Ambiguitatea holistică a apropierii de peisaj

The Ambiguous Holistic attitude of Landscape

| Atunci când l-am auzit prima dată pe Richard Weller menționând cuvântul „holistic” în context peisagistic am fost atras pe loc de felul în care suna acest cuvânt. Cred cu tărie în sunetele cuvintelor, în capacitatea lor de a evoca noi percepții ale mediului înconjurător. Pe măsură ce vizualizam sunetul cuvântului „holistic” mi-a venit în minte un poem de Baudelaire. |

| „Natura e un templu ai cărui stâlpi trăiescȘi scot adesea tulburi cuvinte,

ca-ntr-o ceață; Prin codri de simboluri petrece omu-n viață Și toate-l cercetează cu-n ochi prietenesc. Ca niște lungi ecouri unite-n depărtare Într-un acord în care mari taine se ascund, Ca noaptea sau lumina, adânc, fără hotare, Parfum, culoare, sunet se-ngână și-și răspund. Sunt proaspete parfumuri ca trupuri de copii, Dulci ca un ton de flaut, verzi ca niște câmpii, Iar altele bogate, trufașe, prihănite, Purtând în ele avânturi de lucruri infinite, Ca moscul, ambra, smirna, tămâia care cântă Tot ce vrăjește mintea și simțurile-ncântă.”1 |

