Vecinătatea lui Dürer

Dürer’s Vicinity

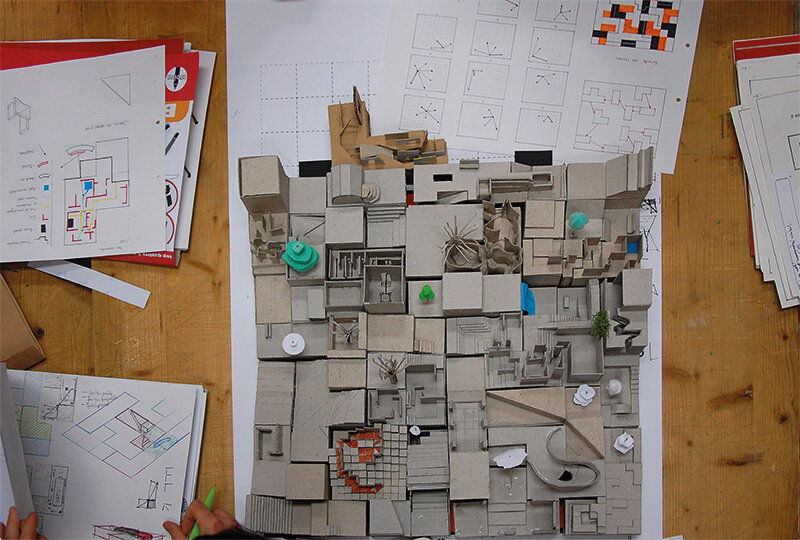

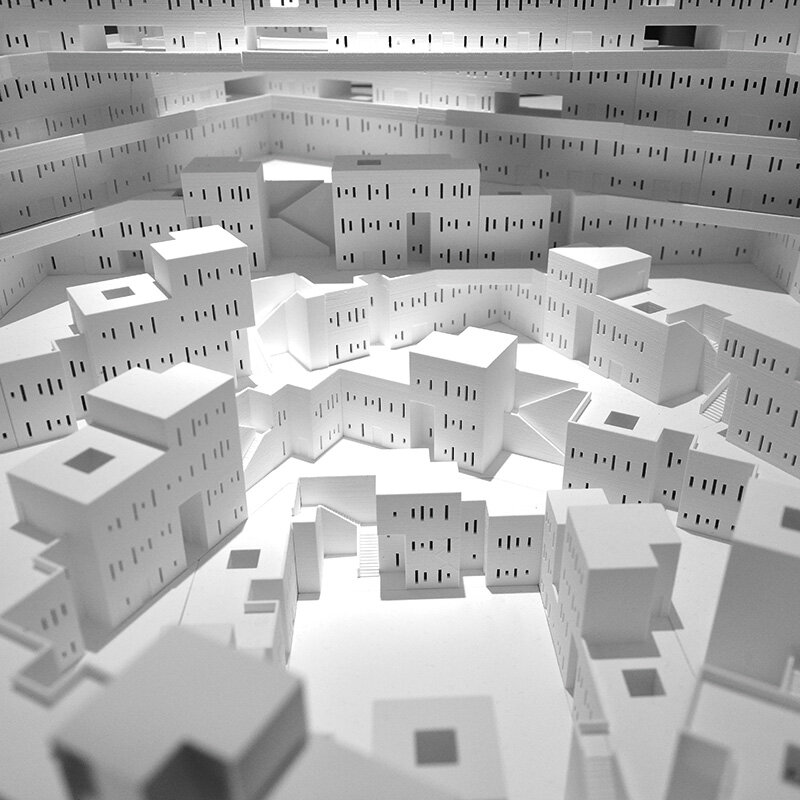

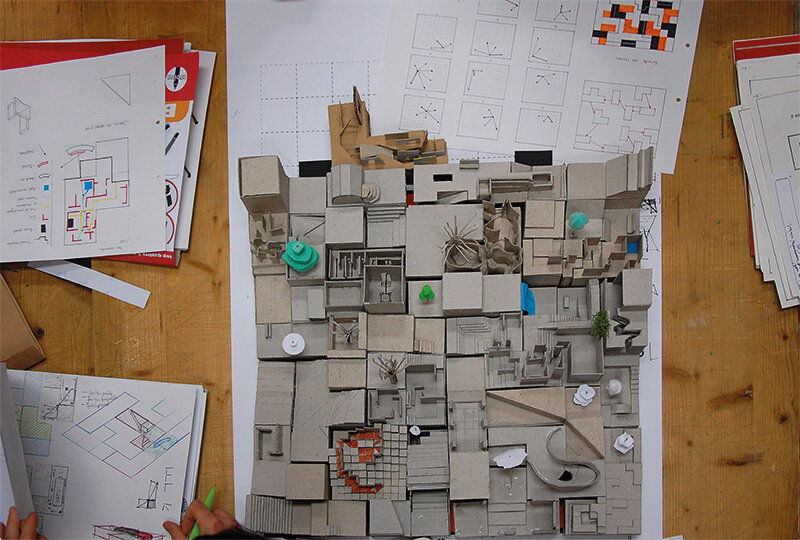

| La noi, la arhitecții generațiilor post-structuraliste, conceptul de vecinătate poartă în el acel oniric sens pozitiv din vremea lumilor pierdute, sens recuperat de critica modernismului. Mulți au încercat să-l reediteze de facto, începând cu Ebenezer Howard. Mai târziu, în 1958, studentul Piet Blom, viitor arhitect al structuralismului olandez, și-a numit un proiect de anul II „Locuire în oraș precum la sat”. Locuiești nu doar atunci când stai în casă, spunea Piet Blom, sugerând că trei sunt componentele locuirii: locuința, curtea și strada. În această idee, Blom a alcătuit un ansamblu de vecinătăți diverse, ce puteau fi și grupate, și înșiruite, creând ceva ce Aldo van Eyck ar fi numit un built homecoming. Locuințele lui integrate, cu succesiuni de curți, străzi și spații interstițiale dovedeau că, așa cum individul își trăiește realitatea existențială și pe cea socială împreună, în mod organic, tot așa nici între spațiul privat, cel comunitar și cel public nu există dihotomie.

