About Block House

The magazine ARHITECTURA in partnership with the Romanian Radio Broadcasting Society continues the series ARHITECȚI LA RADIO with the manuscript of the radio program: Mircea Max Popovici, Casa Bloc (1934)

No area of social life underwent such important and numerous changes due to the war as housing. All the other institutions that suffered from the great cataclysm have been rebuilt and transformed little by little, only housing still finds itself in such a precarious situation after almost 20 years of prefactions.

All the other sectors, especially the industrial ones, have responded to the new problems imposed by the times, and have even found the necessary mechanisms to solve them. They have almost entirely overcome the difficulties created in our age by the so-called rupture between the present and earlier periods.

The whole working machinery of mankind, which for centuries has undergone nothing but slow transformations, has, in recent decades, changed with a speed as out of a fairy-tale.

For ten centuries, man has directed his own life and work, being himself the master of tomorrow; family life has therefore been the normal course. When the family is thus satisfied, society is also stable and therefore able to withstand the dangers that have constantly beset it throughout the ages.

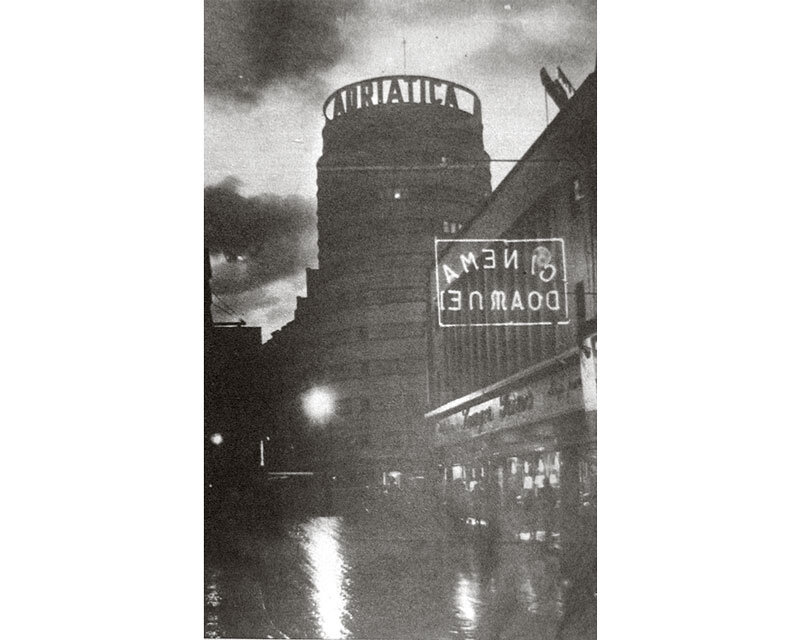

Today the mechanics of the family have changed. The formidable new industry that has sprung up is daily tempting us, whether through newspapers, magazines, motion pictures or radio, with an endless series of new objects that are being introduced into our lives, objects that both delight and disturb us, causing a restlessness that ends up by creating a new modern state of mind, corresponding to the modern objects and systems that concern us. To this new state of mind has contributed, and still contributes, to an extremely large extent, the ease of traveling long distances in a short time; a state of mind which provides us with many modern means of locomotion and which enables us to examine at our leisure the complex of the efforts of modern industry so lavishly sown over the whole continent.

And so everywhere we see nothing but machines which serve to improve the common life; and in our work outside our homes, in most hours of our life today, in factories, offices, banks, and other places where we work, we are constantly impressed by the great and useful contribution which these machines make to the comfort of the common life.

And then our eyes turn with nostalgia to the things that surround us in our old-fashioned interiors, and with much sadness to the great lack of comfort these interiors give us, finding our family life in this way bad and backward.

That is why the instinct in each one of us sometimes unconsciously, but very often consciously, formulates new desires which inevitably relate to family life.

For every man today knows that he needs sunshine, warmth, fresh air, hot water and clean floors; and accustomed to the ideas of hygiene and to the demands of modern comfort in all its manifestations, he no longer tolerates the rudimentary life of his predecessors.

The great industrial boom, with all its machinery, has created a huge class of intellectuals who toil with despair at the making of these life-improving machines, which they cannot profit by. The modern age presents itself to them as a great glittering show-off, but from the other side of the barricade. And then in their privacy they stand in dismay at the rudimentary way in which they live; and their thoughts claim rights over the machines that are put to the service of the home and should belong to all. The result is a great disharmony between the modern spirit, which desires to live in the rhythm and accord of the modern objects and systems that surround us, and the impossibility of being satisfied yet. Out of the struggle which civilized man undertakes to appropriate these things and systems to satisfy the modern spirit, and in the intimate life of his family, the need has arisen for an urgent and complete solution of these tendencies.

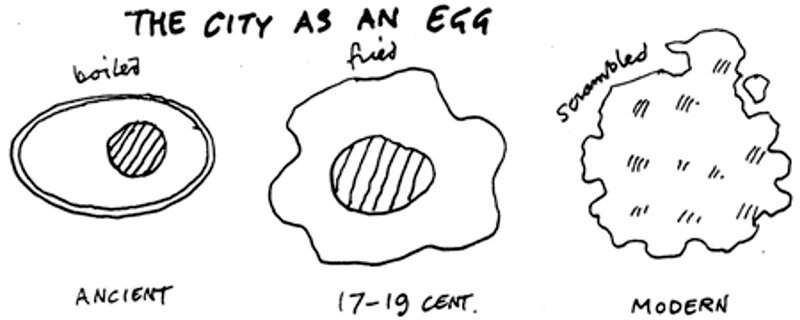

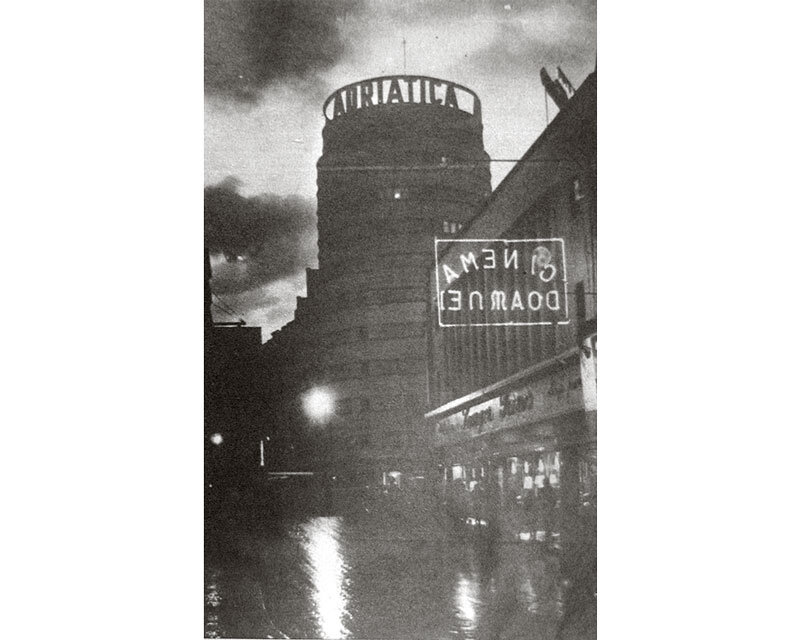

The housing shortage which has asserted itself so strongly since the war is to a large extent justified by these pressing tendencies. That is why, of all the solutions adopted for the solution of housing, apart from the villa or the so-called "cité jardin", the block-house solution has found an almost common use in almost all the large agglomerations of European centers. This is chiefly because it puts at the disposal of the co-owners, by safe and relatively low-cost means, the whole range of machinery which modern industry has made available to modern building, to satisfy the most exacting and complicated requirements of comfort and hygiene.

But, of course, it is also for the reason that the block-house system of building in storeys (the block-house), although located in the very heart of a city, brings down the price of apartments considerably, by economizing on land, foundations, exterior walls, roofing and common parts, and by the improved building processes which can be applied to such types of work.

If we look at the attempts that have been made lately in the various large cities of Europe, we see that in London in 1870, without any special preparation or thorough organization, and solely on private initiative, several series of such block-houses with several apartments for officials or factory workers were built without any special preparation or thorough organization. The results were also poor due to the lack of a serious organization and in particular to the outdated technology of those times, and the houses built soon became insalubrious centres, causing epidemics and tuberculosis. They were designed on narrow streets, without sufficient open spaces, and therefore deprived of the two most important and absolutely necessary elements of communal life: air and light.

However, this unfortunate beginning compromised the whole system from the start and prompted the intervention of the State and the City Council in the hope of solving the problem of shared housing for the better. This led to the idea of "garden cities" and in a few years companies were formed with the money of the owners of large industries, with the land made available by the town halls and with a wise organization, and the first garden city was built around 1890.

An ideal solution, but extremely costly and difficult to achieve even in better times and in rich and well-organized countries like England. England's example was imitated by Germany, which was in the same flourishing situation. Also with the help of the great owners of large industries, garden cities were built all over the country, the most important of which is Hellerau, near Dresden. The examples of England and Germany were later imitated by Holland, France and Russia, but only in the very rich and industrially well endowed regions.

However, since the solution of garden cities required enormous expense and great difficulties of realization, and since even if it had been solved it did not fully meet the multiple demands of modern life, it was soon abandoned and after the war was only revived in isolated places, on a small scale and more as a trial experiment. This led to a return to the idea of block-houses, a solution that would be more appropriate and easier to solve in view of the many financial and economic difficulties that mankind is experiencing today.

This building system has recently been solved by three methods. The initiative of the state, combined with the help of the town halls of the cities where these block-houses were being built, as in Vienna.

In Vienna, the city council took on the task of constructing the housing jointly, and the state the task of financing it. About 40,000 housing units (apartments) were built on entire streets and neighborhoods. In Munich, the private initiative system was inaugurated with the help of the city hall, while in Berlin the private initiative system was set up in the form of owners' associations, which built several blocks of flats in various parts of Berlin. After the war, however, these associations were dissolved in Berlin for economic and political reasons, and the problem of this type of housing was solved by private initiatives. The results were very bad; more than half of the buildings built remained unoccupied.

In France, the system of owners' associations, with the help of town halls or the state, has yielded good results whenever it has been successful. In Russia, in Petrograd, as in our country, it was started on the initiative of a few large entrepreneurs who worked directly and alone with the isolated owners, realizing huge profits and expensive and poorly conditioned housing.

As a result of this bad experience, owners' associations were formed, which placed themselves under the authority of the city and built about 400 block-houses with 40-60 apartments each. Also in Moscow, large associations of wealthy merchants placed themselves under the authority of the city hall and set up companies with a capital of about 40,000,000 rubles. The owners wishing to build received from the City Hall guidelines, plans and regulations, and from the capital of the merchants' association, the necessary sums at low interest, long annuities and with a guarantee on the apartments they built.

As can be seen from this brief history of the construction of blocks of flats in the various countries of Europe, the only system that has given good and reliable results has been the system of associations of owners who wanted to build and live together and who placed themselves under the direction and authority of the town hall as the competent body interested in the realization of blocks of flats that were as comfortable, aesthetic and in keeping with the needs and physiognomy of the town in which they were built.

However, as no one makes use of the experience of another, even when this experience brings unfortunate results, we did not make use of the experiences made elsewhere when we started two years ago.

We have only started to realize this kind of construction through the initiative of a few great entrepreneurs, and under conditions which for the time being provide these entrepreneurs with important benefits, and later on the regret and bewilderment of the hasty buyers.

If private initiatives and the work of a few large entrepreneurs have in recent years been able to realize a number of fairly well conditioned houses for flats, then of course the same simple initiatives will not be able to solve the problem of shared housing with sufficient understanding in the block housing solution, in which the tenants become owners this time and not even simple tenants as in the case of houses for flats.

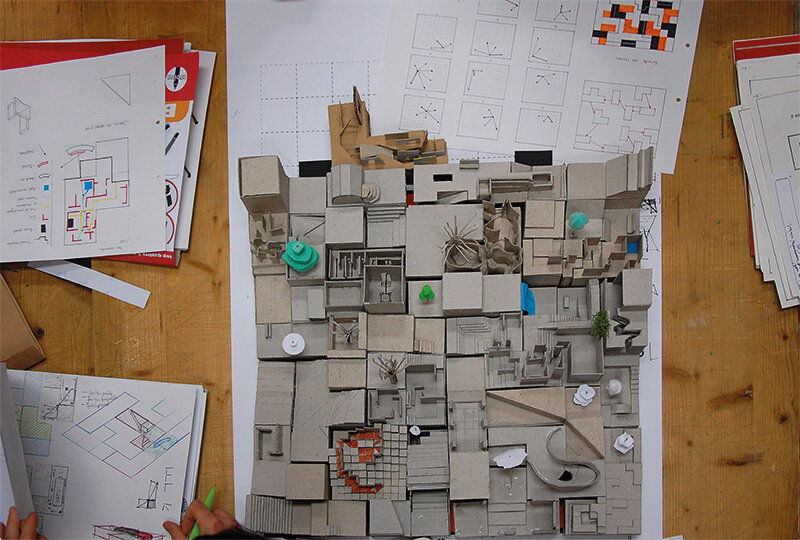

Since block-houses do not meet the economic need and their purpose unless they are located in the heart of the city center, this requires that they be as large as possible, with as many apartments as possible, in order to reduce the financial burden imposed on the building by the excessive cost of the land on which it is obliged to stand. This very factor gives rise to an infinite number of new problems for the realization of a good and convenient combination in such a building.

In addition to the establishment of secure legal relations between the builders and the future owners, and between the co-owners themselves, the plans and the nature of the elements which will make up the future buildings must first of all be carefully and skillfully examined. This is where the technical man and then the town hall must have their say, strictly regulating the future apartments in such a way that they have air and light and are protected from noise and unpleasant neighbors.

But once the plans have been approved and the work contracted, what and where is the guarantee that the work will be carried out according to the commitments signed, thus protecting the future owners from future inconveniences arising from poor execution or from the greed of greater benefits than those allowed?

Hence the need for associations of future owners to protect the common interests and to make buildings as comfortable and solid as possible, while complying with the specifications and rigorously executing the approved plans.

In general, contractors aim at the highest and surest returns, and do not invest their capital for random results. Owners who invest their capital in construction work that is not even carried out have no legal security. An action for repayment of the sums advanced or an action for damages presupposes perfect solvency on the part of the contractors, accompanied by certain contractual conditions. This applies in the event of non-performance.

But what about the execution of the construction in poor conditions and outside the approved plans and specifications? It is well known that certain construction defects which often occur after the works have been accepted can, in the case of apartment blocks, become capital defects which can destroy the peace of mind and contentment that a man should have in his own home. When, however, the plans are drawn up by the owners' association itself through its architects, who have only the interests of the members of the association in mind, and when speculation is no longer the main object, with the cooperative taking the place of private initiative, the block of flats will certainly take off.

With conscientious and capable technical people at their disposal to defend their interests vis-à-vis the contractors and the various authorities with which they come into contact in the construction and later in the management of these buildings, the owners' associations would be safe from the innumerable inconveniences arising from the fact of building and later of living in them.

As certain parts of the building remain in the joint ownership of the owners, such as the roof, staircases, installations up to the entrance to the apartments, attics, laundry rooms, the porter's room and the administration, all these parts must be given special attention during construction in order to avoid heavy maintenance or high repair costs later on. A whole set of provisions and a large amount of new knowledge, foreign to the new owners, enters into the execution and later the maintenance of the whole construction. Of course, only owners' associations flanked by specialized people can deal with so many new problems which often require urgent and well-thought-out solutions.

But since these associations cannot spring into being spontaneously, I think that certain associated technical people could, for the time being, make available to the general public, and especially to those interested, who are in most cases disoriented or ill-informed, consultancy offices where they could give information on the land, the plans that can be drawn up on that land, how it can be built and under what conditions, and also examine the proposed plans and the deeds of the land that is being purchased. In a word, well-organized offices which in due time will give the most reliable, honest and ample information.

As far as I know, seeing the need for such an office to operate in our capital, a handful of specialists took the initiative to set it up, obtaining the collaboration of distinguished technical and legal personalities.

Max Mircea Popovici, Casa bloc: Radio University broadcast, March 7, 8.45 p.m., S.R.R. Archives, file no. 6/1934, 8 files.

Mircea Max Popovici (1889-1966) studied architecture at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris (Paulin studio). Between July 6, 1917 and February 15, 1919 he directed the reconstruction works on the Mărășești-Nămoloasa front line within the framework of the Department for the Rebuilding of Regions after the War, rebuilding 21 villages, 900 households, repairing 1,800 households, 14 schools and two churches according to his designs. In 1921 he was the executing architect at the Neamului Cathedral in Alba Iulia, then, between 1922-1923, he worked at the Directorate of Urban Redevelopment - Ministry of Public Works. Between 1924-1950 he was a freelance, drawing up documentation projects and directing the execution of numerous state and private projects, he is listed in the 1926 list of architects.

Between 1919-1948 he designed and supervised the construction of 95 residential houses in Bucharest and the provinces, including 5 large blocks in Bucharest, 3 villas on the Prahova valley, a villa in Brasov and 15 villas in Bucharest. He took part in two competitions: Palatul Comunal București, winning the 2nd prize, and Palatul C.F.R.R. Between 1950-'53 he worked at IPC, in the Documentation Service, and between 1953-1966 at Radio and Television.

Here are some of the projects: 1: I. Moscovici - Mihai Eminescu street, ing. Gropper and Sucher - Radu Cristian street, eng. N. and I. Galea - Episcopiei street, eng. N. and I. Galea - Bd. Hristo Botev, eng. Stefan Popovici - Bd. Gh. Duca nr. 4; 2. Villas: painter Gheorghe Petrașcu house - 3 Zambaccian Museum Street, S. Sihleanu house - Paris Street, Dr. N. Dumitrescu villa - 54 Bitolia Street, Eng. Nestorescu - Calea Văcărești, house D. Manthel - str. Olteni, villa C. Danielescu - str. Viitorului and others. 3. Fitting out and renovation of the Radio Broadcasting Company's headquarters and creation of the first broadcasting studio, finishing for studios and studios for UKV stereophony, reverberation, music and voice recording.