The ghetto and the vitiation of urban neighborhoods

The Ghetto

The term ghetto can refer to different things1. It can represent a poor residential space2 or, as Massey and Denton3 conclude, it can describe the reality of a racially homogeneous residential space.

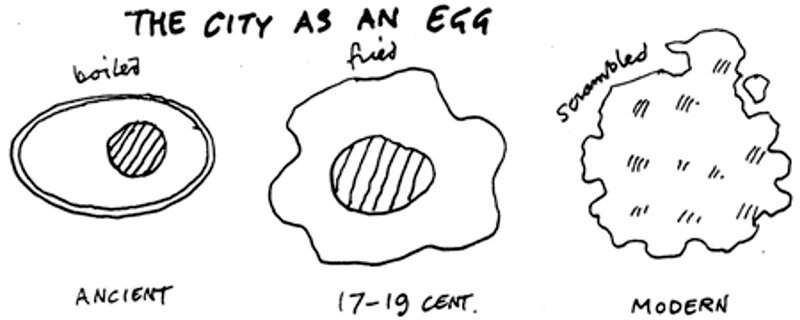

For the United States, according to Ward4, the content of the term has successively expanded and narrowed in relation to the approaches of political elites and intellectuals. Over time, ghetto took on a broad meaning describing the reality that was to embody, according to Wacquant5, the intersection of ethnically segregated newcomer and slum neighborhoods. The merging of the two means the exacerbation of certain urban 'ills' such as crime, poverty, etc. After 1945, racial enclaves were created. Thus, in response to the unwavering exclusion of whites, which acted as a shield, blacks developed and evolved in parallel.

In Japan, all the 'conditions' of the ghetto are met with reference to the buraku6 population. According to Mutafchieva7, buraku means ghetto people or simply ghetto8. The buraku population is descended from the caste considered as outcasts in Japan, a social notion dating back to the Middle Ages. The damage to the image of the buraku community is related to the bad reputation of the occupations practiced by their ancestors9. In the past, the members of this community were deprived of any rights, and their livelihood was intimately linked to the outskirts of the settlements in which they were segregated. Wacquant says that the Burakumin "suffered centuries of virulent prejudice, discrimination, segregation and violence that isolated them socially and physically"10. With the move to the cities they were funneled, against their will, into neighborhoods near garbage dumps, crematoria, prisons and slaughterhouses. For 1985, Shirasawa identifies some 3 million Burakumin concentrated in 6,000 ghettos11.

The year 1516 should also be mentioned here, when the first ghetto, the Venetian ghetto, was founded. Kessler and Nirenberg note this date to recall how the Venetian Senate decreed that all Jewish residents of the city should move behind the walls of the Nuovo Ghetto12. Ghettoization thus takes its origin as an action of enclosure, surveillance and control. The compulsory establishment of residency led to overcrowding, poverty, excessive morbidity and mortality on the one hand, and on the other hand to the emergence of a distinct cultural identity.

The ghetto to which I will refer in the text presupposes, on the one hand, the existence of an urban space inhabited mostly by a particular ethnic group (Roma, in this case), physically degraded or made up of informal settlements, which, on the other hand, minimizes contact between its members and the dominant society. The social composition is marked by poverty and stigmatized respectively, which makes the ethnic group develop and evolve in parallel with the dominant society. The following sections will provide the necessary arguments to support the theoretical and conceptual parallelism with the cases outlined above. Life in the ghetto revolves around two coordinates: integration and cohesion within and accelerating isolation from the outside13.

The space of analysis

Romania is home to many poor urban areas where several hundred to several thousand socially and geographically segregated Roma people live14. Poverty, people on social assistance, lack of education and vocational training, lack of identity documents, illegal housing, insufficient housing space, lack of utilities, high birth rates and high density, physical decay of buildings, squalor, health risks (diseases, epidemics, disabilities), the presence of disease carriers (insects and animals), crime and conflict, drugs and begging are just some of the realities of the ghetto15.

