Tetrapolis

The vicious circle of social segregation and spatial fragmentation in Costa Rica’s greater metropolitan area

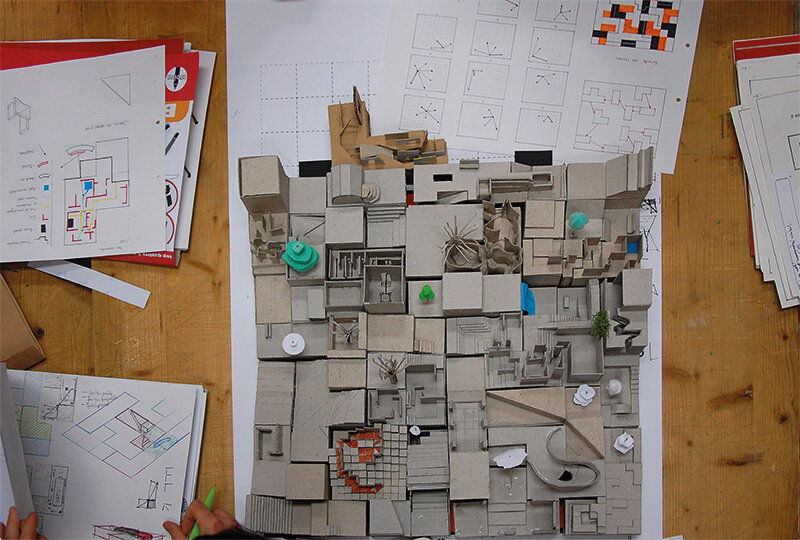

Ticollage City

| The vicious circle of social segregation and spatial fragmentation in the extended metropolitan area of Costa Rica |

