Architecture and comfort

ARHITECTURA magazine in partnership with the Romanian Radio Broadcasting Society continues the series ARHITECȚI LA RADIO with the manuscript of Grigore Ionescu's radio program, Architecture and Comfort (1936)

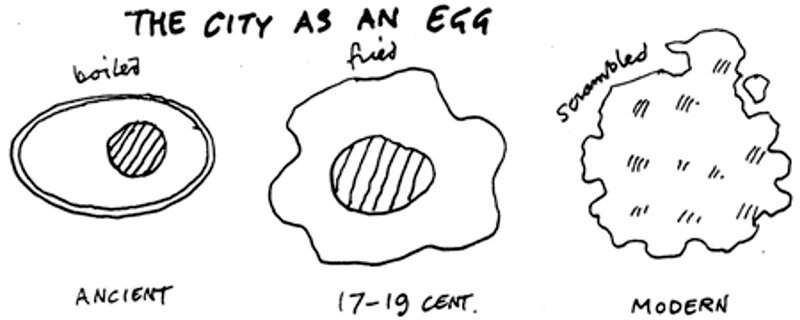

When the idea of the dwelling was born in the Neolithic era, the need that prompted man to build was exclusively that of shelter from the elements. The prehistoric dwelling, the role of the earliest construction, consisted of a single room of rather irregular shape, and was partly dug into the ground. But as the civilization of the people increased, so did their way of life. As a consequence, the plan of the primitive dwelling, rudimentary and utterly lacking in comfort, was modified and enlarged so as to meet the new and more and more refined requirements of life.

Leaving aside religious architecture, which forms a special chapter in the civilization of peoples, the dwelling-house is the building to which man's attention has always been primarily directed.

A dwelling may be either independent, for an individual or a family, as it was in the beginning, or it may be part of a block of flats, as we have found in some cases since the Renaissance, and very often today in all the world's large cities.

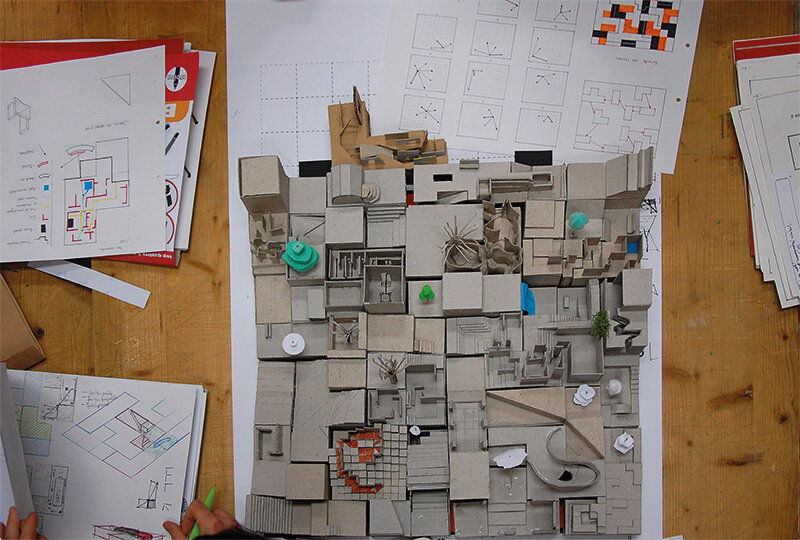

The essential thing in the composition of a plan of a dwelling lies in the grouping of the parts required by the program into a harmonious and practical whole, and in the completion of the parts with all the accessories capable of satisfying, in a smooth and perfect manner, the requirements of hygiene and comfort: bathrooms, running water, sewers, airing, heating, lighting.

Architecture is not, however, just about meeting these practical requirements. A building cannot be a work of architecture if it does not satisfy both reason and the eye. This cannot be achieved if the other elements which, like the practical, are an integral part of an architectural work, are neglected.

Let us explain: The practical element represents the positive requirements of the program, the very purpose of the building. It constitutes the raison d'être of the architectural composition. The technical element is the construction itself, which is the totality of the means by which the architectural composition can be realized; and the aesthetic element is the art of proportioning and embellishing the building, that is to say, the art of giving it expression both inside and outside.

Seen through the prism of these elements, architecture can be either monumental, i.e. created with the intention of highlighting a lofty idea, a superior conception, which is not linked to an immediate practical purpose, or utilitarian, i.e. architecture born of the need to satisfy a vital necessity.

