Urban ruins in transformation

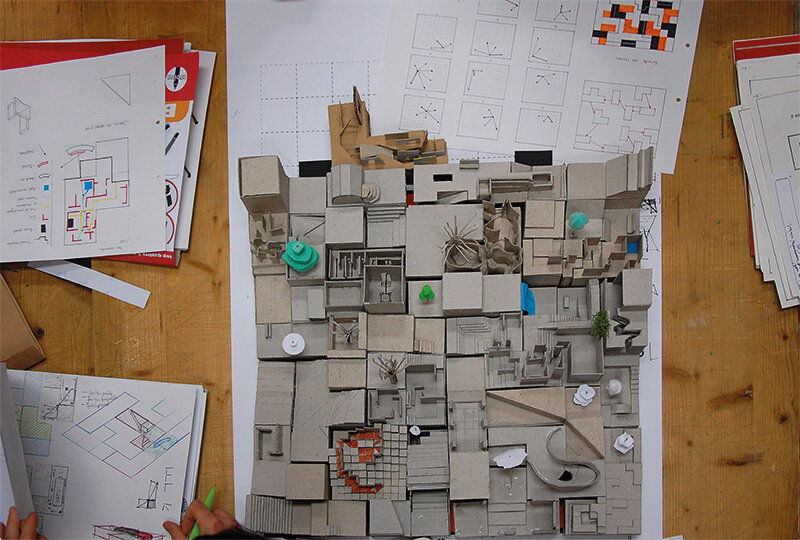

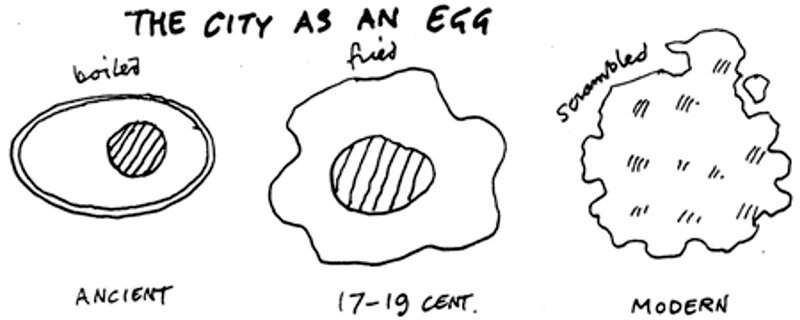

Wishing to briefly review some aspects of urban shrinkage noted on a recent visit to Detroit's fascinating, nearly emptied urban core, we open this theoretical discussion with an ironic but relevant caricature. Cedric Price's ovo-urban analogy of the early 1990s succinctly expresses the process of urban transformation: because they are not hermetic, closed, finished assemblages, cities change: they grow and contract, constantly and forever. The theme of urban transformation is not a new one - it is that of a continuous, ongoing process, the result of the interdependence between society and the city, articulated by needs, demands, interactions, forms of living/living.

The debate starts by arguing the place that the subject of shrinking (of urban decline and contraction) occupies in current discussions about an urbanity that is, paradoxically, constantly growing. The contemporary urban discourse is still preoccupied with urban polarization and urban density, a critical topic, which is emerging with different gaps and intensities in the United States, Western Europe and, more recently, Eastern Europe. As a reaction to the uncontrolled urban sprawl occurring in the above-mentioned places, on a different scale and with a significant time lag, various proponents of the compact city and the idea of smartgrowth have been emerging since the 1960s1. In Western Europe, such urban densification policies are relatively recent in the last 20 years, while the East is in its infancy. For the time being, these countries are trying to manage the sprawl that is emerging post 1990 in most Eastern European countries.