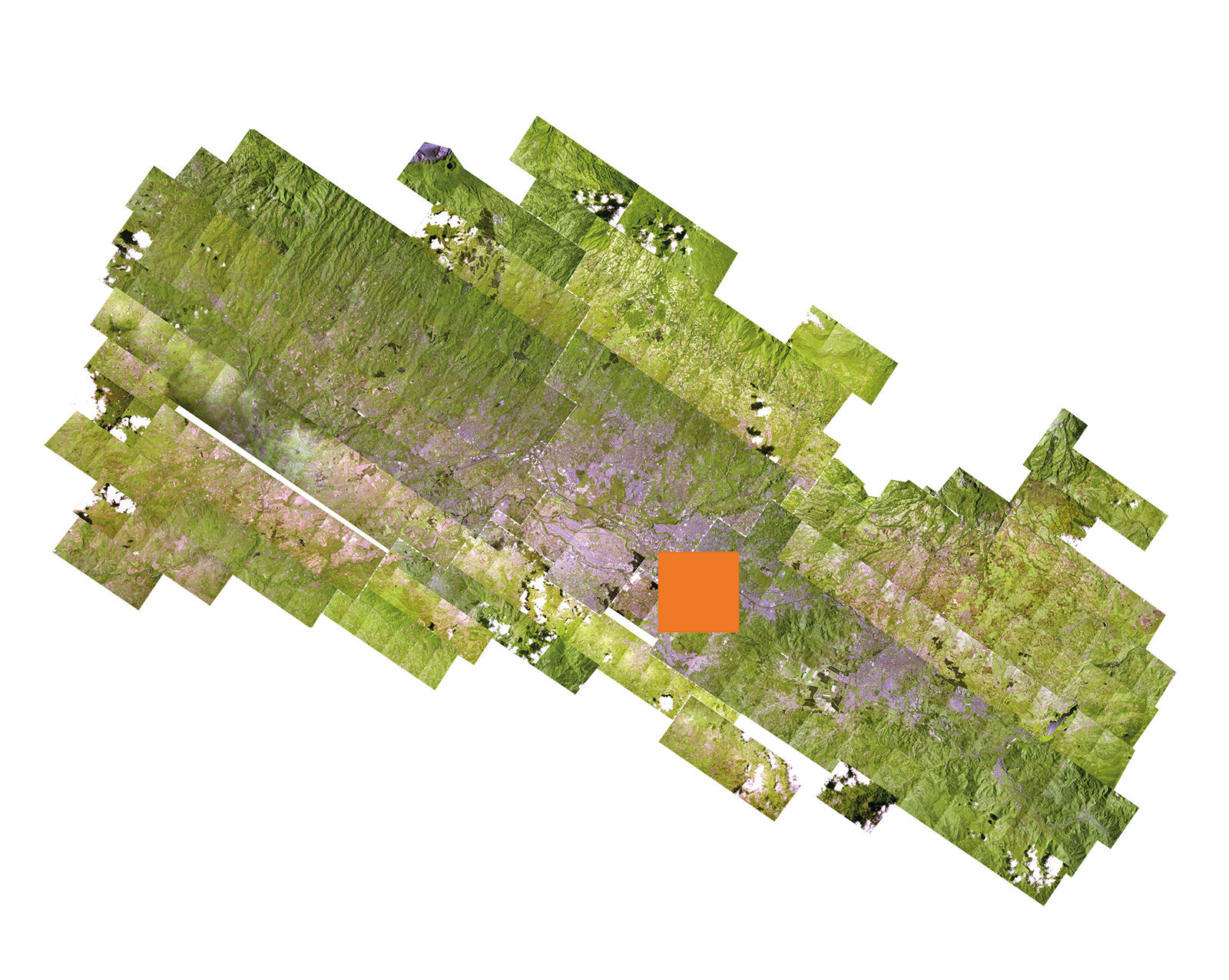

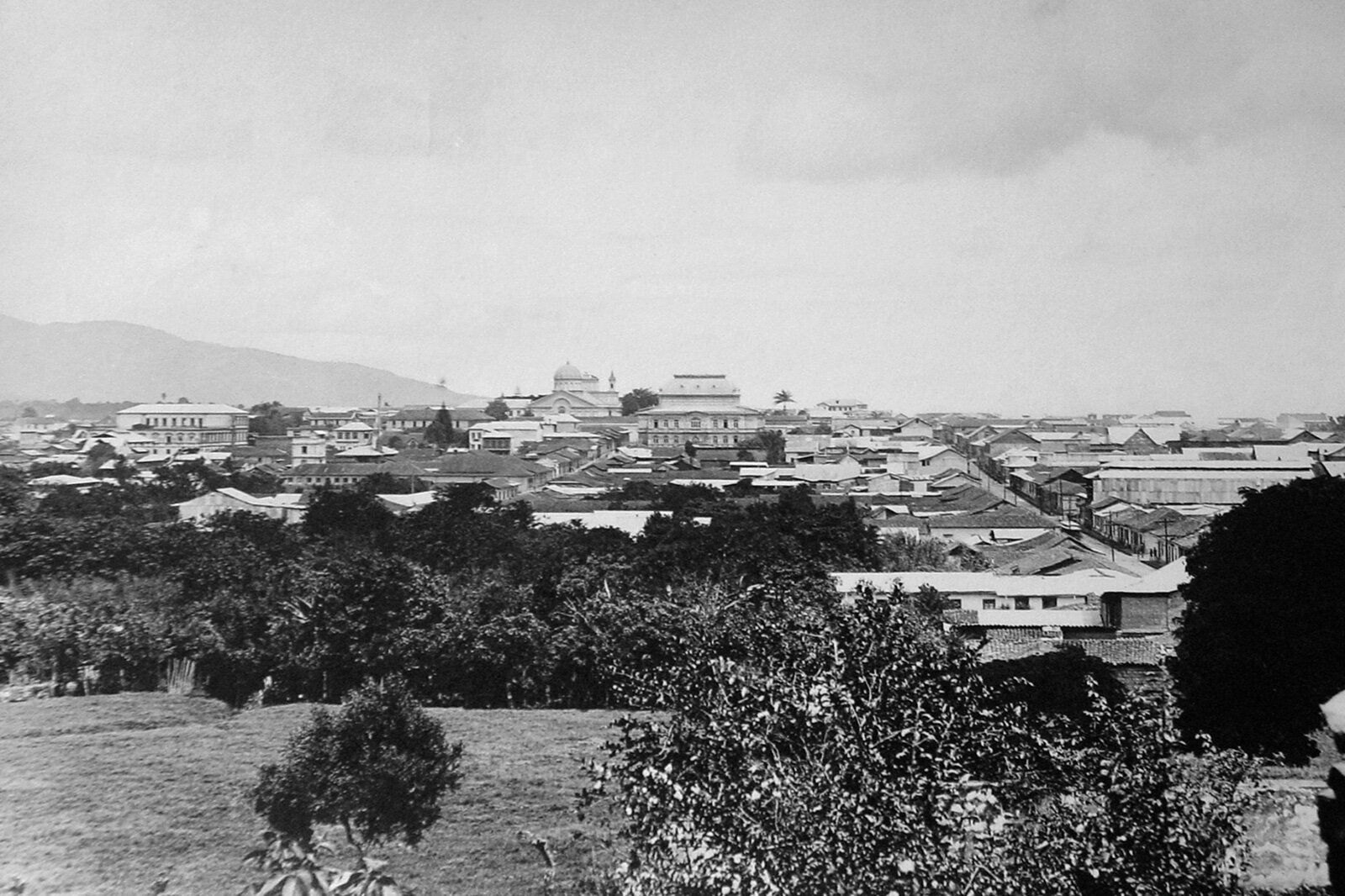

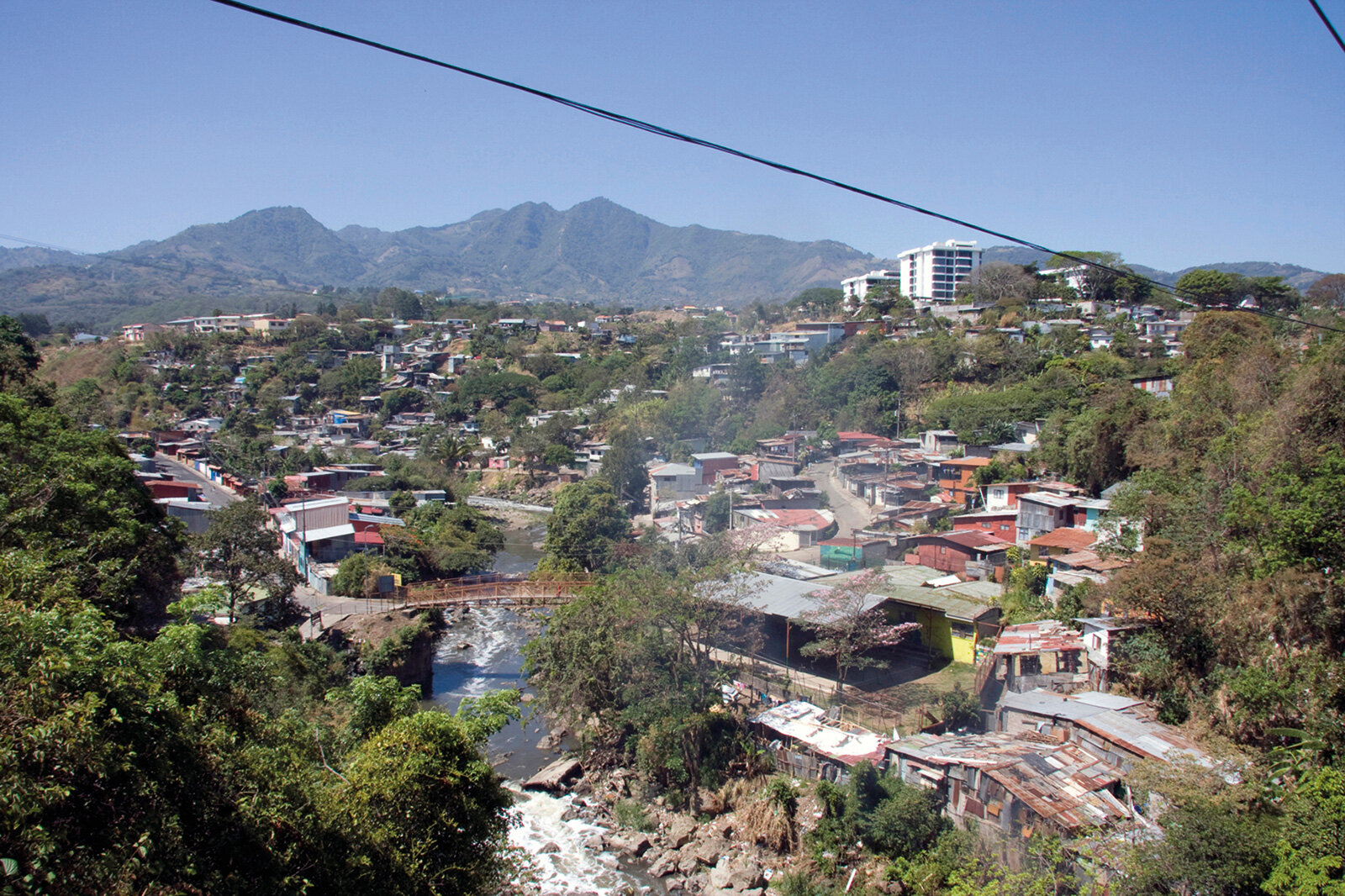

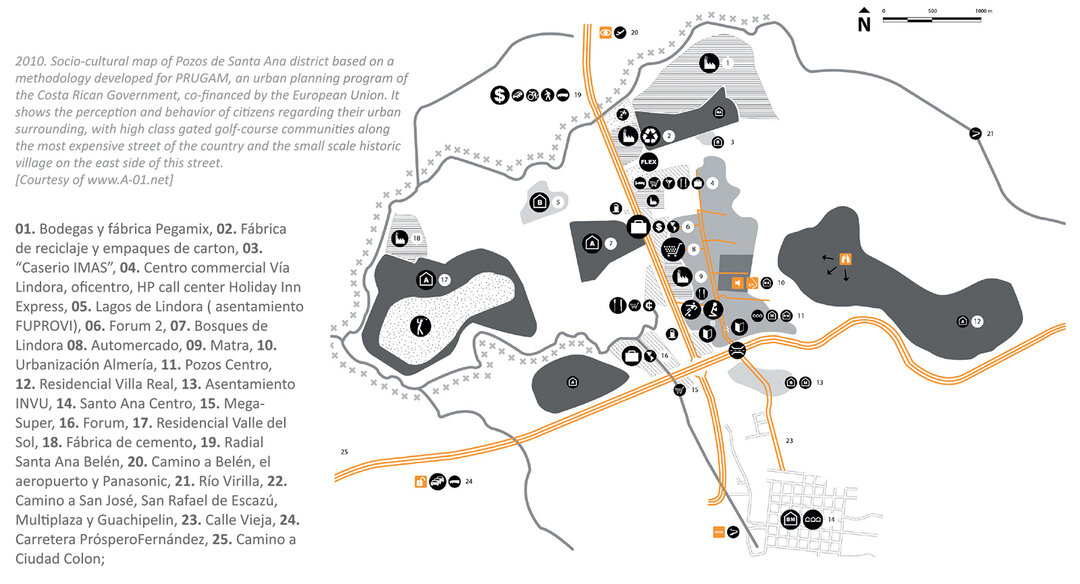

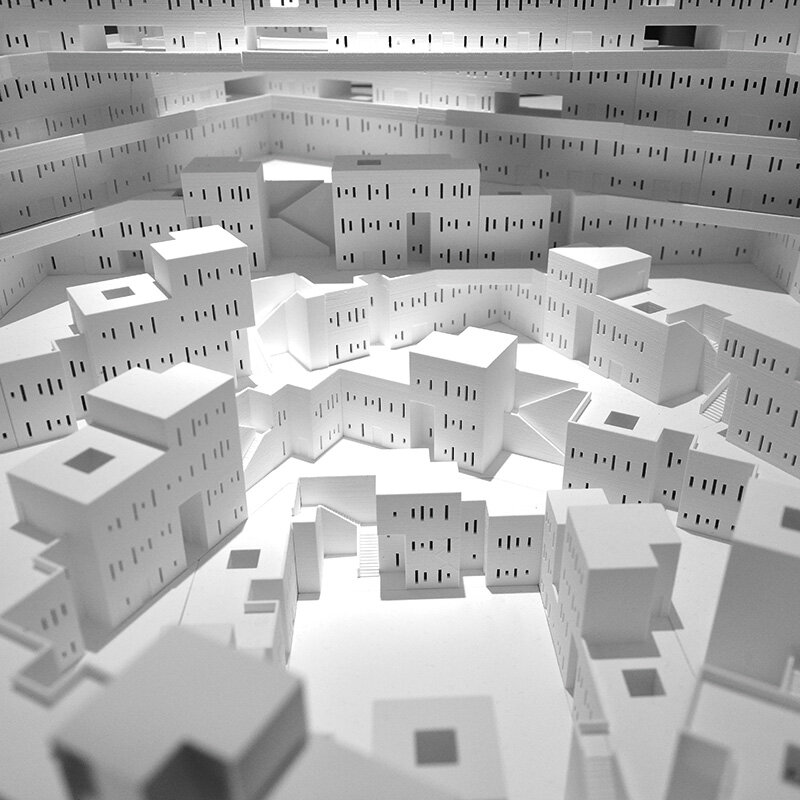

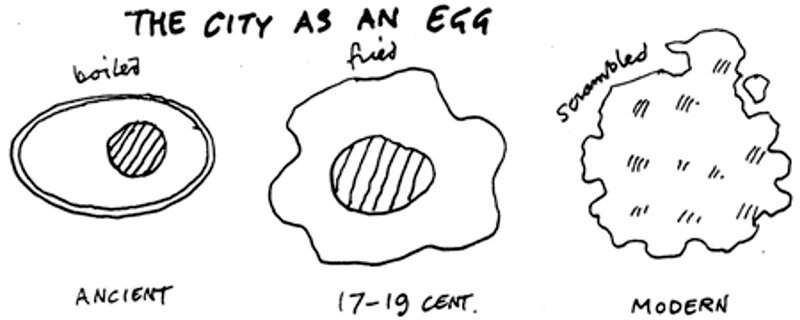

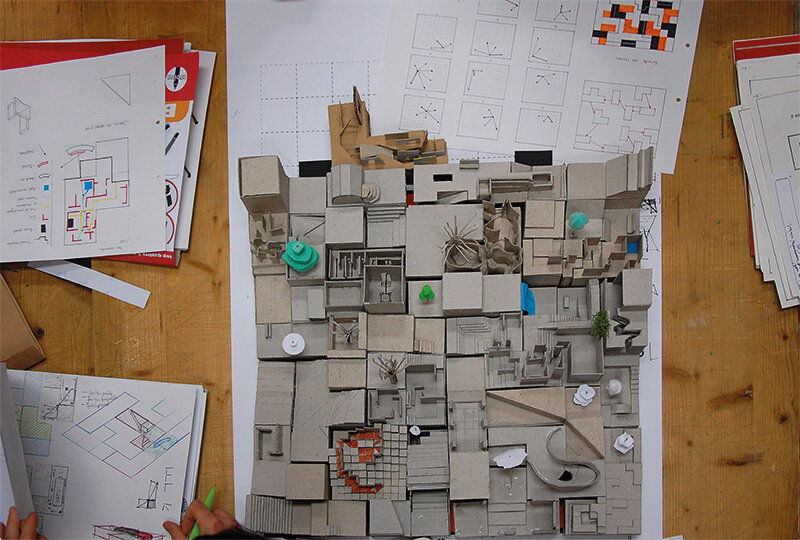

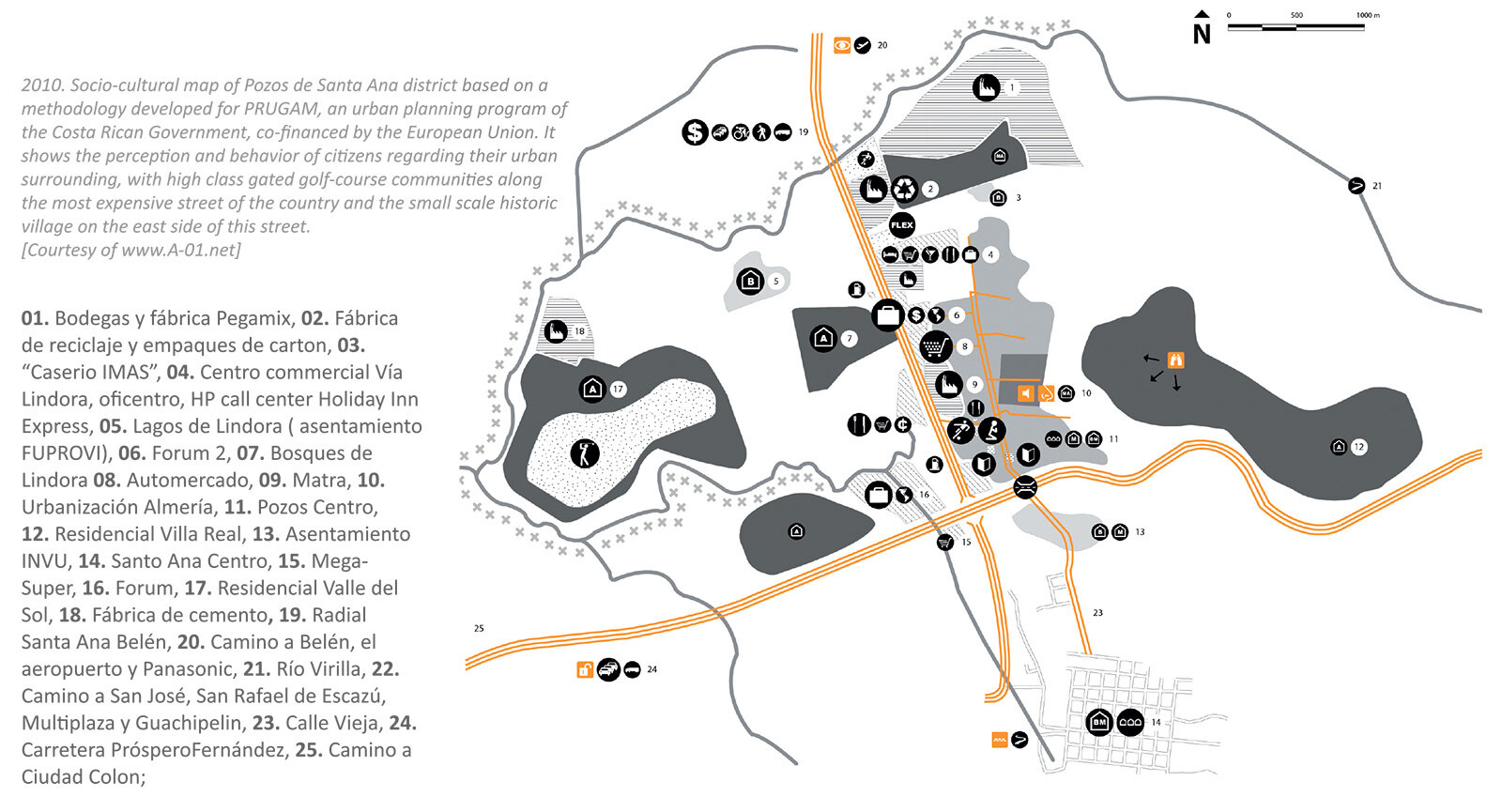

| Excerpt1 More than 64% of Costa Rica's population lives in urban areas, the majority of which live in the Extended Metropolitan Area (EMZ), made up of four cities and their peripheries, which in recent decades have begun to expand together. The culture of building up to two-storey buildings, coupled with a growing sense of insecurity, has manifested itself in the increasing trend of building gated communities on the outskirts on the site of former rural settlements, and the parallel abandonment of historic urban centers. This type of growth, intensely stimulated by the lack of urban planning instruments and regulations, has generated a number of social, economic and environmental problems. The EMZ has become a spatially fragmented hybrid, a socially segregated "rurban" area, where urban centers have been converted from mixed-component neighborhoods into commercial and institutional service centers that are generally very active by day, and abandoned at night. At the same time, rurban commuters are retreating to gated upper- or middle-class communities or to suburban fringe areas populated by members of the lower classes. Although these typologies often come into contact with each other, their inhabitants rarely interact. The spatial fragmentation, together with the separation of functions, reflects the social segregation within society (the growing gap between 'rich' and 'poor', social exclusion and inequality, as well as the lack of solidarity, social cohesion and the subsequent individualization of local culture) and at the same