Notes on "neighborhood"

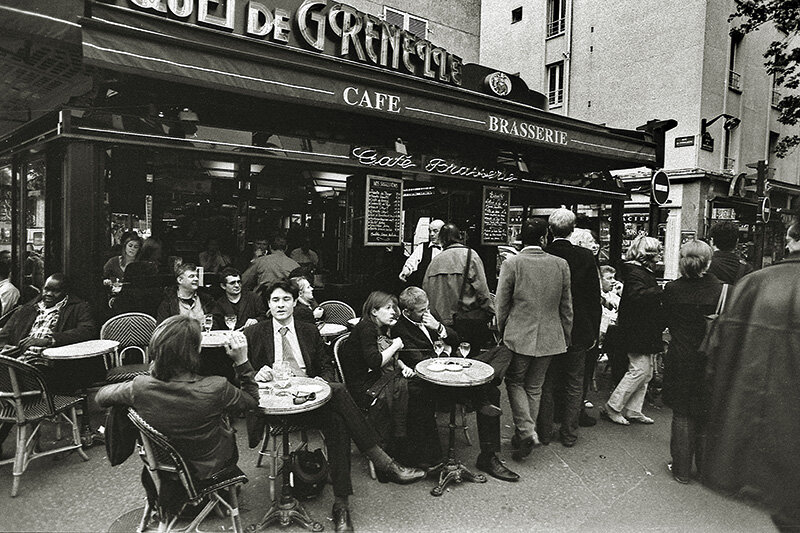

We use the word 'neighborhood' without dwelling on its deeper meaning, its charge. However, the notion of neighbourhood plays an essential role in the spatial organization and development of cities. In an attempt to define the term, we can say that neighborhood also means closeness, ambience, situation and proximity.

Neighborhood is linked to territory and it is what shapes the tension between occupation and conditioning. In other words, occupation is a relation of existence, and the conditioning of the occupation of the territory, of the land in general, is a matter of motivation. Neighbourliness is therefore an instrument of connectivity and of the coherence that is deduced from it in the organization of space: architectural, urban, territorial.

The unit of neighbourhood has been the instrument of spatial organization that has often said more than it intended to express, generating both good and sometimes bad states in the architectural-urbanistic composition of human existence.