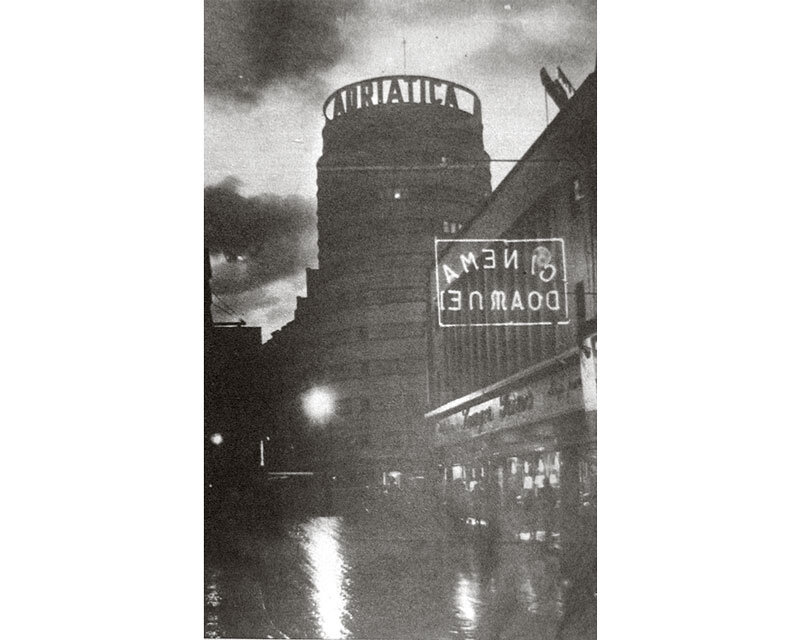

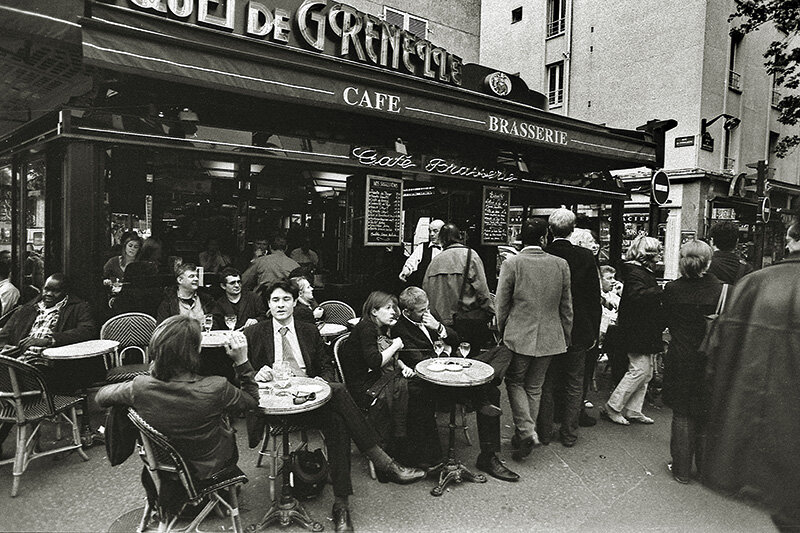

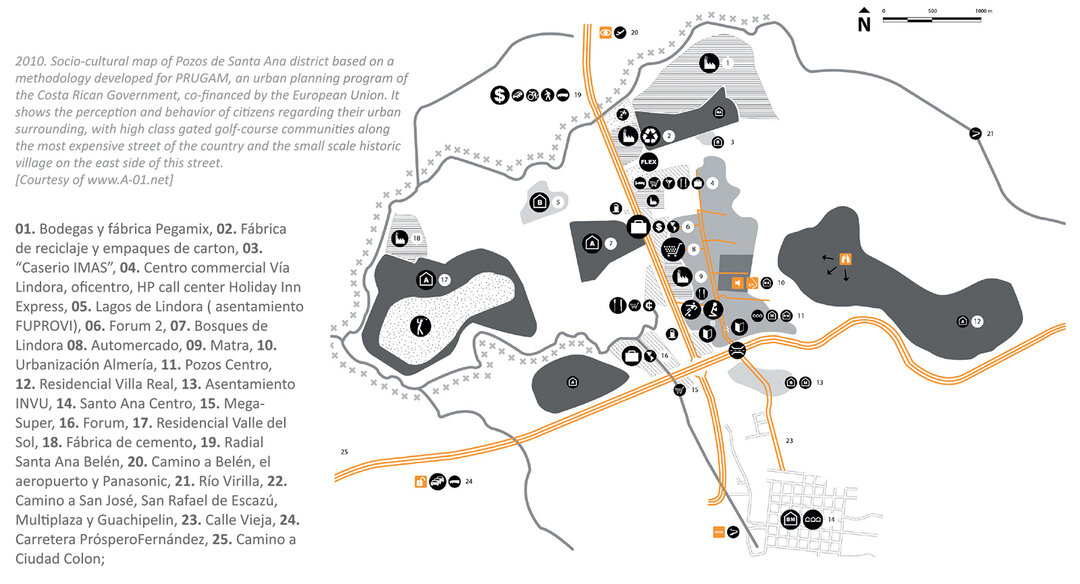

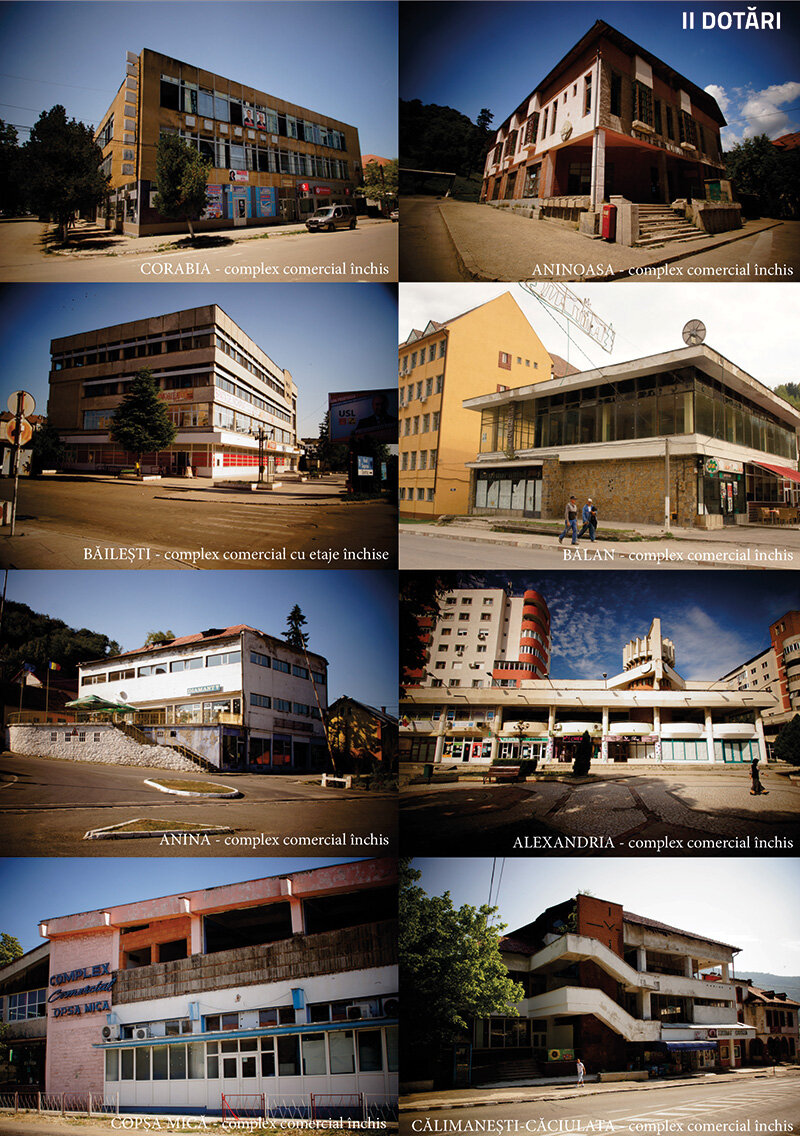

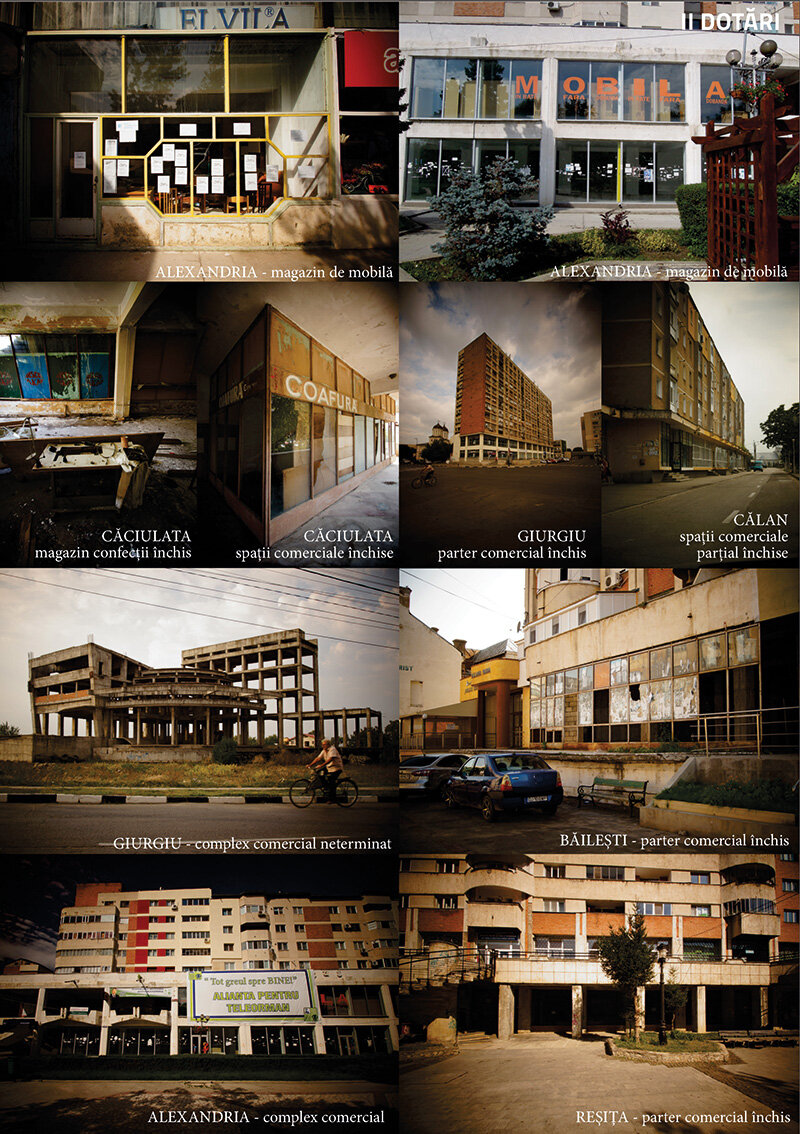

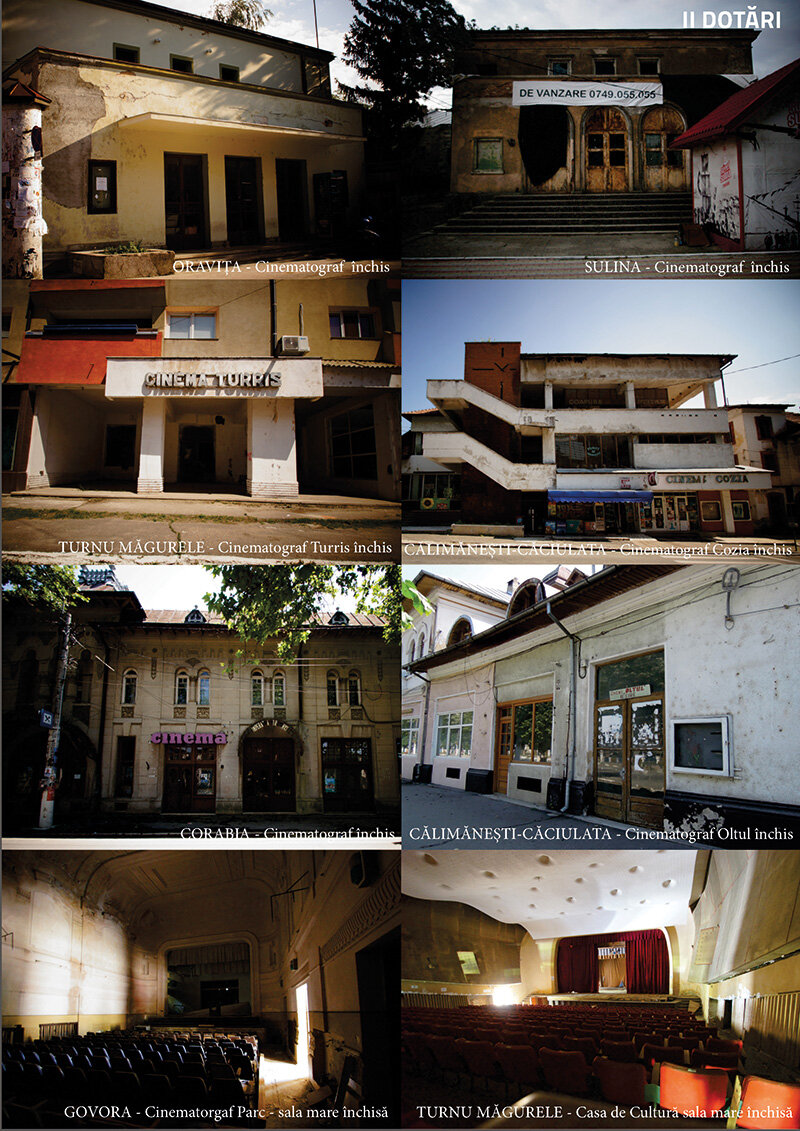

While in the West urban sprawl was already considered a malformation, Romania in the 1980s was preoccupied with densification in the name of efficiency, responsible for serious mutilation of the image of cities. Today, in a country with a shrinking population like Romania, the current urban sprawl(as a reaction to the enclosure and deprivation of property under communism), the very thing Western society tried to combat, seems senseless. In 1938, Wirth defined urbanity according to three criteria: size, density and diversity2 - so, according to him, certain very small, over-densified or mono-oriented forms of organization should not even be considered urban (characteristics that apply to many Romanian cities today). On the other hand, if shrinking cities designates a decrease in density, as shown by statistics - can this offer a desirable alternative, as has often been shown in history, out of a desire to decongest the center or as reactions to the compact and suffocating liberal city3? Today, the decentralization of post-industrial spaces is creating urban voids with enormous potential, which can serve other purposes than densification. Landscape urbanism is that interstitial discipline that operates outside the built environment, through which those terrains vagues (Robert Smithson), marginal spaces (Ignasi de Solà Morales Rubió) take on a different value.

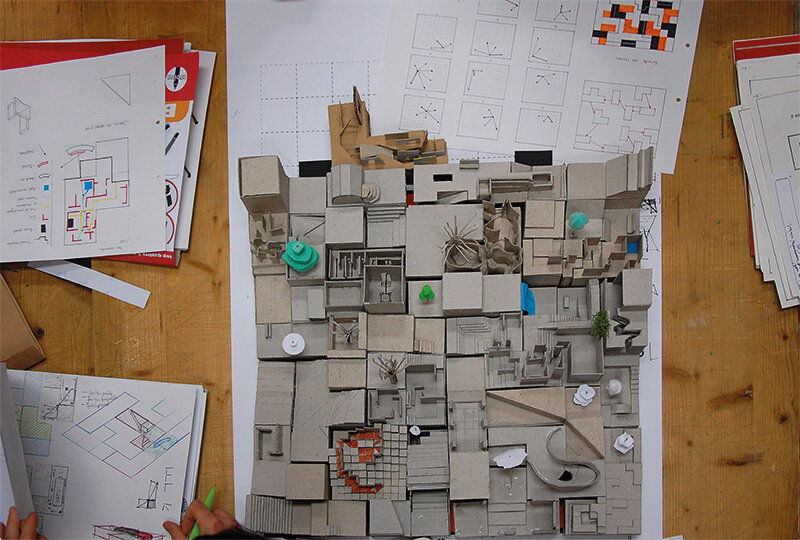

In any case, contemporary urbanity is dynamic and characterized by the coexistence of growing and shrinking areas, and the shrinking city discourse is an active part of it. With the help of Cedric Price, who compares the morphology of the city to an egg, we will retrace the sequences described above. The early image of the