time deepens it, leading, among other things, to an increased sense of insecurity. As a consequence, the fragmented urban image is heightened as people implement stronger 'security' measures, abandon public spaces and retreat into their own, individually controlled worlds, which have become so distanced from each other that public services and places can no longer fully embrace them. This vicious circle of spatial fragmentation and social segregation forms the downward spiral of quality of life in Costa Rica's urban, "rurban" or former urban areas. Fields of potential Costa Rica is generally known for the purity of its natural setting, agricultural products or protected tropical rainforests. However, more than 64% of Costa Rica's population - known as Ticos - currently live in urban areas, which is well above the world average (50%) but below the average for Latin America (80%), the most urbanized region in the world2. The vast majority of the urban population lives in 4% of the country's territory3: the Extended Metropolitan Area (EMZ), made up of the historic cities of Alajuela, Cartago, Heredia, San José and their respective metropolitan areas. An aerial perspective of the MME zone dramatically illustrates a reality that Rem Koolhaas once described as "fields of potential" in a neoliberal development culture4 or what Mike Davis called "parachute urbanism"5. The conglomerate is about 1.5 times the size of Los Angeles, but has only two-thirds of its population and is a spatially fragmented and socially segregated 'rurban' hybrid. Individual cities have expanded to replace former rural areas, resulting in a seemingly chaotic collage of different worlds: natural parks or farmland now border gated residential communities, slums, industrial zones, free trade zones, office parks or shopping malls. Historic city centers have remained a specific type of area among others