In search of wine's beginnings

"For Georgians, wine is God"

"For Georgians, wine is God," my Georgian friend Otar says to me quite by chance, in the middle of a conversation on a completely different topic, as we look down from high above, in the middle of a hot summer, seated on a terrace in the hills, on Tbilisi, the Georgian capital, with its eclectic and particularly interesting architecture. His words came naturally, in Romanian, because Otar was a student in Timisoara and speaks perfect Romanian. I met him before the pandemic, in Tbilisi, looking for a translator for the texts for my exhibition on urban markets at the National Museum of Georgia. His random sentence gives the title to my article on the beginnings of wine because I found them a good, perfect even, summary of a country and a wine tradition that fascinates me.

This is my fourth time in Georgia and I would return again and again. Georgia and the Caucasus as a whole is a kind of anthropological initiation, a necessary way of understanding ancient worlds and what has been preserved from the distant past until today, with all the natural transformations. The present is no less interesting. The geographical space between the Black Sea and the Caspian, bounded to the north by the Greater Caucasus, with Elbrus, Europe's highest peak, and to the south by the Lesser Caucasus, comprises three relatively small countries - Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia, plus, on the northern slopes of the Caucasus, several even smaller republics of the Russian Federation. But many more cultures, ethnicities, histories. It's that part of the world where Europe becomes Asia and Asia becomes Europe, without geographers ever agreeing on where the boundary between the two continents can be drawn unequivocally. In March, in Azerbaijan, I climbed Khinalug, one of the highest permanently inhabited settlements in Europe - if in Europe. An isolated village of just over 2,000 people, it speaks its own language, unrelated to the surrounding languages, with traditions distinct from the rest of the country. Historians have put forward various hypotheses about the origins of Khinalug's inhabitants, none of which are convincing and with sufficient evidence to support them, and linguists are nowhere to be found to trace the origins of the language spoken here. The settlement, which has received some tourist fame of late for reasons of its altitude record, which can only be reached by 4x4, remains a mystery in this respect. The example is not unique, the Caucasus actually offers plenty. Over 50 ethnicities, about as many or more languages - depending on how you count them, including languages only oral, unwritten and unschooled in schools, still alive, all in a very small geographic space to fit so much diversity. The Caucasus cannot be compared to any other part of the world in this respect. Christianity, Islam, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism - in Kalmaks, animist shrines on mountain slopes, in the Tukhaz and elsewhere, in direct continuity with religious practices from prehistoric times. Until the not too distant past, communication between one part of the Caucasus and another was extremely difficult, and in fact remains difficult today. The valleys are deep, the mountain peaks cannot be cut at a walking pace because they are too high and steep. Virtually every region has historically had a great degree of isolation, so over time it has acquired distinct customs and cultural nuances distinct from those of neighboring valleys. In Georgia, two of the provinces, Tușeti and Khevsureti, are even today completely cut off from the rest of the country in winter, because the roads to them climb to almost 3,000 meters in altitude and there is no more than one road to get there. And yet, in simply passing through the different parts of the Caucasus, the traveler's eye catches enough commonalities of material culture. Worlds that are different and at the same time connected. The Caucasus is the classic argument of anthropologists against archaeologists who often assume that if the same or similar elements of material culture emerge from different archaeological sites, these sites once belonged to the same culture. In the Caucasus, ethnicities may not share a common language and origin, let alone religion, but a red thread of material culture exists between them.

Not far from Romania, just across the Black Sea, a thousand kilometers as the crow flies, the Caucasus is an area that is similar in many ways. The traveler's eye quickly picks up something similar to home, because the countries there have gone through Soviet communism, because the post-communist "transition" there follows much the same thresholds, sometimes steps behind, sometimes steps ahead of Romania. The world beyond the sea resembles us, because part of it is Orthodox, because the Ottoman influences are the same or similar to those in Romania, from food to some manners, because the cultural Europeanization, immediately visible in the architecture of the cities, happened there too, quickly and convincingly, in the 19th century, towards the end, and at the beginning of the 20th century. It is strange, therefore, how little is known in Romania about Georgia and the Caucasus in general. Throughout the world, the Caucasus countries are far too little known, brought into the spotlight from time to time by the flare-ups of the fizzling military conflicts of the post-Soviet era.