From the point of view of the aesthetic element, we can distinguish two types of architecture in both monumental and utilitarian construction: volumetric or spatial and decorative. Volumetric architecture is the result of building masses which are chained or superimposed and which are capable, by their form and the relationship between them, of producing on the individual an architectural sensation, pleasant or disagreeable. Decorative architecture is intended to polish forms and adorn surfaces, that is to say, in a word, to cover an organism which from the material point of view is perfectly constituted.

Volumetric architecture, devoid of decoration, but presented in the form of a harmony of proportions and forms, that is to say, capable of producing a pleasing sensation on our visual sense, represents, according to the modern conception, the essential, the true architectural beauty.

But it was not until the twentieth century, however, that this beauty, represented in the form of emptiness, was appreciated in architecture. Moreover, to the extent that it was emphasized by modern architecture, it could not have existed any other time, because the forms of the new architecture are a consequence of the new building materials, reinforced concrete and iron.

By the end of the 19th century these materials, which were cheaper and more solid than brick and stone, were already known, but it was not until after the war that their use in construction became widespread. Those who first used them, however, were afraid of changing the appearance and the established rules of architecture, so they tried as far as possible to conceal their true character. Iron skeletons, meant to remain apparent, are loaded with unnecessary shapes and decorated lavishly, while reinforced concrete, hidden in the walls, borrows the forms of stone architecture. But there was not much further to go before forms were rationalized and all the benefits to be gained from the use of new building materials were brought to the fore. If reinforced concrete and iron were more economical, and their use gave superior solidity to construction, to hide these materials under a borrowed cloak was to violate the soundest principle on which the development of any architecture is based: honesty. The first of all the conditions which must be satisfied in order to find the forms of a new architecture, Viollet-le-Duc said as early as 1872, is that of not lying, either in the overall composition or in the smallest details of the building to be constructed.

The realization of modern construction in accordance with this sound principle was, however, at first hampered by tradition and especially by what are called in architecture styles. In some countries, however, where boldness has done away with tradition and the tyranny of styles, the rationalization of construction has yielded appreciable results. Little by little the example has been followed by other countries, and thanks to modern means of communication and the exchange of ideas, new architecture has spread with astonishing rapidity in a few years, becoming the dominant style in buildings of all kinds in Europe and on other continents.

The machine-building phenomenon, which led to a migration of the working masses to the cities, caused a housing shortage in the latter. The most burning issue on the agenda in connection with this phenomenon was, and still is today, the problem of construction. The predominant type of construction is the dwelling house. To build a dwelling means to provide a person with a number of rooms, the whole of which is capable of ensuring a pleasant, peaceful and comfortable life. The house must satisfy certain needs and fulfill certain functions. How, then, should a house plan be composed in order to meet the requirements of modern life?

We live, says Le Corbusier, under the domination of the machine. The most authentic and remarkable creations of our age are the products of the machine: the automobile, the airplane and the ship. If we are to be men of our time, the best thing we can do in building new constructions is to follow the example set by the machine, that is to say, to adapt all the parts which make up a whole to the whole, and to subordinate the means to the end.

Modern architecture calls for the elimination of unnecessary ornament, the limitation of the surface area of rooms to the necessary minimum, the reduction of building and maintenance costs, and the increase of comfort by the use of all the means which the discoveries of modern technology make available to us.

Let us now see to what extent these desires have been satisfied.

The construction on reinforced-concrete frames has first of all made it possible to bring as much light as possible into the interior. Light means health. Modern architecture is architecture of light. In brick or stone construction, the walls were meant to bear planks. Consequently, these walls had to be thick and, given their load-bearing function, the cutting of window openings was done with judicious economy. To ensure that the perforated wall provided as many and as strong a foothold as possible, the windows were narrow and always arranged vertically. In modern construction, floors are carried by concrete pillars. Walls are no more than auxiliary infill elements. In such circumstances the window can be placed on a whole wall between two pillars or, passing in front of the pillars, a whole window can, at will, wrap around the house like a light bellows. The long shape of windows in modern architecture responds to the need to bring in as much light as possible. A long window, cut into the wall from one end of a room to the other, gives more light than two vertical windows whose surface area equals the surface area of the long window. Photographic experiments have proved that the light in the first case impresses the photographic plate in four times as short a time as in the second, which means that such a window gives four times as much light.

If light brings health, it doesn't mean we should abuse it. A room that is battered by too much sun in the summer cannot be inhabited. The systemic curtain is not able to prevent the sun's heat from penetrating at all, and while the central heating system is capable of keeping the cold out in winter, air conditioning and double-wall neutralizing construction are still too expensive to be affordable for anyone.

