"Void Deck"

Singapore - a former British colony and a trading hub on the border between East and West - is a busy intersection and an intense conglomerate of different cultures, religions and styles. It is a fast-growing country that in the last thirty years has doubled its population from two million to more than five million. Thanks to this explosive growth in relation to land scarcity, four out of every five Singaporeans live in collective housing.

The silhouettes of towers dominated by Marina Bay Sands and Gardens by the Bay are symbolic of a globalized environment and reflect the island nation's ambition to become a sustainable global city of the future.

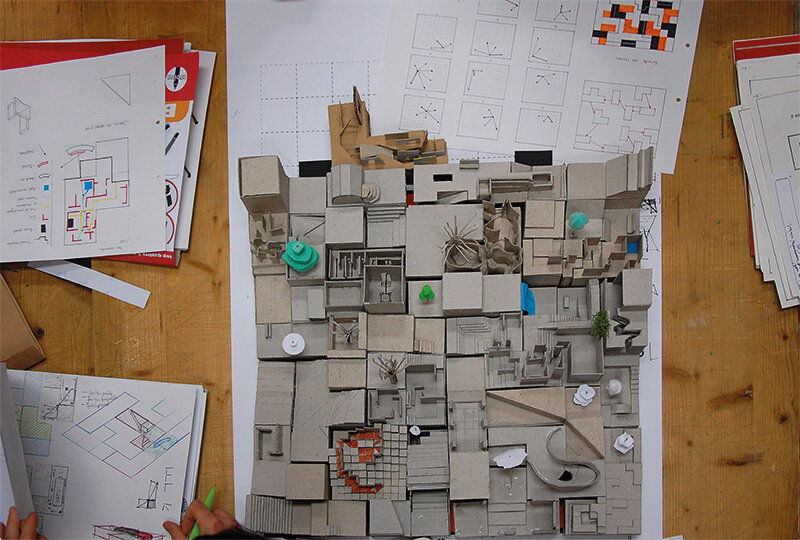

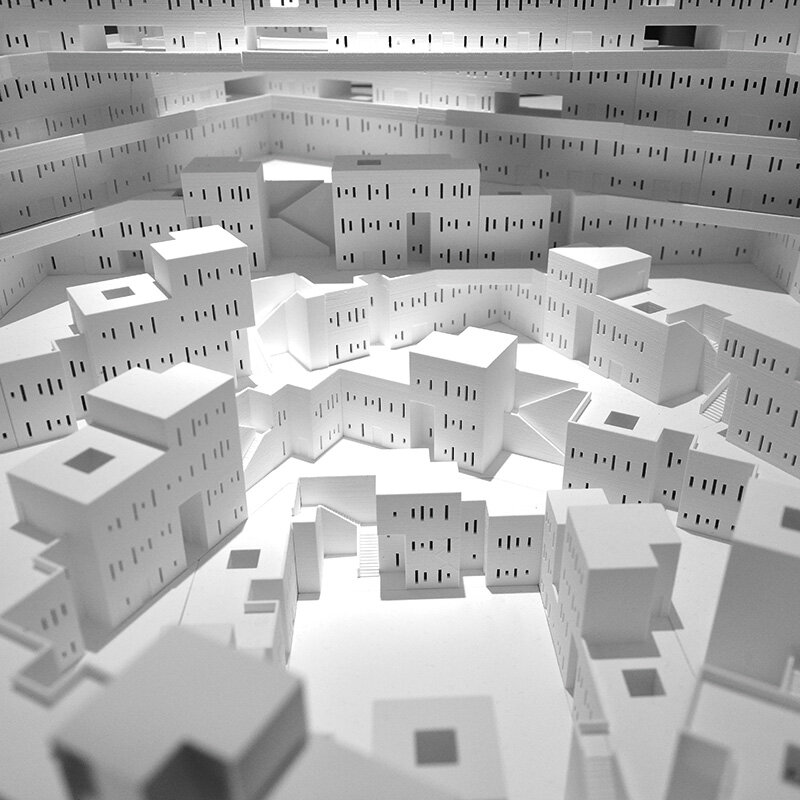

However, the environment where the authentic Singaporean spirit characterized by rituals and events is revealed is at street level. While residential towers dominate the urban landscape, the public spaces at street level have been planned as a continuous and coherent chain to create a vibrant urban experience and facilitate interaction. It is a collective housing system conceived and designed for the type of resident who, by nature and tradition, likes to share and has a desire to live in community.