Beyond a rapidly changing and modernizing present, the Caucasus remains a region of beginnings. Unlike the general public, the international scientific world often has its eyes riveted on the evidence emerging from the countries of this corner of Europe and Asia. In Georgia, in Dmanisi, for example, in the early 1990s - a remarkable discovery! - the oldest humanoid skeletal remains in Europe, estimated to be no less than 1.8 million years old. From the Caucasus comes perhaps the oldest preserved carpet of mankind to date, woven in the 4th-3rd centuries AD, but unearthed from a tomb in the Altai in the 1950s, proof that the world has been around since times we now imagine as static, although they were not. Or perhaps more famously, Armenia is the first country in history to officially recognize Christianity as a state religion, in 301, a merit sometimes claimed by Georgia, although historians agree on 319 as the year when the country adopted Christianity as its official religion. That's why churches of remarkable antiquity survive in the Caucasus, some dating back to the first centuries after Christianity. They are built with a marvelous architectural science of light that penetrates the interior according to the rhythms of the religious calendar. On the exterior walls of many Caucasian churches there are bas-relief carvings of the vine, which is not just a decoration, but of course has a mystical and sacred meaning. More deeply rooted in history than in churches in other parts of the Christian world, because, among other things, the Caucasus is also the birthplace of wine, long before Christian dogma appeared on earth.

By the time Noah got drunk

I have taken a bird's-eye view of the Caucasus in a hurried flight, because the history of Georgian wine cannot be understood and does not have the same flavor without putting it in the frame - little and too briefly than I would like, I could tell about the Caucasus from my travels. Anyway, wine - you know this - is about stories, and when you know the stories surrounding it, it takes on a different flavor, you drink it differently, more fondly and make friends faster.

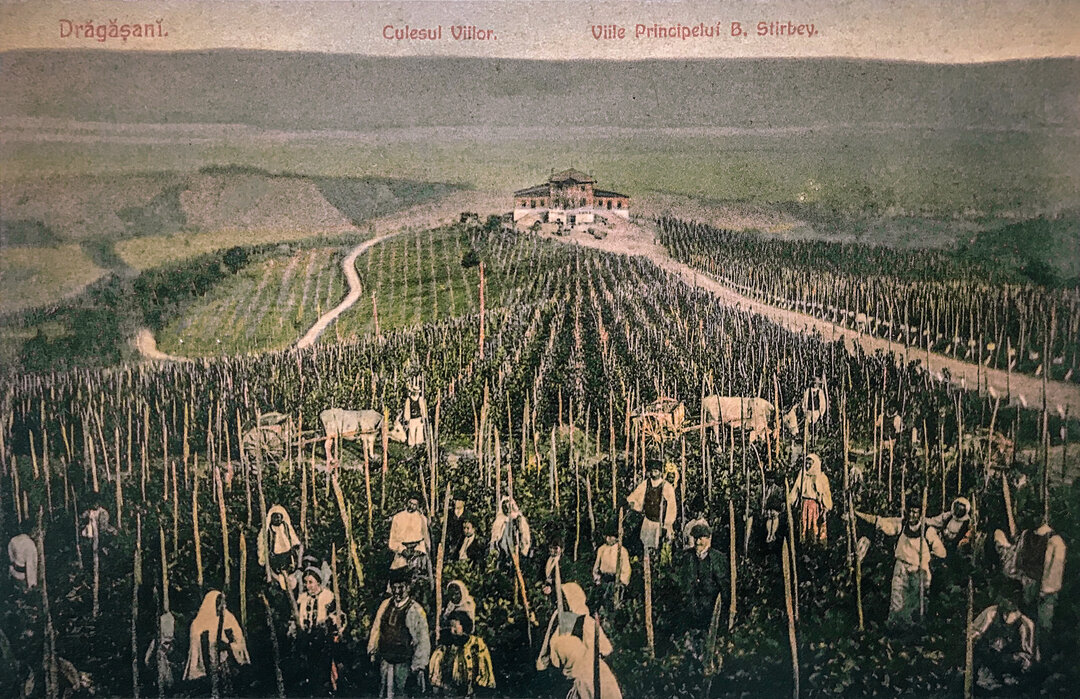

The story of Georgian wine is, in fact, the story of the origins of wine the world over. Historians today seem to agree that Transcaucasia is the original homeland of the grapevine, and it was also here that the first wine was made by prehistoric people. Biblical legend has it that Noah, carried by chance by the waters of the Flood, came to Mount Ararat, the later holy mountain of the Armenians, and planted vines. He made wine and got drunk. Since there is nothing in the Bible before Noah about vines, this must have been the first ritual drunkenness, and therefore the first real drunkenness in human history, and in sacred history at that. At the foot of Mount Ararat are the sources of the waters that feed the legendary Tigris and Euphrates rivers, real geography becomes symbolic and sacred geography there, and it is no coincidence that the first wine was fermented there. That way, but perhaps not exactly there, because the evidence discovered by archaeologists leads just a little north of Ararat, in today's Georgia, 8,000 years ago. And it's very recent finds that have confirmed present-day Georgia as the birthplace of the first wine in human history.