within this typology and have to compete with their suburban rivals for inhabitants and investment. The exponential growth of suburbs is reflected in the decline of former urban centers. The modernist separation of functions and the continuous displacement of people that it has engendered have led to worrying levels of pollution, an almost absurd sense of insecurity among residents, who populate the suburbs in very small numbers, and the abandonment of historic urban centers at night. Most of the buildings and capsule structures are protected by armies of guards and dogs, cameras, barbed-wire fences or electric fences. Costa Rica's image of a nature-loving and peace-loving country is contradicted and practically caricatured by its cities. The most dramatic consequences can be seen in the capital San José, where there are 1.2 million "users" during the day6 and only 50,000 at night7. The capital is still home to Costa Rica's most important public sector institutions and iconic architecture, but most of the historic buildings have been demolished to make way for the parking lots needed by rural commuters and their car fleets. The vicious circle of spatial fragmentation and social segregation Spatial fragmentation along functional lines across the vast expanse of the MSA is a physical manifestation of social segregation within society (widening the gap between rich and poor, inequality along class gender, age, ethnic origin or other personal characteristics, social exclusion, as well as the lack of social cohesion and the consequent individualization of local culture), which at the same time deepens it, leading, among other things, to an increased sense of fear. This in turn increases the fragmentation of the 'rurban' landscape as people implement extreme 'security' measures (fences, alarms, barbed wire, armed guards, etc.), abandon public spaces and retreat into