Poetic Neighborhoods - House and Stars

"In addition to making us inhabit space, architecture also relates us to time; it articulates the naturally unlimited space and gives endless time a human measure. Architecture helps us overcome the 'terror of time', to use an expression of the philosopher Karsten Harries."1

(Juhani Pallasmaa)

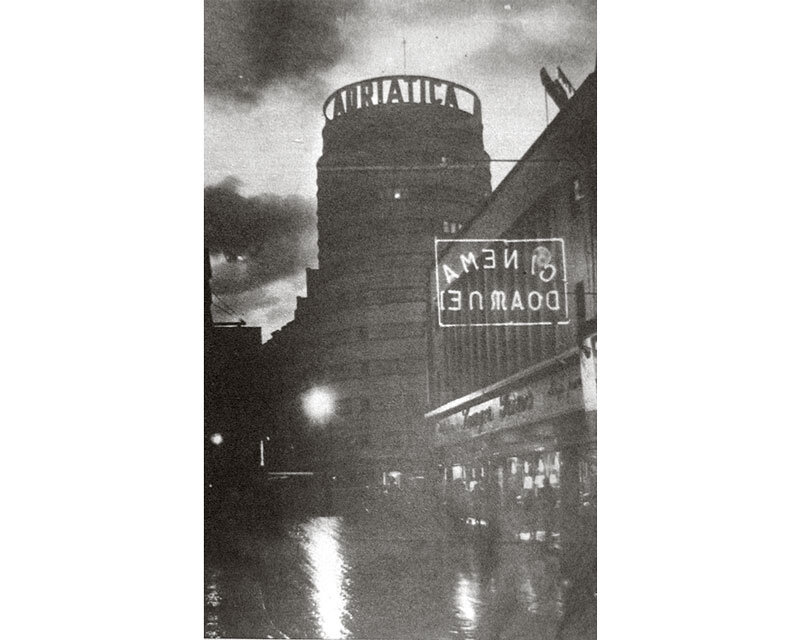

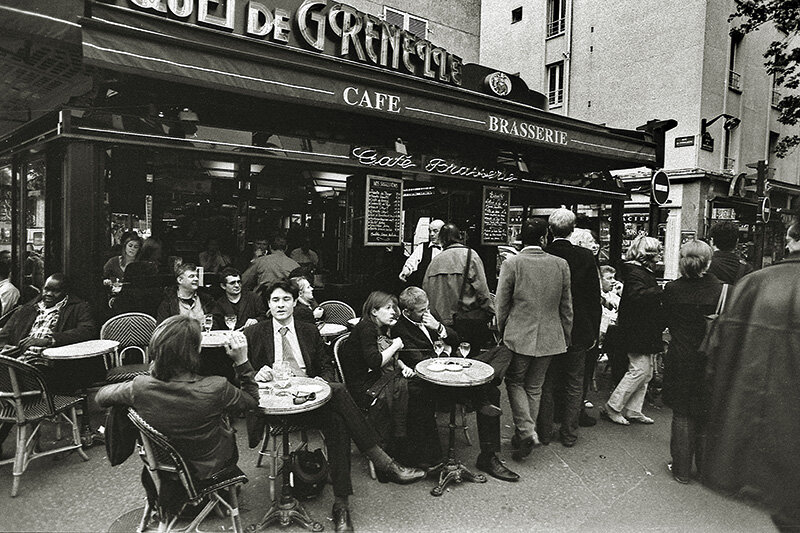

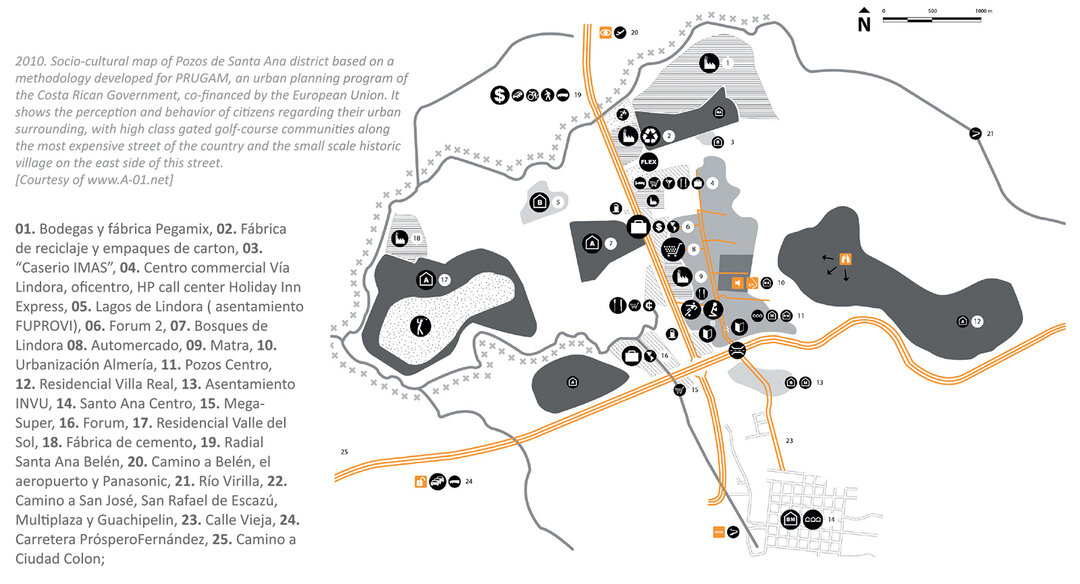

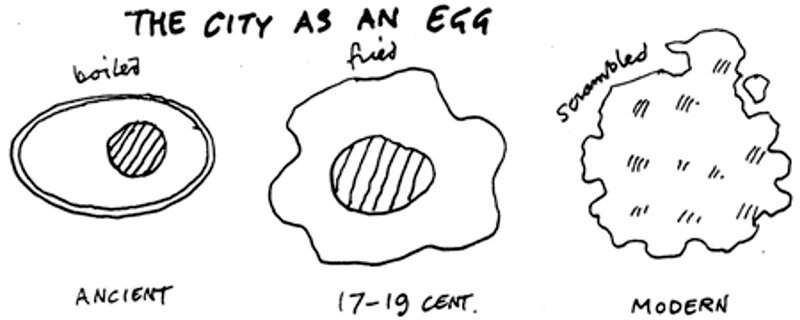

Neighborhoods... neighborhoods contextualize, anchor in a specific place and time. But being a neighbor has meant more than that in the history of architecture, it has meant recognizing shared values, subscribing to a culture, accepting hierarchies. The supreme gesture of the choice of neighborhoods was the choice of that place and time, establishing the building as the axis mundi. In contemporary times, we notice the neighborhoods as residents, usually looking at them beyond the limit of the construction, or, antithetically, as architects we approach them a priori to the construction. I wonder whether, beyond these two conventional positions, context is not an architectural determinant on a poetic level.

A particular vision belongs to one of my childhood stories, a story that illustrates self-sufficiency in a world without neighbors, at least apparently.

"Once upon a time there was a little prince, who lived on a planet2 only a little bigger than himself and who needed a friend..."3

In an archetypal way, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's fable The Little Prince4tells the story of worlds populated by a single person, with an idealistic approach to life and human nature5. The house-body couple takes on postmodern valences by redefining the dwelling, the unbounded space, in relation to the individual, creating an intimate world through singularity. In this ideal world, the limit of the 'house', of the room, no longer existed. The prince's house was literally a substitute planet for the house of identity - a metaphor of the spatial universe, a macrocosmic projection where paradoxically "Where I can see with my eyes, you cannot go very far"6 ...

