Judecata publică

Public Judgement

| În octombrie 2012, în timpul unei prezentări care a avut loc la a.pass (un institut pentru studiul avansat al performance-ului din Bruxelles) în cadrul rezidenței artistice Thematics - Come Together organizată de Bains Connective Art Laboratory, Rana Hamadeh, performer și artist vizual, originară din Beirut, dar activă în Olanda, a propus studiul unor fragmente selectate din volumul Sfera publică și transformarea ei structurală. Studiu asupra unei categorii a societății burgheze, al lui Jürgen Habermas. |

| Topica discuției era dată de contextualizarea termenului de public din perspectivă istorică, oferind idei despre descendența termenului cu scopul de a-l valoriza. Participanții la discuție au fost: Sara Manente (artist-performer din Italia, activă în Belgia), Lilia Mestre (artist-performer și coordonator artistic al Bains Connective Art Laboratory din Bruxelles), Anca Mihuleț (critic de artă și curator la Galeria de Artă Contemporană a Muzeului Național Brukenthal din Sibiu), Constantina Peter (intern la Bains Connective Art Laboratory din Bruxelles) și Delia Popa (artist vizual care lucrează în principal cu performance, instalații video și text).

În introducere, Rana Hamadeh interoghează termenul de public - nu neapărat ca sferă publică, spațiu public sau public în dihotomia public-privat - ci, mai degrabă, cu intenția de a analiza ce poate fi numit public. Artista conturează câteva întrebări care decurg din con-ceptul de „public”: din ce poziție ne raportăm la public? Ce reprezintă noțiunea de „public” în afara dihoto- miei public-privat? Care sunt incluziunile și excluziunile acestui termen și sub ce termeni poate fi înscris cineva în ceea ce este public? Cine este înscris în public - este termenul de „public” specific unui „noi” care este în relație cu cetățenia? Iar ceea ce este în afara acestui „noi” poate fi înscris sau nu termenului de „public”? Cine are dreptul de intrare către public, fie că vorbim aici despre sfera publică, domeniul sau spațiul public? Rana Hamadeh abordează noțiunea de „public” pentru a scutura, pentru a cauza un mic cutremur în jurul ideii, care primește astfel conținut și posibilități de interpretare - este public ceea ce se află în afara unei încăperi cu ziduri? Aparține de domeniul public ceea ce se numește instituție publică în interiorul unui stat? În textul său, Jürgen Habermas a analizat prima referință etimologică la sfera publică. În limba germană, substantivul Öffentlichkeit s-a format de la adjectivul öffentlich în decursul secolului al XVIII-lea, dar aproape că nu era utilizat în acea perioadă, ceea ce îl putea determina pe Heynatz să îl considere neplăcut. Cum ideea de „public” nu impunea o terminologie specifică, putem presupune că, cel puțin în Germania, sfera publică a apărut și a intrat în posesia funcțiunilor sale doar în acel moment. Se poate observa o preocupare pentru reprezentarea „publicului” și a „privatului” în Antichitatea greacă, atunci când, în competiția dintre egali, cel mai bun excela și câștiga imortalitatea faimei; polis-ul furniza un teren deschis pentru distincții onorabile: cetățenii interacționau ca egali cu egali, însă fiecare făcea ceea ce putea mai bine ca să exceleze. În contextul identificării istorico-etimologice a termenului de „public”, Rana Hamadeh consideră că publicul nu a fost niciodată deschis pentru toți. Ce ar putea reprezenta acest fapt - este deschiderea un criteriu pentru „public”? Ce implicații ar avea această deschidere? Delia Popa menționează că atunci când se afirmă că ceva este deschis pentru toți înseamnă că sunt sectoare închise. Lilia Mestre chestionează ideea de „toți” - cine sunt „toți”? „Toți” reprezintă un concept imposibil. Rana Hamadeh aduce în discuție un film lansat la începutul acestui an de către artista olandeză Wendelien van Oldenborgh, a cărei activitate de cercetare este concentrată în Brazilia. Acolo a lucrat cu două femei provenind din generații diferite - una dintre ele era în vârstă de 30 de ani, iar cealaltă avea 60 de ani. Femeia de 60 de ani era politician și era albă, iar cea de 30 de ani era cântăreață de muzică funk și era de culoare. În film, femeia politician îi spune tinerei că, în anii ’70, guvernul se manifesta împotriva ei. Printre altele, amintește de un anumit eveniment la care a participat toată lumea. În același timp, cântăreața vorbește despre un concert care a avut loc în ghetou și la care a venit toată lumea1. Dintr-o dată se simte o tensiune - cine este „toată lumea”? Cine sunt „toți”? Amândouă insistau că a venit toată lumea din țară. Dar acest corp comun care pentru ele reprezenta pe „toată lumea” consta în persoanele cu care ele se identificau la nivel de clasă socială. În acest sens, întrebarea despre un public deschis către toți depășește nivelul la care statul sau sistemul capitalist propun accesibilitate publică către instituțiile publice; discursul puterii într-o cultură a efortului