BIGNESS între teorie și practică

BIGNESS

between theory and practice

| Bigness: „Dincolo de o anumită masă critică, o clădire devine o mare clădire. O asemenea masă nu mai poate fi controlată printr-un simplu gest arhitectural, nici măcar printr-o combinație de gesturi arhitecturale. Această imposibilitate declanșează autonomia părților constituente, ceea ce nu este același lucru cu o fragmentare: părțile ramân supuse întregului”.1 |

| Citatul de mai sus este primul dintr-o serie de patru puncte (Theorems) - cărora li se adaugă în 1994 un al cincelea - enunțate de Rem Koolhaas, care vor bulversa peisajul arhitecturii ultimelor decenii. Cred că aspectul cel mai frapant este faptul că arhitectura și urbanismul - pe de o parte - teoria și practica - pe de altă parte - se regăsesc reunite într-o indisolubilă coeziune. Nu este puțin lucru într-o vreme când - rezultat al unei acerbe concurențe - „specializări” de toate felurile își dispută prioritatea.

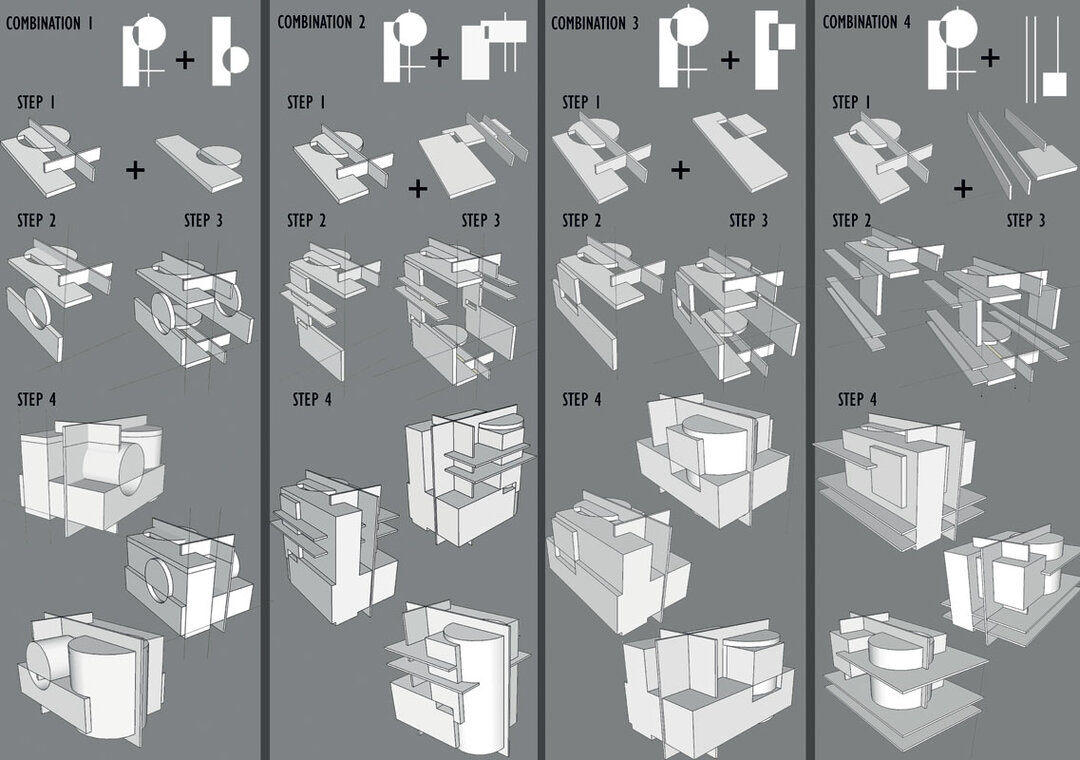

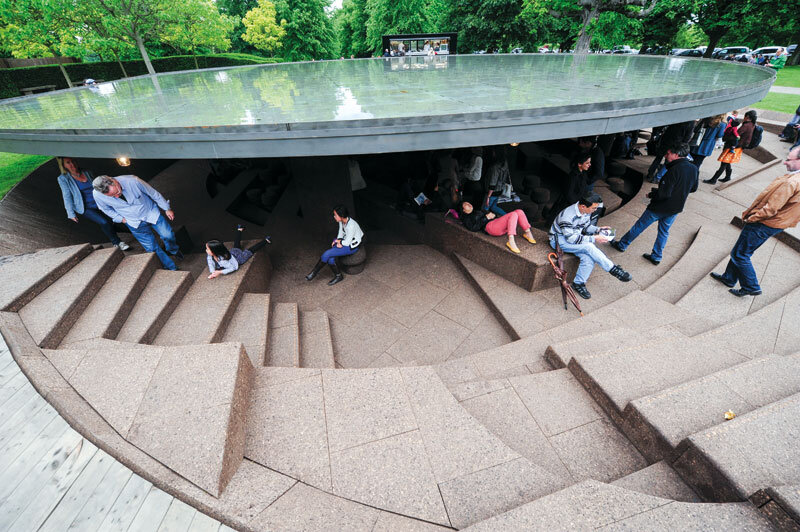

Este, în același timp, o adevărată subversiune, incomparabil mai virulentă decât scrierile lui Venturi. Compoziție - urbană și arhitecturală -, principii, ierarhii, categorii, modalități, sunt excluse de pe terenul concepției și al proiectării în favoarea unei generări „procesuale” (architecture - trough - process2). Argumentul: ocuparea maximală a gabaritului urban permis și satisfacerea simultană a unei multitudini de programe, fără a neglija situații evolutive. Modelul: Down Town Athletic Club3, un „mini” zgârie-nori construit în 1930 la New York de Starrett și Van Vlack, nu pe baza unei formalizări cutumiere, ci printr-o „extrudare verticală”. Secțiunea verticală a imobilului în „benzi paralele”, beneficiind de o anumită autonomie, a fost utilizată și pentru Concursul pentru parcul de la Villette la Paris4 (1982-1983), de data aceasta rabătută la orizontală. |

| Citiți textul integral în nr 3/2012 al revistei Arhitectura. |

| NOTE:

1. “Beyond a certain critical mass a building becomes a Big Building. Such a mass can no longer be controlled by a single architectural gesture, or even by any combination of architectural gestures. This impossibility triggers the autonomy of its parts, but that is not some as fragmentation: the parts remain committed to the whole”, în S, M, L, XL - OMA, Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Man, Rotterdam - New-York, 1995 (pag. 499, 500) 2. OMA, Urban Intervention: Duch Parliament Extension, The Hague-International Architect no. 3, v. 1, 1980 (pag. 50) 3. Jaques Lucan OMA - Rem Koolhaas, Electra Monitor, 1990 (pag. 66) 4. Jaques Lucan, ibidem3 (pag. 57, 58) |