In 2017, pottery remains unearthed in archaeological excavations at a site in the village of Shulaveri Gora in Shida Kartli province, about 50 kilometers south of Tbilisi, were subjected to careful and repeated biochemical analysis. These showed that wine had been stored in the vessels from 6000-5800 AD, the Early Neolithic period. Not ten kilometers away, pottery from another equally important site, Gadachrili Gora, confirms the dating and the presence of tartaric acid in the remains of the clay vessels, which is evidence of the fermentation process of the grapes.

The discoveries at Shulaveri and Gadachrili Gora push back at least half a millennium the age of the earliest historical evidence of grape fermentation and wine-making, with previously known evidence dating to between 5400-5000 AD from the Zagros Mountains in today's northwest Iran. Historians had long since established that around 6000 AD, people established permanent settlements throughout the Transcaucasus region and began to cultivate plants, domesticating wild varieties. A wild variety of the Eurasian grapevine, called by specialists Vitis vinifera sylvestris, which still today grows in abundance and absolutely randomly at fairly high altitudes on the limestone and semi-arid coasts of Georgia, but also in our own country or in the Mediterranean area, must have been planted and adapted for cultivation by the people of those times so far removed from us. Adaptation to cultivation meant selecting over time plants that produced larger, juicier and tastier grapes than the wild variety. In addition, compared to the wild variety, the cultivated vine had the advantage of self-pollination, which reduces species variation and makes future grape production predictable: the wild vine has both male and female flowers. The male flowers are for pollination only and do not produce grapes. The development of hermaphrodite varieties is considered by paleobotanists as evidence of the species' passage into cultivation. Just as probably, the inhabitants of the Neolithic Caucasus learned fairly quickly to propagate vine varieties by cutting, a technique that led to the spread of plantations identical to the plants already selected, while recessive plants, unpredictable in terms of the richness of grape production, grow from seed. Once vine-growing takes root in the Caucasus and the skill of wine fermentation is perfected by prehistoric people, viticulture spreads southward, to Iran and then to the whole of the Near East... From there to Europe... And from Europe, wine-making skills reach the New World... We're not talking years or decades, but millennia.

Spectacularly, the science of phylogenetics almost millimetrically validates the story of Noah's planting of the first vines after the flood in parts of the world south of the Caucasus. DNA analysis of ancient western European grape varieties such as Nebbiolo and Pinot Noir has proven genetic kinship with varieties still existing today in Georgia, such as the endemic Otskhanuri Sapere, which grows only in the Georgian provinces below the Caucasus, Racha and Imereti. However, it is known with certainty that the oldest vine still in cultivation is a white Georgian variety called Rkatsiteli. It is the most resistant to phylloxera and frost, although sensitive to prolonged drought. Cultivated for at least 5,000-6,000 years and probably originating from the magnificent Alazani valley, its name can be found on the labels of the amber-colored wine bottles that line Tbilisi's shops. It is also worth noting that there are over 525 endemic grape species in Georgia today, an impressive figure which supports the hypothesis that grape-growing originated in the prehistoric Caucasus. Georgia's varietal diversity was noted as early as the 17th century, when the French traveler Jean Chardin noted that no country surpassed Georgia in the quality and variety of its wines.

Today Shulaveri Gora is just another village in Georgia, at an altitude of about 1,000 meters above sea level, and the semi-arid climate is perfect for growing grapes. 8,000 years ago, the climate must have been quite different. Researchers at the University of Milan, led by Osvaldo Failla, have reconstructed the climate of the 6th millennium AD and concluded that it was even more suitable for vines in these regions.

But what was life like for the people who made history's first wine? It's hard to say, archaeologists are largely doing detective work and there is no key to validate their hypotheses. We do know that the area where Shulaveri Gora is located was the center of a Neolithic culture that extended as far west as Azerbaijan and northern Armenia. By the end of the last Ice Age, the area's climate had become warm enough to allow agricultural crops. With the 'taming' of the first grasses, sedentary life became possible and early Neolithic people lived in round clay houses. Presumably this form of round dwelling has something to do with an early form of religion. Presumably sedentarization gives them the time to practice and develop what we later call architecture and arts of all kinds. It is also to be assumed that wine would not have been just any drink, but one with a strong sacred component.

