Locul public

The public space

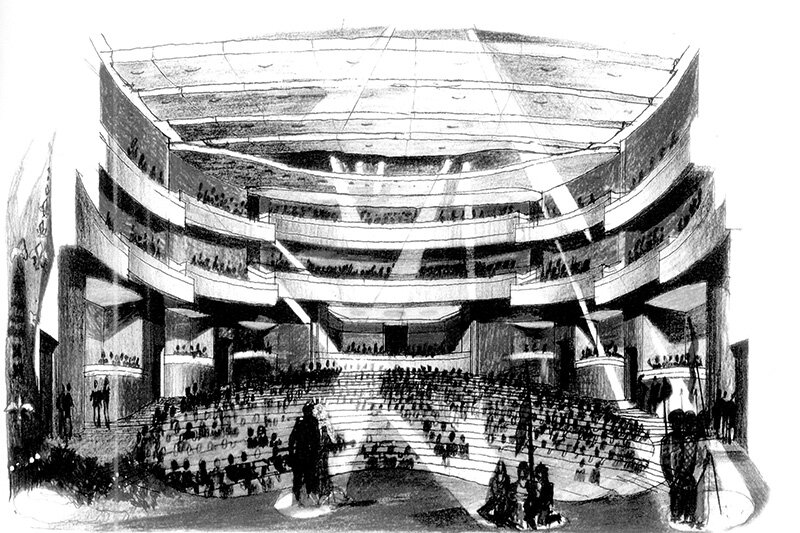

| Locul public începe să fie deîndată ce, în afară de mine, mai apare și altcineva pe un teritoriu dat și, astfel, există posibilitatea ca nu numai să privesc împrejurul meu, dar, în același timp, să și fiu eu însumi privit. Înspațierea evenimentului de a privi și de a fi privit este nivelul elementar al locului public. |

| Un asemenea loc, odată folosit în scopul arătat mai sus, trebuie să se plieze înapoi în vag, în starea pre-formată a spațiului. Acest loc urmează să existe numai atât timp cât există evenimentul care își inventează spațiul necesar, aura în care se va petrece, în felul în care și obiectele își inventează propriul spațiu.