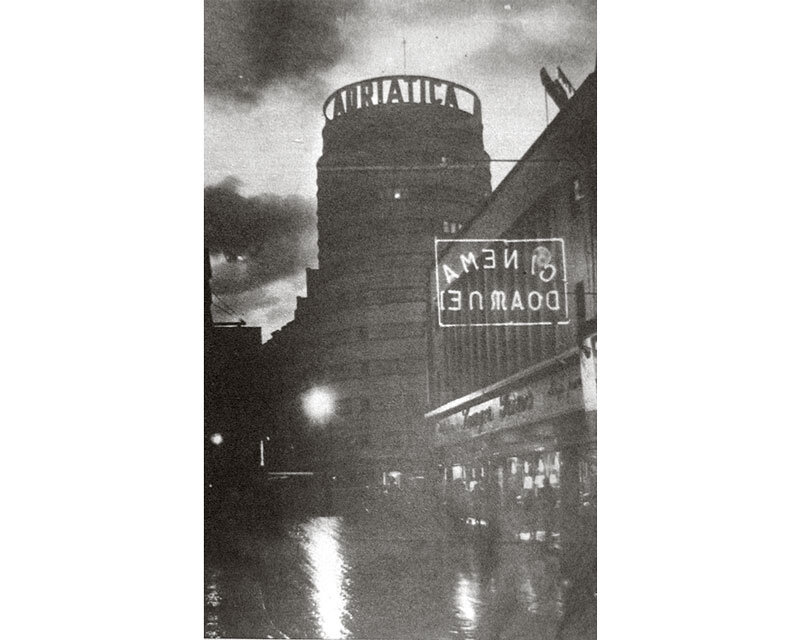

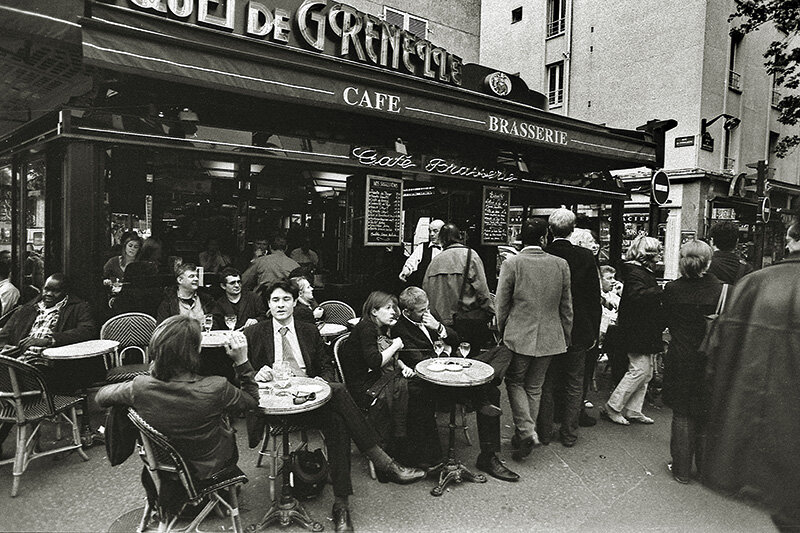

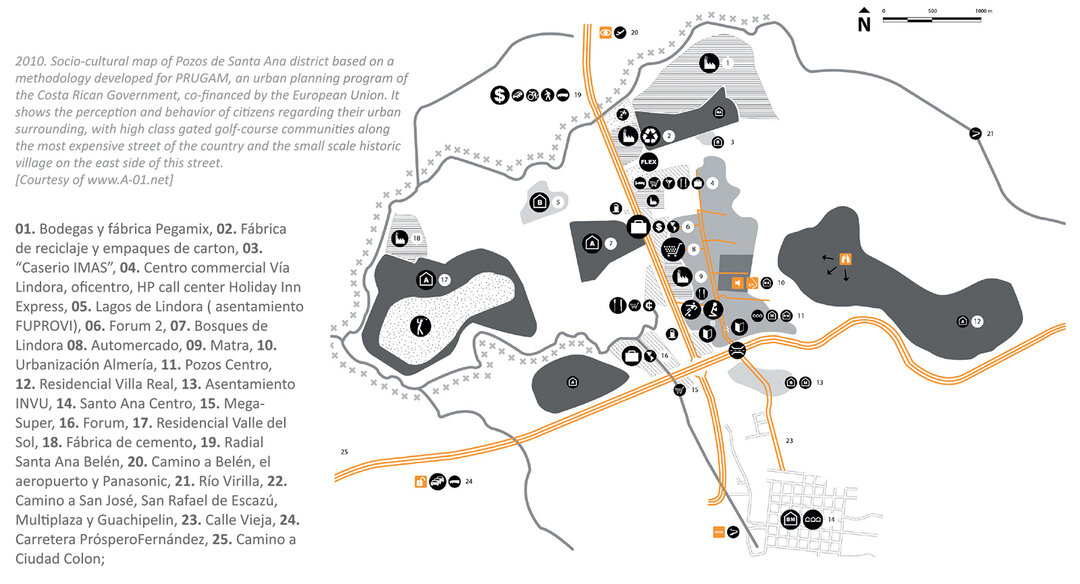

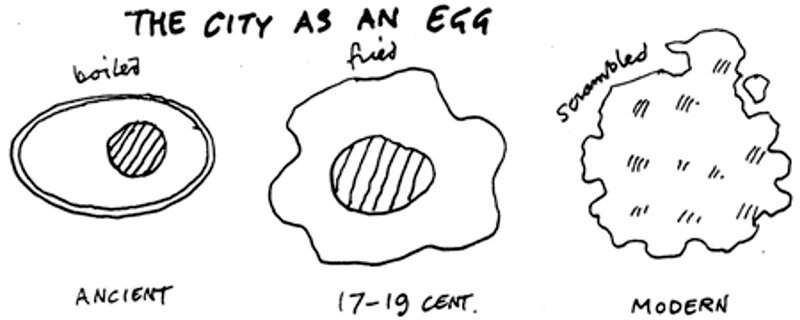

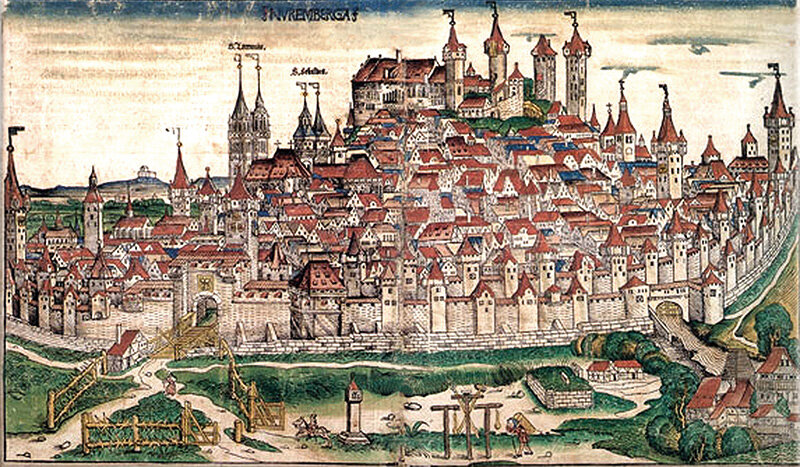

În anii ‘80, reperul urbaniștilor a fost din nou orașul medieval, elocvent teoretizat de Léon Krier, printre alții. Repere exemplare din trecut avem și noi, românii: instituția nemțească a vecinătății din Transilvania. Era o comunitate frățească teritorială care presupunea drepturi și obligații prin colaborare și ajutor reciproc între persoane și familii, grupate în spațiul unei străzi. Membrii ei beau din aceeași fântână, stăteau de gardă în timpul nopții pentru securitatea tuturora, își construiau împreună casele, se asistau în situație de boală, catastrofă sau moarte și aveau grijă de văduva și copiii rămași orfani. Oricare ar fi astăzi modelul din trecut, rural sau medieval, ideea largă de vecinătate antrenează automat nostalgii precum comunitate, valori, conștiința alterității, locuire, solidaritate, altruism, etică și alte reverii. Regretul paradisului pierdut vine de la experiențele total antagonice, trăite în orașul industrial și metropole. În localitățile părăsite de sași, noul mediu creat de „venetici” („jinari”, „moldoveni”, „poenari”, „olteni” etc., după origine, români sau țigani, după etnie) se reflectă negativ în percepția colectivă. Puținii localnici rămași de pe vremea sașilor nu se mai identifică cu satul, simt că el nu le mai aparține și deplâng vremurile când toți oamenii se cunoșteau între ei și toată lumea știa ce trebuie făcut și ce nu. De aceea, a reintegra ce se mai poate din valoarea vecinătăților d’antan în structurile urbane contemporane rămâne peste tot o temă europeană. |