Anthropologists believe that wine was from the beginning part and even center of religious life. Wine cut through pain, numbed it. It is known that from early times it was mixed with conifer resin, probably initially for a purely practical reason, the resin was intended as a preservative. But it enhanced the wine not only in taste, but also in its medicinal, antibacterial properties, which, to the people of the time, more than likely seemed a sign of an otherworldly force. But it's more than that. The process of fermenting wine must have stirred people's imaginations quite a bit, and must have been thought to be a manifestation of a divine and mystical force, uniquely capable of transforming a sweet liquid into one with euphoric, mind-changing and human-euphoric properties. In all later eras, wine was part of religious ceremonies, charged with sacred forces and transcendental symbolism. It is only millennia later, to the present day, that the mystery of wine fermentation has been given a purely physical and chemical explanation, but one which, let's face it, has not completely destroyed either the mysticism or, still less, the euphoria that must have been felt, first of all among all men, when the world was so fresh that even wine had no name, by a peasant from Shulaveri Gora, who, by chance, 8,000 years ago, on a too-warm day, crushed wild, overripe grapes. And that he left them for a couple of weeks in an earthenware pot, only to discover that their water changed his sadness into joy, let him see the world around him differently, and the future ahead in unsuspected and unutterable colors before drinking a little and a little more of the ruby-red and sacred liquid...

While on the subject of wine's name: linguists, with their skill, have reconstructed the proto-Indo-European ancestor of the word "wine" from most contemporary European languages - it may well have been wéyh₁ō. Which would come, in fact, from a gesture and verbn, wéyh₁ō, meaning "to cover". Clearly, for practical reasons, the vessel in which the wine was kept had to be covered. And still on the subject of names - in Georgian, a language that has its own alphabet, developed in the early Christian centuries probably by a monk in the Judean Desert, the name of the place where the first wine in history was fermented is spelled like this: შშულავეერი. I reproduce it here for its graphic beauty.

Tamada

The archaeological testimonies related to wine in Georgian history are numerous. The western part of Georgia is even today sometimes called Colhida, as it was called especially in antiquity - that legendary land that Homer tells of, where the Argonauts came in search of golden wool. The region is full of ancient tombs, a gold mine for archaeologists. Almost literally, because the royal tombs here hide gold, silver and wine vessels, leading some historians to believe that wine was a badge of royalty and considered as valuable as precious metals.

Of the pieces unearthed from the hill-fort sites, a bronze statuette of only 7.5 cm, dating from the 2nd cent. VII-VI AD. It depicts a seated man holding a horn and drinking wine. Archaeologists immediately recognized in this statuette a scene familiar to them and to any Georgian, so the bronze man was named Tamada. Tamada is still very much alive in Georgian tradition today, the man who, at a feast, a celebration of any kind, large or small, wishes and toasts wine, which he drinks from an animal horn. For Georgians, the symbolic role of this tamada in a celebration is huge. It is practically an instantiation of Georgian life which denotes the central role of wine in this culture. There is no Georgian wedding, funeral, birthday or gathering of any kind without tamada. He is the head of the party and a common joke in Georgia is that he is the dictator of the party. No one can leave the party without asking his permission, and if he approves, the departure is accompanied by a toast to the departing party. The Tamada must be a respectable man, skilled with words and spontaneous rhymes. There are several toasts at each such meeting and each of them is opened by the tamada. The role of the tamada is to give the 'topic of the discussion', which the other meseni are not allowed to change, to link the past, present and future through his words, because the tamada's prayers are about ancestors, about what is important to the family, about the future projections of those gathered for the feast. Everything becomes solemn when the men drink the wine, to the bottom of the glass, in silence. The tamada's traditional accessory is the ram's or goat's horn goblet, called a kantsi, and no Georgian gathering is complete without a kantsi. I learned most interesting and interesting things about tamada from Otar, because once, in Tbilisi, we met the day after he had been tamada.

In Tbilisi, in the old city center, not far from Meidani Square, once one of the terminus points of the Silk Road, there is an almost human-scale replica of the statue discovered at Vani. It is the most telling and visual evidence of the central role of wine in the lives of Georgians today and for millennia. In the summer, on my last visit to Tbilisi as part of an ERASMUS project, Tamada and I toasted a glass of qvevri wine.