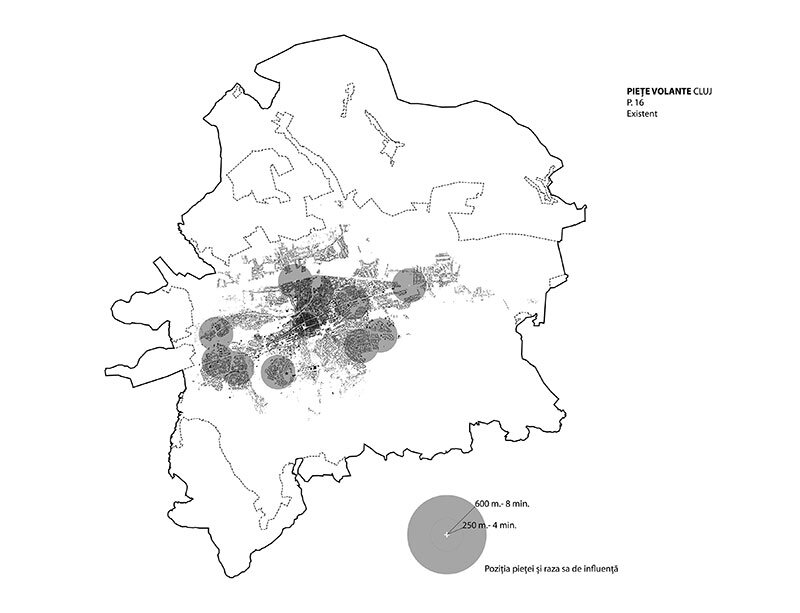

Evenimentul este aici înțeles ca un sistem de relații dinamice, în care vizibilitatea joacă rolul esențial, care se stabilește la un moment dat (și pentru o perioadă determinată) între cel puțin două ființe umane. Evenimentul „are loc”, așadar extrage cu sine, depliază spațiul întâmplării sale - locul public. Loc public > spațiu public Motivul pentru care în acest text se folosește cu precădere sintagma loc public derivă din modul în care acesta este definit mai sus: atributul de a fi public presupune cu necesitate ca „înscenare” spațială doar o întindere, iar nu un spațiu de/limitat (prin felurite mijloace ale construcției, dar și prin alegerea unui loc natural împrejmuit)1. Cuvântul loc indică aici faptul că există doar o cerință spațială minimală pentru înființarea, pentru întâmplarea unui eveniment public, o suprafață limitată. Limitele locului sunt date de chiar anvergura eveni-mentului în deplierea sa, iar nu de gesturi de edificare prealabile: evenimentul scoate acea porțiune de spațiu din spatium, iar nu zidirea; aceasta din urmă, cu condiția de a rămâne minimală și joasă (tocmai spre a nu impieta vizibilitatea reciprocă) poate veni ca o consecință, ca o constatare a unei recurențe a unui anumit eveniment într-o localizare dată, iar nu ca o precondiție de natură să „invoce”, să „lubrifieze” apariția evenimentului. În locul public se pot petrece deodată, coexistând pe un același teritoriu, evenimente de felul negocierilor pe care acest schimb de vizibilități îl face posibil (comerț, decizie comună2) sau al înfruntării (câmp de bătălie, spațiu al pedepsei). Sunt acțiunile care se petrec „pe față, la lumina zilei, în opoziție cu procedurile secrete” - (Vernant, 1995, 70). Regimurile de autoritate, despre al căror raport cu locul și cu locurile publice va fi vorba altundeva, au tendința să controleze integral3 această depliere în deschis a evenimentului sau, cum formulează Lyotard, „să țină evenimentul sub autoritatea (birocrației totalitare)” - (Lyotard, 1997, 83). E nevoie însă doar de a fi întrezărit caracterul virtual al unui loc natural și de puțină amenajare pentru ca el să se lumineze prin actul evenimentului, prin vizibilitate. Cu alte cuvinte, pentru ca un loc să devină loc public este suficient „luminișul”, nu este nevoie neapărată de Raum. Raum poate deveni ulterior edificat, deși luarea lui în posesie temporară de către migratori pentru așezarea taberei nu necesită decât o sumară degajare și ordonare a sa. Unii antropologi, precum Angelo Moretta, sau chiar arheologi, precum François de Polignac, explică chiar apariția localităților prin gruparea în jurul câte unui sit „luminat” de evenimente, de regulă sacre, „la cité cultuelle” (cum îl numește De Polignac), prin fortificare, geometrie interioară, construire în interiorul limitelor. Un domeniu al locuirii, așadar, care, prin tocmai calitatea sa de a se petrece în vecinătatea celuilalt, garantează cumva frecvența unor întâlniri care, ele, abia reușesc să garanteze autosusținerea ca eveniment a „luminișului” inițial q.e.d. loc public. Concluzia acestei amenajări minimale de care are nevoie locul pe care evenimentul public este pe cale de a se întâmpla va fi, desigur, dezamăgitoare pentru arhitecți, care au crezut multă vreme că rețeta spațiului public este una geometric cuantificabilă și că aceasta ține de rigoarea cu care ei vor fi proiectat spațiile „civice”: monumente, edificii, eroism împietrit. Or, dimpotrivă: adeseori se observă că rețeta locului public este mai evanescentă decât au crezut ei și că le-a scăpat bunăoară arhitecților români ai deceniilor șapte, opt și nouă, care au construit „centre civice” în fiece capitală de județ după formule vulgarizate (și, foarte important, laicizate!) ale forum-ului roman, sacrificându-se în proces centrele reale ale respectivelor orașe (devenite municipii). Poate exista Loc public neconstruit, pe care privirea poate baleia nestânjenită, așa cum este cazul ringului de dans deja amintit (locul unde se petrece hora duminicală în satul românesc, de pildă), al unui câmp de bătălie sau, mai frecvent, al unei piețe publice. Habermas insistă chiar asupra faptului că „viața publică, bios politikos, se desfășoară în piață, în agora, fără să fie însă în vreun fel legată de acest loc anumit. Sfera publică se constituie în cadrul vorbirii (lexis), care de asemenea poate lua forma unei consfătuiri sau a unei judecăți, la fel ca în cazul unei acțiuni comune (praxis), cum ar fi conducerea războiului sau a jocurilor războinice” (1998, 47). Rem Koolhaas a criticat frontal această obsesie demiurgică pentru spații civice stabile, edificate și complet controlate pe care doresc să le instituie arhitecții în orașe, în cartea sa Conversations with Students (1996). Deși nu o formulează ca atare, concluzia lui Koolhas pare să fie aceea că atributul de a fi locuri publice nu presupune o prealabilă intervenție edificată și, viceversa, prin simplul fapt că au amenajat un anumit spațiu și l-au denumit „civic”, sau „public”, sau „loc de întâlnire” nu înseamnă cu necesitate că ele vor și fi folosite ca atare de către membrii unei comunități. Locul public dă seama despre identitatea colectivă Identitatea de grup (colectivă, locală sau regională care aparține unei comunități etnice etc.) este exprimată elocvent de modul în care este făcut vizibil, administrat și folosit Locul public și, mai ales, de relația Loc public-Spațiu privat. Acest mod este o funcție de timp, nu este dat și imuabil, deci are caracter procesual și are, de asemenea, o istorie specială a propriei deveniri. Schimbarea regimului de proprietate asupra terenurilor este la fel de influentă asupra identității raportate la folosirea spațiului comun ca și modificările culturale sau psihologice (pe care, de pildă, le analizează proxemica) sau cele social-politice (i.e. depinzând de accentul pus pe individ sau pe colectivitate, bunăoară). Identitatea, așa cum este ea prezentată de înspațierea și, mai ales, de înzidirea relației, devine lămuritoare doar atunci când este exprimată nu în termeni absoluți, ci în grade de comparație. Identitatea este un atribut al localului, al vecinătății și este o problemă de grad, iar nu o diferență de rang. Christian Norberg Schulz accepta diferențele de caracter (incluzând gradele de ordonare) care pot exista între un obiect, arhitectura și locul căruia îi aparține sau între loc și localitate ori zonă în ansamblu, în termenii topologiei. Dacă discutăm despre arhitectura rurală a unui aceluiași teritoriu populat de etnii diferite (Transilvania sau Dobrogea sunt două exemple lămuritoare în această privință), vom putea institui diferențe locale, moleculare, devreme ce factorul climatic și de relief se simplifică; ceea ce rămâne este așadar diferență culturală. Numai în astfel de „unități de vecinătate”, în insule de proximitate comparabile poate fi purtată o discuție relevantă despre identitatea exprimată prin arhitectură. Alte tipuri de comparații îndepărtate, de pildă, cele făcute între arhitectura vernaculară din unele zone românești și unele insule ale Japoniei - un gest propriu anilor șaptezeci și optzeci autohtoni, când părea că exemplul japonez al devenirii fără ruptură dinspre tradiție către modernitate poate fi reconciliat cu retorica național-comunistă românească - devin complet nerelevante și sunt, probabil, mult îndatorate similitudinilor de climă, relief, izolare. O abordare în cadre locale și regionale, din perspectiva diferitelor aspecte de gestionare a unei geografii similare, este așadar calea de urmat în discuția despre