Public space - a bar counter?

"In the beginning was the word"...

According to A. Pleșu, (1) Gershom Sholem invokes the Aramaic version of the text according to which, through the breath of God, man "came to life", becoming not a "living soul" but a "speaking spirit".

According to Heidegger in "das Wort" : "there is no life without word and word without life". The experience of Frederick the Great (who forced to be silent the nursemaids who cared extremely well in terms of food and hygiene for two newborns and who died because no one was allowed to speak to them) proves the ontological role of communication through the word.

But is communication only through words? Art, architecture, along with all the visual arts, communicate best through the emotions they convey and above all through the explicit lack of limitation of this emotion, through semantic limitlessness and freedom of choice inherent to each individual sensibility.

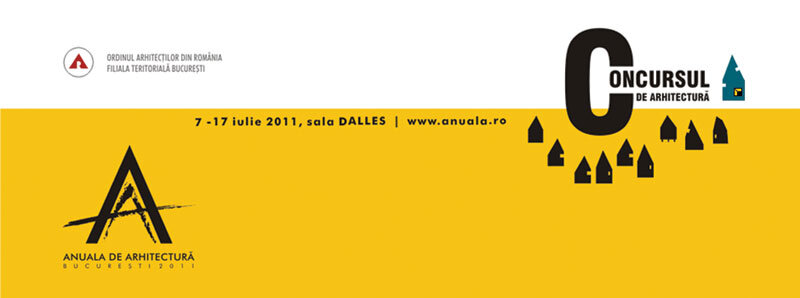

"Spoken architecture, or architecture that speaks, or the metalanguage of architecture, this is the message of the "Architecture Days 2011" session. Seeing these marvelous proposals for a cultural menu, a veritable architectural maieutic that overflows from the virtual matrix of a website and floods the city, a notion comes to mind, that of the "elixir of youth". An exuberance of manifestation, an energy and vibrancy of enormous and contaminating force is bursting forth.

Events like these mark our existence, lifting us out of its grayness and monotony. They unite us in communication. They enrich our soul and spirit. They make us better, more generous, and make us euphorically feel the meaning of our fleeting lives. For they remain in the memory of each of us like a spark of light. Later on, when the quick fires have died down, their smoldering flames warmly illuminate the silence of our memories. And they, the memories, comfort our thoughts like an elixir.

At the same time, these days stir our older thoughts about the charm and fragility of the ephemeral. The ephemeral consumes itself in that tension of the feeling of the moment, of the fleeting and the fleeting. Sights, sounds, words, movement, movement, thoughts and shapes will wander before our eyes and the thirsty crowd of experiences. And not just any experiences, but artistic, linguistic or architectural ones, true "cultural quants" as Umberto Eco would say.

They will be like flashes, the more perishable, the "stronger", the more powerful, the more vivid. For the spirit of time is that of movement, slipping, distortion, deformation, dematerialization. But also of energizing space, of refocusing, of play, of the playful, and why not, of frivolity. For frivolity means crumbling in Latin, but also grace and delight in French. Paleologu (2) says that "geometry, metaphysics and tragedy are the products of frivolity, without which there is no grace, no style, the preconditions of greatness". For frivolity for Nietzsche means "dancing in culture" or a certain English "dandyism" or a certain English "dandyism" and also a certain French relaxation, detachment, humor and grandeur. And in what "dance in the culture of their time" did our great predecessors like Brâncuși, Cioran, E. Ionesco, Blaga and Eliade!

All these fulgurings are alive as long as we remain conscious of the past. Of the passing. Of history. Of memory. For, as Aristotle says, "in reality proper, only the past exists, because it has the form "enteleheia", that is, fulfillment.

And behold, not matter but style remains, not papers but facts, not words but their meaning, not sounds but music, not events but their emotion.

And yet... according to Luiggi Snozzi (3) "Architecture is the expression of permanence... It gives man points of reference for his orientation, without which man is lost... It 'opposes the ephemeral'... This is the first fundamental thing. The second is the "anti-efficient" character of architecture. For example: displacement and path. You can do it in five, seven minutes, but good architecture gives you half an hour. When it's brilliant you can spend fifteen days with it. Architecture expands your time by creating extraordinary moments of existence." Le Corbusier stayed at the Parthenon for 45 days in an ecstasy and rapture with fertile and creative consequences for later not only his career but, we might say, for all architecture in the world after him. "In this way, through its two fundamental aspects: permanence and anti-efficiency, architecture opposes a society of ephemerality, consumption and efficiency. Today's society. True architecture is timeless and it is one of the present that lives with history without aggressiveness, in relations of common sense and responsibility. Architecture, through its perenniality in relation to our lives, even if ephemeral on a cosmic scale, offers a synchronized view of its stages and their evolution, evokes the taste of the times and its creators, speaks of building techniques and is loaded with symbols, sometimes as yet undeciphered. It is, as Umberto Eco would say, a concentrate of cultural quants. Augustine John says of Westminster Abbey, whose stylistic evolution has spanned several centuries, "what would otherwise be inaccessible becomes comprehensible by a simple journey from east to west". (4)

The architect's specialty is space. Nothing else. That is why the architect is a generalist. And if the good doctor is a generalist who also takes care of the patient's soul in order to heal him, the architect is duty bound to guide the human soul through the sensations he instills in the place he creates for it. And in the face of the constant mutations to which the evolution of the earth is subjecting us, we must strive to preserve the fundamental human values that society seems to have forgotten in recent decades.