reconfigurează forțele sociale și aduce în față modele excepționale. Lilia Mestre adaugă faptul că accesibilitatea este elastică, și nu o condiție generală; accesibilitatea este variabilă, generând spații care sunt mai mult sau mai puțin flexibile. Accesibilitatea este un instrument, un spațiu pe care cineva poate să îl revendice. Rana Hamadeh se gândește că ideea de accesibilitate merge mai departe de capacitatea de a accesa sau nu o instituție; putem vorbi despre accesibilitate în fața cunoașterii. Sau accesibilitate pentru a deveni cetățean, concluzionează Lilia Mestre. Rana Hamadeh se întreabă dacă „public” este un termen legat doar de accesibilitate. Anca Mihuleț reflectează asupra condiției de „public”, care poate reprezenta un spațiu al consensului, un spațiu fără competiție unde nu există tensiunea ca unul să devină mai bun decât celălalt. Pentru Lilia Mestre, spațiul public este un loc al dezacordului, un loc în care nu există consens, dar există posibilitatea de coexistență. Și aceasta deoarece nu ne confruntăm cu revendicări, chiar în ceea ce privește descrierea noțiunii, și nu există autoritatea bunului-simț. Sara Manente pune accentul pe „lucrul public”, „res publica” - atunci când publicul interacționează cu guvernul, cu legea, și această stare este consens și dezacord în același timp. Habermas a scris că, în timpul evului mediu, categoriile de public, privat și sferă publică cunoscute ca „res publica” serveau ca proprie interpretare politică, dar și ca instituționalizare legală a unei sfere publice care putea fi percepută ca fiind burgheză. Pentru uzul comun exista acces public la fântână și la piața centrală - loci communes, loci publici. Particularul era opus comunului; înțelesul special al privatului sau particularului era corelat cu interesele private. Mai târziu, în secolul al XIX-lea, spune Rana Hamadeh, cafenelele și ceainăriile erau spațiile publice în care oamenii se puteau întâlni și consuma ceai; aceste activități erau relaționate cu comerțul de ceai, cu descoperirea ceaiului, cu aducerea ceaiului din Asia și cu atitudinea față de acest produs exotic. Într-o oarecare măsură, constituirea evenimentului public, al momentului și al spațiului alături de statul în public erau condiționate de o istorie a schimbului comercial, parte a istoriei coloniale. În ceainării se găseau ziare, acolo era locul de întâlnire al scenei intelectuale și se desfășurau discuții publice despre politica statului. Publicul era în aceeași măsură clasă și context. Un alt aspect legat de modul în care ajungem la termenul „public” este folosirea transparenței în relație cu viața publică la nivel politic și social. Constantina Peter întreabă dacă un guvern poate fi cu adevărat transparent, în timp ce Delia Popa vede diferitele niveluri de transparență ca valori ale statului democratic. Punând în legătură transparența cu un discurs politic care creează iluzia deschiderii și a locurilor disponibile pentru toată lumea, Rana Hamadeh consideră transparența ca fiind un concept periculos, în timp ce democrația poate fi percepută ca o altă formă de dictatură mascată de iluzia transparenței. În acest caz, pornind de la seria de interviuri dintre Gilles Deleuze și Claire Parnet intitulată Abécédaire, Sara Manente dezbate asupra ideii de jurisprudență, accentuând necesitatea aplicării legii asupra felului în care guvernul funcționează în practică. În egală măsură, ea amintește capitolul „Tiananmen” din cartea lui Agamben, Comunitatea care vine, în care autorul prevede că viitorul democrațiilor noastre este un stat împotriva oamenilor pentru că nu va mai exista reprezentabilitate, ci comunități stratificate, iar oamenii nu se vor putea integra într-o comunitate care să fie unanim recunoscută. Urmând aceste idei, Rana Hamadeh combate ideea că spațiul public ar trebui iden-tificat cu un spațiu al consensului; consensul nu oferă dreptul de intrare către domeniul public. Pentru artistă, noțiunea de „public” definește un domeniu care permite acceptarea diferenței, alături de vizibilitatea disputelor și a ciocnirilor implicate în producția diferenței. Lilia Mestre afirmă că, atunci când nu există dife- rențe de opinie, nu există practică - dacă sunt diferit de tine, aș vrea să negociez. Dacă nu există negociere, nu există public. Pentru Rana Hamadeh, negocierea generează „publicul”. Acesta nu este un spațiu. Dacă ne gândim la public în afara spațiului sau a domeniului, el devine o mișcare, o forță care descompune normele în fiecare secundă. Noi negociem și performăm (după cum formulează Delia Popa) propriul nostru limbaj pentru a reinventa sfera publică. Angajamentul în fața publicului poate să aducă idealizarea a ceea ce semnifică cu adevărat noțiunea de „public”. Cererea socială pentru spațiu public poate accelera procese incerte, aducând cu sine instituția criticii care implică deschidere, dreptul la cunoaștere și înțelegere, împreună cu condiția ochiului public sau a observatorului. |