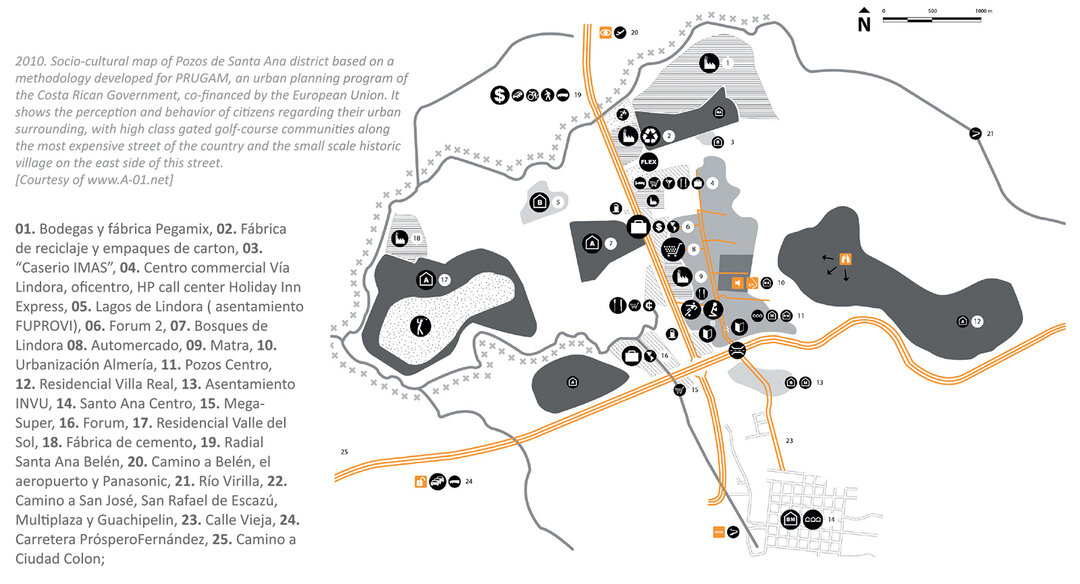

As a result, when one makes their way through the city from one neighborhood to another, from China Town to Little India, they will discover a multitude of different cultures performing their daily routines and rituals on an open urban stage in close proximity to the street and the apartments in a space called Void Deck. As a fluid space at the ground floor level of residential towers and as a specific typology for Singapore over the past 40 years, the Void Deck has played an important role in intensifying community life and had become a mythic space in the collective and personal memory of residents.

By tracing the history of the development of public spaces starting from vernacular typologies and early collective public housing, we will be able to use the changes over the years to define the cause and role of the Void Deck space as a semi-private platform for interaction.

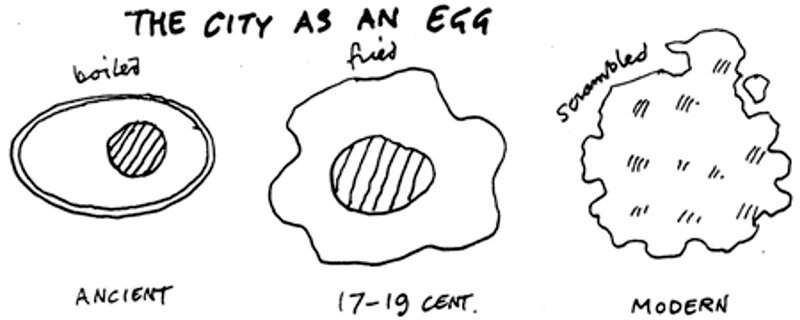

From the earliest forms of vernacular houses, we can identify the tendency to dissolve the boundary between the private realm of housing and the public realm of the street.

The traditional Kampong Malay traditional house was built on specific compartments to accommodate men and women separately, as the practice of Islam forbids uncontrolled socialization between men and women. The verandah (serambi) of the Malay house, prominent in engaging the public domain, was reserved for men to welcome casual visitors. For women, the back of the houses functioned not only as a kitchen (dapur) but also as a place to socialize with other women. Another important public area was the area beneath a thatched structure attached to the front of the house. Places of state were placed along the edge of this shelter to facilitate domestic activities in interaction with casual and spontaneous street events.