Beaudelaire says that progress is not about increasing the speed of travel, but about reducing the distance between man today and his origins - see the essence of things.

The exact sciences and the positivism of thought that began in the 18th century have, of course, increased the speed of travel, but they have not touched the essential problems. Europe is sick because it has forgotten the essence of the problem, says Eliade. It is because of this positivist and atheistic thinking that the 20th century has gone through its most serious and monstrous trials. The 21st century, in no more than eleven years, has almost surpassed the previous one in the unprecedented manifestation of evil. Evil is no longer the pole of good. The poles are no longer clearly delineated, with limits that can be localized and spotted. Evil disguises itself in the midst of good and attacks in a chaotic, irrational and ferocious manner. Historical enemy armies, with hierarchized rules of the game and hierarchized norms, have disappeared. Guerrilla warfare, terrorism and information warfare have taken their place.

Spatial boundaries have disappeared, geographical location is no longer important. Disguising lies as truth, evil as good, the real as the imaginary have become means and tools of war. September 11, 2001, tsunamis, African wars, earthquakes have multiplied, the capture of Osama Bin Laden no longer impresses us. The world is confused, the abyssal axis has toppled.

All this expresses, alas, the spirit of the times, the zeitgeist that, in fact, every age has had. The zeitgeist, we know today, encompasses the entire thought of an epoch, with its arts, sciences, and ideologies. Well-bounded mass space expressed historical thought until the 18th century and corresponded to Euclidean geometry. Newtonian thought was matched by the abstraction of space and the emergence of the notion of infinity. The virtual entered mathematical and physical computation. The introduction of the fourth dimension of space into spatial calculus replaced geometry in space with topological geometry. Quantum mechanics and atomic theory were able to express themselves abstractly, like Laplace in his ten volumes on the composition of the cosmos (5), without the use of images.

The West is becoming increasingly iconoclastic. (Gilbert Durand). The exact sciences and analytic geometry ended up suppressing images not only as illustration, but especially as representation of the sacred. This is how we ended up with the "castration" of the image as a tool, of the imaginary as a model of creation and of that "mundus imaginalis" (Henry Corbin) as a medium of manifestation in knowledge. (6)

Descates and Voltaire also took the first steps towards demythologizing religion, and Marx and Lenin continued their work in the social and ideological space. Nietzsche gave the coup de grace to the sacred with his "God is dead". His desperate cry propelled the Western world into what Sergio Givone calls the "disenchanted period". (7)

From the Newtonian perspective, the idea of homogeneous, isotropic, absolute, infinite space has always been interpreted as profane, atheistic space. References to modern urban space, in which mass is instilled in a vacuum propagating omnidirectionally to infinity, cannot escape anyone. The period corresponds to the Nietzschean nihilism and atheization that dominated the European 20th century.

"Modern man (says Hannah Arendt), when he has lost the certainty of the world to come, has been thrown into himself, and all that remains is life itself" (8), and the city today, says Sloterdijk, "looks less and less like a stage and more and more like a screen, transparent and isolating, cold and devoid of any depth, on which reruns of episodes from a banal soap opera are playing, as in a television shop window". (9) And Ciprian Mihali asserts that "the poverty of determinants of public space pales before the abundance of virtual dimensions of new spaces or even the abundance of virtual spaces." (10)

So was the use of the grid during the modernist period an exercise in concretizing the homogeneity of space? And now can the negation of the hegemony of the grid and its recomposition in terms of heterogeneity, axiality and anisotropy lead to a recentralization, a re-axialization in an abyssal sense? Can we speak of a reenergization, refocusing of space, a rehierarchization? A resemnification? A resacralization of the receptacle?

