Dürer's neighborhood

Dürer's Vicinity

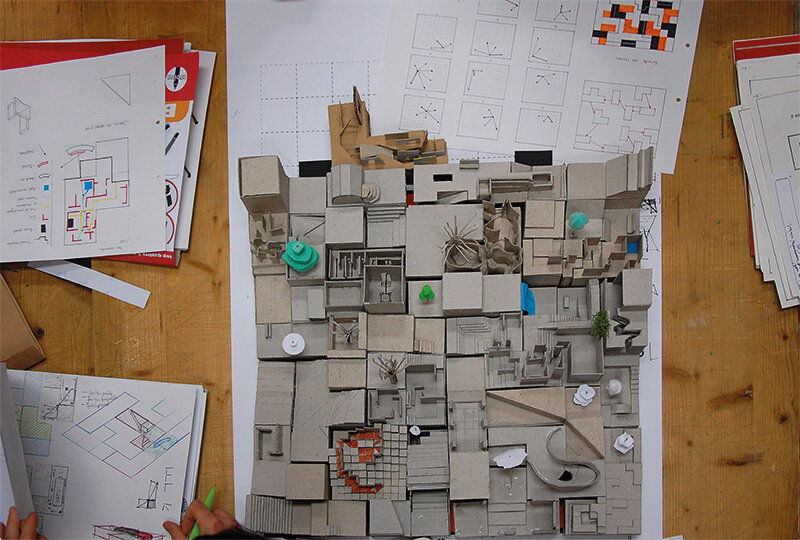

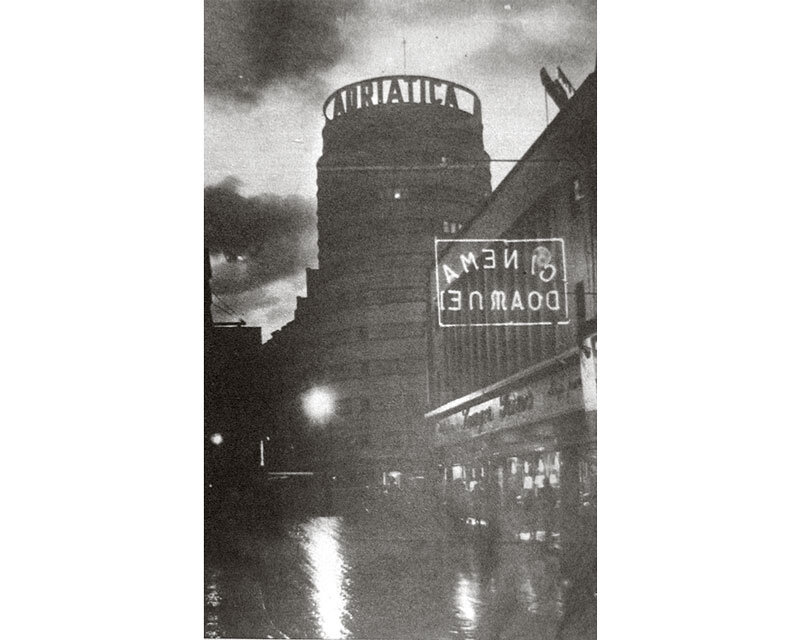

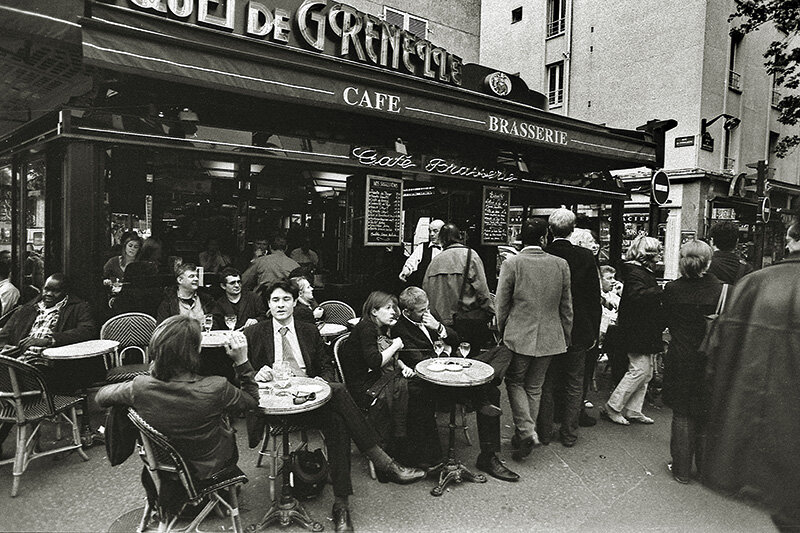

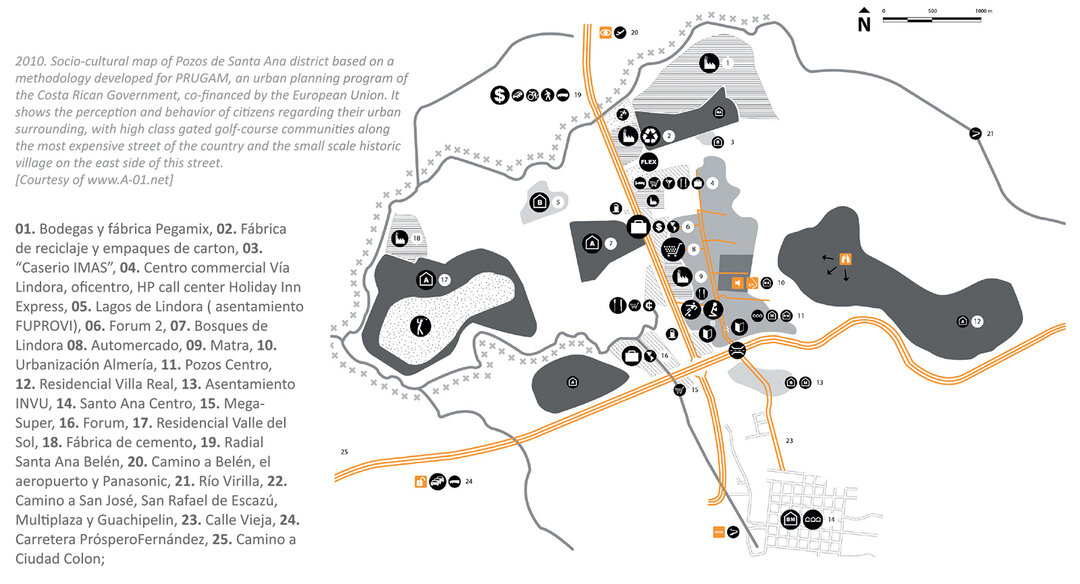

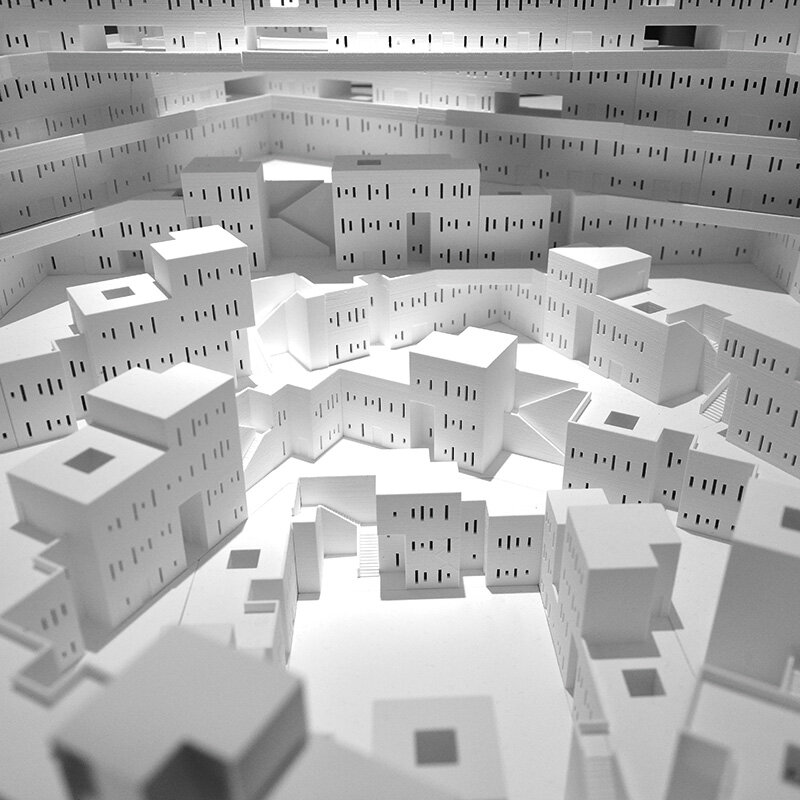

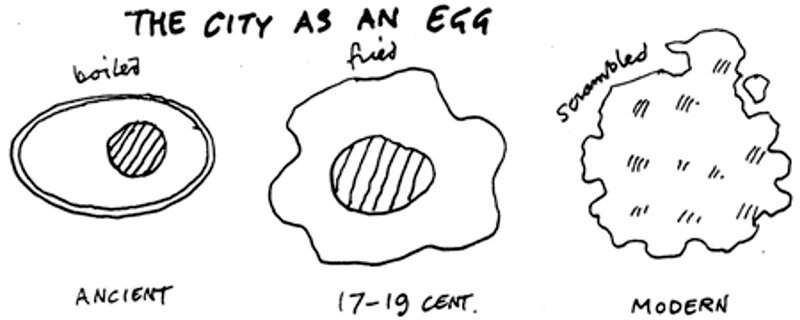

| With us, with the architects of the post-structuralist generation, the concept of neighborhood carries with it that positive oneiric meaning of the lost worlds, a meaning recovered by the critics of modernism. Many have tried to rework it de facto, starting with Ebenezer Howard. Later, in 1958, the student Piet Blom, a future architect of Dutch structuralism, called a second-year project "Living in the city as in the village". You live not only when you live in a house, Piet Blom said, suggesting that there are three components to living: the dwelling, the courtyard and the street. In this idea, Blom assembled a collection of diverse neighborhoods that could be both grouped and strung together, creating