| 1. Artista vorbește despre filmul Bete & Deise (2012), al lui Wendelien van Oldenborgh (artistă care lucrează la Rotterdam). Cele două personaje sunt Bete Mendes (o figură politică și actriță de telenovele) și Deise Tigrona (o faimoasă cântăreață de Funk Carioca); ele se întâlnesc într-o clădire în construcție din Rio de Janeiro și comentează asupra ideii de voce publică. Filmul confruntă privitorul cu juxtapunerea dintre sfera publică și existența personală. |

| In October 2012, during an artist-presentation taking place at a.pass (an institute for advanced performing training in Brussels) in the frames of the artistic residency Thematics - Come Together organized by Bains Connective Art Laboratory, Rana Hamadeh, a performance and visual artist from Beirut currently working in the Netherlands, proposed to comment upon a series of fragments selected from Jürgen Habermas's book, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. |

| The topic of the discussion was contextualizing the term public from a historical point of view, giving some ideas from where the term descends, so that it is not taken for granted. The participants were: Sara Manente (an Italian performance artist based in Belgium), Lilia Mestre (performance artist and artistic coordinator at Bains Connective Art Laboratory in Brussels), Anca Mihuleț (art critic and curator at the Contemporary Art Gallery of the Brukenthal National Museum in Sibiu), Constantina Peter (intern at Bains Connective Art Laboratory in Brussels) and Delia Popa (visual artist working primarily with performance, video installation and text).