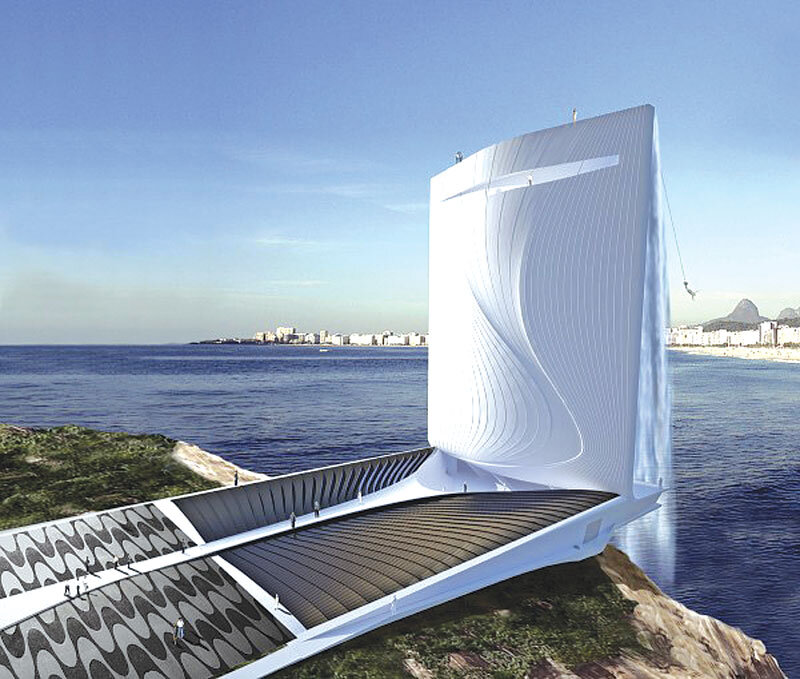

Fractal geometry, possible only in terms of the computer as an instrument of spatial representation, presupposes the reproduction of the "different" identical under the conditions of preserving unchanged essences (see spatial relations). The image, the virtual, the imaginary return in force and multiply, proliferate, develop, slip, slide, recreate themselves continuously as in the works of Zaha Hadid. Barely recovered in recent decades, the context, seen in the postmodern terms of Venturi and Moore, or in the inclusivist terms of Ada Louis Huxtable, is once again being destroyed in order to remake it in parametric terms, a permanent destruction and remaking, demiurgic and at the same time diabolic (Diabollein means to undo, to destroy, while synballein - syn-ballo - means to gather together what has been thrown away) (11)

Space has no more patience, the place, just reinstated in its rights through the works of Heidegger and the pleleiad of theorists who confer to it the noble mission of restitution and recreation of identity, is once again demythologized. It is no longer charged with memory, emotion, belonging to a culture, it is no longer identitarian. Space is "smooth or striated" according to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, "folded" according to Greg Lynn, "interstitial", i.e. empty according to the Californian school, or simply "stenic". Postmodern architecture "dematerializes the limit or disguises it through methods of blurring, mixing, overlapping and parallelism, camouflage, expansion or extrusion" (12).

To the desacralization of time in the nineteenth century corresponds a much later desacralization of space, and Foucault (13) tries to make us understand that this gap has not yet exhausted the total desacralization of space. There is still room for it.

The city no longer has public places or spaces because they do not actually exist in themselves. They only become public space when charged by the crowd. Only if they are full. Sociologists, philosophers teach us that space is political (Henri Lefebvre), the abstract and the virtual are so present that public space is confused with civic attitude or civic spirit. The language of space itself no longer exists, architecture as space can no longer express anything. Artificiality, exclusion, nudity, the public square simply becomes the square. Architecture has to promote relationships, to be relational, that is, to allow socialization, public space is more like a bar counter. It must produce communication, it must be civic, it must therefore be efficient, in the opposite sense to Snozzi's theory.

So we architects would like to create places, public spaces, but how? How to bring people into our architectural space, how not to repeat what has been done before? We like historic squares a lot, but why don't we at least try to understand why they are so busy, so full of life? Is it because they are introverted, heterogeneous, charged with collective memory, recognizable, unique, harmonious, unitary? Does St. Mark's Square in Venice no longer impress us if we visit it at five in the morning, when it is, of course, empty of crowds? Does it no longer carry a message? No longer identitarian? Just a heterotopia of Venice?

Identity is the assumption of the culture of your time and its exercise should be done without excluding the continuity of form. Is it, identity, already so obsolete without having been exercised at least a little in terms of the new contemporary zeitgeist?

This preservation of cultural identity is STILL at stake in our sick Europe. Even if Europe ultimately becomes a cultural museum rather than an all-powerful force in the world.

NOTES:

1. Andrei Pleșu, The Language of Birds, Ed. Humanitas, Bucharest, 1994 2. Alexandru Paleologu, Bunul simț ca paradox, Ed. Cartea Românească, Bucharest, 2005 3. Luiggi Snozzi, ENSHA Conference, Hania, Crete, 2009 4. Augustin Ioan, Ciprian Mihali, Dublu tratat de urbanologie, Ed. Ideea Design & Print, Cluj, 2009 5. Laplace wrote the ten volumes of "Celestial Mechanics" without using any illustrations and without mentioning the word God, cf. H. R. Patapievici, Cerul văzut prin lentilă, Ed. Humanitas, Bucharest, 1994 6. H. R. Patapievici, Op. 7. Sergio Givone, Le Sacré, Cahier de philosophie, nr. 17, Lille 1993/1994 8. Idem note 4 9. Ibidem 10. Ibid 11. Adriana Matei, Teorii și doctrines arhitecturale contemporane, Ed IPC, Cluj, 1994 12. Ileana Stanciu, Locurile intermediare: arii vagi, arii de mediere, Ed. UAUIM, 2007 13. Michel Foucault, Altfel de spații, theatrum philosophicum, Ed. Casa cărții de știință, Cluj, 2001