| Bigness: „Beyond a certain critical mass a building becomes a Big Building. Such a mass can no longer be controlled by a single architectural gesture, or even by any combination of architectural gestures. This impossibility triggers the autonomy of its parts, but that is not some as fragmentation: the parts remain committed to the whole”.1 |

| The above quotation is the first of a series of four Theorems - to which Rem Koolhaas added a fifth in 1994 - that were to throw the architectural landscape of the last few decades into turmoil. I think that the most striking aspect is the fact that architecture and urbanism, on the one hand, and theory and practice, on the other, can be found united in indissoluble cohesion. This is no small achievement in an age when, as a result of fierce competition, all kinds of „specialities” vie for supremacy.

At the same time, it is genuinely subversive, and incomparably more vehement than the writings of Venturi. Urban and architectural principles, hierarchies, categories and modes yield their place in the field of conception and design to the generation of „processes (architecture - trough - process2). The argument: maximal occupation of the allowable urban template and simultaneous satisfaction of a multitude of programmes, without neglecting evolutional situations. The model: Down Town Athletic Club3, a “mini” skyscraper built in New York in 1930 by Starrett and Van Vlack, not on the basis of traditional formalisations, but by means of “vertical extrusion”. The “parallel striped” vertical section of the building, enjoying a certain degree of autonomy, was also entered into the Compe-tition for the Villette Park in Paris (1982-1983)4, this time rotated horizontally. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |

| NOTES

1. “Beyond a certain critical mass a building becomes a Big Building. Such a mass can no longer be controlled by a single architectural gesture, or even by any combination of architectural gestures. This impossibility triggers the autonomy of its parts, but that is not some as fragmentation: the parts remain committed to the whole”, in S, M, L, XL - OMA, Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Man, Rotterdam - New-York, 1995 (p. 499, 500) 2. OMA, Urban Intervention: Duch Parliament Extension, The Hague-International Architect no. 3, v. 1, 1980 (p. 50) 3. Jaques Lucan OMA - Rem Koolhaas, Electra Monitor, 1990 (p. 66) 4. Jaques Lucan, ibid3 (p. 57, 58) |