As for the plan itself, the difficulty lies in sizing the various parts and arranging them in such a way that movement is smooth and rapid. It goes without saying that each part, being called upon to meet a particular need, must be dimensioned in relation to the function it is called upon to perform.

For reasons of economy, attempts of all kinds have been made in this direction, particularly in Germany, to establish the minimum acceptable surface area for rooms in which an individual can live comfortably, fulfilling certain functions: eating, sleeping, working.

The results have not always been satisfactory, for the good reason that the arrangement of an apartment plan with a series of rooms whose dimensions were strictly fixed in advance has led to solutions which are generally not very organic, not to mention the lack of proportion in some rooms.

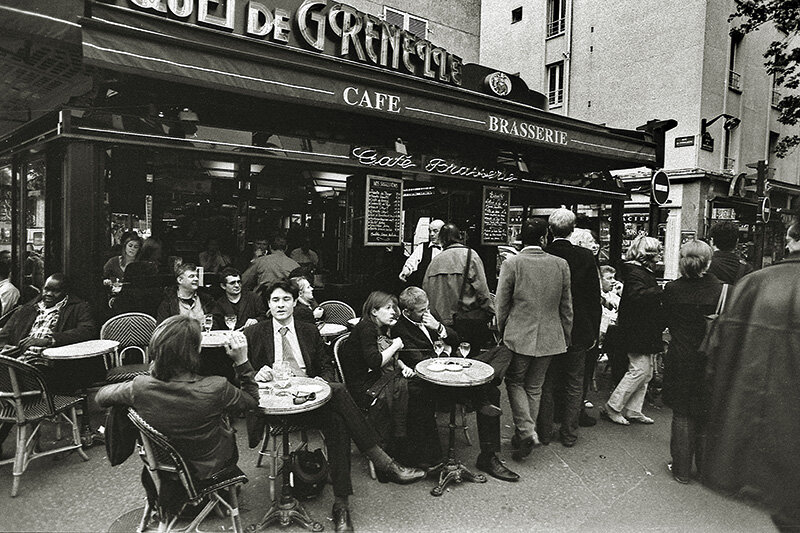

Economy in architecture should not be a goal. However precious it may be, it must not lead us to excessive floor plan solutions, to the delineation of rooms that condense our needs and reduce our every gesture to a limited amplitude. No matter how much machinism has become part of the spirit of the times, and no matter how deeply rooted the idea of the useful reduced to the strictly necessary has become, modern man has not entirely lost his sensitivity. On the contrary, spending most of his time out of doors, in factories, on the shop floor, or on building sites, where he struggles to earn a living by brutally struggling against all the ills of life, he expects, even demands, that his home should be comfortable, that it should be capable of providing him with spiritual relaxation, physical pleasure, joy, sensation.

Is the modern home capable of satisfying exactly these requirements? The answer may well be yes. The wealth of new building materials, the progress of science, and the discoveries of modern technology have provided architects with all the necessary means with which to realize this ideal of the modern dwelling.

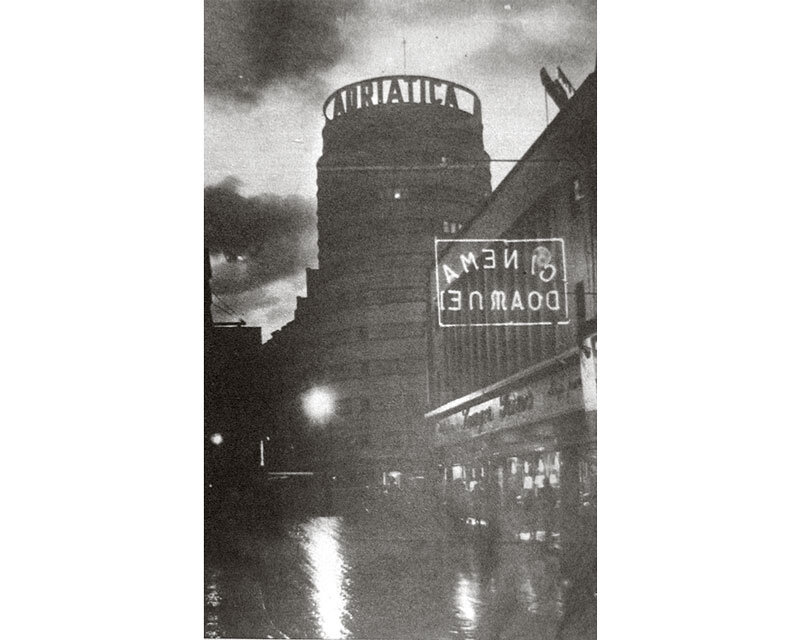

The apartment block, this ancient invention, the advantages of which have been realized and used on a very large scale only a few years ago, has made it possible even for those of less material means to enjoy the benefits of a comfortable dwelling.

