothic church in the Netherlands. Over the centuries, there were enough obstacles to the completion of the southern spire, from fires to rebellions, from wars to economic difficulties1. What is certain is that this episcopal cathedral has, for more than a millennium, been a landmark in the city and the region, in the same way that the cathedrals of Aachen, Milan and Chartres have been: it has focused a community around it, serving as a landmark in the city and its surroundings, literally and figuratively. Whether we are talking about the spiritual guidance carved on its walls or the fact that it was the tallest building for dozens of kilometers, the cathedral was a focal point for everyone around it.

Often in the Middle Ages, it was cathedrals that housed and sheltered schools, many of which would eventually become renowned universities such as those at Chartres, Paris, Laon, Reims or Rouen. They were veritable "fortresses of knowledge", serving both the clergy - as the main repositories of knowledge - and the laity, organized in a community attached to the diocese.

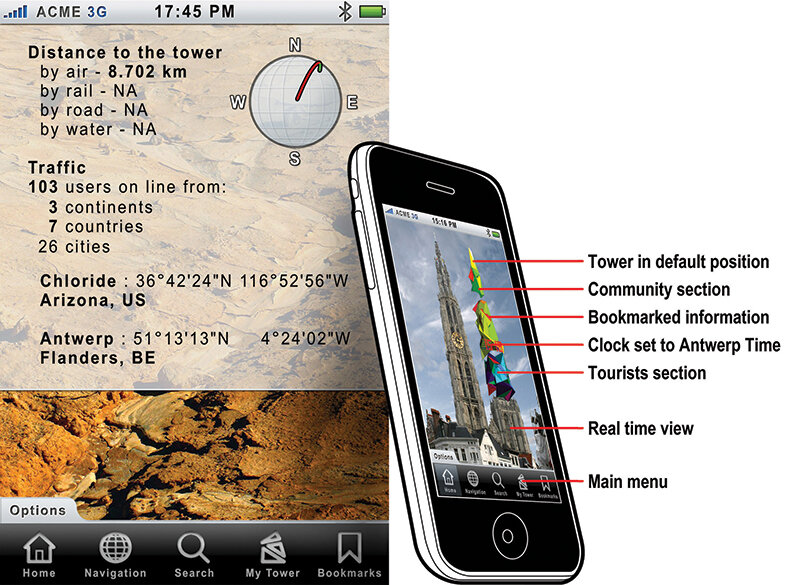

Analyzing the cathedral from the perspective of the competition theme and reviewing the elements that define it, four main components can be crystallized: the physical, the sacral, the social and the educational. Through the proposed solution and the use of augmented reality, I wanted to emulate these defining elements, integrating them in a virtual way into Tower 2.0 - the new spirit of the cathedral. I envisioned the new tower as a smartphone app, a program that connects, like a portal, an online server containing data dedicated to the cathedral and its users. The server would contain a database that feeds this application with information, which crystallizes three-dimensionally, according to its volume, type and category, and the history of interactions with users. The database would be hosted and maintained by the Catholic Diocese of Antwerp, and thanks to a Voronoi-like algorithm2, the volume of information would dynamically build up, subdivide or multiply.

The Tower 2.0 information would be structured on three levels: the first, reserved for the local community, would graphically represent the schedule of services and celebrations, as well as all the details of the religious life of the parishioners. The second would contain information dedicated to specialists studying the cultural heritage of the cathedral, while the third level would be reserved for data relevant to tourists (visiting hours, itineraries, images and text related to the monument). Each facet of the tower would either allow direct access to the desired information, or would launch pages dedicated to it in the application's internal browser.

Kept in place thanks to its own GPS coordinate system, the tower would be in a constant relationship with the supporting building, ensuring a correct and constant positioning in the real space around the cathedral. The database would become active only when the visitor is aligned with the tower, in the sense that both the user (phone or tablet) and the virtual tower should be on the same axis. This condition would allow orientation in the real space of the user, which could be useful in the narrow streets of Antwerp's historic city center. The special charm of this condition would be all the more special since, when accessed from a great distance, from another continent for example, the tower would appear rotated or tilted or even below the user's horizon, thanks to its real position on the Globe. Because of this, a remote user following the application's internal compass "looking for" the tower would have the satisfaction of realizing his or her spatial positioning relative to Antwerp and the cathedral, and would realize what we all know but do not realize so often, that the Earth is, after all, a large sphere.

The cathedral has always been a monument that houses information, guides and unites people. The tower I envisioned would be a virtual representation of information itself, one capable of creating a community on a global scale, giving it parts of and guiding it through the real world of Antwerp Cathedral.