their own, individually controlled worlds, which have become so far removed from each other that public services and spaces can no longer contain them in their entirety. This vicious circle of spatial fragmentation and social segregation forms the downward spiral of the quality of life in Costa Rica's urban, "rurban" or former urban areas. From a culture of solidarity, the culture of the MMEs has become one of individualism (less civic participation and greater social exclusion) and consumerism, which leads people to spend more time in shopping malls and less in public parks and squares. Moreover, the territorial separation of functions promotes and enforces mobility. The increasing use of personal cars has led to worrying levels of traffic congestion, environmental pollution and considerable loss of economic and social capital due to time spent on the roads. For those who cannot afford individual means of travel, public transport remains inefficient. A new urban culture The need to rethink the role of urban centers and their interdependence within the MMEZ as a polycentric conglomerate is obvious, but a number of government systematization programs and zoning methods have so far failed. A new urban development can only be achieved by generating a 'new' urban culture, which entails changing the negative aspects of the present culture: reversing the culture of fear, consumption and mobility. The vicious circle of spatial fragmentation and social segregation of the MME must be broken by stimulating interaction between the different urban worlds and by investigating public spaces that are currently neglected, in order to make them more competitive and attract a wide diversity of people again. There is a need to create mechanisms to encourage citizen participation and to raise awareness of the key issues and potential solutions among the various stakeholders in