European city, of a compact city, is represented by the boiled egg - a metaphor for the medieval city, with a clearly distinct center and a well-defined outline providing a cohesive inner community. The industrial revolution and related urbanization, traffic flows break the clear contours and turn the city into a boiled egg, expanding its edges but maintaining a well-defined core. The modern city becomes an omelette: it loses its density, its compactness, it spreads out over the peripheries, the center dissipates. To extrapolate, contemporary urbanity would be a kind of hollow egg with gaps and permeable public-private, urban-rural, public-private boundaries. As a result of the expansion of the city, the geometry of the city's structure becomes fractal, unifying the city with the territory. So, this description is not only valid for the city itself, but can be extended to the territory, describing a metropolitan goblin-like4 fabric composed of different urban textures (some concentrated, some diffuse). Drawing an analogy with Price, Gunther Laux5 characterizes the contemporary urban as a "Kaiserschmarrn" with nuts and raisins (Franz Joseph of Austria's favorite egg pancake - a fragmented dessert, with both fluffy and crunchy pieces). (...) (...)

Read the full text in the double issue 4-5 / 2014 of Arhitectura Magazine

Notes:

1 This discourse goes as far back as the 1960s, to the fierce advocate of density as a source of diversity, Jane Jacobs.

2 In Urbanism as a Way of Life 1938; the observations take the post-World War I American urban world as their starting point.

3 The Garden City, Broadacre City, linear city forms, etc. It is true that these models were also created with urban growth in mind, but as low-density alternatives.

4 Castello defines it as "metropolitan tapestry" (Rethinking the Meaning of Place: Conceiving Place in Architecture-Urbanism: 97).

5 In Media and Urban Space: Understanding, Investigating and Approaching Mediacity, ed. Eckhardt p. 39.