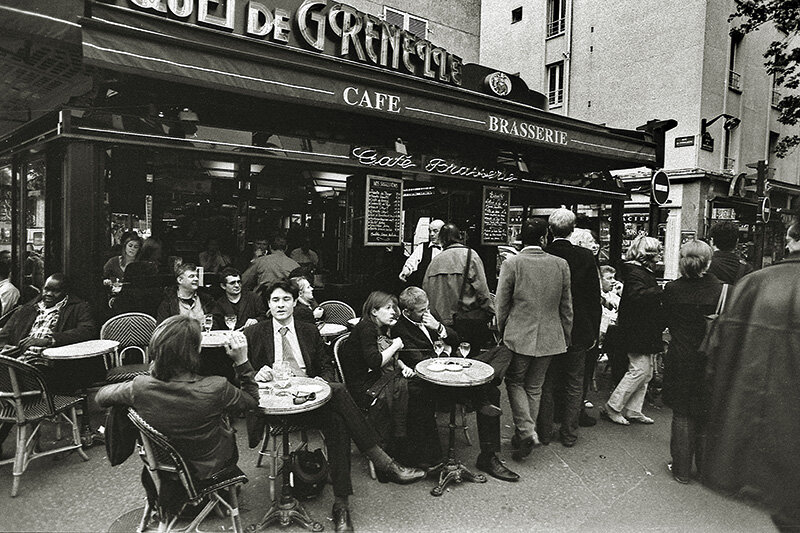

Similar to the Malay house, in the Chinese Kampong house, the corridor around the house was an area that allowed visibility to the public. Women, with the exception of very young children, were not allowed to walk around the village for the purpose of seeking social interaction, hence this corridor constituted the social space for women. As for the men, they were not restricted to the immediate surroundings of the houses, their social space being the village café, which was, in fact, a wide open shop facing the street, with tables and chairs set out in the public space.

In both types of villages, the front doors of the houses were always open so that activities could flow from inside the house to the outside, seeing the street as an extension of their own personal space. Therefore, no passer-by could avoid being seen by one villager or another, either from inside the houses or standing at the other meeting points. Under such general surveillance, everybody's view of the village was that 'everybody knows everybody'. This familiarity was perceived as contributing to residential stability in the locality.

Read the full text in the double issue 4-5 / 2014 of Architecture Magazine

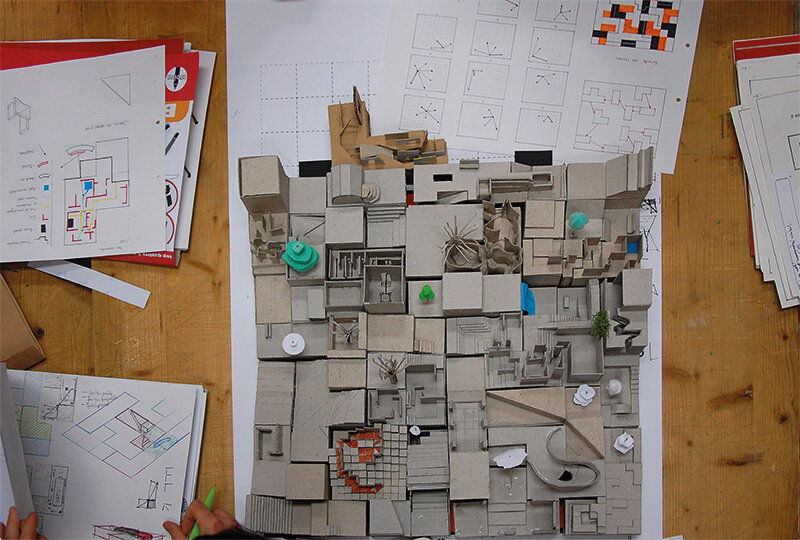

Photo: Kamilla Csegzi, Kelvin Ng

Bibliography

Goffman, Erving, Behavior in Public Places: Notes on the Social Organization of Gatherings, New York: Free Press of Glencoe, 1963

Hashim Wan, The Traditional Malay House, Penerbit Fajar Bakti, 1997

Lefebvre, Henri, The Production of Space, Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1991

Liu, Thai Ker, Design for Better Living Conditions, Public Housing in Singapore, A Multi-disciplinary Study, Singapore: Singapore University Press for Housing and Development Board, 1975

Ong, Aline K., Housing a Nation: 25 Years of Public Housing in Singapore, Singapore: Maruzen Asia for Housing &Development Board, 1985

Saat, Alfian, Void Decks, in One Fierce Hour, Singapore: Landmark Books, 1998