identitate. Identitatea se instituie prin procese de asimilare și refuz ale unor modele concurente pe un același teritoriu sau între teritorii proxime. Un exemplul elocvent asupra acestei viziuni comparatiste moleculare asupra identității ni-l dă, în mod paradoxal, Blaga, dar nu prin conceptul de „matrice”; dimpotrivă, printr-un articol marginal în opera sa din Cuvântul 2 (274) / 4 octombrie 1925. Textul lui Blaga ne sugerează că identitatea este dată în mod esențial de modul de configurare și utilizare a Locului public, de raporturile de deschidere sau de excludere reciprocă ale insulelor de Spațiu privat - totdeauna însă în raport cu Locul public - acest teritoriu al învecinării făcute vizibile. Știm cât de diferit este caracterul orașelor săsești transilvane de cel al multora dintre satele etnic românești dimprejur, dincolo de evidenta diferență urban/rural. Atunci când există asemănări, ele sunt o evidentă influență a ordinii urbane asupra teritoriului (așa cum se petrece, de pildă, cu arhitectura sacră de lemn), orașul, dimpotrivă, fiind practic autist la posibilele influențe ale vernacularului. Această disonanță o observa Blaga mergând și mai departe și comparând satele etnic săsești cu cele etnic românești din Ardeal. Astfel, satele săsești „și-au studiat (…) foarte mult locul unde aveau să fie clădite (…) se aliniază potrivit unor exigențe geometrice, se desprinde impresia de calcul. Satele românești sunt așezate mult mai întâmplător în peisajele ce le încadrează (…)”4. Textul lui Blaga ne sugerează că identitatea este dată în mod esențial de modul de configurare și utilizare a locului public/comunitar, de raporturile de deschidere sau de excludere reciprocă ale insulelor de spațiul privat - totdeauna însă în raport cu acest teritoriu al învecinării făcute vizibile prin prezență - care este khoros. București ieri: de-figurarea Locului public Părăsind Republica lui Platon, să ne îndreptăm către noul centru civic bucureștean. Ajunși acolo, observăm că întreg spațiul din jurul pretinsului Edificiu Public al României este înconjurat de un gard hidos, despărțind încă odată, de data asta nu doar simbolic sau ca scară, clădirea propriu-zisă de orașul în care a fost amplasată. Locul public, insula de civitate în centrul căreia problemele cetății ar fi trebuit depuse, spre a primi o rezolvare, a fost răpit și transformat într-un spațiu „privat” de factură rurală, al celui suficient de puternic spre a și-l apropria violent. Loc public păzit cu arma? Insula publică - rațiunea de a fi a centrului civic - este violată și dispare. Bucureștii sunt un oraș fără piețe, în sensul de spații publice, ale dezbaterii, ale negocierii, ale schimbului, așa cum le-a definit CNS în Habiter. Această observație tristă, pe care a mai făcut-o adeseori și prof. dr. arh. Alexandru Sandu, trebuie de îndată însoțită de o alta, pe care observația empirică o impune ca pe o evidență și studiul Danei Harhoiu a semnalat-o ca pe o caracteristică a orașului: omniprezența maidanului. Și ce este cu acele piețe civice, imitații ale forului roman - dar fără templu - construite de regimul comunist în paralel cu ofensiva reinventării județelor și, mai ales, a „municipiilor”? Sunt acestea spații publice în sensul enunțat adineauri, sunt insule ale mijlocirii împreună-locuirii? În primul rând, trebuie observat caracterul lor „utopic”, în sensul în care ele sunt construite: a) spre a înlocui centrele istoricește constituite ale respectivelor „municipii” (Ploiești, Pitești); sau b) ex-centric în raport cu acestea (Satu Mare, Tulcea, Sibiu, București). În al doilea rând, aceste „centre civice”, care se inspiră nu atât de la modelul roman, ci de la acela fascist-italian de anii treizeci (Brescia este un exemplu elocvent în această privință), nu sunt situate en meso, ci sunt, de fapt, subordonate sediului puterii, având ca punct de fugă balconul/tribună destinat aparițiilor lui Ceaușescu la „marile adunări populare”, în felul în care propunerea lui Terragni pentru Palatul Fasciilor era, în plan, o oglindă convergentă, în al cărei focar se afla tribuna liderului. Este ilustrativ în acest sens rolul impozant al tribunei de la Satu Mare (a regretatului Nicolae Porumbescu), care este detașată de restul clădirii și plutește deasupra „pieței”. În al treilea rând, derivat din afirmația anterioară, reiese caracterul de piață de defilare sau de adunări de mase, nu de reuniune a egalilor, rol pe care îl are agora, forul. Într-o schimbare dramatică, care o ilustrează pe aceea petrecută în natura puterii, edificiile politice sau administrative ale acestui secol - după experiența Palatului de Iarnă - scot în stradă nivelul piano nobile, locul public al egalilor, transformându-l într-o piață subordonată unde liderul se arată mulțimii într-un mediu complet controlat. Vom observa astfel că spațiile publice descrise mai sus nu și-au îndeplinit rolul de foruri decât o singură dată - în 1989 - când, într-adevăr, ele au fost foruri de decizie publică și colectivă. Judecând după goliciunea lor de dinainte și, mai ales, de după revoluție, se poate concluziona eșecul lor total: izolate de rutele preferate de promenadă și comerciale, ele au rămas semne ale unei puteri părăsite de solidaritatea comunităților în singurătatea piețelor civice. Întrebarea care decurge cu necesitate din cele spuse până acum este dacă, observând deficitul de spații publice, ratarea celor existente și luarea lor „în posesie” de cetățeni și chiar de insituții care, publice fiind, teoretic, ar trebui să prezerve acest caracter cel puțin pentru spațiul dimprejurul lor, trebuie să insistăm pe inventarea de spații publice în orașele românești? Ar trebui spus că există surogate pe care le luăm prea puțin în considerare mai cu seamă noi, arhitecții, fascinați de asocierea milenară dintre ideea de loc public și forma urbană de piață istoricește constituită. Or, media și rețelele de socializare, mai cu seamă Facebook, suplinesc un procent în creștere din aceste absențe sau, ca în cazul televiziunii, camuflează sau suprimă necesitatea Locului public. București: remodelarea Locului public ca fapt postmodern O modalitate de a judeca orașul și arhitectura din perspectiva postmodernă este aceea a coexistenței tuturor straturilor și intervențiilor într-un sit, chiar dacă ele vor trebui să fie coprezente într-o casă nouă. Procedeul acesta, al coprezenței, a fost foosit de Peter Eisenman în cel puțin două proiecte: cel pentru Wexner Center din Columbus, Ohio, și cel pentru intervenția în La Villete, Paris, proiectată împreună cu Derrida. În primul caz, armureria ce existase odinioară pe sit este evocată în arhitectura casei noi. În cel de-al doilea caz, toate stările anterioare ale sitului sunt prezente în același timp și coexistă - cu aceeași intensitate - cu starea „nouă”. Un exemplu este deja cunoscutul proiect pentru București 2000 al lui Von Gerkhan. De la început trebuie spus însă că, neavând niciun fel de temei economic, nu putem discuta despre acest proiect decât ca despre un agreabil exercițiu formal, dar fără niciun temei real: acesta nu a existat din nefericire - așa cum ar fi impus logica financiară - nici atunci când s-a făcut concursul și cu atât mai puțin acum. În condițiile în care, de aproape trei ani, primăria tărăgănează deschiderea activității Agenției București 2000, iar climatul investițional s-a deteriorat din cauza incompetenței și a lipsei de viziune a clasei politice și administrative, un asemenea montaj financiar este cu atât mai îndepărtat. Desigur, proiectul are și părțile lui cel puțin ciudate: Piața Unirii ar fi trebuit