Trans-fondul, trans-funcția și trans-forma

Inserții.

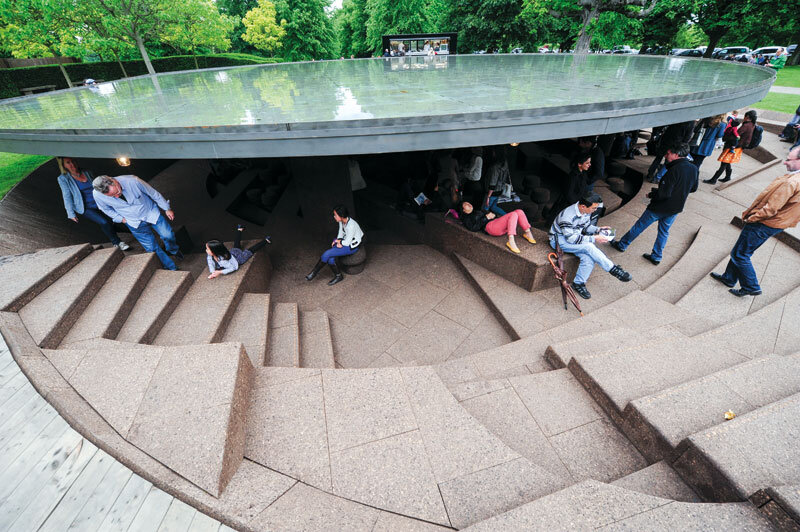

Sală de recitaluri la Troldhaugen, lângă locuința și muzeul Edvard Grieg

Insertions. Recital hall in Troldhaugen, near the Edvard Grieg house and museum

Trans-substance, trans-function and trans-form

| … Atunci broasca s-a transformat într-o prințesă frumoasă. Flăcăul s-a transformat într-o stană de piatră. Dr. Jekill s-a transformat în Mr. Hyde. Deșertul s-a transformat într-un minunat oraș cu o bogăție de lumini, iar bordeiul sărăcăcios într-un măreț castel cu o sută de turnuri. |

| Structura imaginarului în evoluție

Transformările spontane, radicale, unitare și univoce sunt nu doar cuvenite, ci sunt minunate în lumea spiritelor inocente și-n lumile imaginare. Dar tot un fel de inocență îndeamnă la astfel de soluții și în lumea reală. Așa cred eu, că năzuința către transformări miraculoase e conținută, în mod genuin, în chiar structura imaginarului omenesc. Apoi spiritul omului se cultivă, se nuanțează și se desprinde, mai mult sau mai puțin, de această pornire ingenuă. La fel se întâmplă și cu omul care s-a făcut arhitect. Sau nu se întâmplă. Spiritul acesta pe care ne place să-l numim imaginar e de două feluri. Unul e slobod și astral și se numește imaginație. Asociată cu o morală ma-niheistă, imaginația dă farmec și valoare basmelor. În arte, imaginația e combustia creativității, iar în arhitectură, când e mânuită de magicienii ei, face dintr-un spațiu o stare și dintr-o formă o trans-formă. Cu trans de la trans-cendent. Sau transă. Celălalt imaginar e o țesătură subtilă care se interpune între noi și realitate, țesătură care pare transparentă, dar de fapt creează imagini ce distorsionează discret realitatea - și ea sadic de complexă, nu-i vorbă. Prin urmare, chiar hrănite din realitate, imaginile despre realitate sunt structurate de imaginarul nostru și ne sunt proprii nouă. Pe acestea le chestionăm noi atunci când propunem modificarea locurilor prin arhitectura noastră. Ei, arhitecturii, îi mai spunem și amenajarea spațiului. Și tare ne mai place să amenajăm și să modificăm - că e sau că nu e nevoie. Așa de tare încât s-ar găsi printre noi destui dispuși să amenajeze și pădurile și munții, dacă i-ai lăsa (citește plăti). Cu trepte, cu băncuțe și poate și cu arteziene. Așa cum alții își amenajează malul mării până ce marea nu se mai vede decât pe Google Earth. Cu cât mai spre sud, cu atât mai abitir. Ai o potecă? Asfalteaz-o! Sau paveaz-o! Dar să fie o alee lată, să știi o treabă. Ai câțiva salcâmi lăsați de Dumnezeu? Rade-i! Eventual, pui în loc o lădiță cu tuia de la Hornbach. Ai o pantă? Pune-i imediat o mulțime de trepte! Din beton, se știe. Ai o cât de mică motivație în vârf? Arde-i un carosabil pân-acolo! Ai un iaz? Ori îl seci, ori îl betonezi, îl faci pătrat, îl faci bazin, faci „o compoziție” - ideea e să nu mai fie ce-a fost, dacă a încăput pe mâna ta. Ai puterea-n în pix, dacă ai și-n spate una în bani. Motivații se găsesc - și-ncă dintre cele mai convingătoare pentru publicul basmelor; ele sunt de tipul: te doare măseaua? Scoate-o și scapi de infecție; cu tratamentele, drumul e lung și complicat. Iar puterea asta demiurgică de a schimba prin câteva gesturi mari geografia, istoria, societatea… doar prin linii pe hârtie - ce dulce ispită e! Nu vorbesc de țările nordului, de exemplu, unde imaginarul colectiv e genetic altfel și nici de lumi în care e educat în alt spirit. Acolo, castelului îi este preferat bordeiul, pe care-l transformă doar cât să nu mai fie sărăcăcios. Și dacă e într-adevăr nevoie, potecii îi pun dale din pietre. Nu vor ei să „evolueze” și pace. Și doar au exemple în Dubai. Mai nou, în minunatul Baku. |