Qvevri. The missing link in the story of Noah

The biblical story of Noah planting the first vine immediately after the flood has a missing link and therein lies the evidence that leads us, again, but on a different path, but as sure as bio-molecular analysis, to the world's first wine. First of all, it should be noted that Noah could not have drunk the wine immediately after planting the vine, because it simply takes several years for a young vine to bud. But let us bear in mind that in sacred texts time flows differently from profane time, and let us believe the Old Testament text, beyond chronology. But Noah needed something else to make the world's first wine. And this something is not God's will, but a simple vessel. Yes, a simple vessel in which the crushed grapes could sit for a while and ferment to become wine, and the biblical text says nothing about this vessel. He is the missing anthropological link in the biblical text and he is called qvevri.

Qvevri, as the Georgians call it, is a very large clay amphora in which wine is traditionally fermented using a particular technique unique to Georgia. This vessel is identical to the Neolithic vessels found at Shulaveri Gora and throughout Georgia. Hence the assumption that it originated in Neolithic times. The Neolithic, it is known, discovered the technique of making clay pots, which they used for storing grain, honey, fruit and, lo and behold, in the then territories of the Caucasus, even wine.

However, even before biochemical analysis and carbon dating validated the age of the wine from Shulaveri Gora, it was already assumed that Georgia was the territory where the Bahian liquor was invented. Hugh Johnson, the best-selling author who has ever written about wine, formulates this hypothesis in a widely circulated book entitled The Story of Wine, published in 1989. He points to the fact that fossilized seeds of wild grapes have been found in the strata of Georgian archaeological sites dating back to the early Neolithic. The theory is further supported in the Ancient Wine volume by Professor Patrick McGovern of Pennsylvania University, a frequent traveler to Georgia, who later coordinates the team obtaining the bio-molecular samples. The age of the seeds does not convince the international scientific community, nor does the finding by archaeologists that the remains of Caucasian clay pots from the 6th millennium AD are decorated with grapes in relief, among other things. But even ethnologists and anthropologists were more certain than anyone that Georgia is the birthplace of wine. And their argument is qvevri. Not just the vessel itself and the fact that it is identical to prehistoric vessels. Qvevri is more than an amphora-shaped vessel, it is a wine-making technique that accumulates traditions and rituals around it. So simple and at the same time so complicated, because it requires skill, with countless reverberations and anchors in the beliefs, ritual practices, customs and daily life of the Georgian family, that the age of this wine-making technique is certainly lost in the most remote archaic times and can only be the first in the world, probably the technique also used by the ancient Greeks, who, it is known, traded wine with the Georgians.

Tourists arriving in Tbilisi are asked in any bar or restaurant whether they want 'European' wine or Georgian qvevri wine. Note that European wine is in fact also Georgian, but made in the way we all know and stored in oak barrels to be bottled. The first time I drank qvevri red wine, the real Georgian wine, my teeth were chattering because it's 'thick'. I didn't like it at first. From the second glass, the taste of it seemed special, unparalleled and wonderful. This is what qvevri wine really is! The mistake, at first taste, is to unwittingly compare it with wine fermented according to the 'European' technique.

In a nutshell, the qvevri fermentation technique is simple: the grapes are crushed when they reach maturity in the fall and placed in the qvevri, the vat is buried in the ground, with the mouth covered, at ground level, and the grape juice is left on the grapes until spring. Of course, the resulting red wine isn't as clear as the 'European', often more opaque and tastes quite different. The white wine is made in the same way, except that the resulting liquid is much darker than European white wine, with a clear amber color. I could describe it in layman's terms as a white wine with all the qualities of a red wine. In fact, if I may say so, it is somewhere in the middle between a white and a red wine prepared according to the usual technique.

In itself, the method of making wine in qvevri allows little variation and this explains its extraordinary stability over centuries and millennia. As simple as this method is, it is also efficient. During the fermentation period, which usually lasts two weeks, the wine in qvevri must be stirred regularly, even every four hours. The grape skins float on the surface, practically sealing the must in the vat from the oxygen in the outside air, which ensures a very efficient bacterial fermentation. Once fermentation is complete, the entire interior of the vessel is layered, as can be seen in a diagram on display at the Tbilisi Wine Museum. The seeds, being the heaviest, end up in the conical bottom of the vessel. The remains of stems and stalks form the next layer. The husks settle on top. The sediment in the wine forms the next layer, so the contact between the seeds and the wine is almost completely blocked, so the wine is prevented from taking up too much tannin from the seeds. Interestingly, the wine has different properties depending on its position in the qvevri - the best wine is the "middle" wine, drunk on holidays and special occasions, topped with tamada. After the wine is drawn over the seeds and the remains of the husks in early spring, it is put back into the qvevri and buried. Some wines, from certain grape varieties, can remain buried for up to 50 years without losing their properties, and there is a tradition that when a boy is born, a qvevri full of good wine is buried and kept until the date of his marriage.