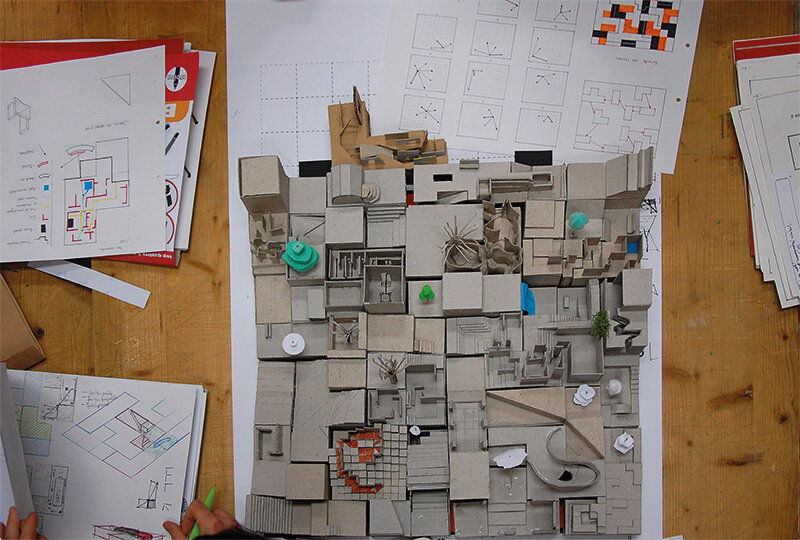

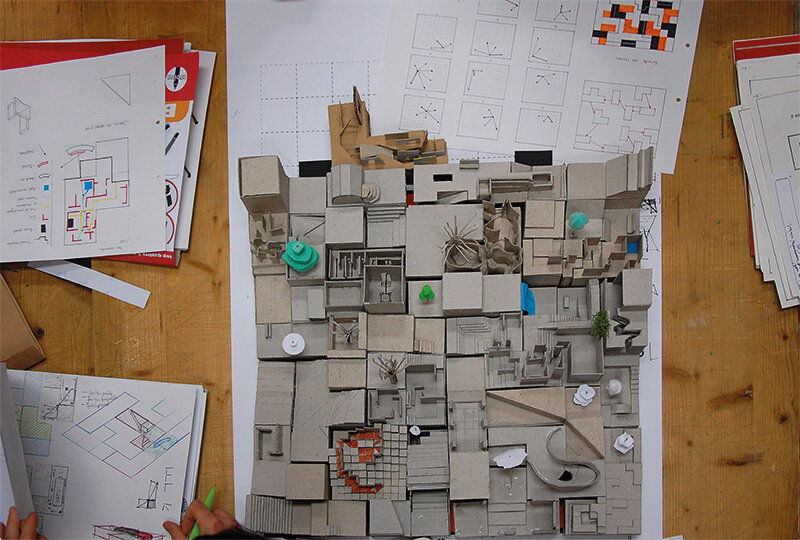

There is no architectural intervention outside the neighborhood because the architecturally defined space is always situated between something and something else. For example, between plots or lots, between one building and another, between one element and another, between basement and ground and so on.