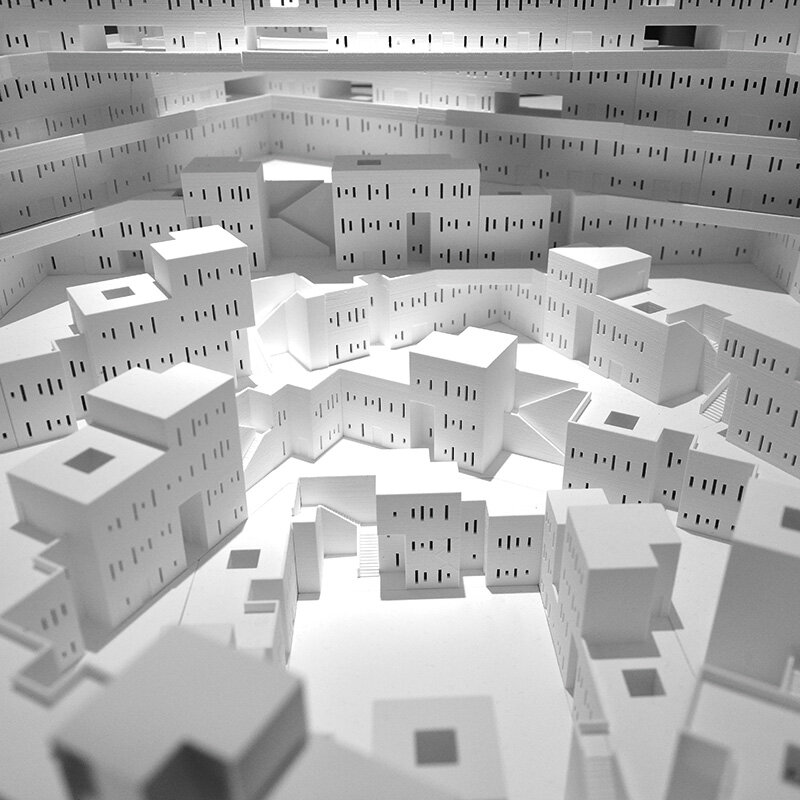

The Little Prince's World is seemingly antithetical to the highly complex, almost pictorial vision of the Invisible Cities described by Italo Calvino, cities built on the basis of architectural logic. But looking more closely, the construction of context is based on a similar logic - the logic of place. This time the worlds discovered by the Little Prince are worlds in which property boundaries disappear, in which planets are not occupied by buildings, in which places are marked on the basis of static or dynamic everyday experiences. Space is redefined by involving the character in everyday routine actions, in a theatrically 'postmodern' vision: cleaning volcanoes. Italo Calvino operates with an abundance of architectural elements, while at the opposite pole Antoine de Saint-Exupéry renounces them in support of a surrealist vision, making restrained use of pieces of furniture or tools, but paradoxically both authors conceptually project the idea of place.

It is not by chance that the representations favor the downward, gravitational perspective. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry projects a world ordered by the force of physics and subscribes, in this sense, to the vision of Kant and Hershel, who saw gravity as the transforming/ordering force of chaos. In an antithetical perspective, Newton discusses the permanent divine order as the state of things7.

The illustrations, on the other hand, anchor the cosmic, spatially contextualize "home", a world identified by the geometry of the constellation8 - the universe of asteroid B621.9 Referring to the illustrations of the first edition of the book in 1943, and the watercolours executed by the author, the critic Yoshitsugu Kunugiyama noted the similarities between the constellation B621 and the isosceles triangulated celestial configuration specific to the period in which the author lived. The representation recalls the hierarchical universe and cosmological perspectives, the perception of architectural geometry in relation to the universal order in the 17th century and the cosmic dynamics of the 18th century. In the substratum, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's knowledge of mathematics and astronomy was certainly superior as an airplane pilot and most probably included the theses of J. Heinrich Lambert10 and his graphic representations. It is no coincidence that the cover illustration of The Little Prince, the sequential presentation of the planets, redesigns the world from an astronomical perspective specific to Lambert.

"While the other animals lean toward the ground and have eyes only for it, man (the creator) turns his face toward the sky, which proposes contemplation and invites him to raise his gaze to the stars."11 (Ovid, Metamorphosis, I.V. 84-86)

This is not the only case in which the context refers to the position in the universe, the neighborhoods becoming coordinates of the house. The particular position of the stars - in terms of contextualization of architecture - is reinterpreted in the interior of the Church ofSaint-Pierre deFirminy12, realized according to Le Corbusier's original design. The central space of the nave, enclosed by the concrete shell, although introverted, with no visual connection with the neighborhood, is oriented towards the constellation Orion, a constellation visually reproduced in the perforation of the enclosure.