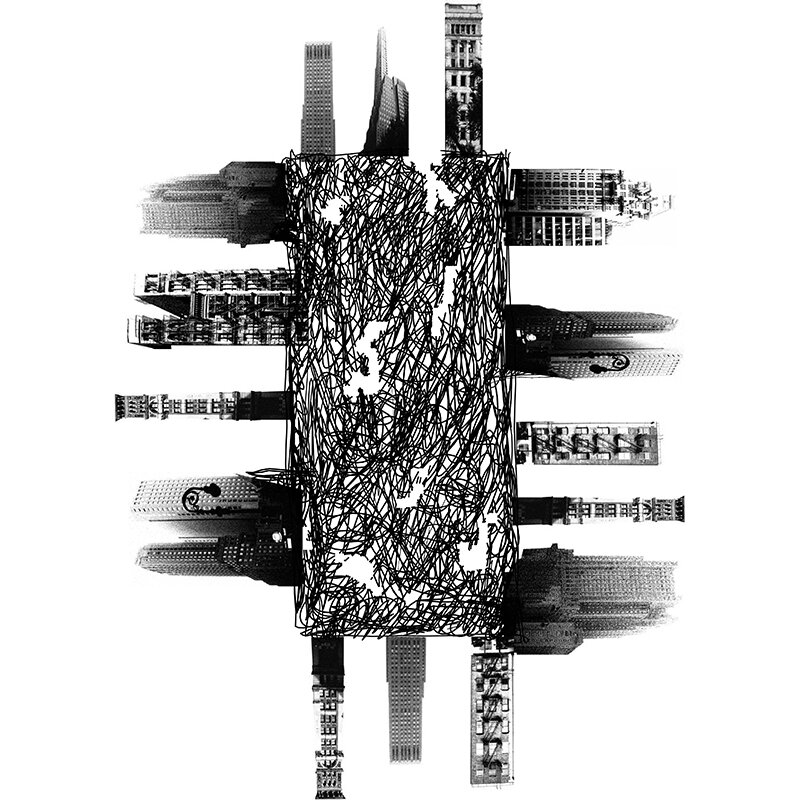

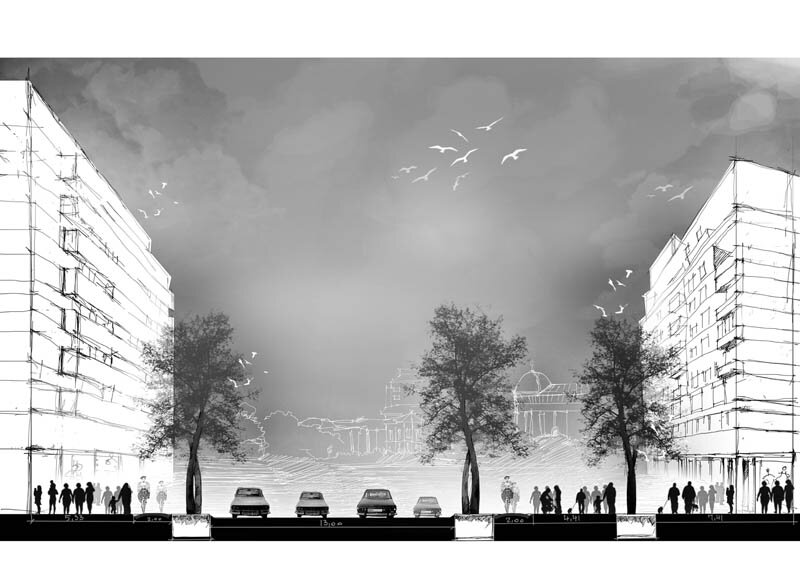

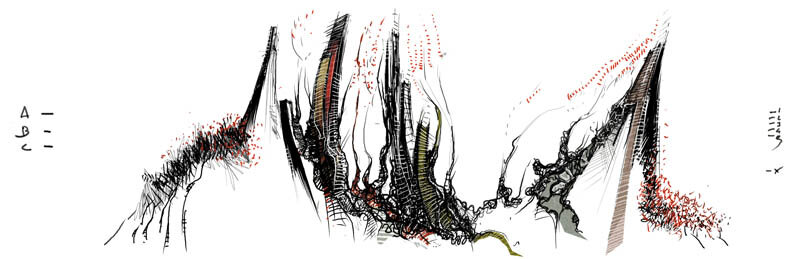

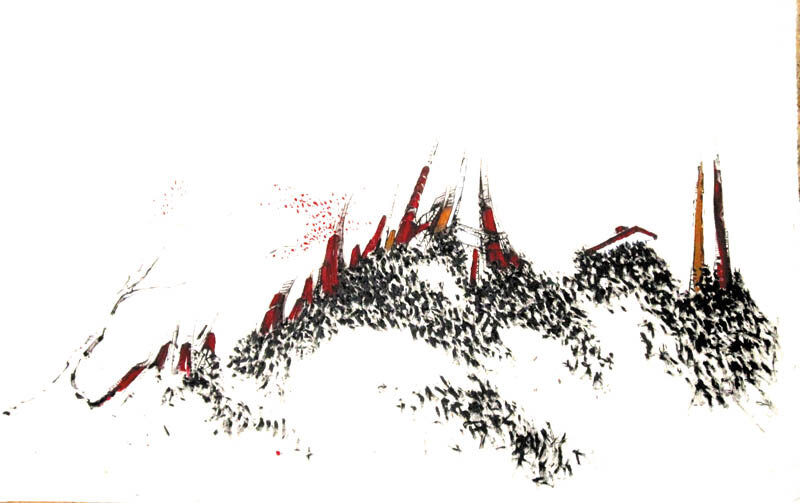

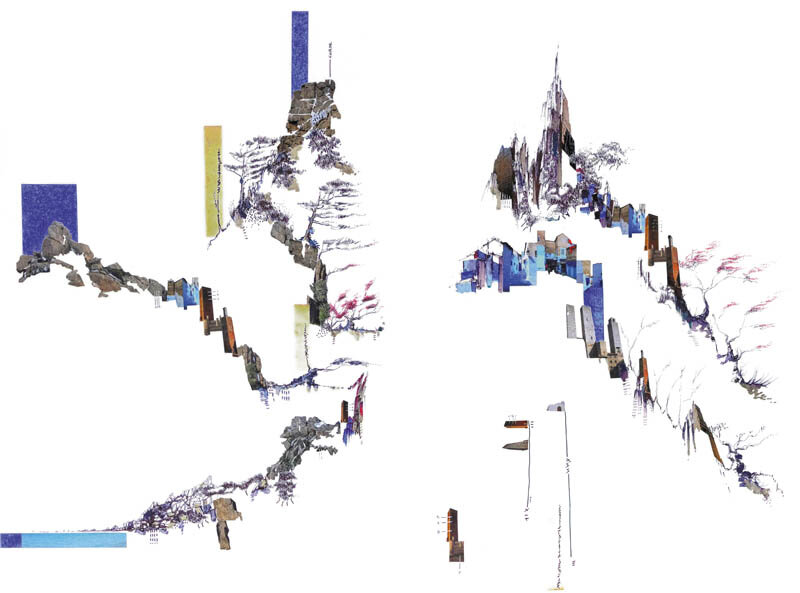

| Sensul cuvântului englez „holistic” este același cu cel al cuvântului italian „Olistico”; ar putea părea că mă bazez pe un concept evident, însă știm cu toții că nu este adevărat. În limba engleză explicația este: „care are legătură cu sau se referă la entități întregi sau la sisteme complete mai degrabă decât la analiza, tratarea sau disecarea în părți componente. Medicina holistică încearcă să trateze atât mintea, cât și trupul; ecologia holistică prive- ște oamenii și mediul acestora ca pe un singur sistem unitar” (Merriam-Webster). Holistic vine din holism, cuvânt de origine greacă, și înseamnă întreg, tot, integral: „teorie potrivit căreia universul și, în special, natura vie sunt văzute în mod corect ca întreguri ce interacționează, ca organisme vii, ce sunt mai mult decât simpla sumă a particulelor elementare”.În opinia mea, cuvântul „holistic” este oarecum ambiguu; el identifică o entitate complexă ce rezultă din suma tuturor elementelor sale care sunt însă diferite de ceea ce putem eticheta drept „identitate”. Nu este clar definit geometric sau spațial, dar, în același timp, generează o margine densă în jurul tuturor elementelor „identității”, unde înțelesurile ambigue sunt suficient de elastice pentru a se mișca din interior spre exterior sau viceversa: John Dixon Hunt o denumește poezie, iar Richard Weller o consideră o atitudine ecologică în arhitectura peisagistică contemporană.

