Tetrapolis

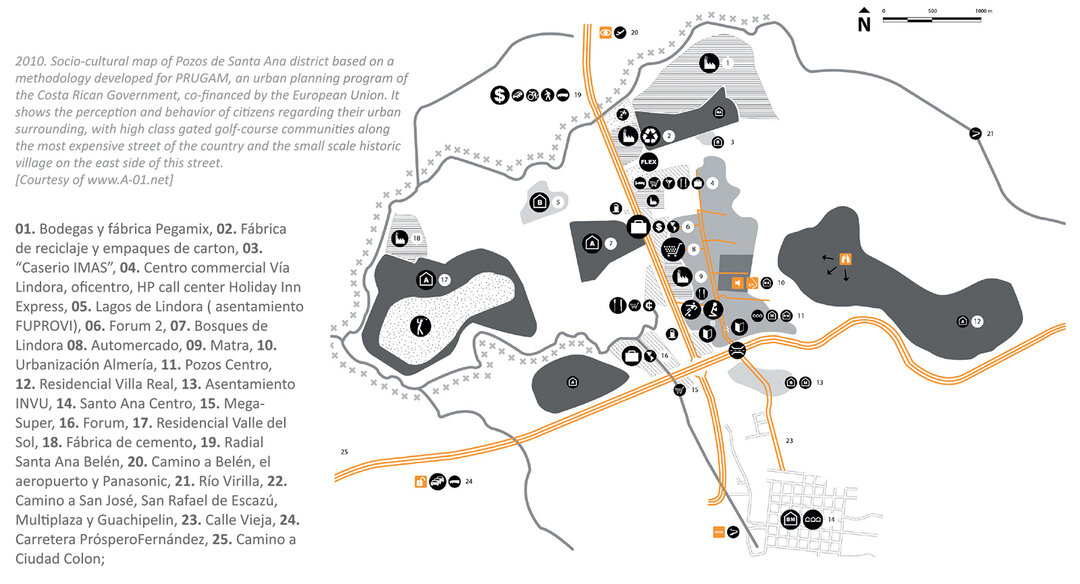

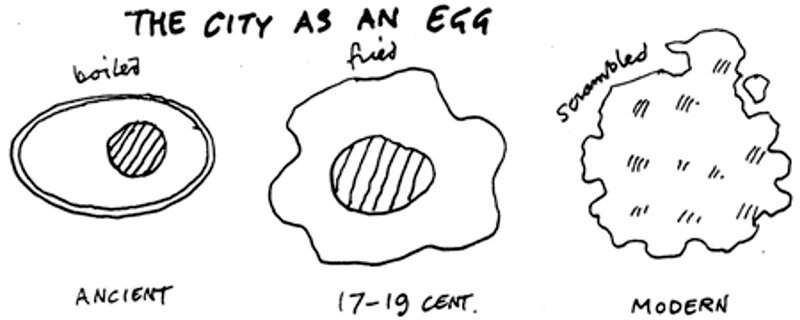

What does good neighborliness mean today? The simple attempt to define neighborhood in the hyper-theoretical context of post-modernity could take up pages of text, endless cultural considerations, structural, urban, philological, economic analyses... Without repeating this exhaustive exercise of reviewing all the meanings of neighborhood, I will start from a simple premise. Despite its semantic deconstruction, the neighborhood unit is still important. It is enough to look at the built space of contemporary, post-socialist and post-modern (as in modernity) Romania to observe the effects that the weakness of neighborhood units that are too little historically delineated has had in the relief of the topography of the present. Urbanism and architecture are written today, whether we are talking about elitist constructions or consumer products, as the sum of insular heterotopias. As a space of contact, but also of exchange, between these multiple realities, the neighborhood becomes a vague concept, difficult to define, precisely because it captures in its logic the dissolution of the solid, standardized structures in which, until recently, architects positioned their products. If we look at it through the speculative filter of game theory, the neighbourhood that harmonizes or hierarchizes the entities brought into contact appears to be the result of a complex game whose mechanics capture both the general conditioning of society and the altruistic or, on the contrary, selfish impulses of the players involved. How can we still "teach", how can we still explain good neighborliness to future architects in the context of this complexity?

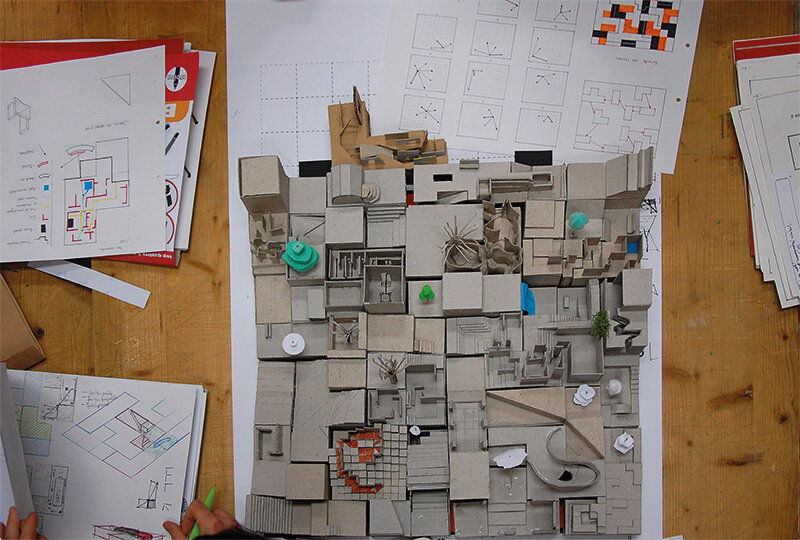

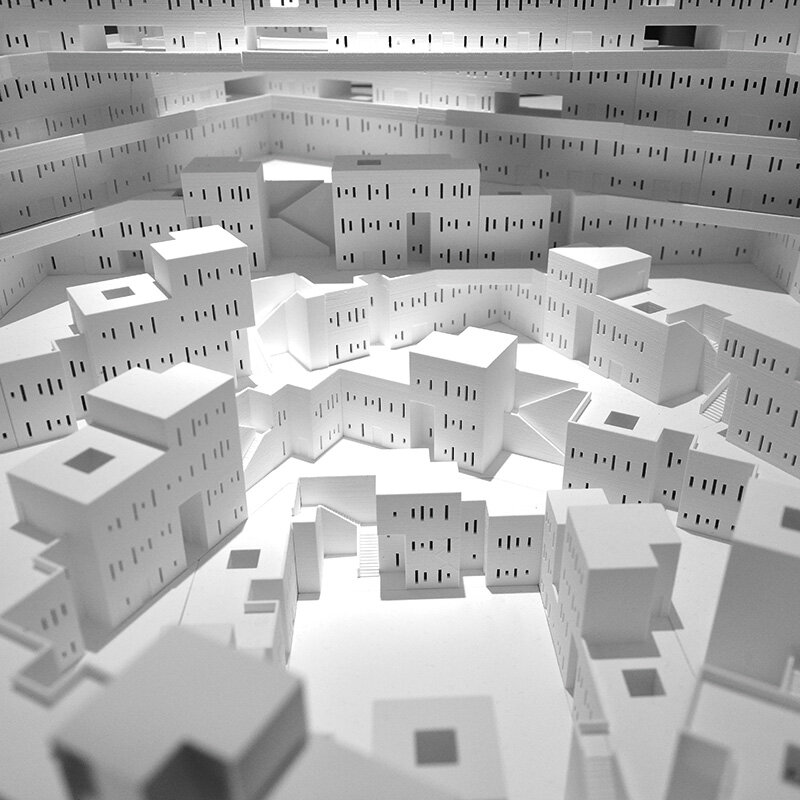

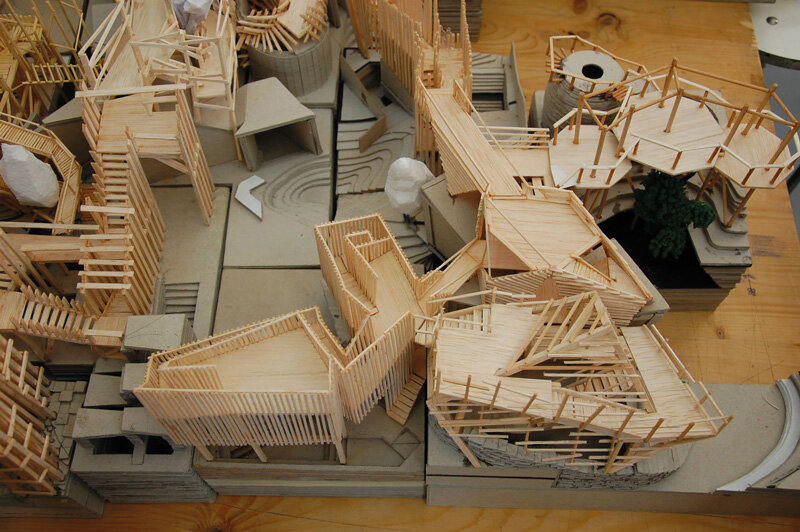

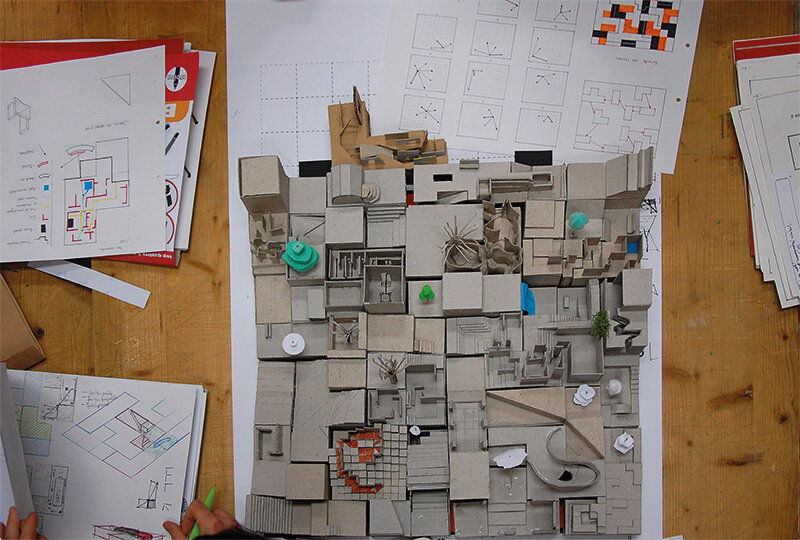

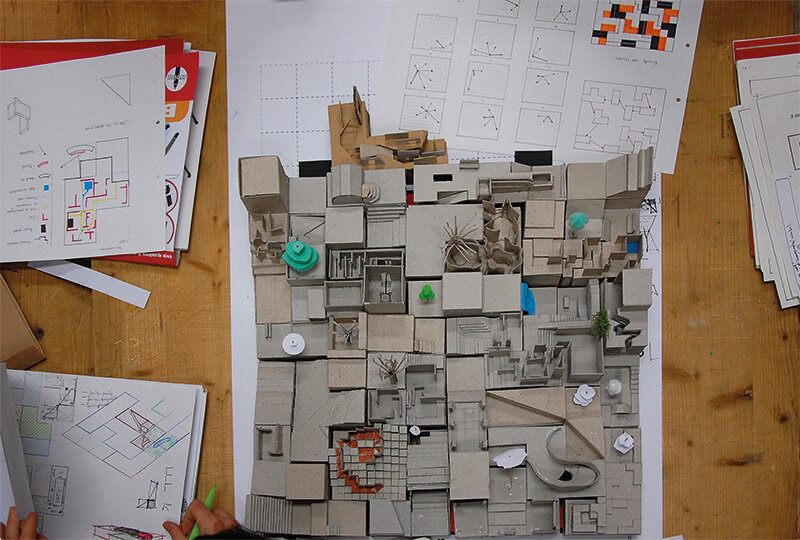

This is the premise of the experimental exercise designed for first-year students of the Faculty of Architecture in Timișoara. Following the logic of these relationships, the exercise tries to explain the neighborhood, proposing in turn a game built around the relationship between public space / semi-public space / private space. The four groups of the year are put in front of a green field game board, the final, constructed outcome of which depends to a large extent on the ability of the members of these groups to cooperate, to find a balance between the egoism specific to a certain extent to the creative process and the altruism necessary for cooperation. By encouraging both individualism and cooperation, the exercise has an important pedagogical component, simulating for the first time the problems of a participatory project. Not being theoretically contaminated by in-depth studies of urban planning or city history, the students are thus forced to operate intuitively, according to their predispositions or the cultural and social baggage with which they entered school. Good neighborliness is therefore not normatively conditioned, as long as it is the result of the multiple processes of negotiation needed to achieve individual or shared objectives. From this point of view, the results are not appreciated aesthetically, but processually. The process becomes as important as the result. It is also the reason why students do not work to achieve that final, 'liberating' moment of handing in drawings and models. Rather, they operate distributed across multiple study layouts and drawings collected in a study notebook that is meant to mirror the stages of this process. In this sense, the corrections are more often than not carried out in conjunction with the city built in its various stages. The neighborhoods thus condition both the individual solutions and the final appearance of the city. For a better understanding of the method I reproduce below some of the requirements of the theme. The full text can be found here: http://arhitectura1tm.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/layout-tema1.pdf.

The city is made up of multiple spatial sequences, passages, directions of movement (horizontal, vertical, ascending, descending), points of view, zones of respite. All are negotiated through the basic relationship of determination that exists between public and private space. For three months, Tetrapolis will be the virtual city where you will live with your colleagues. As a community space, a physical and intellectual construct, its success and competitiveness depend on how it is constantly shaped, presented and argued. In this city, as in any city for that matter, there are two kinds of forces, horizontal and vertical. The horizontal ones are the consequence of the dialog between citizens, of your ability to negotiate, to define the space for the common good of all. Where the dialog is weak, the arguments are equally weak and the community will not resist vertical forces. These will be exerted by us, the legislators of this space. Our behavior can therefore be despotic, if your community is weak, or, on the contrary, democratic, if we find in you a partner for dialogue. These are relations of balance and power relations that will be established over time, over the course of the exercise. (...)

Read the full text in the double issue 4-5 / 2014 of Arhitectura magazine

photo: Cristian BLIDARIU