In her introduction, Rana Hamadeh questions the term public - not necessarily as public sphere, public space or public in its dichotomy towards private but more likely trying to think about what can be public. The artist considers that several questions arise from the concept of “public”: from which position do we think about public? What is public regardless the dichotomy public - private? What are not only the inclusions and exclusions from this term, but under what terms can somebody be inscribed within what can be public? Who is inscribed within the public - is the term “public” specific to an “us”, which is related to citizenship? And what is outside this “us”, can it be inscribed or not within this term of “public”? Who has the right of entry towards the public, be it the public sphere, the public domain or space? Rana Hamadeh is approaching the notion of public in order to shake, make a little earthquake of the term so it receives content and the possibility of interpretation - is anything outside a room with walls public? Is anything that is called public institution within a state belonging to the public realm? In his text, Jürgen Habermas analyzed the first etymological reference to the public sphere. In German, the noun Öffentlichkeit was formed from the adjective öffentlich during the 18th century, but it was minimally used in those days that Heynatz could consider it objectionable. As the idea of “public” didn’t impose a specific terminology, it can be assumed that at least in Germany, the public sphere emerged and took on its function only at that time. Notions concerning what is “public” and what is “private” can be found in the Greek historical times, when in the competition among equals, the best excelled and gained their essence - the immortality of fame; the polis provided an open field for honourable distinctions: citizens interacted as equals with equals, but each did his best to excel. In this kind of historical - etymological tracing of the term “public”, Rana Hamadeh considers that the public has never been opened to all. What would this signify - is openness a criteria for being “public”, and what would this openness imply? Delia Popa mentions that when you say something is opened to all, it means that there are a lot of areas that are closed. Lilia Mestre questions the idea of “all” - what is “all”? “All” is an impossible concept. Rana Hamadeh brings into the discussion a film launched at the beginning of this year by the Dutch artist Wendelien van Oldenborgh who has been researching a lot in Brazil. There, she worked with two women - one woman was around 30 years old, and the other one was about 60 years old. They came from different generations. The 60 years old woman was a politician, and she was white. The 30 years old woman was a funk singer, and she was black. In the film, the politician was telling the young woman about how in the ’70s, the government was standing against her. She was talking about a specific event attended by everybody. At the same time, the singer was talking about a concert that happened in the ghetto, where everybody came1. All of the sudden, there was this tension - who is this “everybody”? Who is this “all”? They both insisted that everybody in the country came. But the “everybody” they thought represented “everybody” were the persons they class-wise identified with. In this sense, the question about a public opened to all surpasses the level of what the state or the capitalist system can bring forth as a positive thing - that we have public accessibility to the public institutions; the power of discourse in a culture of effort reconfigures social forces, and brings forward exceptional models. Lilia Mestre adds that accessibility is elastic, it is not a generality; accessibility is variable, generating spaces that are more or less flexible. Accessibility is a tool, a space that one can claim. Rana Hamadeh thinks that the idea of accessibility goes beyond whether you can access or not an institution; we can talk about accessibility to knowledge. Or accessibility to be a citizen, as Lilia Mestre concludes. Rana Hamadeh asks herself whether “public” is a term linked only to accessibility. Anca Mihuleț reflects upon the condition of “public” that can represent a space of consensus, a space with no competition where you don’t have the tension of one becoming better than another. For Lilia Mestre, the public space is a place of disagreement, a place where there is no consensus, but there is the possibility of coexistence. Because there is no claiming, even in terms of its description, and there is no authority of the common sense. Sara Manente emphasizes the idea of the “public thing”, “the res publica” - when public interacts with the government, with the law, and this state is consensus and disagreement at the same time. Habermas wrote that throughout the Middle Ages, the categories of the public, private and the public sphere known as “res publica” served as the political self-interpretation, as well as the legal institutionalization of a public sphere that could be perceived as bourgeois. For common use there was public access to the fountain and market square - loci communes, loci publici. The particular was opposed to the common; the special meaning of private or particular was connected to private interests. Later on in the 19th century, Rana Hamadeh says, the café and tea house were public spaces where people could meet and drink tea; it was very much related to the trade of tea, the discovery of tea, bringing tea from Asia, and dealing with this exotic good. In a way, the constitution of the public event, moment, and space, and sitting in public were conditioned by a history of trade that was also part of a colonial history. In the tea houses there were journals, there was an intellectual scene, there were public discussions about public affairs. Public was both class, and context. Another aspect related to how we arrive to the term “public” is the usage of transparency in relation to publicness. Constantina Peter asks if a government can be completely transparent, while Delia Popa sees the different levels of transparency as assets of the democratic state. By connecting transparency to a political discourse that has created the illusion of openness and of place available for everyone, Rana Hamadeh considers transparency as a dangerous concept in itself, while democracy can be perceived as another form of dictatorship masqueraded with the illusion of transparency. In this case, starting from the Abécédaire interviews between Gilles Deleuze and Claire Parnet, Sara Manente debates upon the idea of jurisprudence, stressing out the application of law upon the way the government functions in practice. She reminds of the chapter “Tiananmen” from Agamben’s book The Coming Community, where the author foresees that the future of our democracies is a state against the people because there is no more representability, but layered communities, and the people won’t be able to integrate themselves in a unanimously recognized community. Following these ideas, Rana Hamadeh disagrees that public space should be identified with a space of consensus. She disagrees that consensus is the tool that gives the right of entry towards the public domain. For her, “public” is a domain that allows the emergence of difference, and that allows the visibility of the struggles and clashes involved in the production of difference. Lilia Mestre states that if there is no dissensus, there is no practice - if I am different from you, I would like to negotiate. If there is no negotiation, there is no public. For Rana Hamadeh, this negotiation generates “the public”. The public is not a space. If we think about public outside space or domain, the public becomes a movement, a force that undoes the norms every single second. We are negotiating and performing (as Delia Popa puts it) our language in order to reinvent the public sphere. The commitment to the public can bring in itself the idealization of what public really means. The social demand for public space can accelerate processes that are uncertain, bringing along the institution of critique that involves openness, the right to know, and understand, and the condition of the public eye or observer. |