what Aldo van Eyck would have called a built homecoming. His integrated dwellings, with their succession of courtyards, streets and interstitial spaces, proved that just as the individual experiences his or her existential and social realities together in an organic way, so too there is no dichotomy between private, communal and public spaces. In the 1980s, the benchmark for urban planners was once again the medieval city, eloquently theorized by Léon Krier, among others. We Romanians also have exemplary landmarks from the past: the German neighborhood institution in Transylvania. It was a territorial fraternal community that implied rights and obligations through collaboration and mutual aid between individuals and families, grouped in the space of a street. Its members drank from the same well, stood guard at night for each other's safety, built their houses together, assisted each other in the event of sickness, disaster or death, and cared for widows and orphaned children. Whatever the model of the past today, rural or medieval, the broad idea of neighborliness automatically entails nostalgic thoughts such as community, values, consciousness of otherness, togetherness, solidarity, altruism, ethics and other reveries. The regret of paradise lost comes from totally antagonistic experiences lived in the industrial city and the metropolis. In the towns abandoned by the Saxons, the new environment created by the "Venetians" ("Jinari", "Moldavians", "Poenari", "Olteni", etc., according to origin, Romanians or Gypsies, according to ethnicity) reflects negatively on the collective perception. The few local people left over from the Saxon era no longer identify with the village, feel that it no longer belongs to them and deplore the times when everyone knew each other and everyone knew what to do and what not to do. That's why reintegrating what is still possible of the value of the neighborhoods of yesteryear into contemporary urban structures remains a European theme everywhere. |