transformată în lac, dar, dacă judecăm că metroul de dedesubt este oricum inundat, poate că nu ar fi cea mai bună dintre variante. Un proiect pentru Catedrala Neamului (propus de regretatul Petre Ciută) a luat în serios acest aspect al proiectului lui Von Gerkhan și a izolat propusa catedrală pe un „ostrov” în centrul unui lac, ocupând o mare parte din piață și spre care ar duce doar câteva cărări subțiri. Exercițiul dlui Ciută ne atrage atenția asupra caracterului de alt tărâm al spațiului sacru. În ce-l privește pe dl Gerkhan și partenerii săi, inundarea pieței nu cred că poate fi la fel de elegant susținută și cred că nici nu poate fi imaginată o astfel de ipostază a Locului public. Block-urile (în sensul lor vestic, de unitate urbană delimitată de trei sau patru străzi) sunt placate pe un sit pe care au existat un alt sistem de străzi și o altă arhitectură; așa se face că, în carnea acestor blocuri sunt tăiate traseele vechilor străzi în chip de pasaje luminate zenital. Structura preexistentă este astfel celebrată de arhitectura nouă, prezent și precedent coexistând. Un alt exemplu interesant, proiectul câștigător, realizat de HAX srl, la concursul pentru sediul UAR, presupunea coprezența casei vechi - ruinate în revoluție, dar cu semnificație politică/simbolică - în chiar întemeierea sediului UAR, proiect câștigător al concursului organizat în acest sens de UAR (în Piața Senatului, pe ruina fostei Direcții a V-a a Securității). Într-o formă superioară, această temă a coprezenței a fost realizată de Dan Marin și de Zeno Bogdănescu în clădirea care s-a ridicat și pe care, personal, o consider cea mai provocatoare clădire construită în România după 1989 și adevăratul memorial al evenimentelor de-atunci. În ce fel pot fi prezente simultan straturile succesive de istorie ale unui sit în carnea casei noi? Această întrebare trebuie să ne-o punem cu seriozitate dacă dorim să nu fim invadați mai departe de subproducția kitsch a arhitecților neatenți nici la trăsăturile imanente ale sitului, cum ne recomandă fenomenologii, nici la istoria sa, așa cum propun deconstructiviștii. De asemenea, este o întrebare-cheie dacă dorim să conferim o identitate orașului, alta decât aceea de oraș sistematic distrus și luat de la capăt. Probabil că, în loc de a turna beton peste vestigiile vechilor hanuri bucureștene, ar trebui să medităm la ideea unor edificii introvertite, cel puțin pentru zona centrului, cu curți interioare/atriumuri pe toată înălțimea, către care să se orienteze întreaga viață a casei, chiar dacă morfologic o vom racorda pe aceasta din urmă la tipul de expresivitate vestic. Condiția esențială ar fi însă aceea ca atriumul să fie spațiu public cel puțin la nivelul străzii și, probabil, al mezaninului. Aceasta poate fi impusă drept condiție pentru oricine dorește să proiecteze în zona centrală și trebuie stipulată în tema de concurs public pentru asemenea edificii. Hanurile Bucureștilor, pe care avansul eclectismului francez le-a suprimat, pot reveni astfel la o nouă viață, sub forma galeriilor comerciale acoperite, a pasajelor străbătând centrul istoric revitalizat, a atriumurilor la clădirile individuale și a curților în profunzimea edificiilor, de felul celor pe care le găsim la clădirile interbelice de pe Calea Victoriei. Aici există aceste spații semiprivate, salvate din vânzoleala străzii, prin care treci cu necesitate mai înainte de a intra în holul clădirii propriu-zise. La Regia Monopolurilor lui Duiliu Marcu, acesta elogia în cartea sa de proiecte din 1940 exact o atare curte interioară pentru uzul amploiaților. În centrul Bucureștilor există o suită de clădiri „gemene”, flancând intrarea într-o curte interioară a ansamblului respectiv; indiferent dacă expresia lor este neo-românească, neo-maură sau modernistă, aceste ansambluri articulate în jurul unui spațiu semiprivat împărtășesc o aceeași perspectivă asupra relației public-privat care nu trebuie privită în termeni de excludere mutuală, ci, dimpotrivă, în sensul unei parcurgeri graduale, mai puțin traumatizante. Probabil că această înțelepciune nu ar trebui pierdută, cu tot aerul oriental al tipologiei (sau, dacă ne amintim de cvartale, împotriva asocierii lor cu stalinismul). În acest sens, trebuie examinată capacitatea block-ului vestic (unitate urbanistică formată din construcții dispuse în jurul unei curți, pe perimetrul delimitat de patru străzi) de a propune un tip similar de spațiu semipublic înlăuntrul său. Proiectul lui Meinhard von Gerkhan pentru „noul centru civic”, rezultat în urma concursului internațional București 2000 (1995-’96), instituie asemenea block-uri - prea puțin folosite până acum în textura urbană a Bucureștilor - în zona din jurul Casei Republicii. Este evident că, dată fiind natura locului unde ar fi să fie amplasate, este extrem de improbabil că intimitatea unor spații de locuit poate fi asigurată în același fel în care aceasta s-ar putea instala într-un amplasament „neutru” din punct de vedere al vieții publice. Subsolurile cu bolți din centru pot fi regăsite ca tipologie și folosite pentru restaurante, baruri, cluburi. Materialele naturale - piatră, lemn - pot intra în dialoguri și contraste fertile cu cele high-tech (metal și sticlă), așa cum se întâmplă, de altfel, în operele marilor arhitecți (Aalto, Siza, Wright, Ando, H. Fathi, Herzog&De Meuron etc.) Sticla, atât de prezentă în arhitectura contemporană, poate fi folosită și în modul propus de orașul de târgoveți - geamlâcul - cu o expresie adusă la zi. Așa o dorea Constantin Joja și așa a fost ea folosită în cazul sediului BCR Sector 6, din Bd. Ghencea (arh. Dorin Ștefan, DS Studio). Înnoirea nu trebuie să însemne preluarea mimetică a tipologiilor și a tehnologiilor, de regulă, epuizate expresiv în Vest. Nu trebuie cu necesitate să repetăm erorile arhitecturii modernismului ortodox, cum îl numea Robert Venturi (nicio legătură cu religia eponimă), ci putem găsi întemeieri pentru o arhitectură proprie capitalei, în care actualitatea să fie ecoul ipostazelor trecute ale locului, iar acesta din urmă să piloteze din infratext actul de proiectare. Metodele noi de investigare a arhitecturii și urbanismului oferă această deschi-dere alternativă către șansa de a fi contemporani fără a alunga în proces trăsăturile - multe, puține, câte sunt - care particulari- zează acest oraș. Închei scurtele mele notații despre spațiile-insulă ale locuirii laolaltă cu remarca - desprinsă dintr-un comentariu mai larg al arhitectului și filosofului arhitecturii poststructuraliste care este Rem Koolhas - potrivit căruia ideea de Loc public și, mai ales, obsesia privind necesitatea prezenței sale în oraș sunt două dintre marotele arhitecților care, încet, încet, încetează să mai aibă importanța din teoriile urbanistice ale deceniilor trecute5. Desigur, situația șade complet diferit în cazul specific al României, unde deprinderea dialogului (inter)comunitar trebuie să fie dublată de apariția expresiei acestor spații civice - de la transparența și fortificarea atributelor publice ale instituțiilor la piețe și de la televiziune și media la Facebook. Dar concluzia pe care o sugerez este aceea că orice discuție despre Loc public trebuie să se desfășoare numai după ce există în comunitate o masă critică de spațiu privat, de locuințe unifamiliale de felul cartierelor construite după criteriul „breslei” până după război. Locul public depinde de existența spațiului în întregime privat, în care se întemeiază ființa și din ocrotirea căruia, ca să parafrazez o spusă heideggeriană, omul, locuind, poate înfrunta și alte tipuri de spații. |