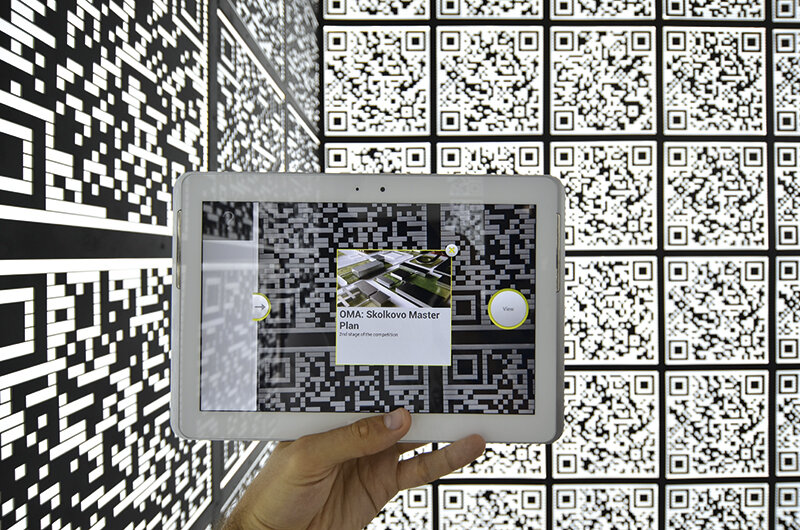

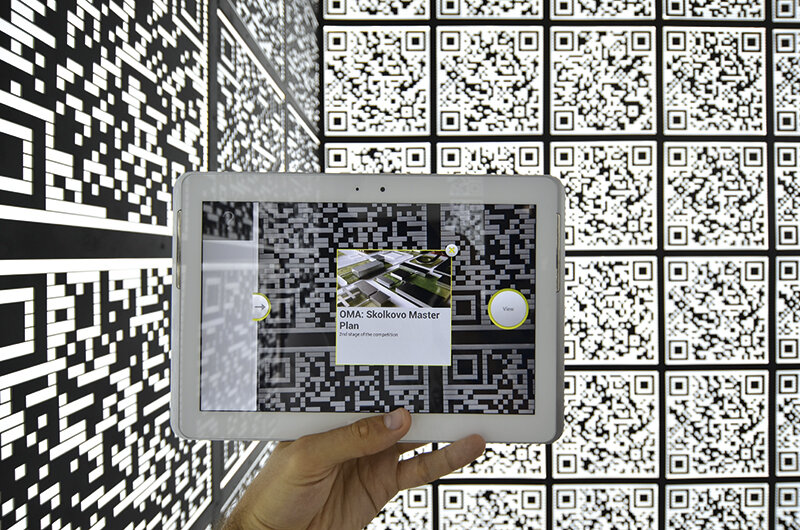

Even today, almost 15 years after the term Augmented Reality was coined, the technology is still full of potential. It makes sense for every architect to envision the opportunity to have their plans coded in a way that launches, once scanned with a smartphone or tablet, a fully textured, dynamic, three-dimensional model, responsive to the sunlight conditions at the moment of visualization, floating over the drawing that is so often misinterpreted by either the beneficiaries or the builders. Technological developments in recent years have, however, made it possible to apply this way of annotating reality much more widely, going far beyond the sphere of architecture. It should be noted that at the time I was imagining my Tower 2.0 app, there was no iPad and smartphones did not allow dynamic real-time displays.

Today, the iPad is already in its third generation, and smartphone processors are comparable in performance to the average computer in 2010. Augmented Reality is opening up more and more opportunities for applications in the reality around us as time goes by. With Google launching the Glass project3, prototypes of contact lenses with integrated displays powered wirelessly by electricity4, mobile phones with increasingly powerful operating systems, code providers creating increasingly user-friendly interfaces5, all of this will inevitably lead to a re-evaluation of the space around us, changing it not only in terms of its physical quality, but also in terms of the information and poetics it will house.

If the solution for the Tower 2.0 competition works with the avant-garde theories about AR since 2010, the next project puts a series of architectural solutions in the context of functional applications.

Since the first releases of AR apps, advertising agencies have monopolized them in campaigns that abruptly pushed the concept of AR into a banality akin to giant facade advertisements.