The collective housing block saves land, reduces the cost of construction, lowers the cost of installations of all kinds, promotes comfort and also reduces maintenance costs.

In our country, modern architecture has become known and appreciated mainly through these blocks of collective housing. Unfortunately, however, not everything that has been built in Bucharest in this direction exactly meets the requirements of true modern architecture. I am not only talking about facades, about that spatial architecture, about which I said a few words at the beginning, but especially about interiors, about that whole complex of elements so important, through which architecture comes into direct contact with life.

The fault lies not so much with the isolated owner, whose education in architecture is not so complete as to enable him to understand everything that should and should not be done, nor with the architect, who in most cases is not the employee of the owner, whose interests he is supposed to defend, but rather with the capitalist who finances the construction, or the contractors, who, in collecting money from future co-owners, are primarily seeking to satisfy their own interest, which is profit. This gain is realized through economy, and if economy is excessive and misunderstood, it cannot, as we have seen, lead to satisfactory results.

Apart from the inadequate size of the rooms, the reduction of window areas, the restriction of light courts to the minimum permitted, which in the case of high and cramped blocks become simply 87 ventilation shafts, one of the greatest enemies that can arise in collective dwellings is noise. Reinforced concrete, in addition to other appreciable qualities, has the defect of being noisy, and if measures have not been taken from the outset to prevent this turbulent agent from penetrating the interior, the apartment may become uninhabitable.

The problem of noise in modern architecture is as important as the problem of light. A dwelling is not truly comfortable if it does not provide the occupant with perfect silence.

But it's not just the noise of your next-door neighbor that disturbs the peace and quiet of a home. From this point of view, the problem is much more serious, especially in Bucharest, where trams run on the biggest and most populated streets, where the shrill honking of cars is as loud during the day as at night, where the street hawker, as dawn breaks, haunts the streets shouting his precious merchandise for sale as loud as he can.

These shortcomings, however, cannot be removed for the moment without the help of the authorities. I say for the time being, because the problem of a dwelling capable of keeping out all undesirable agents has been solved in theory - in a modern palace in Moscow, in part, and in practice.

This hermetic house has double floors and walls built with neutralizing materials. The movable windows have been replaced with double fixed panels of special glass whose isothermal value is equal to that of the wall walls. The air inside is supplied by a mechanical ventilation system. This air, which is regularly circulated at a rate of 80 liters per minute per person, can be heated or cooled - depending on whether we are in winter or summer - to the desired temperature.

This house, in theory, is ideal, it removes noise, it removes draughts, it removes heaters, it removes dust.

Is this the house of tomorrow, the house which, in addition to the advantages mentioned above, can also become, if necessary, with slight changes of circumstance, a gas-proof shelter so precious in the event of chemical warfare!

The practical spirit of the future will be able to decide.

Grigore Ionescu, Architecture and Comfort, Radio University, August 7, 8.55 p.m., S.R.R. Archives, file no. 15/1936, 9 tabs.

Grigore Ionescu (1903-1992) architect - theoretician and practioner, professor emeritus, member of the Romanian Academy. He graduated from the Faculty of Architecture in 1931, continuing his studies in the following years as a scholar of the Romanian School in Rome. From 1935-1973 he was a lecturer, then professor at the Faculty of Architecture, being dean from 1944-1950.

His works include: 1. Toria TB Sanatorium, Transylvania (1934-1935), Bîrnova TB Sanatorium (1935), Nursing School at the Military Hospital, Bucharest (1936), Red Cross Sanatorium, Mangalia (1937), Vaslui Red Cross Sanitary Center (1937), Sighetul Marmației (1937), Huși (1937), Bîrsana, Petrova and Borșa (1938), Emilia Irza Hospital, Calea Lacul Tei (1950), Garajele autoambulanței, Bd. Averescu (1939). 2. The tramway depot in Bucureștii Noi (1942) - in collaboration with eng. Victor Popescu, the administrative building of the RATB depot, Bucureștii Noi (1949), the apartment block for RATB employees, Calea Lacul Tei (1949), the night sanatorium for RATB employees - Ștefan cel Mare depot, Bucharest (1951). 3.

But his major activity was in the field of architectural history and national heritage. He also had a rich activity in the field of conservation and restoration of historical monuments, being also the director of the Historical Monuments Directorate. He published numerous articles, lectures, conferences, but he is best known as the author of the history of Romanian architecture, the first work of its kind published in Romanian specialized literature.