Anthropologists and ethnologists make an important distinction between customs and traditions that have been revived or reinvented after a long disappearance - there are more examples than you might think all over the world - and those that have been continuing over time. The distinction is crucial, although to specialists in other sciences it may seem unimportant. Continuity over time almost invariably involves significant regional transformations and variations in that practice or custom, for that is the natural business of time, to transform, sometimes contradictorily and unrecognizably, practices that have the same origin. What is extraordinary about the traditional Georgian technique of wine-making is precisely the long continuity that links it to a prehistoric age that is difficult to conceptualize, coupled with great stability over time. This is why, in 2013, UNESCO inscribed the Georgian winemaking technique on the list of intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

Marani or the house of wine. Georgian winery architecture

Marani is the Georgian name for the winery, the place where the grapes are crushed, pressed, the place where fermentation takes place and then the wine is also stored in sealed qvevri. Georgians consider marani a wine house, in the sense that wine, a living being for Georgians, needs a home to live in.

In addition to its practical purpose, marani has a strong religious significance in ancient Georgia. It often happened in medieval times, and even afterwards, that churches were destroyed by invaders, and in this case marriages or baptisms were performed in marani. How sacred this space and the wine itself is speaks of an ancient tradition that demands that the grapes be mutilated silently, without words, in any case without words that would attract evil, and that anyone who violates the ritual prohibition of making no noise is subject to punishment. "For Georgians, wine is God." Historians assume that this religious function of Georgian wine cellars decisively influenced their architecture.

Throughout Georgia the organization and typology of wine cellars differ greatly from one area to another, although the functions are the same. This, of course, speaks of antiquity, and is further proof that Georgia is, perhaps, the original homeland of wine, as diversification only occurs in large historical intervals. Diversity is also a reflection of climatic variety. Although a small country - almost a third the size of Romania by comparison - Georgia has no fewer than 29 microclimatic zones. Wines also differ significantly from one area to another, and the architecture of wine cellars not only follows local tradition, but is also the result of accumulated empirical findings on how their construction influences the temperature and humidity inside the cellars, which are essential for the fermentation of grapes. The same experience gained over time decides the size of the qvevri vats.

In the eastern regions of Georgia, Kakheti or Kartli, the marani is usually a separate construction from the house, made of brick and mortar. Some of the old wine cellars preserved to this day, such as the one in Saguramo or on the Chavchavadze family estate, are declared historical monuments in Georgia, proof of the importance of the wine-growing tradition for the country's national identity. An interesting feature of these cellars is the presence of fire-glass fireplaces built into the walls, sometimes as many as three. Their purpose is not to heat the room for fermentation in the possibly colder autumns, because this is not necessary, but to ventilate the air - Georgian peasants have found over time that this is the best way to remove excess moisture from the room.

In Imereti, to the west of Georgia, the climate is different, and the wine cellars, called churistavi here, are half-open, have only three walls, and are often built of wood. Unlike in eastern Georgia, they are not near houses, but usually close to the vineyards. Custom requires that certain species of trees, such as quince, be planted near the winery. Their role - to increase shade and lower the temperature. Certainly other tree species would provide more shade, but tradition has selected those trees whose roots, as they grow, do not destroy the qvevri pots buried in the marani.

A special type of Georgian historic wine cellars are the fortified wine cellars, nowadays particularly picturesque, which are to be found mainly in eastern Georgia, or the cave cellars, such as those in two spectacular and well-known Georgian sites, Vardzia and Uplistsikhe, rock towns whose history goes back to before the Christian era.

Not least of interest are the marans built around monasteries, usually buildings attached to the north wall of churches, and Georgia is dotted with impressive stone churches, many dating from the 9th-12th centuries. There is an ancient and intimate link between Georgian Christianity and the grapevine. According to tradition, the Georgians were Christianized in the 4th century by a woman, Saint Nino, who came from Cappadocia. Her cross, which is a national symbol of Georgia, has a particular shape, with its arms pointing downwards and, not coincidentally, legend has it that it was made of vines. There are historians who say that the main reason why Georgia, under constant threat from Muslims, has resisted Islamization is precisely wine. The thesis is quite plausible, even those Georgian communities that converted to Islam in the 16th-17th centuries, such as the Adjara province in south-west Georgia's Adjara province on the Turkish border, or the Lada, who today live around Trabzon in Turkey on the Black Sea coast, publicly and unabashedly continue the wine tradition, even though their religion theoretically forbids it completely.