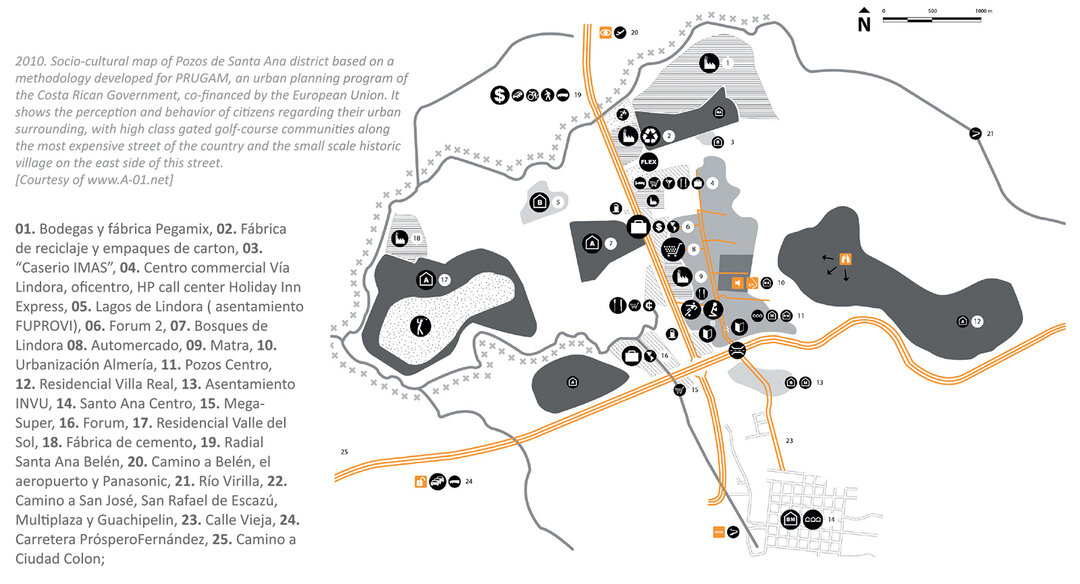

The urban ghettos on which I have focused my attention are: Craica and Horea in Baia Mare, Muncii and Speranța in Piatra Neamț, Checheci in Arad, Colonia de la km. 10 in Brăila, the ghetto next to the sewage treatment plant in Miercurea Ciuc, the Parcul Tineretului ghetto in Botoșani, the ghetto on Munții Tatra street in Constanța, the Zăvoi ghetto in Sibiu, the former G1 ghetto in Bârlad, moved to a new location on the outskirts of the city, the G4 ghetto, the Micro 19 neighborhood in Galați, Istru ghetto in Giurgiu, the former L2 ghetto in Drobeta Turnu Severin, also moved to a peripheral location, the so-called NATO ghetto in Oradea, the ghetto on Ostrovului Street in Satu Mare, Turturica in Alba Iulia, the "Berlin Wall" ghetto in Miercurea Ciuc and the Pata Rât ghetto in Cluj Napoca. To these should be added those in the capital: Aleea Livezilor, Tunsu Petre, Amurgului and Valea Cascadelor16.

Based on the data collected through an ethnographic analysis, I will argue that a typology of ghettos can be identified in Romania and, beyond this finding, their spatial presence is detrimental to the image and quality of the neighborhoods

Read the full text in the double issue 4-5 / 2014 of Arhitectura Magazine

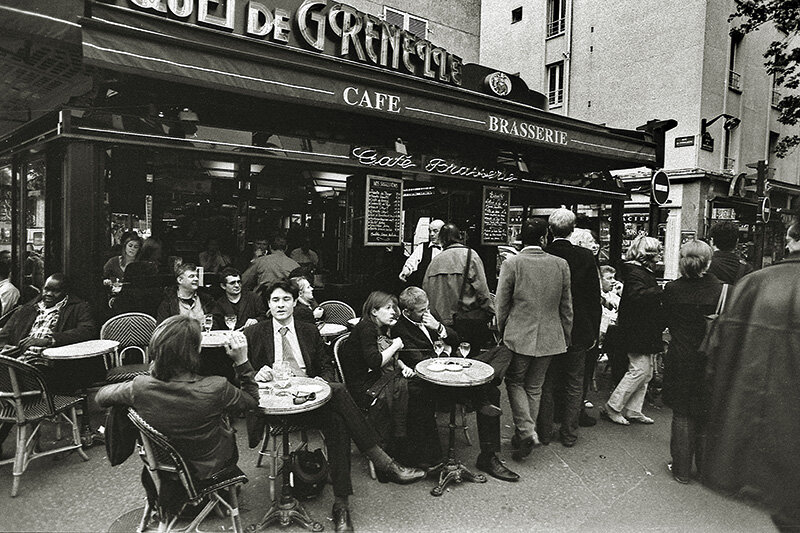

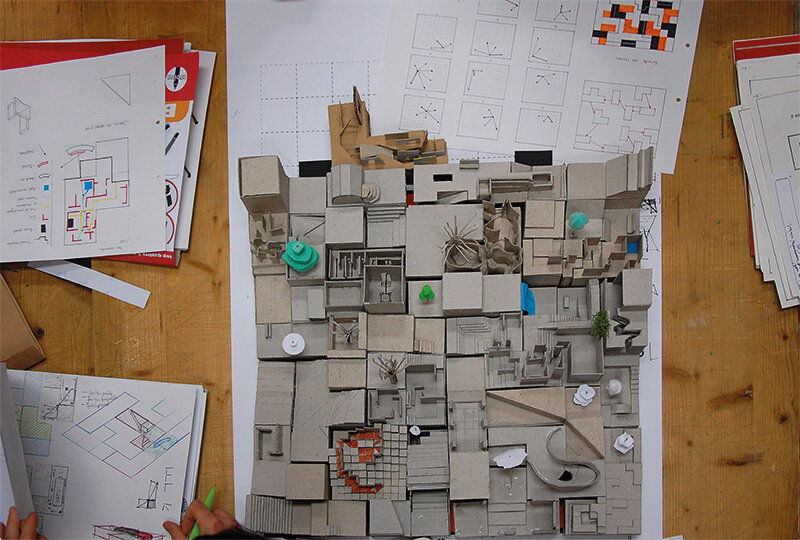

photo: Adrian BĂLTEANU

Notes:

1 Ryan Very. "Black Capitalism: An Economic Program for the Black American Ghetto", International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 2, 22 (2012).

2 William J. Wilson, When work disappears: the world of the new urban poor (New York: Knopf, 1996).

3 Douglas S. Massey and Denton A. Nancy. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1993).

4 David Ward, Poverty, Ethnicity and the American City, 1840-1925: Changing Conceptions of the Slum and the Ghetto (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1989).

5 Loïc Wacquant, 'A Janus-Faced Institution of Ethnoracial Closure: A Sociological Specification of the Ghetto', in The Ghetto: Contemporary Global Issues and Controversies ed. Ray Hutchison and Bruce D. Haynes (Boulder: Westview Press, 2011).

6 See: John Lie, Multiethnic Japan (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2001); Noah Y. McCormack, Japan's outcaste abolition: the struggle for national inclusion and the making of the modern state (Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2012); George A. De Vos, Japan's outcasts (London: Minority Rights Group, 1971).

7 Rositsa Mutafchieva, From subnational to micronational Buraku communities and transformations in identity in modern and contemporary Japan (Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada, 2011).

8 Masakazu Shirasawa. "Living Conditions of the Elderly in Buraku Ghettos in Osaka-city," Journal of Minority Aging 10, 1 (1985): 57.

9 Mutafchieva.

10 Wacquant, 26.

11 Shirasawa, 58.

12 Herbert L. Kessler and David Nirenberg, Judaism and Christian Art: Aesthetic Anxieties from the Catacombs to Colonialism (Phipadeplhia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 233.

13 Wacquant, 7.

14 Viorel Mionel. "Urban Ghettos and Electoral Elections. Why are ghettos important for politicians?", Sphere of Politics 5, 171 (2012a): 50.

15 Viorel Mionel. "Romania's urban ghettos - the preferred space of concentration of social welfare recipients", Revista de Economia Socială 2, 4 (2012b): 3-4.

16 The list of ghettos present in the analysis is far from exhaustive. It only reflects the examples that we had access to as a result of the available data and their theoretical identification with the models presented in the previous section, models that gave the start to the theorization of segregation and ghettoization processes.

Bibliography

De Vos, George A. Japan's outcasts. London: Minority Rights Group, 1971.

Kessler, Herbert L. and Nirenberg, David. Judaism and Christian Art: Aesthetic Anxieties from the Catacombs to Colonialism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

Lie, John. Multiethnic Japan. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Masse y, Douglas S. and Nancy, Denton A. Nancy. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1993.

McCormack, Noah Y. Japan's outcaste abolition: the struggle for national inclusion and the making of the modern state. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2012.

Mionel, Viorel. "Urban ghettos and electoral elections. Why are ghettos important for politicians?", Sfera Politicii 5, 171 (2012a): 50-58.

Mionel, Viorel. "Romania's urban ghettos - the preferred space of concentration of social welfare recipients", Revista de Economia Socială 2, 4 (2012b): 2-31.

Mionel, Viorel. România ghetourilor urbane. The vicious space of marginalization, poverty and stigma. București: Pro Universitaria, 2013.

Mutafchieva, Rositsa. From subnational to micronational Buraku communities and transformations in identity in modern and contemporary Japan. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada, 2011.

Sabău, Angela. "CRAICA - More than a ghetto, a way of life!", Informația Zilei, October 3, 2011.

Shirasawa, Masakazu. "Living Conditions of the Elderly in Buraku Ghettos in Osaka-city", Journal of Minority Aging 10, 1 (1985): 57-76.

Very, Ryan. "Black Capitalism: An Economic Program for the Black American Ghetto," International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 2, 22 (2012): 53-63.

Wacquant, Loïc. "A Janus-Faced Institution of Ethnoracial Closure: A Sociological Specification of the Ghetto." In The Ghetto: Contemporary Global Issues and Controversies, edited by Ray Hutchison and Bruce D. Haynes, 1-31. Boulder: Westview Press, 2011.

Ward, David. Poverty, Ethnicity and the American City, 1840-1925: Changing Conceptions of the Slum and the Ghetto. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1989.

Wilson, William J. When work disappears: the world of the new urban poor. New York: Knopf, 1996.