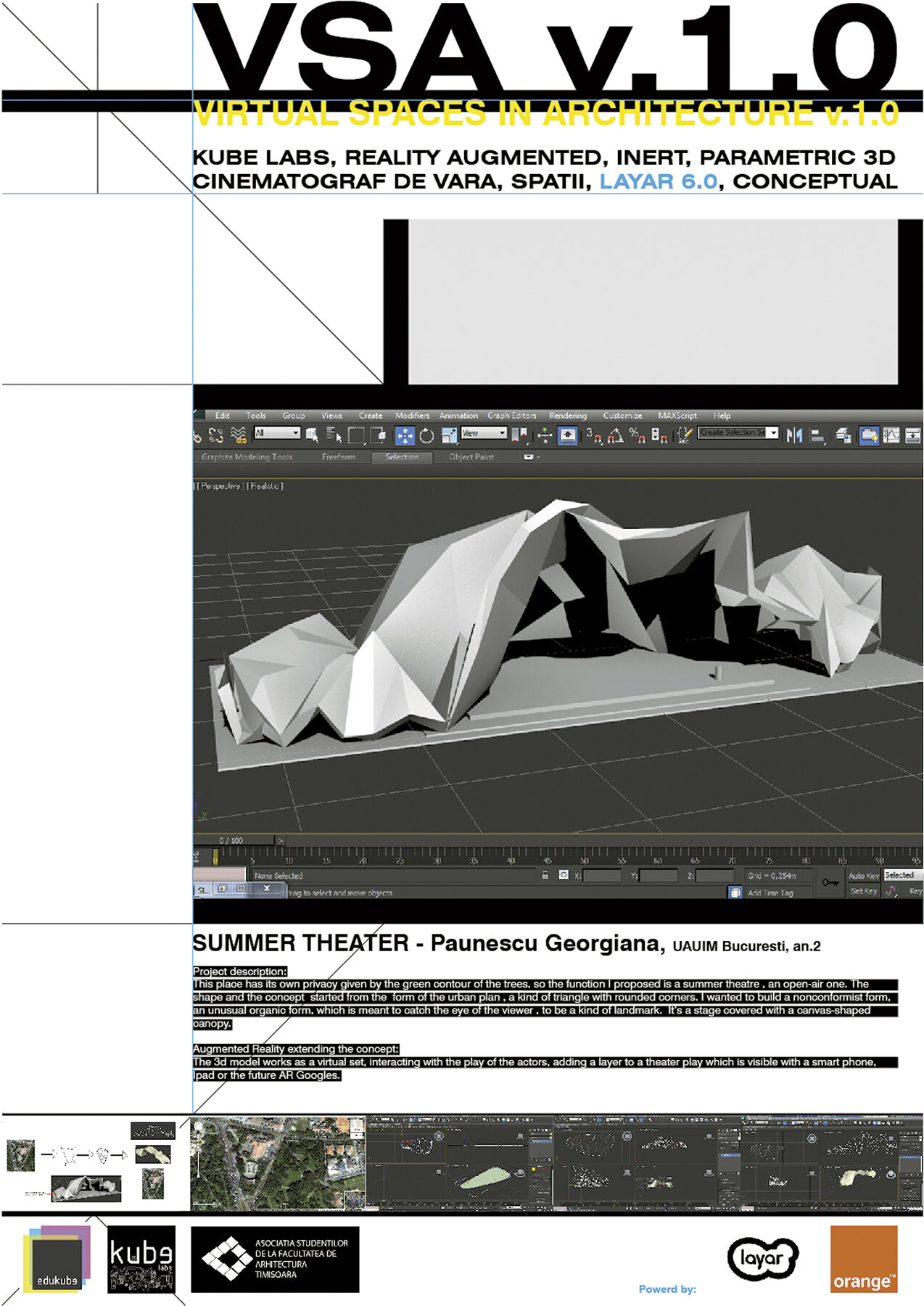

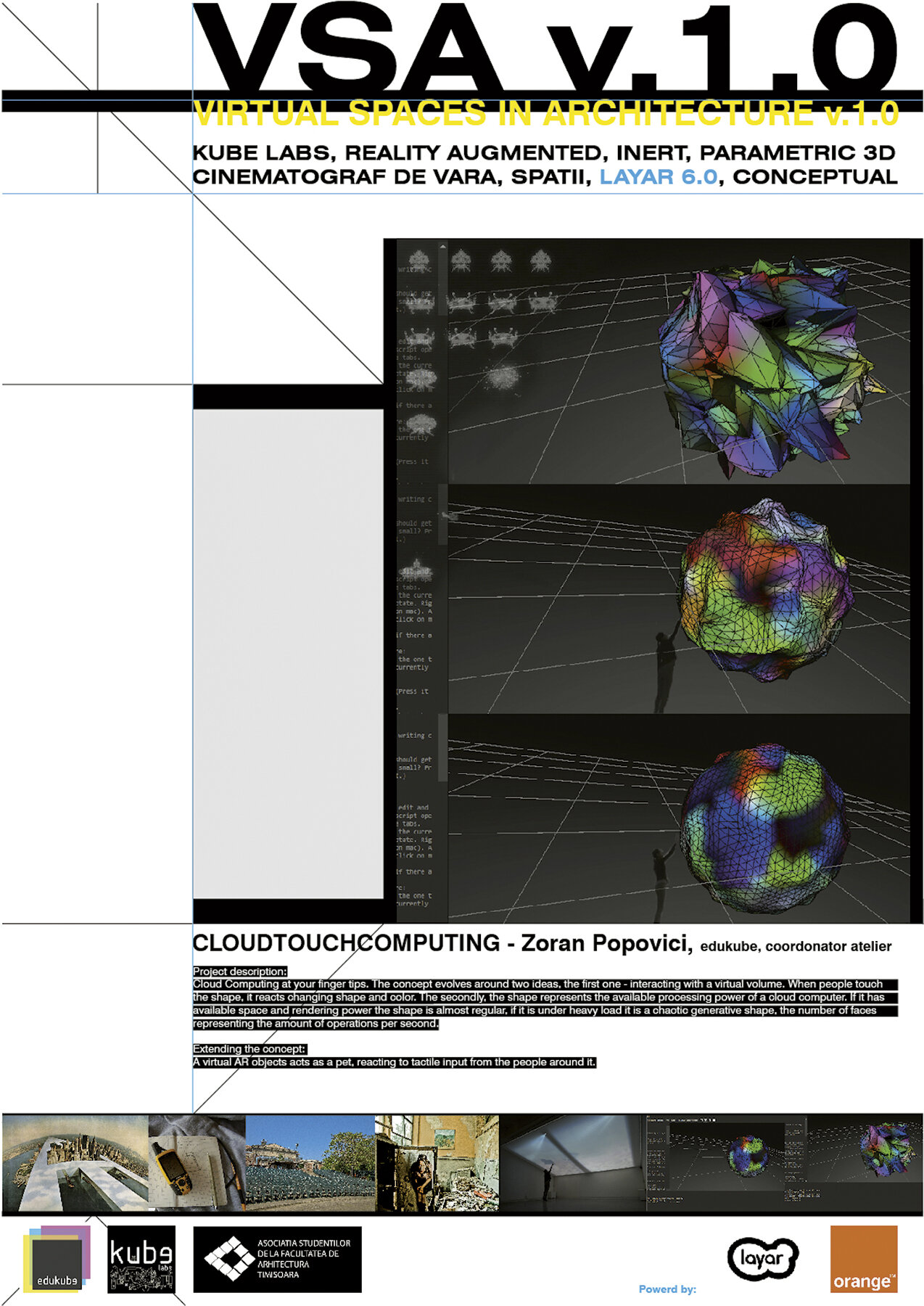

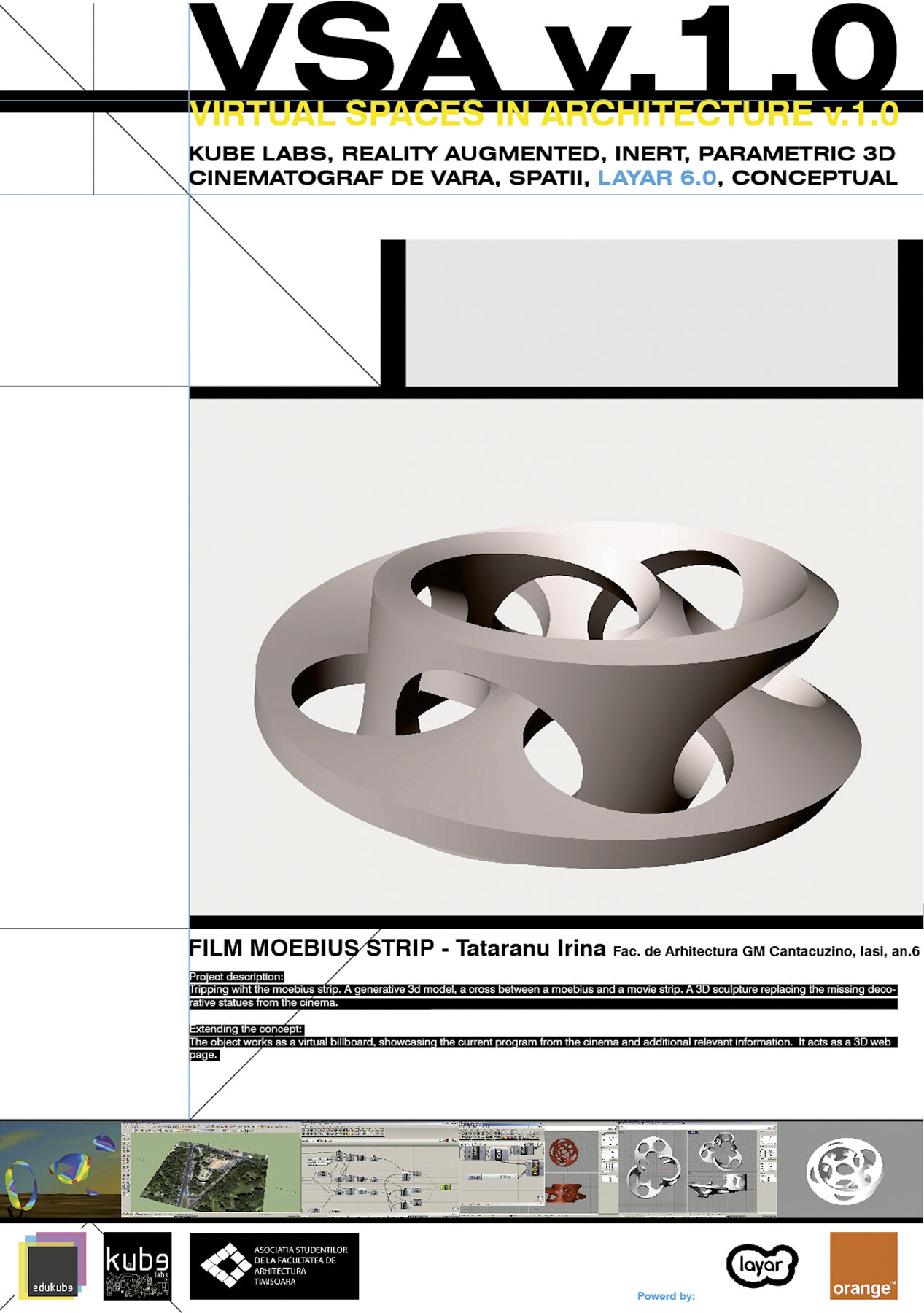

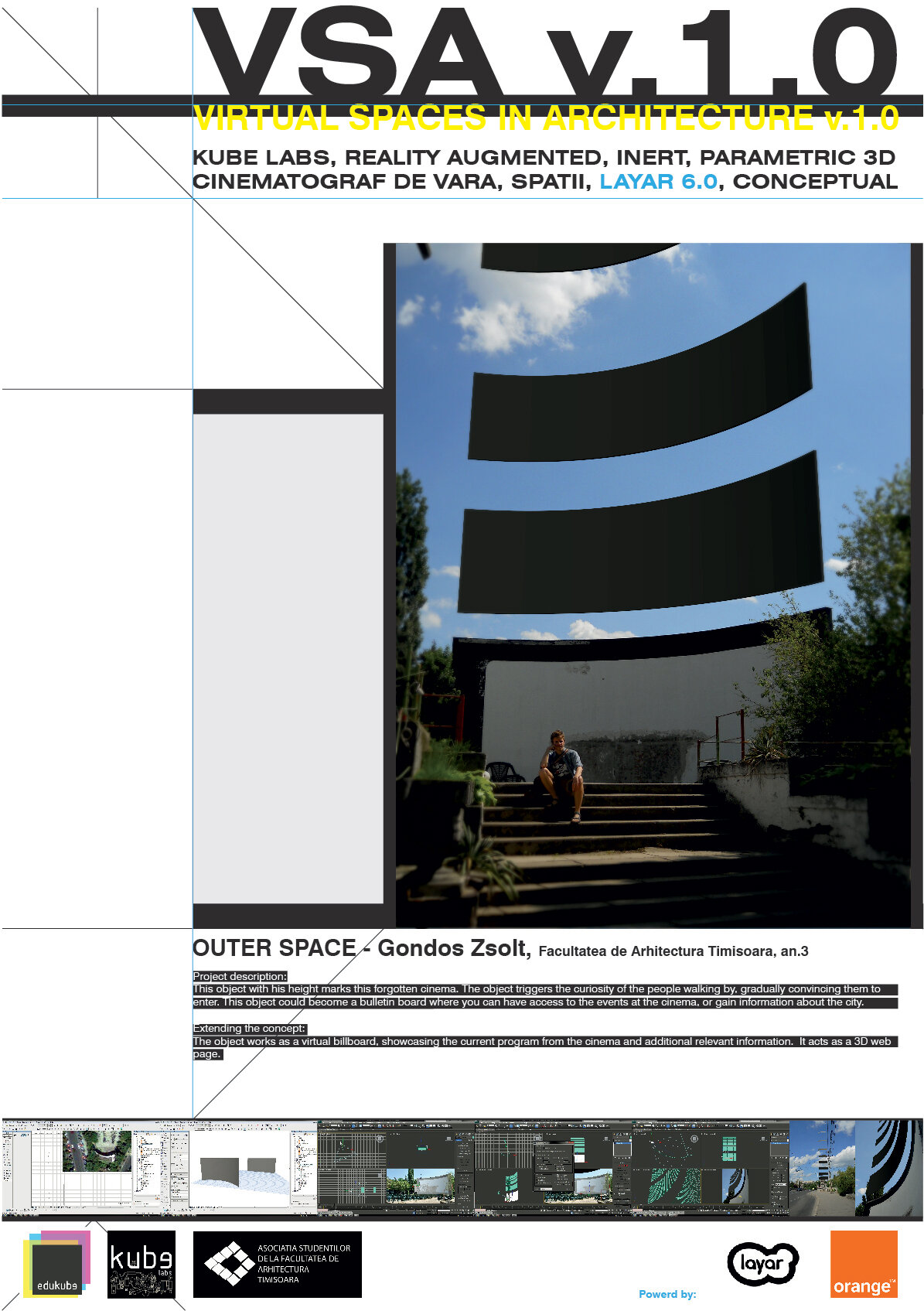