However, the life of Georgian monasteries has historically involved wine-making, and many of the monasteries that can be visited today display qvevri of considerable age in their courtyard. Of the Georgian monasteries, Alaverdi, situated in the fertile Alazani valley of Kakheti, the country's best-known wine-growing region, remains for me a metonymic image of the beauty of the Caucasus. The slender profile of the church, silhouetted against the high, snow-capped peaks of the Caucasus at the time of a sunset, comes to my visual memory almost every time I think of Georgia. The origins of the monastery go back far into the 6th century and the present church dates back to the 11th century. Archaeological excavations in the mid-2000s uncovered the remains of a cellar containing no less than 40 qvevri from the 18th to the 10th centuries. For the five monks of Alaverdi, it was the impetus to revive the tradition, and today the monastery produces more than 100,000 bottles of top-quality wine a year.

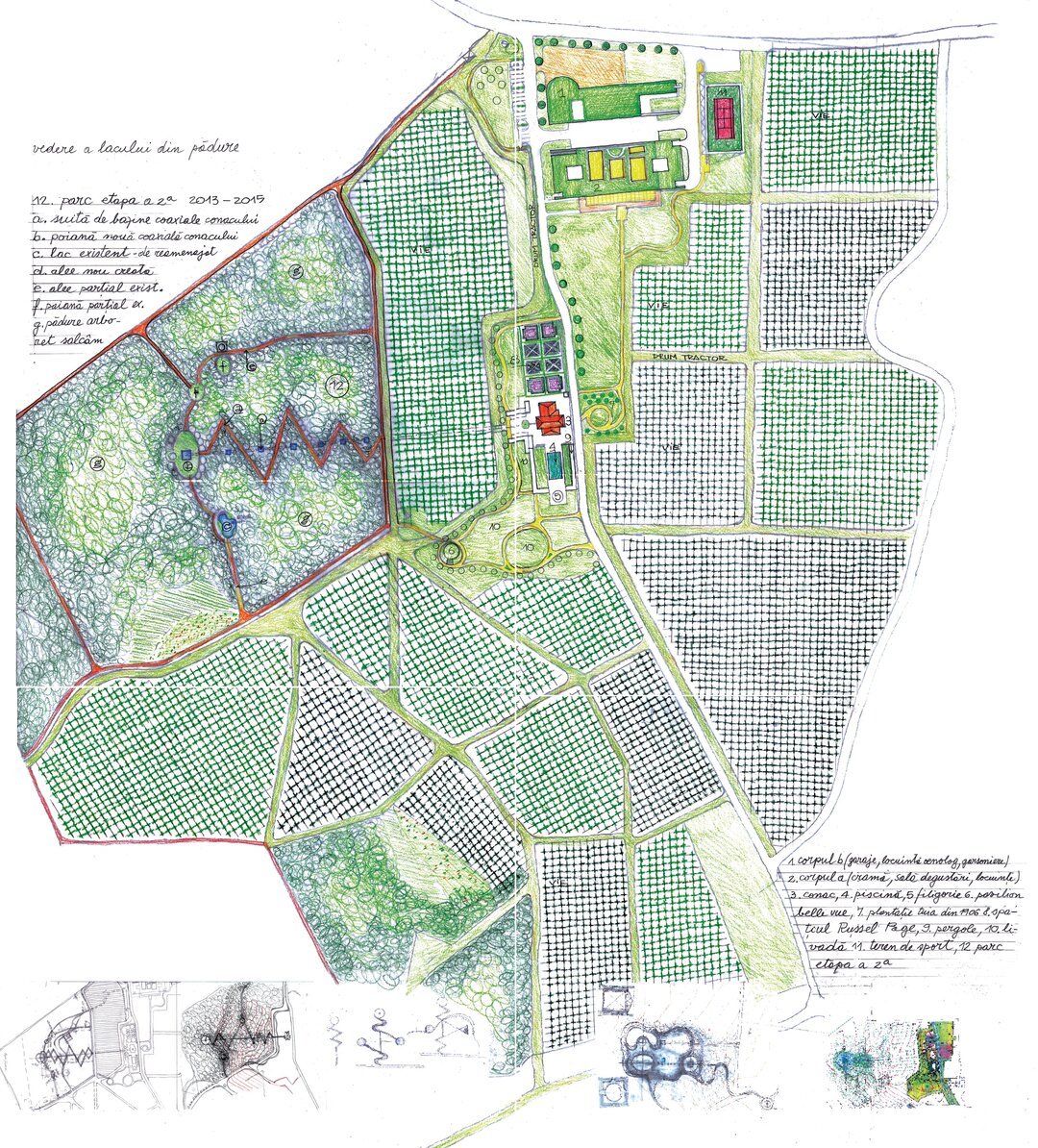

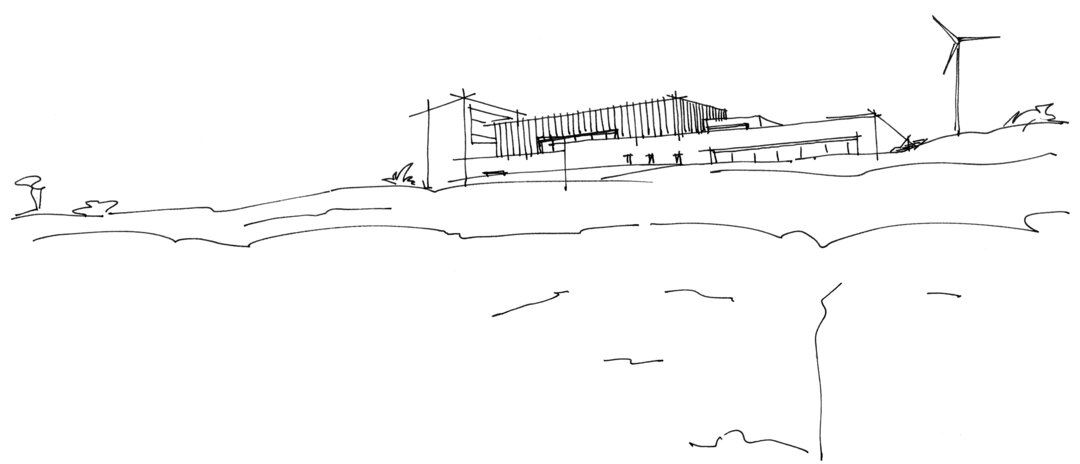

In the USSR, Georgia was the second wine-producing republic after Moldova. Independent for three decades, Georgia is struggling with its Soviet past and its legacies. The wine tradition has become a mark of identity and national pride. Part of the country's tourism is based on this very wine tradition, and in many of Georgia's vineyards, wineries have sprung up specifically designed for tourism. Most of them have a rustic feel, but in 2019, a winery project proposed by X-Arhitecture, with offices in Tbilisi and London, caught the attention of the internet and architectural publications with its perfectly contemporary lines. Designed for the Shilda Winery, it bears the name "Three Hills" and is truly interesting in the way its contemporary lines capture the core of the Georgian wine tradition. The winery is also to be built in the Alazani valley, very close to the Alaverdi monastery. It comprises three buildings, one for wine production and storage, another for wine tasting, and a third for organizing wine workshops. The buildings are semi-underground, as