contemporary rural society. At the same time, positive cultural manifestations should be supported, for example by providing financial, logistical or infrastructural support for temporary events (traditional or contemporary, formal or informal) that can stimulate a different perception and use of public space, organized by community organizations or public institutions. The use of spaces and higher population densities contribute to an increased sense of safety and a decrease in street crime. The most important aspect, however, is to create a new urban culture that involves limiting chaotic suburban sprawl and promoting compact, multifunctional urban centers with high population density and diverse composition: mixed-population cities with buildings and spaces that operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. Re-populating the historic urban centers of the MMEs, including Costa Rica's capital, San Jose, requires the development of housing and urban programs for all sectors of the population located near or within commercial centers. At the same time, rural areas within the MMEZ, located outside the densified urban nodes, should be strengthened to produce and provide food on convenient terms to the citizens of the rurban conglomerate. A comprehensive urbanization process should combine top-down and bottom-up initiatives and promote citizen participation for both permanent and temporary uses, thereby reinforcing the right to an open, shared and inclusive urbanity that mirrors the (new) culture that inhabits it. The 140 years of architectural and urban development in Costa Rica can be contemplated in the national pavilion at the 14th International Architecture Biennale in Venice until 23 November 2014. The pavilion was organized and curated by the authors of this article together with a multidisciplinary group of national and international collaborators. |