| 1.

Desigur, poate exista și spațiu public ca ricoșeu al spațiului privat (Sp), în sensul în care privit și privitor sunt conținuți ca parte a aceluiași spațiu: este cazul unei săli a tronului din interiorul cutărui palat regal sau, dimpotrivă, al unui panoptikon. Cu toate acestea, spațiul public va fi folosit aici cu precădere în înțelesul său social, fără a avea cu necesitate atașat o configurație în cadrele spațiului fizic.

2. „Architecture is the arrangement of space for excitement”, Philip Johnson în „What I’ve Learned”. 3. „Gardianul sensului nu are nevoie să se alimenteze din eveniment decât pentru a-l cita să compară în procesul pe care doctrina îl intentează realului. Nu trebuie să se întâmple decât ceea ce este anunțat să se întâmple” (Lyotard, 1997, 83). 4. Textul prezintă un interes cu totul special pentru cercetătorii problemei identității, pentru că, spre deosebire de conceptul de matrice stilistică, pare să accepte că identitatea este totdeauna o problemă de diferențe specifice în interiorul unui context, care trebuie așadar comparate, iar nu un dat imanent, impermeabil la context, al unei etnii; în cazul în speță, anumite trăsături ale modului de organizare a satelor românești pot fi prezentate doar prin comparație cu satele săsești împreună cu care împart o aceeași geografie și o aceeași climă. 5. De altfel, nici „piețele civice” nu sunt o idee complet nouă a regimului comunist român; anii cincizeci și șaizeci sunt plini de asemenea experimente „civice” în Occident, mai cu seamă în orașele germane și chiar în SUA. Am comentat pe larg aceste „tendințe elefantine” (William J. R. Curtis) în studiul dedicat problemei și inclus în New Europe College Yearbook 1995-’96, București, Humanitas, 1999. |

| The public place comes into existence as soon as some person other than myself enters a given territory and it becomes possible for me not only to look around me, but also for me to be looked at. The spatialisation of the event of seeing and being seen is the elementary level of the public place. |

| Such a place, once employed for the purpose shown above, must then fold itself back into vagueness, into the pre-formed state of space. This place will exist for only as long as the event that invents the space it requires exists, the aura in which it will take place, in the way in which objects, too, invent their own space.