befits any winery that doesn't want to break with tradition. Seen from the back, they look like three hills because the rows of vines climb continuously up the roofs of the three buildings. Seen from the front, the buildings signify three curves rising out of the vineyard landscape and have been designed with the standard distance of 2.5 meters between the rows of vines in mind. The organic blending of landscape and building is beautifully continued in functional terms - to keep the interior temperature constant, the air-conditioning system will use the thermal groundwater, abundant in Kakheti, from the basement.

It may well be that the story of the wine is even older than 8,000 years and leads to places other than the Caucasus. Noah took vine cuttings with him on his ship, and as elliptical as the biblical text is, we understand that he knew how to plant them and how to make wine, which perhaps means that people before Noah also drank wine, although the Bible says nothing about it. For now all roads and evidence point to the land between the Black Sea and the Caspian. I'm almost certain that the thesis of the origin of the grapevine in the foothills of the Caucasus is true. Nowhere in the countries where I have traveled and where wine is a central part of the culture, in Spain or Italy, have I encountered a wine religion as in Georgia, which so naturally descends from history and monastery frescoes into the most mundane aspects of everyday life. Nowhere, such an attachment to the grape-fermented elixir. Georgia has the strongest wine religion of any country in the world. For Georgians, wine is God.

Georgians say Gaumarjos!, which means "Cheers!". In their language, the word is related to the noun "victory". For the whole of mankind, the discovery of wine by a prehistoric peasant from Kakheti, who accidentally left some grapes in a clay pot, was a great, decisive victory for everything that followed in the course of mankind.

Selected bibliography:

Giorgi Barisashvili, Georgian Culture of Winemaking, Artanjuli, 2022

David Lordkipanidze, Georgia, The Cradle of Viticulture, Georgian National Museum, Tbilisi, 2017

--17387-xl.jpg)