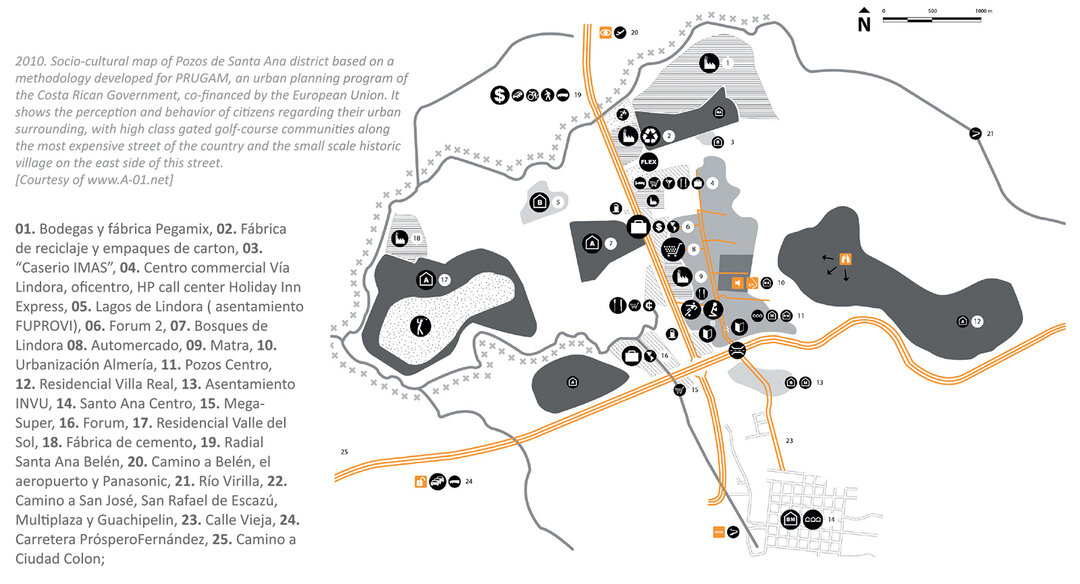

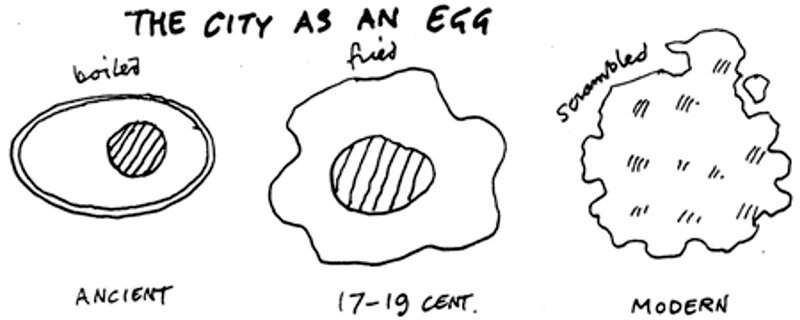

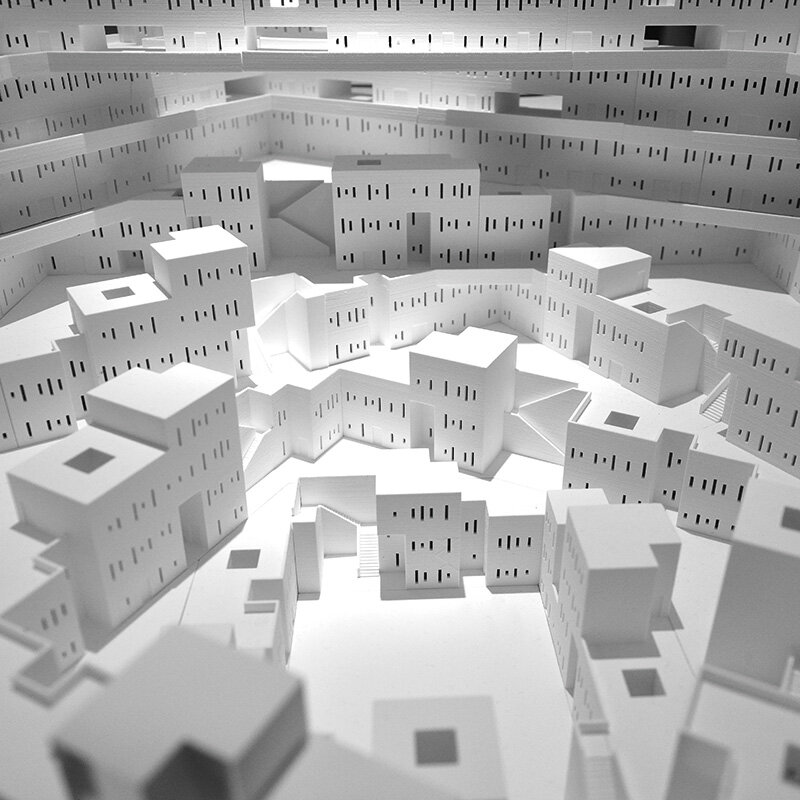

Neighborhood is an environmental relationship. But neighborhood is not simply the relationship between lots or between buildings. It implies a systemic understanding based on different scales of territorialization. The degrees of neighborhood range from individual/family/household/ensemble/town, and the notion of neighborhood is textualized differently depending on the scale at which this relationship is established. Society has developed along with the relational means of these different scales. Along with it, the neighborhood becomes more and more complex, requiring ways of approaching the whole.

Looking at the fields of urban planning and architecture and making an argument to the theme of this issue of Arhitectura magazine dedicated to the architecture of the city and the neighborhood, it is interesting to note that, in fact, the neighborhood states do not change; the approach changes, however, with consequences in terms of the effects of functionality, comfort, image, management.