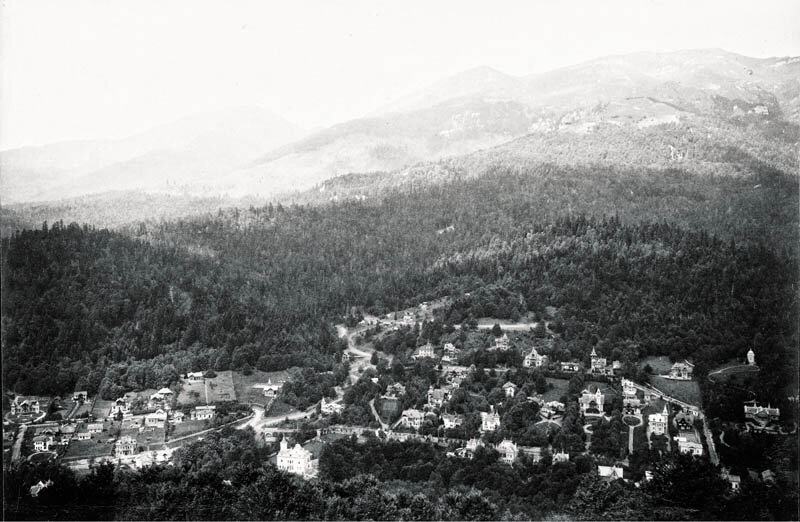

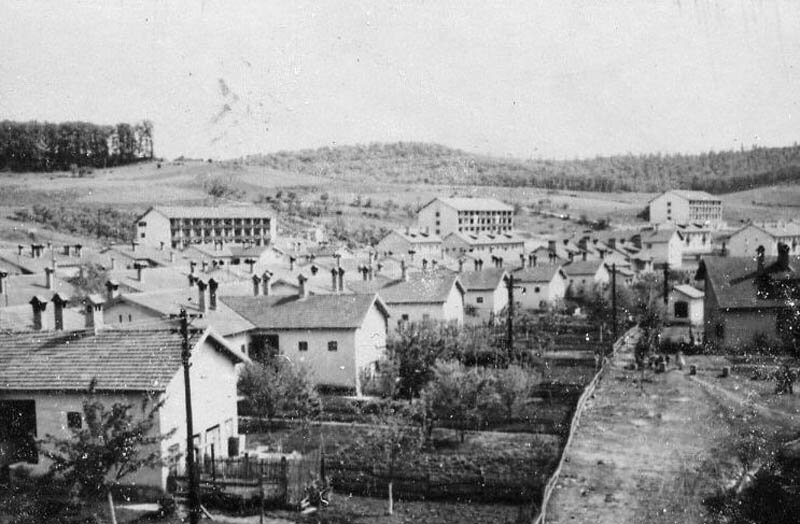

În urmă cu mulți ani am citit un scurt poem de Ungaretti, important poet italian care a trăit la începutul secolului al XX-lea. Se referea la covoarele persane și la modul în care sunt percepute culorile și compoziția acestora. Poetul spunea astfel: „calore dei tappeti Persiani, ogni colore si adagia e si espande nei colori vicini, per essere piu` solo se lo guardi”. Versiunea mea în limba engleză ar fi: „Warm of the Persian Rugs, each color lies and expands on the near colors, to be much more than if you look it alone”. („Căldură a covoarelor persane; fiecare culoare există și se extinde către culorile apropiate, pentru a fi mai mult decât este atunci când o privești doar pe ea”.) Astfel, putem vedea si noi peisajul. La începutul cărții sale „Sense of Time Sense of Space”, John B. Jackson scrie că a fost unul dintre primii oameni care au privit natura de sus, de unde a recunoscut nesfârșitele terenuri agricole americane împărțite în parcele și idealismul democratic care se afla cândva în spatele lor. În alte cărți a scris despre scara peisajului vernacular american, demonstrând o capacitate incredibilă de a schimba scara propriului concept, păstrând, în același timp, o viziune holistică asupra realității, într-un fel, aceeași viziune pe care au avut-o și Jackson Pollok și Mark Rothko în picturile lor abstracte: impregnată de o tentă oarecum politică și instituțională în straturile geometrice infinite ale lui Rothko, mai complicată, complexă, confuză și precisă în spațiul vernacular al lui Pollok. |

| Citiți textul integral în numărul 5/2013 al revistei Arhitectura |

| 1 Traducere de Alexandru Philippide (nota traducătorului). |

| When, for the first time, I listened to Richard Weller mentioning the word “holistic” in the field of Landscape, I immediately perceive its sound as something attractive. I believe in the sound of words to evocative new perceptions of the environment. As I visualize the sound of “holistic”, a poem from Baudelaire comes to my mind. |

| “Nature is a temple in whichliving pillars

Sometimes give voice to confused words; Man passes there through forests of symbols Which look at him with understanding eyes. Like prolonged echoes mingling in the distance In a deep and tenebrous unity, Vast as the dark of night and as the light of day, Perfumes, sounds, and colors correspond. There are perfumes as cool as the flesh of children, Sweet as oboes, green as meadows - And others are corrupt, and rich, triumphant, With power to expand into infinity, Like amber and incense, musk, benzoin, That sing the ecstasy of the soul and senses.” |

| The meaning of the word “Holistic” in English and Italian “Olistico” is the same; it seems I am relying on an obvious concept, but all of us know it is not true. The English explanation is: “relating to or concerned with wholes or with complete systems rather than with the analysis of, treatment of, or dissection into parts - holistic medicine attempts to treat both the mind and the body - holistic ecology views humans and the environment as a single system” (Merriam-Webster). Holistic comes from Holism a word with Greek origins and meanings such as whole, all, entire: “a theory that the universe and especially living nature is correctly seen in terms of interacting wholes - as of living organisms - that are more than the mere sum of elementary particles”.I believe that the word “holistic” is somewhat ambiguous; it identifies a complex entity emerging from the sum of all its elements that are then different from what we can identify as “identity”. Nothing with precise geometry or space but, in the same time, it generates a dense margin all around the elements of the “identity”, where ambiguous meanings have a resilient capacity to deal from inside to outside or vice versa: John Dixon Hunt calls it poetry, and Richard Weller refers to it as an ecological attitude in contemporary landscape architecture.

Many years ago I read a short poem from Ungaretti, an important Italian poet who lived in the early 20th century. It was about Persian Rugs and how he perceived the colors and their composition. He wrote: «calore dei tappeti Persiani, ogni colore si adagia e si espande nei colori vicini, per essere piu` solo se lo guardi». My English version is: “Warm of the Persian Rugs, each color lies and expands on the near colors, to be much more than if you look it alone”. This is how we can see the landscape. John B. Jackson, at the beginning of the book “Sense of Time Sense of Space”, writes that he was one of the first who looked at the landscape from above, recognizing the endless grids of American agriculture and the democratic idealism that once underpinned it. In other books, he wrote about the scale of vernacular American Landscape, using the incredible capacity to change the scale of his concept but still having a holistic vision of the reality; in a way the same visions that Jackson Pollok and Mark Rothko had in their abstract paintings. Many more political and institutional in the infinitive geometrical layers for Rothko, much more intricate, complex, confused and precise in the vernacular space of Pollok. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |