Research in the shadow of fame: Frank Gehry's career

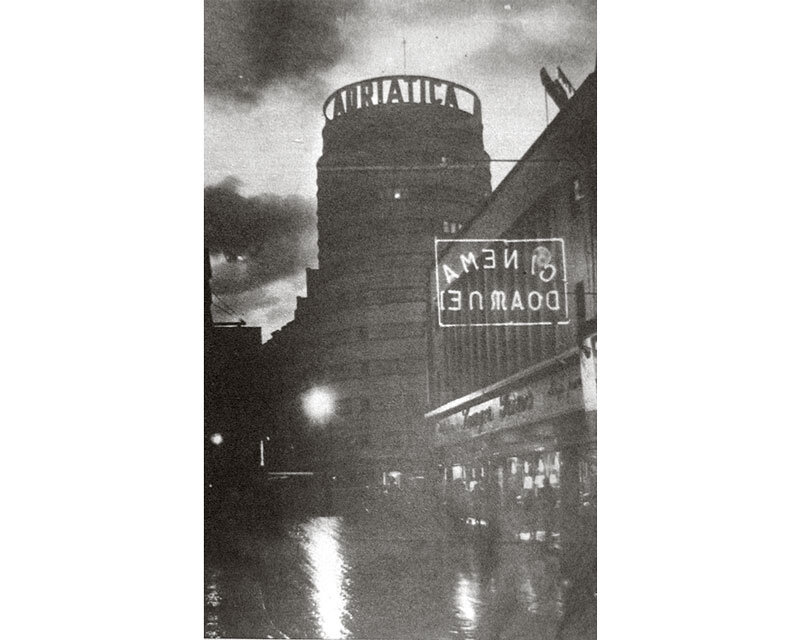

From October 8, 2014 to January 26, 2015, the Centre Pompidou is hosting for the second time a monographic exhibition on the Canadian-American architect Frank Gehry. In 19911, on the occasion of the inauguration of the American Center - the architect's first work in Paris, which became the Cinémathèque Française in 2005 - the public had the opportunity to get to know some of his European projects. Today, the scenario is repeating itself, as in October 2014 the doors will open2 on another emblematic building, the Louis Vuitton Foundation, an impressive presence of curved glass and Ductal®, in the northwest of the French capital. To mark the occasion, curators Frédéric Migayrou and Aurelien Lemonier bring to the public a comprehensive retrospective of Frank Gehry's career. Process models, drawings, interviews and films, presented in eight separate sections (six dedicated to architecture, one to digital tools research, and the last one reserved for urban planning projects less known to the general public), recompose the complex journey of one of the greatest contemporary architects. Here are some highlights:

The notoriety Frank Gehry enjoys today came late in his career. Although he had some media success in the early 1970s as the designer of a series of cardboard furniture called Easy Edges, it wasn't until 1978 that his talent as an architect was fully recognized. It all began a few blocks off the Pacific in Santa Monica, where a curious silhouette appeared in the California suburban landscape. Gehry was already in his 50s and had opened his own office in 1962, when he decided to build an extension on his own house. His typically American bungalow, built in the 1930s, was surrounded on three sides by a series of broken and rebuilt volumes. The building's new facade was made exclusively of a series of cheap, industrial and common materials, often considered ugly or inappropriate for architectural design. Metal mesh, plywood, corrugated metal surfaces or the use of asphalt on the interior shocked neighbors, who vehemently opposed the project, but excited the entire architectural community. It had been six years since the demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe3 complex, a key moment considered the beginning of postmodernism in the US. On the east coast, Philip Johnson and Michael Graves were uninhibitedly quoting the details of ancient buildings, while Robert Venturi and Charles Moore on the other side of the continent preferred to find inspiration in the local landscape. Frank Gehry, on the other hand, did not seem to belong to any clear-cut category, having no close contact with his professional environment. Instead, this residential project seemed to betray the biography of an architect surrounded by artists (Larry Bell, Ron Davis, Claes Oldenburg, Richard Serra), a practicing urban planner4 in a chaotic industrial city (Los Angeles), forced to work for years on derisory budgets, including for his own home. Over the next ten years, Gehry's residence brought him not only a large number of commissions, but also international notoriety, with the project included in a series of exhibitions including "Deconstructivist Architecture" at MOMA in the summer of 1988. A year later, he became the sixth American architect to be awarded the Pritzker Prize. Typically, this would have marked the pinnacle of a career that had already spanned more than three decades, with an impressive number of projects. But the jury urged him not to see the prize as a final crowning achievement, but as an encouragement to continue his research.

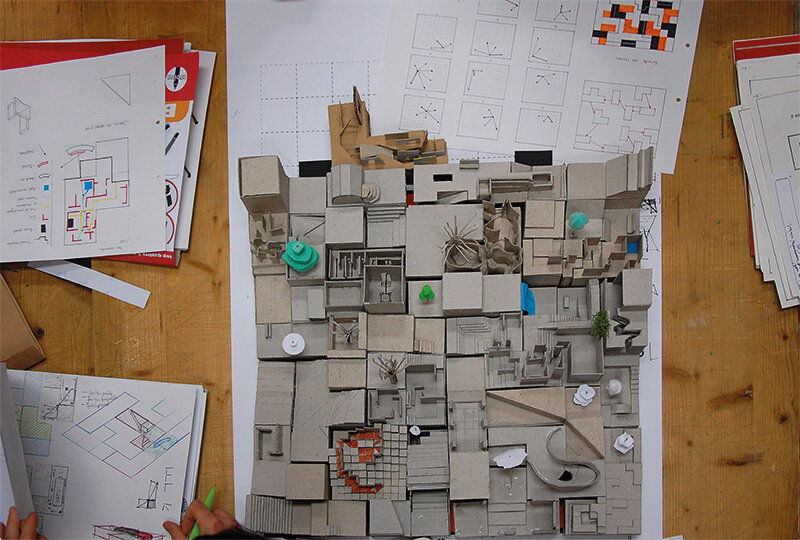

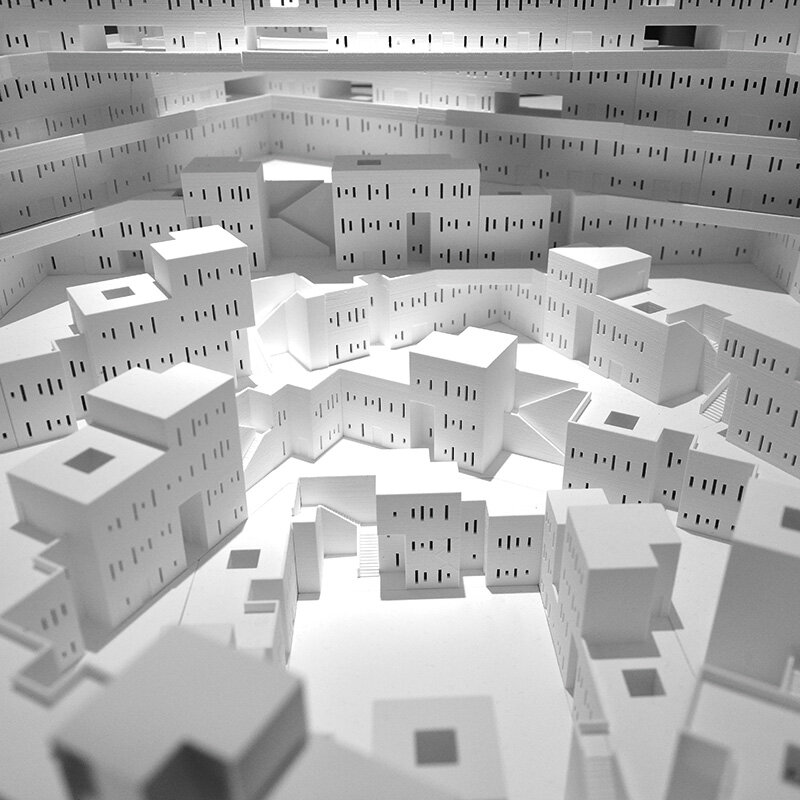

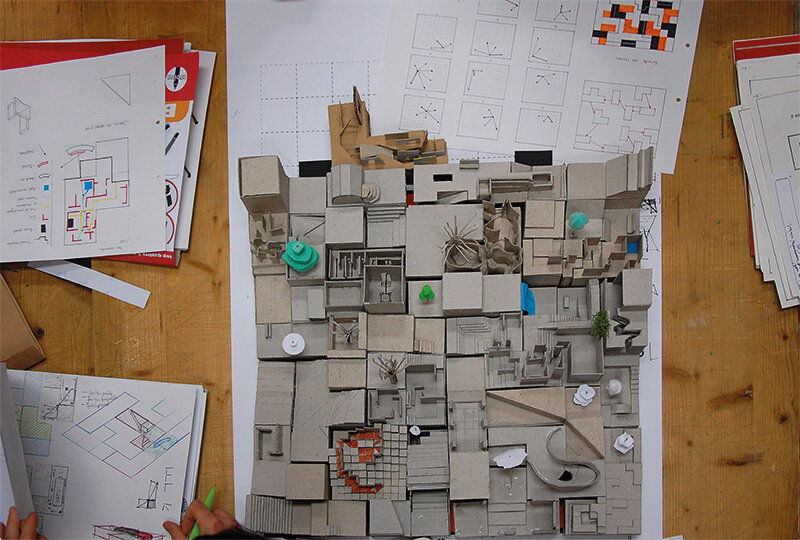

The opportunity to follow the jury's instructions came soon after he received a commission to design the private residence of wealthy businessman and art collector Peter Lewis. The project had been started in the winter of 1988, but after many interruptions, it was given a new lease of life between 1992-1995. Numerous variations were realized, and under the relentless prodding of the client, the project became increasingly experimental. In addition to complex volumetric intersections and the use of unusual materials - a typical feature of the architect's designs - Frank Gehry had the opportunity to test the potential of a new "tool". While the big American architectural firms, such as SOM, had begun to implement the use of computers, especially 2D CAD (Computer Aided Design) programs, Gehry turned instead to programs for the aeronautical and naval industries - in particular the CATIA software developed by the French company Dassault. Complex non-orthogonal shapes could be represented and manipulated directly in three dimensions. The Lewis residence thus became the ideal laboratory for analyzing the impact of computers on architectural design. Each version is first materialized as a physical model, then scanned and transformed into a 3D model. Various stages of structural optimization, analysis of technical details and cost estimation follow, testing the viability of all options. With each new version, the design becomes more and more fluid and freer in its plastic expression, yet closely followed by appropriate technical solutions. But reaching a final estimated construction cost of 80 million dollars for 2,000 square meters, the project is stopped.

The ideas developed during this period were not lost, however, but dissipated in a series of other realizations: the "horse's head" that animates the interior of the DZ Bank in Berlin (1995-2000), the undulating glass walls of the Condé Nast café in New York (1996-2000) or the dynamic metal-clad forms of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao (1991-1997). The Guggenheim Museum, a key part of a vast urban and economic regeneration project in the Basque capital, is located on the site of a former industrial factory on the banks of the Nervion river. The new cultural institution, under the aegis of the Guggenheim, is composed of a series of orthogonal volumes clad in local limestone to the south, housing the permanent collections, and to the north and also towards the river, a number of curved, undulating, metallic titanium geometries housing temporary exhibitions and in situ artistic interventions. The opening is attracting interest from across the architectural community, and among the project's supporters, Philip Johnson even calls it "the greatest building of our time". But while the general and specialized public alike were fascinated or enraptured solely by the museum's sculptural silhouette, a major technical revolution had just occurred behind the curtain. Without CATIA, the construction of this building would not have been technically possible5. The accuracy of the digital simulations was so accurately and explicitly realized that all five companies bidding to build the museum's metal structure submitted bids within one percent of each other and 18% below the original estimated budget. Thus it became clear that while the architect has greater freedom of design thanks to the computer, and the opportunity to have more control over the site, the builder has the possibility to correctly estimate the costs of a non-standard design and thus to realize increasingly complex geometries.

By the end of the 20th century and at the age of 70, Frank Gehry had already reinvigorated the architectural profession at least twice. The first through his 'analog' research into the design and construction of complex forms such as his own home, and then through his Bilbao Museum project. But the last 17 years have been a period of intense refinement for the architect. Although a number of recent projects featured in the exhibition, such as the Marques de Riscal Hotel (1999-2006), the Lou Ruvo Center in Las Vegas (2005-2010) and the design for the new National Art Museum of China (2010-2012), demonstrate the immense flexibility of the architectural vocabulary that Frank Gehry has acquired, the most eloquent examples are the Louis Vuitton Foundation (2005-2014) in Paris [see page 126] and his first skyscraper, the Beekman Tower in New York (2003-2011). The latter, also known as 8 Spruce Street or, more recently, "New York by Gehry", presents itself as an imposing metallic silhouette dominating the Manhattan skyline. Two major references have informed the design of this project: the first is the nearby Woolworth Building, designed by architect Cass Gilbert in 1913. Although this turn-of-the-century tower is best known for its neo-Gothic-inspired decoration, Gehry is particularly drawn to the effect of the rhythm of the windows. So, wishing to establish a dialog with Gilbert's design, he decided to perforate the curtain wall with a grid of large windows. The next operation was to deform this surface, like the marble folds of Bernini's 1652 statue of the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, to the point where it resembled a draped textile, enlarged to the scale of the entire city. The 76 floors clad in anodized aluminum panels thus represent a culmination of the architect's research into the design and realization of undulating metal surfaces.

On the occasion of the opening of the Louis Vuitton Foundation, the new cultural landmark of the Parisian landscape, the Centre Pompidou is presenting, in the museum's South Gallery, a complete radiography of a half-century career through more than 60 key projects. Behind an international reputation is the profile of an artist, a researcher, a builder, but above all a 21st century architect.

Notes:

1 March 13 to June 10, 1991.

2 Opened on October 27.

3 In the summer of 1972, dynamiting began on the 33 units of the Pruitt Igoe collective housing complex, realized in 1956 by architect Minoru Yamasaki.

4 After graduating in architecture from the University of Southern California. from 1949 to '51 (he received his bachelor's degree in 1954), Frank Gehry attended Harvard from 1956 to '57, where he specialized in urban planning.

5 Entretien avec Frank Gehry, in Aurélien LEMONIER, Frédéric MIGAYROU (ed.), Frank Gehry, Paris: Editions Center Pompidou, 2014, p. 61.