Similarly, Dr. Rappenglueck pointed out, referring to late Paleolithic people: 'They painted the sky, but not the whole sky. Only those parts that were particularly important to them"13. Lascaux, View of the Magdalenian Sky is the conclusion reached by researchers after 1999, discovering the particular case of the summer solstice illuminating the access to the Lascauxgallery14 . The "origin of astronomy or the hidden order of a Paleolithic work"15 has also been identified in the series of paintings of bulls on the cave walls - the 13 phases of the world and the supposed constellation of Taurus16.

Read the full text in the double issue 4-5 / 2014 of Arhitectura Magazine

NOTES

1 Juhani Pallasmaa, on Touching the World - architecture, hapticity and the emancipation of the eye, (free translation), pdf., http://www.arquitectura-ucp.com/images/PallasmaaTW.pdf, accessed: 03.03.2012.

2 "I had thus learned one more very significant fact: that his home planet was barely the size of a house!", "The planet from which the Little Prince came is asteroid B612"- Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le Petit Prince, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0300771h.html, accessed: 02/.03.2012.

3 Op.cit.

4 Ibid.

5 Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le Petit Prince, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0300771h.html, accessed: 02/.03.2012.

6 In his memoir "Terre des hommes", Antoine de Saint-Exupéry recounts the real episode behind the introduction of The Little Prince, which he experienced as an airplane pilot in December 1935. The crash in the Sahara resulted in wandering for 4 days through the desert, mirages and hallucinations - cf Schiff, Stacy. Saint-Exupéry: A Biography, New York, 1994, Da Capo. p.256-267, apud Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antoine_De_Saint-Exupery, accessed: 02.03.2012.

7 Pérez-Gómez, Alberto and Pelletier. Louise. Architectural Representation and the Perspective Hinge.

8 Shimbun, Yomiuri (2001) "A Star-tling Centenarian Theory", Daily Yomiuri, February 10, 2001, cited by Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antoine_De_Saint-Exupery, accessed: 02.03.2012.

9 "The planet from which the Little Prince came is asteroid B612"- Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le Petit Prince, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0300771h.html, accessed: 02/.03.2012.

10 Pérez-Gómez, Alberto and Pelletier, Louise. Architectural Representation and the Perspective Hinge. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1997.

11 Ovid, Metamorphosis, I.V. 84-86, free translation.

12 Le Corbusier, Saint-Pierre de Firminy Catholic Church, Firminy, Loire, France, 1970-2006.

13 Whitehouse, Dr. David Whitehouse - 'Oldest Lunar Calendar Identified', BBC News Online, Monday, October 16, 2000, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/975360.stm, accessed: 03.03.2012.

14 Lascaux, late Paleolithic, ca.15-18,000 BC.

15 Chantal Jègues-Wolkiewiez mentioned the discovery of the "Abri Blanchard", Dordogne, respectively the incisions on a small bone, associated with the calculation of the position of the moon in the Paleolithic sky, as an indication of "some notions of astronomy in very ancient historical times", "that is why it is believed that the origins of astronomy are to be found in Babylonian culture, 6.000 de ani" - "The roots of astronomy, or the hidden order of a Palaeolithic work" (in Les Antiquités Nationales, tome 37 pages 43-52), February 2007- Jègues-Wolkiewiez, Chantal - "Lascaux, View of the Magdalenian Sky", http://www.archeociel.com/Accueil_eng.htm, accessed: 03.03.2012.

16 "The Pleiades in the 'Salle des Taureaux', Grotte de Lascaux. Does a Rock Picture in the Cave of Lascaux Show the Open Star Cluster of the Pleiades at the Magdalenian era (ca 15,300 BC)?", Proceedings of the IVth SEAC Congress / Proceedings of the IVth SEAC Meeting "Astronomy and Culture". Salamanca, Spain, 3.-6. September 1996, pp. 217-225. Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca / Hergar, s.1, http://www.infis.org/downloads/mr1997cenglpdf.pdf, accessed: 03.03.2012.