| Citiți textul integral în nr 3/2012 al revistei Arhitectura. |

| …Then the frog turned into a beautiful princess. The young man turned into a block of stone. Dr. Jekyll turned into Mr. Hyde. The desert turned into a wonderful city of countless lights, and the hovel turned into a magnificent castle with a hundred towers. |

| The evolving structure of the imaginary

Spontaneous, radical, unitary and unequivocal transfor-mations are not just appropriate but miraculous in the world of innocent spirits and imaginary worlds. But it is also a kind of innocence that urges such solutions in the real world. This is why I think that the striving toward miraculous transformations is genuinely contained in the very structure of the human imagination. The human spirit then cultivates itself, grows more subtle and, to a greater or lesser extent, breaks away from this ingenuous urge. The same thing happens to people who have become architects. Or else it doesn’t happen. The spirit we like to call the imaginary is of two kinds. One is free and astral, and is called the imagina-tion. Combined with a Manichean morality, the imagination lends charm and value to fairy tales. In art, the imagination is the combustion of creativity, and in architecture, when handled by a magician, it turns space into a mood and forms into trans-forms. Trans as in transcendent. Or trance. The other imaginary is a subtle weave that stands between reality and us, a weave that looks transparent, but which in fact creates images that subtly distort reality - a reality that is sadistically complicated, of that there can be no doubt. Consequently, although nourished by reality, images of reality are structured by our imagination and come from us. We interrogate them when we set out to alter places using our architecture. We also call architecture the development of space. And we love to develop and alter it, whether it needs it or not. We love it so much that, among us, there are plenty of architects that would be prepared to develop even the forests and mountains, if you let them (or paid them to), with steps, benches, and maybe even fountains. The way others develop the seashore, to the point that the only way you can see the sea is on Google Earth. And the further south the better. Got a footpath? Tarmac it! Or pave it! Make it a wide lane, if you want to do a good job of it. Got a few locust trees? Cut them down! You can always put a potted white cedar from Hornbach in their place. Got a slope! Make a flight of steps there this instant! Concrete ones, obviously. Got a pond? Either drain it, or fill it with concrete, or make it square, or turn it into a swimming pool, or make it part of some “composition” - the point is not to leave it the way it was when you first got your hands on it. The power is all in your pen, if you’ve got the financial backing. You’ll find reasons convincing enough for the fairy-tale-loving public, reasons that go like this: got a toothache? Get rid of the infection by having your tooth pulled out. Treatment is too lengthy and complicated. And this demiurgic power to change at a stroke geography, history and society, just by tracing lines on paper, is such a sweet temptation! I’m not talking about the Nordic countries, for example, where the collective imagination is genetic, or about worlds where it is educated in a different spirit. Over there, a hut that you can transform so that it isn’t as impoverished is preferable to a castle. And if there is really a need, then flagstones will serve for a path. They don’t want to “evolve” and that’s that. Even if Dubai and, more recently, wonderful Baku set them an example. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |

Inserții.

Sală de recitaluri la Troldhaugen, lângă locuința și muzeul Edvard Grieg

Insertions. Recital hall in Troldhaugen, near the Edvard Grieg house and museum

Inserții.

Sală de recitaluri la Troldhaugen, lângă locuința și muzeul Edvard Grieg

Insertions. Recital hall in Troldhaugen, near the Edvard Grieg house and museum

Înlocuiri (Atena) . Replacements, Athens

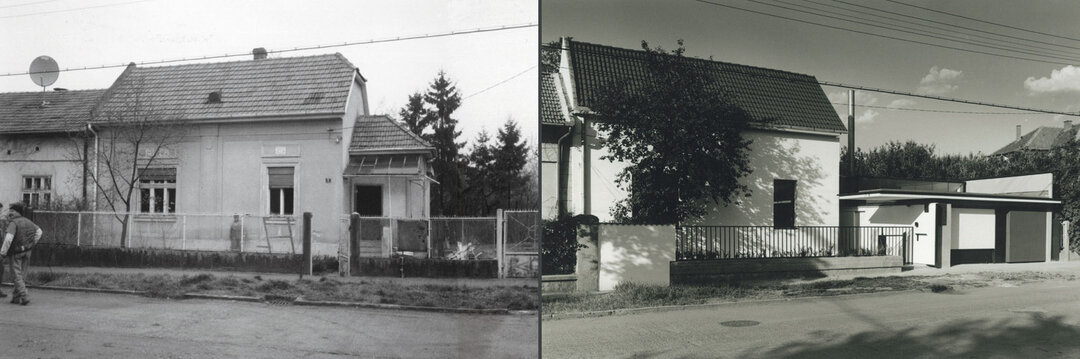

În capitala Germaniei, în era industrială, s-a construit ansamblul de locuit Hufeisen, Berlin-Britz, arhitect Bruno Taut.

Vara lui 2006 a fost una toridă,

în care iazul a secat mult.

In the capital of Germany, in the industrial age, the Hufeisen, Berlin-Britz residential complex was built by architect Bruno Taut.

The summer of 2006 was torrid and much of the pond dried up.

Amenajare carosabil la complexul muzeal Heatherland,

coasta de vest a Norvegiei.

Road rearragement in Heatherland,

Norwegian west coast

Amenajare pe Aeropagus, Atena

Development work, Areopagus, Athens