| Read the full text in the double issue 4-5 / 2014 of Arhitectura magazine |

| We, the architects of the post-structuralist generation, endow the vicinity concept with that positive, oneiric meaning which goes back a long way and has been recovered by the critique of modernism. Many have tried to revisit it de facto, starting with Ebenezer Howard. Later, in 1958, student Piet Blom, future architect of Dutch structuralism, entitled one of his second-year projects "City Living Much like Village Living". You live not only when you stay inside your house, Piet Blom said, suggesting that there are three components of living: the house, the yard and the street. Blom pursued his idea and put together a complex of various vicinities, which could be grouped and placed in a string, creating something that Aldo van Eyck would have called built homecoming. His integrated dwellings, with successive yards, streets and interstice spaces, proved that, just like the individual who lives his existential and social reality together, the private, the community and the public space should also evince no dichotomy. In the 80s, urban planners' landmark was once again the medieval city, convincingly theorized by Léon Krier, among others. We, Romanians, can also boast about exemplary landmarks in our past: we are referring to the German institution of the vicinity in Transylvania. It was a brotherly territorial community which implied shared rights and obligations, in which persons and families were bound to collaborate and help one another and which was concentrated in the space of a street. Its members drank water from the same fountain, stood guard at night to ensure everyone's safety, built their houses together, gave each each other help in the event of an illness, catastrophe or death and took care of widows and orphan children. Whichever the past model, rural or medieval, the broad idea of vicinity automatically entails nostalgic concepts, such as those of community, values, the awareness of the other, habitation, solidarity, selflessness, ethics and other such reveries. The regret of the paradise lost comes from the utterly antagonistic experiences lived in the industrial city and in metropolises. In the towns abandoned by the Transylvanian Saxons, the new environment created by "aliens" ("jinari", "moldoveni", "poenari", "olteni" etc., according to their origin, Romanians or Gypsies, according to their ethnic group) is negatively reflected in the collective perception. The few inhabitants remaining since the old times no longer identify with the village, feel that it does not belong to them anymore and lament the times when everybody knew everybody and everyone knew what had to be done and what had not. For this reason, to reintegrate whatever has remained of the proximities d'antan in contemporary urban structures is a European theme. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine |

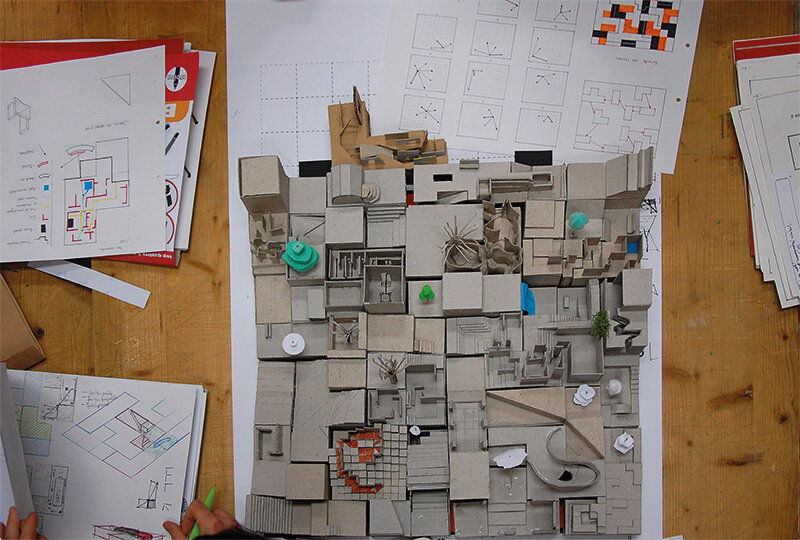

photo: Mircea Sandu