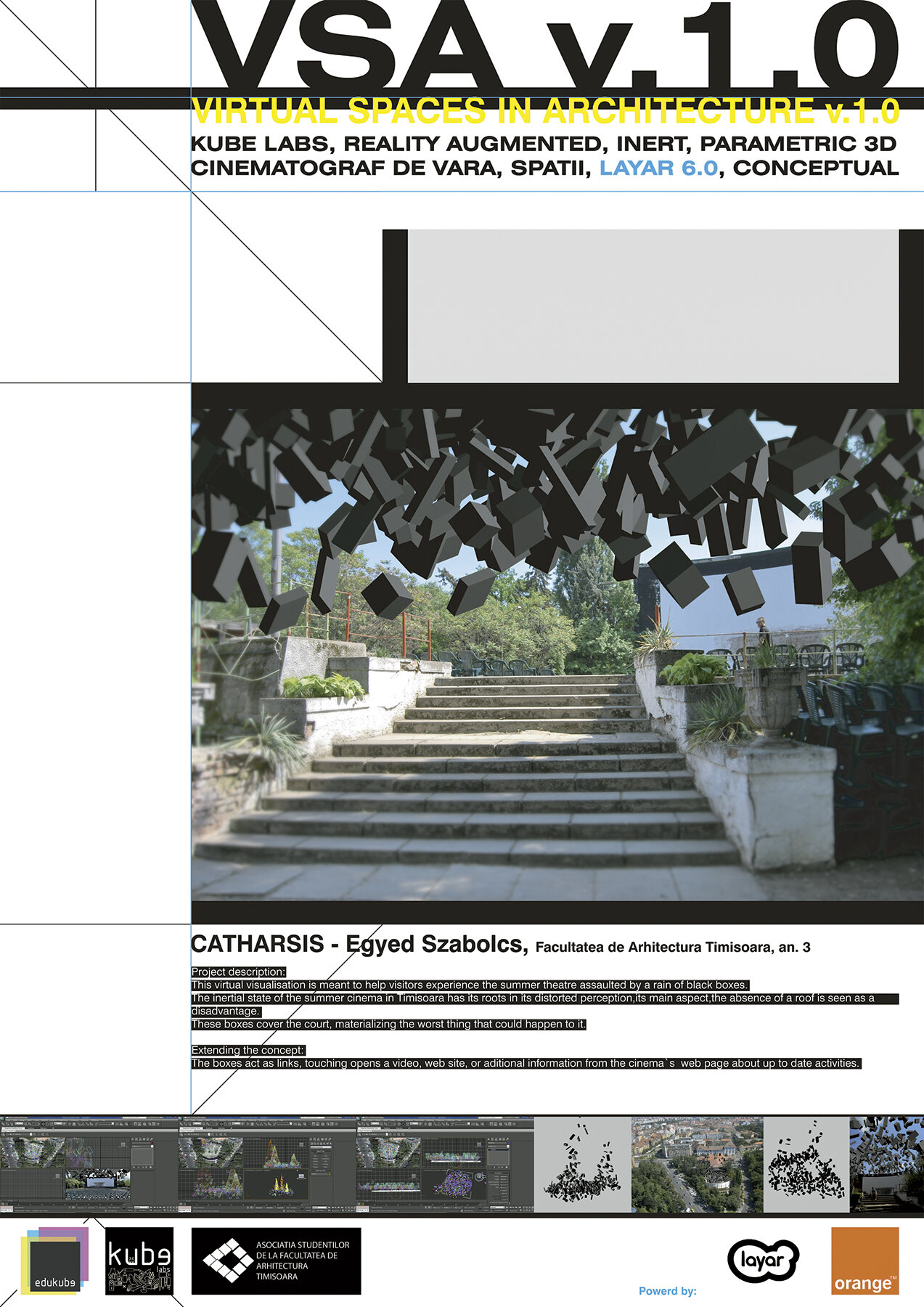

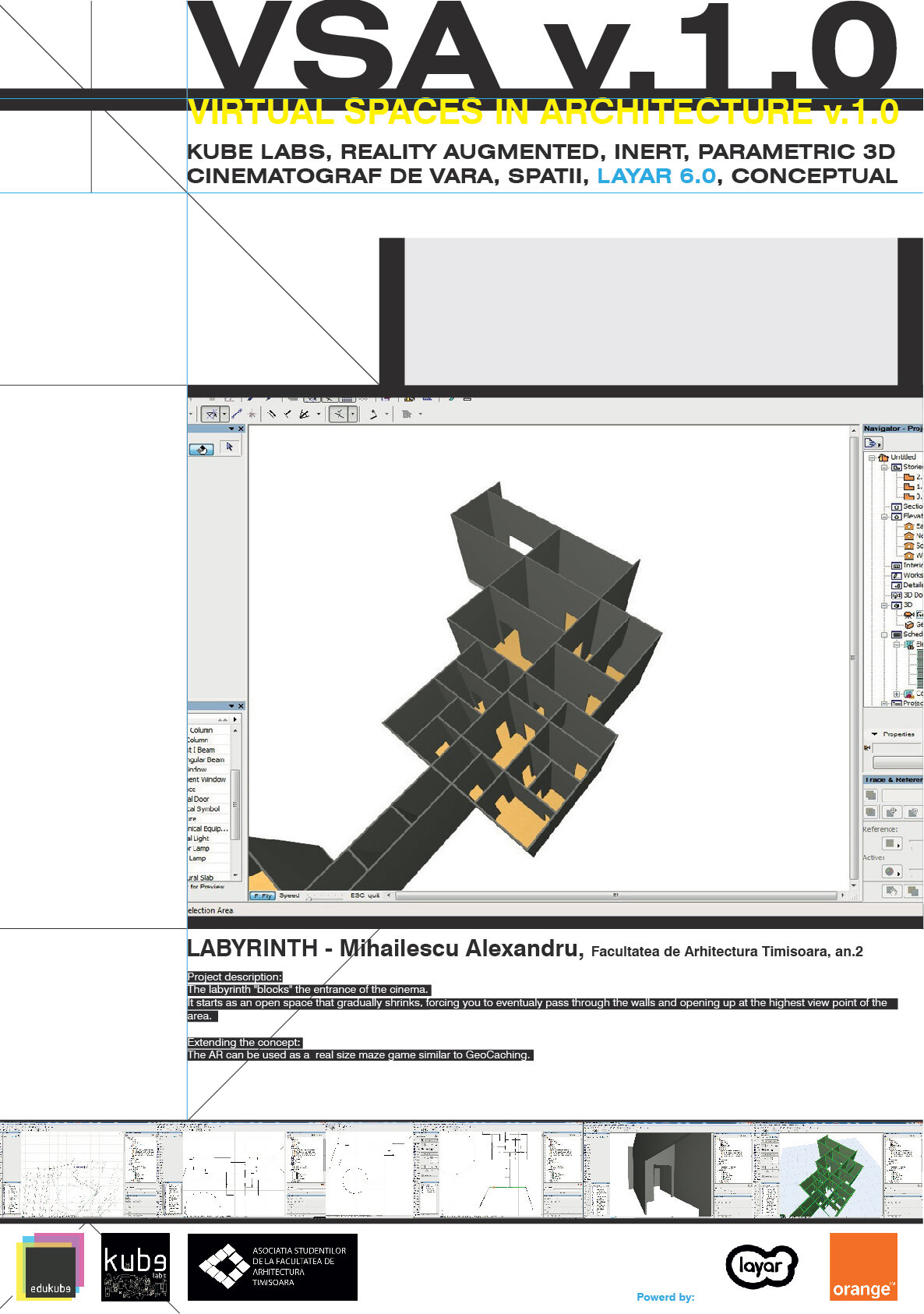

This has alienated architects and visual artists from this tool. Why leave this tool, unexplored by architects in their discourse, in the hands of advertising agencies? This was the premise of the Kube Labs workshop entitled Virtual Spaces in Architecture (VSA 1.0) organized by the Edukube team, made up of arch. Adriana Hanțiu, visual artist Alex Meseșan and Zoran Popovici, and with the participation of Alexandru Mihăilescu, Egyed Szabolcs, Zsolt Gondos from the Faculty of Architecture Timișoara, Georgianei Păunescu from UAUIM Bucharest and Irinei Tătăranu from the Faculty of Architecture "G.M. Cantacuzino" Iasi.