The event is here to be understood as a system of dynamic relations, in which the essential role is played by visibility, which is established at a given moment (and for a determinate period) between at least two human beings. The event “takes place”, and thus it extracts, unfolds the space of its occurrence - the public space. Public place > public space The reason why this text chiefly makes use of the term public place derives from the way in which this has been defined above: the attribute of being public necessarily presupposes as a spatial “stage” only an expanse, rather than a space that is de-limited (via various means of construction, but also through the choice of a closed off natural space)1. The word place here points to the fact that there exists only a minimal spatial requirement for the coming into being, for the occurrence of a public event, a limited surface area. The limits of the place are provided by the breadth of the event itself, in its unfolding, rather than by prior acts of building; it is the event extracts that portion of space from spatium rather than the building of it; the latter, on the condition that it should remain minimal and low level (precisely in order not to impede reciprocal visibility), can come as a consequence, as an ascertainment of the recurrence of a certain event within a given localisation, rather than a precondition capable of “invoking”, of “lubricating” the emergence of the event. In the public place it is possible for events to take place simultaneously, to coexist within the same territory, events such as the negotiations that this exchange of visibility makes possible (trade, shared decision-making2) or confrontations (the battlefield, the space of punishment). These are actions that take place “openly, in the light of day, as opposed to secret procedures” (Vernant, 1995: 70). Authoritarian regimes, whose relationship with place and public places will be discussed later, have a tendency to exert integral control3 over this unfolding in the open of the event or, as Lyotard puts it, “to keep the event under the authority (of totalitarian bureaucracy)” - (Lyotard, 1997: 83). It is sufficient, however, to glimpse the virtual character of a natural place and that there be a small amount of arrangement in order for it to be illuminated through the act of the event, through visibility. In other words, in order for a place to become a public place, a “forest clearing” is sufficient; there is not necessarily any need for Raum. The Raum can subsequently become built space, although when nomads temporarily take possession of it to build their camp all that is required is cursory clearance and arrangement. Some anthropologists, such as Angelo Moretta, and even archaeologists, such as François de Polignac, go so far as to explain the appearance of settlements through the grouping around a site “illumined” by typically sacred events, “la cité cultuelle” (as de Polignac calls it), through fortification, inner geometry, building within limits. It is therefore a domain of dwelling, which, precisely because of its quality of taking place in the vicinity of the other, somehow guarantees the frequency of encounters which themselves barely manage to guarantee self-perpetuation as an event of the original “forest clearing”, Q.E.D. public place. The conclusion of this minimal arrangement required by the place in which the public event is about to occur will obviously be disappointing for architects, who have long believed that the recipe for the public space is geometrically quantifiable and that it depends upon the rigour with which they will have designed “civic” spaces: monuments, edifices, heroism set in stone. But on the contrary, it is often observed that the recipe for the public space is more evanescent than they thought and that it eluded, for example, the Romanian architects of the 70s, 80s and 90s, who built “civic centres” in each county administrative seat according to the vulgarised (and, significantly, laicised) formulas of the Roman forum, in the process sacrificing the real centres of the towns in question (which were turned into municipalities). Perhaps there is a non-built Public Place, which the gaze can scan at will, such as the dance ring (the place where the Sunday ring dance took place in the Romanian village, for example), the battlefield, or, more commonly, the public marketplace. Habermas emphasises the fact that “the public life, bios politikos, unfolds in the marketplace, the agora, but without it being bound in any way to this particular place. The public sphere is constructed within the framework of speech (lexis), which likewise can take the form of a debate or a trial, as well as a joint action (praxis), such as the waging of war or war games” (1998, 47). In Conversations with Students (1996), Rem Koolhaas severely criticised this demiurgic obsession with the fixed, built and wholly controlled civic spaces that architects wish to establish in cities. Although he does not formulate it as such, Koolhaas’ conclusion seems to be that the attribute of being a public space does not presuppose a prior built intervention and, contrariwise, the mere fact that a certain space has been fitted out and titled “civic”, “public” or “meeting place” does not necessarily mean that it will be used as such by the members of a community. The public place brings collective identity to awareness The identity of a (collective, local, regional, ethnic) group is eloquently expressed by the way in which the Public Space is made visible, administered and utilised and, above all, by the relationship between Public Space and Private Space. This mode is a function of time, rather than being given and unchangeable, and therefore it has a processual character and likewise a particular history of its own becoming. Changes in land ownership have just as much influence on identity in relation to the use of the common space as cultural or psychological shifts, or socio-political changes (for example, whether the emphasis is on the individual or the collective). Identity, as it presents itself when it inserts itself into space and, above all, when it embeds the relationship within a building, becomes enlightening only when it is expressed not in absolute terms, but in degrees of comparison. Identity is an attribute of the local, of vicinity, and it is a matter of degree, rather than a difference of rank. Christian Norberg Schulz accepts the differences of character (including the degrees of ordering) that can exist between an object, architecture, and the place to which it belongs, or between place, locality and overall area, in terms of topology. If we are talking about the rural architecture of a territory inhabited by different ethnic groups (Transylvania and Dobrudja are two enlightening examples in this respect), we shall be able to establish local, molecular differences as soon as the climatic and relief factors have been simplified; what is left over is therefore cultural differen-ce. It is only in such “units of vicinity”, in comparable islands of proximity, that it is possible to carry on a relevant discussion about the identity expressed through architecture. Other types of distant comparison, for example between the vernacular architecture of some Romanian regions and the islands of Japan - a practice specific to the 70s and 80s in Romania, when it seemed that the Japanese example of unbroken evolution from tradition to modernity could be reconciled with Romanian national-communist rhetoric - become completely irrelevant and are probably due more to similarities of climate, relief, and geographic isolation. An approach within the local and regional framework, from the perspective of the various aspects of management of a similar geography, is therefore the path to be followed in the discussion about identity. Identity is established through processes of assimilation and rejection of competing models from the same territory or neighbouring territories. An eloquent example of this comparativist molecular vision of identity is paradoxically provided by Lucian Blaga, but not in his concept of the “matrix”. Rather, it is to be found in an article marginal to his main work, published in Cuvântul 2 (274)/4 October 1925. Blaga’s text suggests that identity is essentially given by the mode in which the Public Space is configured and utilised, and by the islands of the Private Space’s relationships of reciprocal openness or exclusion - albeit always in relation to the Public Space, that territory of vicinity that has been made visible. We know how different is the character of the Saxon towns of Transylvania from that of many of the ethnic Romanian villages around them, quite apart from the obvious difference between urban and rural. When there are similarities, they obviously arise from the influence of the urban order on the territory (this is what happens, for example, with wooden ecclesiastical architecture), with the city remaining impervious to any potential influence from the vernacular. Blaga observes this dissonance even further when he compares ethnic Saxon with ethnic Romanian villages in Transylvania. Thus, the Saxon villages “have studied (…) deeply the place where they were to be built (…) they are aligned according to geometric exigencies, they give the impression of calculation. Romanian villages are situated more randomly in the landscapes that surround them.”4 Blaga’s text suggests that identity is essentially given by the mode in which the public/communal place is configured and utilised, by the relationships of reciprocal openness or exclusion existing among the islands of private space, but always in relation to the territory of vicinity made visible through presence that is the khoros. The Bucharest of yesterday: the disfigurement of the Public Space Let us leave behind Plato’s Republic and head towards Bucharest’s new civic centre. Having arrived there, we observe that the entire space around the supposed Public Edifice of Romania is surrounded by a hideous fence, which separates yet again, not merely symbolically or in terms of scale, the building proper from the city in which it is situated. The public space, the civic island at whose centre the problems of the city ought to have been submitted for resolution, has been snatched away and transformed into a rural-style “private” space, a space that belongs to whomever is strong enough to seize it violently. A public place guarded by guns? The public island - the raison d’être of the civic centre - is violated and disappears. Bucharest is not a city with plazas, in the sense of public spaces for debate, negotiation and exchange, as the CNS defines them in Habiter. This sad observation, which has also often been made by Professor Alexandru Sandu, must straightaway be joined with another, one that is empirically obvious and which Dana Harhoiu’s study has pointed to as being characteristic of the city: the omnipresence of the maidan (vacant lot, patch of waste ground). What is with these civic plazas, imitations of the Roman forum, albeit without a temple, built by the communist regime in parallel with the onslaught of the reinvention of the counties and, above all, the “municipalities”? Are they public spaces in the sense given above? Are they islands to mediate co-habitation? What must first be noted is their “utopian” character, in the sense that they are constructed: a) as a replacement for the built historic centres of the “municipalities” in question (Ploiești, Pitești); or b) ex-centrically in relation to these centres (Satu Mare, Tulcea, Sibiu, Bucharest). In the second place, these “civic centres”, which are inspired not so much by the Roman model as much as by the Italian fascist model of the 1930s (Brescia being a good example), are