| 1. The artist is talking about Wendelien van Oldenborgh’s (visual artist based in Rotterdam) film Bete & Deise (2012). The two characters are Bete Mendes (political figure and telenovela actress) and Deise Tigrona (famous Funk Carioca singer); they meet in a building under construction in Rio de Janeiro, commenting upon the idea of public voice. The film confronts the viewer with the juxtaposition of public sphere and personal existence. |

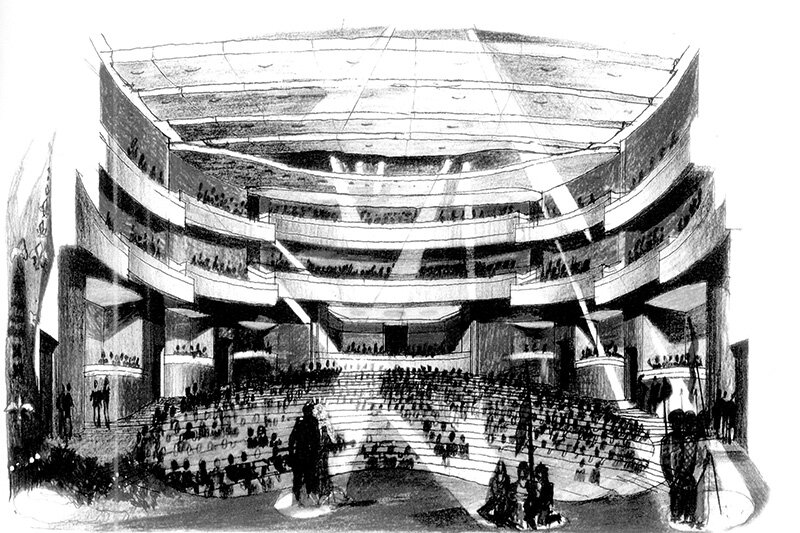

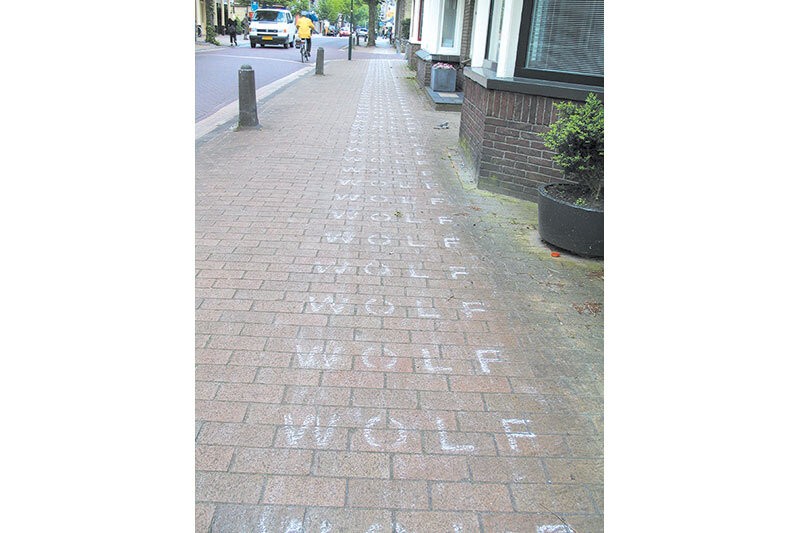

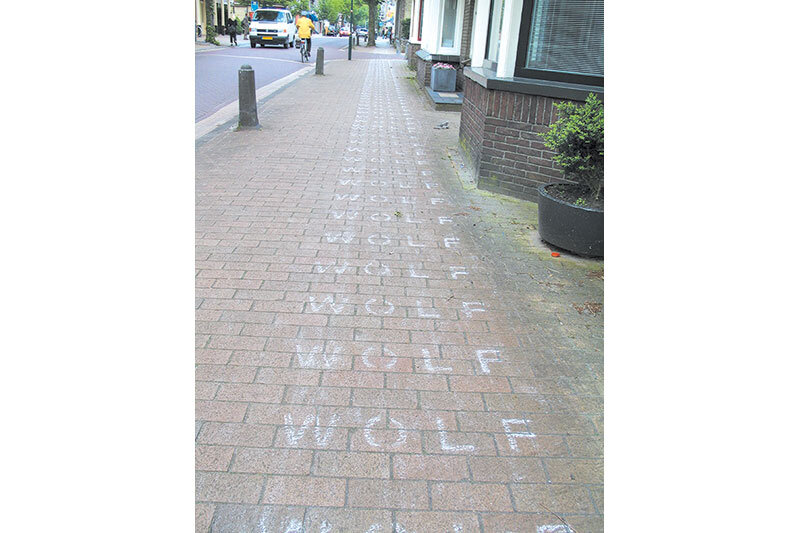

Rana Hamadeh - Primul salon (Het Eersteschilderijenzaal/ The First Drawing Room), performance în Muzeul Teylers, unde artista a prezentat un desen al salonului realizat la mijlocul secolului al XIX-lea, care este identic cu imaginea camerei de astăzi. Image courtesy: artista.

Rana Hamadeh - Het Eersteschilderijenzaal/ The First Drawing Room, performance in Teylers museum, where the artist shows a drawing made of the Drawing Room in the mid 19th century, which is identical to the room today. Image courtesy: the artist.

Rana Hamadeh - Primul salon (Het Eersteschilderijenzaal/ The First Drawing Room), performance în Muzeul Teylers, unde artista a prezentat un desen al salonului realizat la mijlocul secolului al XIX-lea, care este identic cu imaginea camerei de astăzi. Image courtesy: artista.

Rana Hamadeh - Het Eersteschilderijenzaal/ The First Drawing Room, performance in Teylers museum, where the artist shows a drawing made of the Drawing Room in the mid 19th century, which is identical to the room today. Image courtesy: the artist.