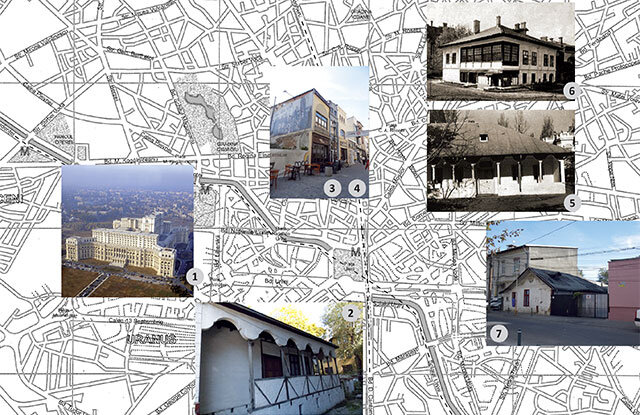

The location chosen for this workshop was an abandoned summer movie theater, thus providing the link between the interpretation of virtual space in cinematography and the current technological possibilities to create such spaces. If in cinematography Virtual Reality appears in the form of the real built environment broken from the actual context due to the altered focus of the camera and the sequences cut and recomposed so as to render a different reality than the one in which it was filmed, nowadays through mobile technology we have at our disposal the mobile phone screen which offers us the possibility to "see" another reality composed of information, interactive displays or three-dimensional volumes superimposed on top of the existing built environment. Can this technology change the way we perceive architecture in the same way that cinema can successfully alter an existing space and give it a changed role? Detective Rick Deckard's cramped block room in the movie Blade Runner (1982) was actually part of the spacious hallway of the Ennis Brown house designed by Frank Loyd Wright. Can we transform a real space in such a radical way using AR applications?

Starting from an analysis of the existing situation of the summer movie theater, hereafter referred to as layer 0, it was proposed to build two consecutive layers in order to generate a flow of people and data through the location. Layer 1 is the layer realizable with current technology, in the case of the present workshop, the AR service provided by the company Layar and populating the location with virtual 3D models at 1:1 scale in the form of architectural micro interventions. Layer 2 is a concept intervention pushing the potential of Augmented Reality and generating a remix of the boundaries between technology, architecture, game design, theater and new media art. The realized proposals come with a series of interventions in the site of the cinema extending the function of the real space. The extension of the projection screen with a series of slats comes with the conceptual role of an informational tower. One of the solutions proposes a virtual theater stage, located at the base of the projection screen, a stage that hypothetically can interact with the actors and is only visible on mobile phones or tablets. An experimental labyrinth that overlaps the existing path to a volume that represents the state of a cloud computer running animation and movie scenes. The workshop also revealed the current limitations of AR applications. The small number of surfaces for the 3D model to be uploaded to the internet poses a difficulty in designing this model. All solutions conceptually incorporated the possibility to interact with the volumes placed in the virtual environment. This interaction allows to modify the initial volumetry by "touching" different surfaces or the possibility to use the volumes as interfaces to access additional information from a database. At the moment, the Layar application does not allow such interaction, as the visitor is only presented with a series of volumes inserted into the location of the movie theater on the mobile phone screen.

The VSA 1.0 workshop also highlights the fact that 3D modeling programs have now moved beyond the role of a representational medium in architecture, providing a space for volumetric experiments in architecture, a detail that radically changes the way volumetric solutions are designed. Because a very important element in today's applications is the possibility to extract a series of statistics about the way of utilization we can come up with a series of figures related to the VSA 1.0 workshop. During the 2 weeks that the objects created in the workshop were online, they had a share of 2,450 visitors who activated this virtual layer and 378 people who visited the location to interact with the objects exhibited in the virtual environment.

Even if AR applications and volumes placed in the virtual environment do not have at this point the power of a movie set design, they can however offer sustainable and attractive solutions to take a public space out of inertia, being an avant-garde solution for micro interventions in architectural experiments.

1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cathedral_of_Our_Lady_(Antwerp)

2. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voronoi

3. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_Glass

4. http://spectrum. ieee.org/biomedical/bionics/augmented-reality-in-a-contact-lens/0

5. www. layar.com; www.wikitude.com

Acknowledgments:

Frank Wouters, cobalt123, McKay Savage, Kevin Adams and Bill Tyne for licensing the photos under the Creative Commons system.