not situated en meso, but are in fact subordinated to the seat of power, and have as their vanishing point the balcony/podium intended for Ceaușescu’s appearances at “grand people’s assemblies”, in the same way as Terragni’s proposal for the Palace of the Fasces took the plan of a converging mirror at whose focus was placed the leader’s podium. Illustrative in this respect is the imposing role of the podium in Satu Mare (designed by the late Nicolae Porumbescu), which is detached from the rest of the building and floats above the “plaza”. In the third place, following on from the foregoing statement, such plazas are essentially designed for parades and mass gatherings, rather than for meetings of equals, which was the role of the agora or forum. In a dramatic shift, which illustrates that which has taken place in the nature of power, the political and administrative edifices of that century - after the experience of the Winter Palace - evict the piano nobile level, the public place of equals, onto the street, transforming it into a subordinated plaza where the leader shows himself to the crowd within a completely controlled environment. We may note that the public spaces described above fulfilled their role as forums only once, in 1989, when they genuinely became forums for public and collective decision. Judging by their emptiness before and, above all, after the Revolution, we may conclude that they have been a total failure: isolated from preferred routes for walking and shopping, they have remained as signs of a power abandoned by the solidarity of the community to the solitude of the civic plazas. The question that necessarily arises from what has been said up to this point is whether, having observed the deficit of public spaces, the failure of those that exist, and their taking “into possession” by private citizens and even institutions which, being public at least in theory, ought to preserve their public character at least in the surrounding space, we ought to insist upon inventing public spaces in Romanian cities. It should be said that there are surrogates to which we architects in particular pay too little attention, fascinated as we are by the millennial association between the idea of the public place and the historically established urban form of the plaza. The media and social networks, Facebook in particular, are increasingly compensating for such absences or, as in the case of television, camouflaging or suppressing the need for the Public Space. Bucharest: reshaping the Public Space as a postmodern fact One way of judging the city and architecture from the postmodern perspective is in terms of the coexistence of all the strata and interventions within a site, even if they will have to be co-present in a new building. The procedure of co-presence has been used by Peter Eisenman in at least two projects: the Wexner Centre in Columbus, Ohio, and the La Villete intervention in Paris, designed together with Jacques Derrida. In the first case, the armoury that formerly existed on the site is evoked in the architecture of the new building. In the second case, all the previous states of the site are presented simultaneously and coexist with the “new” state just as intensely. One example is Von Gerkhan’s by now famous project for Bucharest 2000. From the outset it should be said that in the absence of any economic basis, we can only discuss this project as a pleasing formal exercise, without any real foundation: unfortunately, it did not exist - as financial logic would have demanded - even when the competition took place, and exists even less so now. In the situation in which for almost three years the city hall has been dragging its feet when it comes to getting the Bucharest 2000 Agency up and running, and the investment climate has deteriorated due to incompetence and lack of vision on the part of the political and administrative class, such a financial montage is further away than ever. Of course, the project also has its rather strange aspects: Unirii Plaza would have been turned into a lake, but if we take into account that the metro beneath it is flooded anyway, perhaps this would have been one of the best options. A design for the Cathedral of the Nation (proposed by the late Petre Ciută) took this aspect of von Gerkhan’s project seriously and isolated the proposed cathedral on an islet in the middle of the lake, occupying a large part of the square and with access along just two narrow walkways. Ciută’s exercise draws our attention to the otherworldliness of the sacred space. As far as Gerkhan and his partners are concerned, I don’t think the flooding of the plaza would have been as elegantly achieved and nor can the Public Space be imagined in such an embodiment. The blocks (in the western sense of an urban unit delimited by three or four streets) are superimposed upon a site where a different street grid and architectural system existed. This is why the flesh of these blocks is incised by the courses of the old streets in the form of passageways illumined from overhead. The pre-existing structure is thus celebrated by the new architecture, with the present and the precedent coexisting. Another interesting example, the winning project for the Union of Romanian Architects headquarters, designed by HAX S.R.L., presupposes the co-presence of the old building - partly destroyed during the Revolution, but with a political/symbolic significance: the ruin of the former Department 5 of the Securitate. In a higher form, the theme of co-presence has been achieved in Dan Marin and Zeno Bogdănescu’s building, which I personally regard as one of the most provocative to have been constructed in Romania since 1989, a true memorial to the events of the Revolution. How can the succeeding strata of a site’s history be presented simultaneously in the flesh of a new building? This is a question we seriously need to ask ourselves if we want to put a stop to the invasion of kitsch sub-production by architects unconcerned with the immanent features of a site, as the phenomenologists recommend, or its history, as the deconstructionists propose. Likewise, a key question is whether we wish to confer an identity upon the city, other than the identity of a city systematically destroyed and built all over again. Instead of pouring concrete over the remains of Bucharest’s old inns, we probably ought to meditate on the idea of introverted buildings, at least in the city centre, buildings with inner courtyards/atriums, towards which the whole life of the building is oriented, even if morphologically we will couple this with western-type expression. The essential condition, however, is that such an atrium would be a public space, at least at street level and probably also at the level of the mezzanine. This could be laid down as a condition for anyone who wishes to design buildings in the city centre and should be stipulated in the theme of the public competitions for such buildings. The inns of Bucharest, which the advance of French eclecticism stifled, might thereby gain a new lease of life, in the form of covered shopping galleries, of passageways crisscrossing a revitalised historic centre, of atriums in individual buildings and deep courtyards, of the kind which we find in the inter-war buildings on Calea Victoriei. Here can be found those semi-private spaces sheltered from the bustle of the street, through which you must pass before entering the lobby of the building proper. In his design proposals for the Monopolies Department building, architect Duiliu Marcu praised precisely such an inner courtyard for the use of employees. In central Bucharest there is a series of “twin” buildings, flanking the entrance to inner courtyards. Regardless of whether they are Neo-Romanian, Neo-Moorish, or modernist in design, these ensembles articulated around a semi-private space share the same perspective on the relationship between public and private, which should not be viewed in mutually exclusive terms, but rather in the sense of a gradual, less traumatic transition. Such wisdom probably ought not to be lost, despite the oriental air of the typology (or, if we recall the kvartaly, despite their association with Stalinism). In this respect, we need to examine the capacity of the western block (an urban unit made up of buildings arranged around a courtyard and delimited by four streets) to put forward a similar type of semi-public space within itself. Meinhard von Gerkhan’s design for the “new civic centre”, the result of the international Bucharest 2000 competition (1995-’96), establishes such blocks - hitherto underused in the urban fabric of Bucharest - around the House of the Republic. It is obvious that, given the nature of the place where they would have been situated, it would have been extremely unlikely that the privacy of the dwelling spaces would have been guaranteed in the same way as on a site “neutral” from the point of view of public life. The vaulted cellars of central Bucharest can be rediscovered as a typology and used for restaurants, bars and clubs. Natural materials (stone, wood) can enter into a dialogue and create fertile contrasts with high-tech materials (metal, glass), as is the case in works by major architects such as Aalto, Siza, Wright, Ando, H. Fathi, Herzog and De Meuron. Glass, which is so common in contemporary architecture, can also be used in the way proposed by the Bucharest of merchant times, in the form of an updated geamlâc (corridor or veranda closed off by a wall consisting of small panes of glass joined together in a grid). This was what Constantin Joja proposed and it has been put to use in the branch of the Romanian Commercial Bank on Ghencea Boulevard (architect Dorin Ștefan, DS Studio). Innovation does not have to mean the mimetic adoption of typologies and technologies that have exhausted their potential for expression in the West. We do not necessarily have to repeat the errors of orthodox modernist architecture, as Robert Venturi called it, but rather we can discover the foundations for an architecture specific to our capital, in which the contemporary would find its echo in the past embodiments of the place, and the place would guide the act of design from the infra-text. The new methods of investigating architecture and urbanism provide this alternative opening towards the opportunity to be contemporary without banishing in the process the features that particularise the city, however few or many of these there might be. I shall conclude my brief notes on the island-spaces of dwelling together with the observation - taken from a more extensive commentary by architect and philosopher of postmodern architecture Rem Koolhaas - that the idea of the Public Space and, above all, the obsession with the need for its presence in the city are two of the totems of architects who are gradually ceasing to be of importance in the urbanist theories of recent decades5. Of course, the situation is completely different in the specific case of Romania, where the knack of (inter-)community dialogue ought to be fostered and to combine with the emergence of the expression of these civic spaces - from the transparency and reinforcement of the public attributes of institutions to plazas, and from television and the media to Facebook. But the conclusion I suggest is that any discussion about the Public Space ought to unfold only after a critical mass of private space, of one-family homes of the type found in the districts built according to “guild” criteria up until the Second World War, exists in the community. The Public Space depends on the existence of the wholly private space, in which being is rooted and from whose sheltering protection, to paraphrase Heigegger, man may, by dwelling, confront other types of spaces. |