| Notes: 1 This article is based on studies carried out by Marije van Lidth de Jeude and Oliver Schütte over the last eight years, partly together with FLACSO (Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences) for PRUGAM (Project for Regional Urbanization of the Extended Metropolitan Area), implemented by the Costa Rican government between 2004-2009 and co-funded by the European Union. A large part of this work was published in the volume: van Lidth de Jeude, Marije and Oliver Schütte. GAM(ISMO) Cultura y DesarrolloUrbano en la Gran ÁreaMetropolitana de Costa Rica. Cuaderno de CienciasSociales 155. San José: FLACSO, September 2010. The free version of this publication can be downloaded at: www.flacso.or.cr/fileadmin /documentos/2010/Cuaderno_155.PDF 2 UN-HABITAT (2012).State of the World's Cities 2012/2013. Nairobi: UN-HABITAT, p. 25-28, 148. 3 FLACSO (2007).Final Report of the Social Study for PRUGAM. San José: FLACSO. 4 Koolhaas, Rem and Bruce Mau, OMA (1995).S, M, L, XL. New York: Monacelli Press. 5 Davis, Mike (2000). Magical Urbanism. Latinos Reinvent the U.S. City. London: Verso, p. 62. 6 Ministry of Transportation and Public Works of Costa Rica, 2008. 7 FLACSO (2007).Final report of the social study for PRUGAM. San José: FLACSO. |

| The vicious circle of social segregation and spatial fragmentation in Costa Rica's greater metropolitan area |