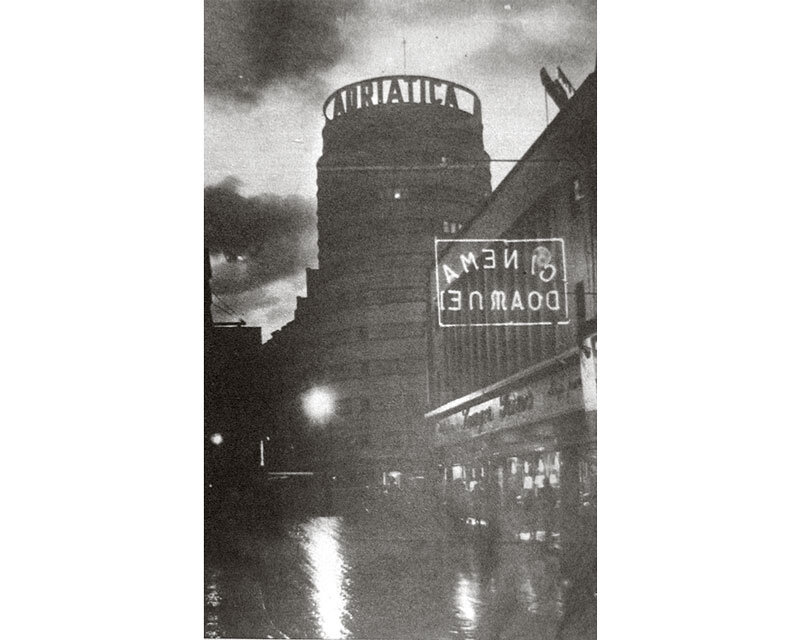

The functionalist model promotes isolation, in the sense of functional zoning within a settlement, neighborhood being not accepted as a relational state. But in the case of modernism (and if we refer to Le Corbusier, it cannot be said that the plan voisin denies the environment), surprisingly or not, situations arise in which the awareness of the primary neighborhood is put into operation: architectural space is in direct relation with nature. In the case of Frank Lloyd Wright and his organic architecture, the relationship between building and environment or between buildings is based on a devout submission of the architectural object to the nature or context in which it is inserted. At Richard Neutra there is a fluidity of indoor-outdoor space, and nature or the setting is an integral part of the built space, the living room of a house here being more than open, being made up with and of outdoor-indoor. Kisho Kurokawa interprets the neighborhood primarily in relation to the entrance. I remember with great pleasure the lecture he gave at the Ion Mincu Institute of Architecture in Bucharest in 1976. At that time, the Japanese architect said that one of the most important design gestures concerns the entrance to a house, where there must be something defined as a space belonging simultaneously to the interior and the exterior. The architect and theorist Cristian Norbeg-Schultz puts the genius loci philosophy through a multi-criterial detailing that emphasizes the depth of the relationship between two A-B elements in the environment. Through differentiation, the culturalist model assumes a creation of space that does not exist outside the neighborhood. An example in the continuation of this idea is the attitude of the architect Daniel Libskind who resorts to a recreation of the context. The creative procedure involves a kind of constructive forcing of a neighborhood thus able to favorably influence the architectural intervention. Neighborliness does not necessarily mean, in the sense of overall unity, indentity of elements/neighborhoods. A work of art can be made out of parts that are different in themselves, even contradictory; and there are urban layouts that are specific to precisely such a situation: Bucharest, for example. This should be understood as a natural manifestation of neighborhood in the compositional plan of intervention in urban restructuring.

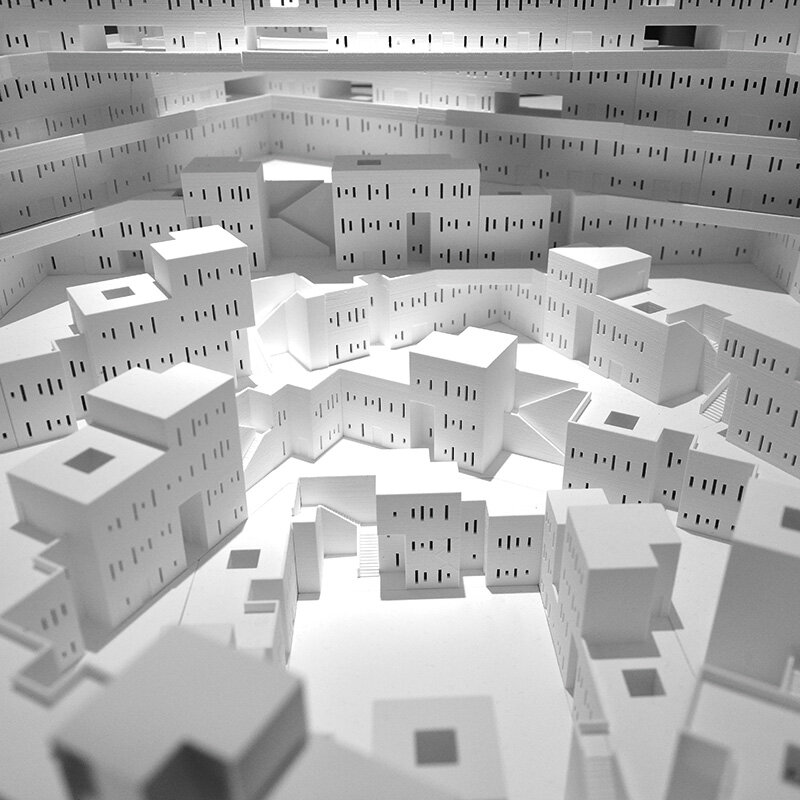

In conclusion, neighborhood is the essence of the composition from an architectural part up to the scale of spatial planning, and everything that an architect thinks is based on neighborhood. A building as a volumetric whole establishes neighborhood relations between forms. When creating a facade, neighborhood relations are established between voids and fullness, between morphological and obviously decorative elements. The architectural and urban scale, the principles of composition and proportions are, in fact, elements of neighborhood and the arrangement of things in pursuit of a happy result.

I would like to mention one essential, special thing, namely that the neighborhood is simultaneously aggression and taming. These two contradictory parts include the polar interest of the intervention and the particularity of the context. The unity of an ensemble is achieved through contrast. Urban composition aims precisely to tame the context in a superior way. In this way it is possible to emphasize in a created context that the dominant is something other than a vertically developed element. Through a deeply systemic understanding of the neighborhood and its territorial scales, it is possible to create a dominance of an ensemble other than the tower.

And if in a given context and at a given time the neighborhood does not contain a state of well-being, it is necessary to understand, realize and practice the neighborhood PACT. To be civilized and to acquire a state of comfort (architectural, urban or social) basically means understanding and respecting a sum of conditions between you and the surrounding space. In space, the place itself does not exist outside the neighborhood.