| 1.

Of course, the public space can also exist as a ricochet of the private space, in the sense in which the viewed and the viewer are contained as a part of this space: this is the case of a throne room within a royal palace or the case of a panoptikon. Nevertheless, the term public space will be used here mainly in its social sense, without necessarily being attached to a configuration within the physical space.

2. “Architecture is the arrangement of space for excitement”, Philip Johnson in “What I’ve Learned”. 3. “The guardian of the meaning does not need to be nurtured by the event except to quote it in order to compare it in the trial that the doctrine brings against the real. Only what has been announced will happen, must happen” (Lyotard, 1997, 83). 4. The text is of particular interest to researchers into the problem of identity, because in contrast to the concept of the stylistic matrix it seems to accept that identity is always a matter of specific differences within a context, which therefore need to be compared, rather than an immanent given, impervious to context, of an ethnic group; in this particular case, certain features of the way in which Romanian villages are organised can be presented only via comparison with the Saxon villages with which they share the same geography and climate. 5. In any case, not even the “civic plazas” are a wholly new idea of the Romanian communist regime; in the West in the 1950s and 60s there were numerous such “civic” experiments, particularly in West Germany, but also even in the USA. I have written about these “elephantine tendencies” (William J. R. Curtis) at greater length in a study included in the New Europe College Yearbook, 1995-’96 (Bucharest, Humanitas, 1999). |