| Citiți textul integral în numărul dublu 4-5 / 2014 al Revistei Arhitectura |

| We, the architects of the post-structuralist generation, endow the vicinity concept with that positive, oneiric meaning which goes back a long way and has been recovered by the critique of modernism. Many have tried to revisit it de facto, starting with Ebenezer Howard. Later, in 1958, student Piet Blom, future architect of Dutch structuralism, entitled one of his second-year projects “City Living Much like Village Living”. You live not only when you stay inside your house, Piet Blom said, suggesting that there are three components of living: the house, the yard and the street. Blom pursued his idea and put together a complex of various vicinities, which could be grouped and placed in a string, creating something that Aldo van Eyck would have called built homecoming. His integrated dwellings, with successive yards, streets and interstice spaces, proved that, just like the individual who lives his existential and social reality together, the private, the community and the public space should also evince no dichotomy.

In the 80s, urban planners’ landmark was once again the medieval city, convincingly theorized by Léon Krier, among others. We, Romanians, can also boast about exemplary landmarks in our past: we are referring to the German institution of the vicinity in Transylvania. It was a brotherly territorial community which implied shared rights and obligations, in which persons and families were bound to collaborate and help one another and which was concentrated in the space of a street. Its members drank water from the same fountain, stood guard at night to ensure everyone’s safety, built their houses together, gave each other help in the event of an illness, catastrophe or death and took care of widows and orphan children. Whichever the past model, rural or medieval, the broad idea of vicinity automatically entails nostalgic concepts, such as those of community, values, the awareness of the other, habitation, solidarity, selflessness, ethics and other such reveries. The regret of the paradise lost comes from the utterly antagonistic experiences lived in the industrial city and in metropolises. In the towns abandoned by the Transylvanian Saxons, the new environment created by “aliens” (“jinari”, “moldoveni”, “poenari”, “olteni” etc., according to their origin, Romanians or Gypsies, according to their ethnic group) is negatively reflected in the collective perception. The few inhabitants remaining since the old times no longer identify with the village, feel that it does not belong to them anymore and lament the times when everybody knew everybody and everyone knew what had to be done and what had not. For this reason, to reintegrate whatever has remained of the proximities d’antan in contemporary urban structures is a European theme. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine |

foto: Mircea Sandu