| Abstract1 In Costa Rica more than 64% of the population is living in urban areas, the majority in the Greater Metropolitan Area (GAM) composed of four cities and their peripheries, which, in recent decades, have started growing together. The culture of constructing buildings of maximum two floors, together with an increased perception of insecurity, has led to a preference of residing in gated communities in the suburban periphery - where they substitute formerly rural uses - and the parallel abandoning of the historical urban centers. This type of growth, largely stimulated by a lack of planning tools and regulations, has led to social, economic and environmental problems. The GAM has become a spatially fragmented and socially segregated "rurban" hybrid where the urban centers have been converted from mix use neighborhoods to commercial and institutional service hubs that are mostly active during the day but largely deserted at night. At that time, the rurban commuters withdraw to the high to middle class gated communities or low class marginalized areas in suburbia. Although these typologies often border each other, their inhabitants hardly interact. The spatial fragmentation with its separation of functions is a reflection of the social segregation within society (the growing gap between "rich" and "poor", social exclusion and inequality, as well as a loss of solidarity, social cohesion and the subsequent individualization of the local culture) and at the same time increases it, leading amongst others to a higher perception of insecurity. Consequently, the fragmented urban image is augmented, as people implement stronger measures of "security", abandon public spaces and withdraw themselves into their own and individually controlled life worlds that have grown so distant from one another that public services and places are no longer capable to reach them all. This vicious circle of spatial fragmentation and social segregation forms a downward spiral of life quality within the Costa Rican urbe, rurbe or ex-urbe. Nevertheless, today more than 64% of the Costa Rican population - called Ticos - is qualified urban; well above global average (50%) but below Latin American (80%), the most urbanized region worldwide2. The large majority of these urbanites lives within 4% of the countries territory3: the Greater Metropolitan Area (GAM), composed of the historic cities Alajuela, Cartago, Heredia, San José, and their respective metropolitan areas. Looking at the GAM from above dramatically illustrates what Rem Koolhaas once described as "fields of potential" in a neoliberal culture of development4, or what Mike Davis referred to as "airdrop urbanism"5. The conglomerate measures roughly 1.5 times the size of Los Angeles with only two-thirds the amount of inhabitants, displaying a spatially fragmented and socially segregated rurban hybrid. The individual cities have expanded outwards to substitute rural uses, resulting in a seemingly random collage of scattered life-worlds: nature parks or agricultural fields now border high-end gated residential communities, slums, industrial areas, free trade zones, office parks or shopping malls. The historic urban centers remain as one typology amongst many and have to compete with their suburban rivals for inhabitants and investments. An exponential growth in suburbia is mirrored by the decline of the former urban cores. The modernist separation of functions, and the continuous mobilization of people it caused, has led to preoccupying levels of environmental pollution, as well as an almost absurd perception of insecurity in the contemporary low-density rurban periphery as well as the (by night) abandoned historic urban centres. The majority of buildings and capsular developments is protected by an army of guards and dogs, cameras, barbed wires or electric fences. The image of Costa Rica as a nature- and peace-loving country is contradicted and caricatured in its cities. The most extreme consequences can be seen in the capital San José, with 1.2 million "users" daily6, who leave behind a resident population of only 50,000 at night7. The capital still houses most of the public sector institutions and emblematic architectures of Costa Rica, but many historic buildings have been erased to make space for parking lots that serve the fleet of vehicles required by the rurban commuters. The vicious circle of spatial fragmentation and social segregation The spatial fragmentation in terms of a separation of functions distributed over the vast terrain of the GAM, is a reflection and physical expression of social segregation within society (the growing gap in the distribution of wealth between classes; inequality based on class, gender, age, ethnicity or other personal characteristic; social exclusion; as well as the loss of social cohesion and consequent individualization of the local culture) but also increases it and creates a sense of fear. This, in turn, augments the fragmentation of the rurban landscape, as it entails that people apply extreme measures of "security" (fences, alarms, barbed wire, armed guards, etcetera), abandon public spaces, and withdraw into their own - individually controlled - life worlds, which have spread so widely that they can no longer be reached by the existing public services and spaces. This vicious circle of spatial fragmentation and social segregation forms the downward spiral regarding life quality within the Costa Rican urbe, rurbe or ex-urbe. The culture of the GAM has turned from a culture of solidarity into a culture of individualism (less citizen participation and more social exclusion) and consumerism, which attracts people to spending more time in shopping malls instead of public parks and squares. Moreover, the separation of functions on territorial scale promotes and necessitates mobility. The increased use of private vehicles has generated worrisome levels of traffic congestion and environmental pollution as well as a huge loss of economic and social capital due to time spent on the roads. Public transportation for those who cannot afford individual mobility remains inefficient. A new urban culture A need to rethink the role of the urban centers as well as their interdependency within the GAM as a polycentric conglomerate is evident, but a series of governmental planning and zoning approaches have failed until now. A new urban development can only be achieved by generating a "new" urban culture, which requires a change in the negative aspects of the current one: reverse the culture of fear, consumption and mobility. The vicious circle of spatial fragmentation and social segregation of the GAM needs to be broken by stimulating interaction between the different urban life worlds and investing in the currently neglected public spaces, in order for those to become more competitive and to attract again a diversity of people. It requires the creation of mechanisms that encourage citizen participation and a process of raising awareness about the key problems and potential solutions amongst the different stakeholders of the contemporary rurban society. At the same time positive cultural expressions have to be supported. For example, by providing financial, logistical or infrastructural support to the realization of temporary events (traditional or contemporary, formal or informal) that can stimulate a different perception and use of public space, organized by community organizations or public institutions. The appropriation of spaces and higher population densities contribute to an increased perception of safety and actual decrease in the number of street crimes. Most of all, the creation of a new urban culture requires the containment of suburban sprawl and the promotion of compact multifunctional city centres with a high-density and diverse population: mixed-use cities composed of buildings and spaces that function 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. Repopulating the historic urban centres of the GAM, including Costa Rica's capital San Jose requires a diverse supply of housing and urban programs for all sectors of the population close to or within the centres of employment. At the same time, the rural uses within the GAM, outside of the densified urban nodes, should be strengthened in order to produce and supply food at short range for the citizens within the rurban conglomerate. An integral urban planning process should combine top-down with bottom-up initiatives and promote citizen participation for both temporary as well as permanent uses, thus fomenting the right to an open, shared and inclusive urbanity as a mirror of the (new) culture inhabiting it. 140 years of architectural and urban development in Costa Rica can be seen in the country's pavilion at the14th International Architecture Biennale in Venice until November 23, 2014. The pavilion was directed and curated by the authors of this article, together with a multidisciplinary group of national and international collaborators. |

| Notes:1 This article is based on studies conducted by Marije van Lidth de Jeude and Oliver Schütte in the last eight years, partially with FLACSO (Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences) for PRUGAM (the Urban Regional Planning Project of the Greater Metropolitan Area), implemented by the Costa Rican government from 2004 till 2009 and co-financed by the European Union. Big part of this work was published in: van Lidth de Jeude, Marije and Oliver Schütte.GAM(ISMO) Cultura y Desarrollo Urbano en la Gran Área Metropolitana de Costa Rica. Cuaderno de Ciencias Sociales 155. San José: FLACSO, September 2010. A free copy of this publication can be downloaded at: www.flacso.or.cr/fileadmin/ documentos/2010/Cuaderno_155.PDF 2 UN-HABITAT (2012). State of the World's Cities 2012/2013. Nairobi: UN-HABITAT, pp. 25-28, 148. 3 FLACSO (2007). Final Report of the Social Study for PRUGAM. San José: FLACSO. 4 Koolhaas, Rem and Bruce Mau, OMA (1995). S, M, L, XL. New York: Monacelli Press. 5 Davis, Mike (2000). Magical Urbanism. Latinos Reinvent the U.S. City. London: Verso, p. 62. 6 Costa Rica Ministry of Transport and Public Works, 2008. 7 FLACSO (2007). Final Report of the Social Study for PRUGAM. San José: FLACSO. |