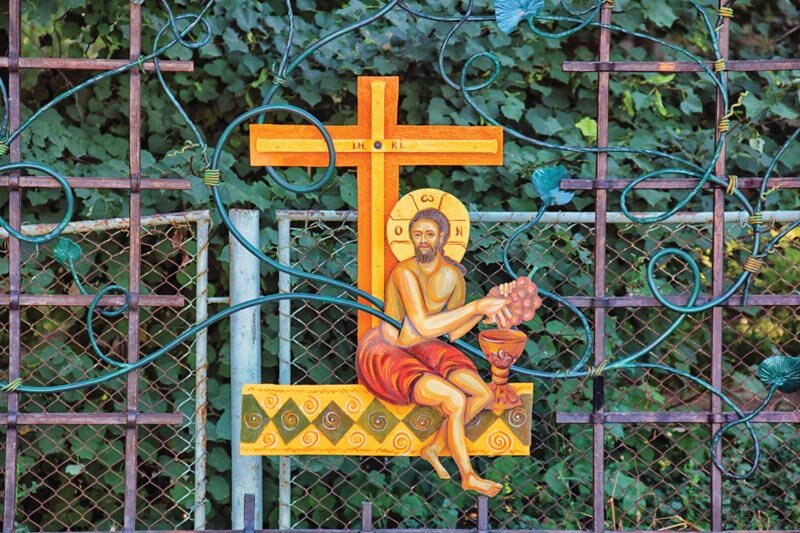

MATERIALITY = material + its immateriality = LOVE

I. The architect, between spirit and matter

During the Renaissance, architecture is said to have made the transition from a practical, manual activity to a spiritual, abstract preoccupation. It would have gone, as it were, from simple ontic gesture to gnoseologically enlightened creation. From an innocent craft, organically connected to spontaneous needs and possibilities, it would be promoted in just a few decades to the rank of an art with intellectual accreditation and a discipline of study.

More than with architecture, it was so with the other arts, once they were all grounded in theory. Their professionals - painters, silversmiths or sculptors - worked in their workshops, only after working with the material they would clean their hands of paints, acids or marble dust to go and participate in the debates of scholars and poets. Before long, they were receiving scholarships to Rome and reading treatises.

Only the architects were not dirty on their hands, did not work with raw materials or tools, and in fact did not even exist. They appeared suddenly in the debates, from everywhere and nowhere, that is to say, without being drawn from any particular craft workshop. They did not emancipate themselves from bricklayers, carpenters, stonemasons, diggers or painters. They were formed from scholars, imaginative men and intelligent managers. Architects were born intellectuals.

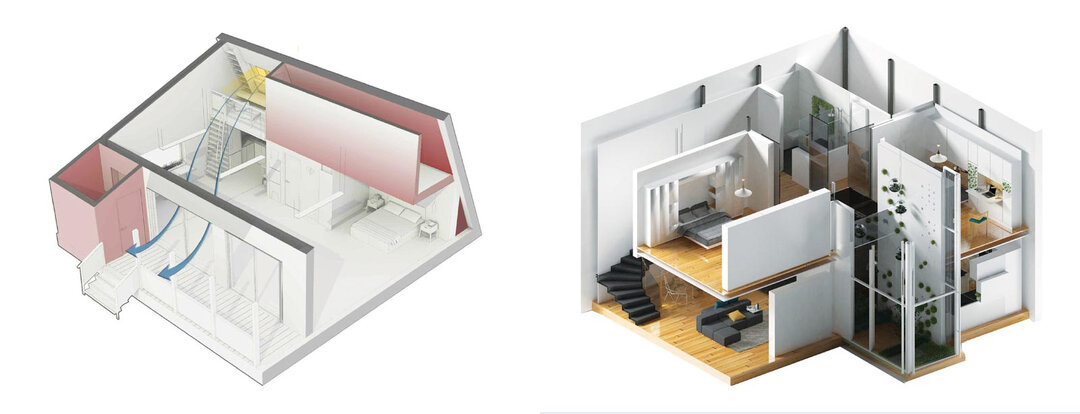

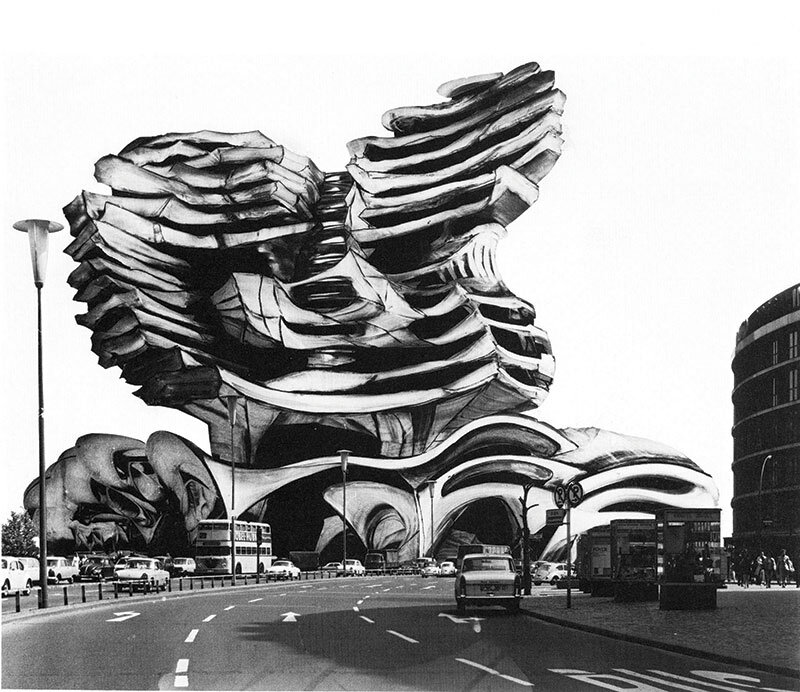

Thus, Renaissance architects were scholars and artists with books. They had never worked directly with building materials, had never cut and shaped them with their own hands, but knew them more by observation, judgment, and learning. [Things had not been very different up to that time either with Ichtinos, Vitruvius, or even with some of the builders of medieval cathedrals. Ingres' painting Pindar and Ictinus (sic!) shows the poet alone, raising his lyre, and we suspect that this was a source of inspiration for the architect]. So, as they had never directly experienced the condition of homo faber of the building, architects were always tempted to conceptualize rather than materialize. They preferred to work in the immaterial. Jonathan Hill said that sometimes the constructed building is not even the best place to explore architectural ideas, but rather the architect's drawings, study models and texts1. If architecture is, in fact, a metaphor, as Derrida put it, then it is clear that its favorite object is the hidden term of metaphor and not the signifier.

This explains architects' appetite for writing, debate and polemics, compared to painters and sculptors, who have not ventured too far into conveying ideas through words. (Paradoxically, architectural theory and criticism evolved much more slowly than art theory and criticism, but that's another story.) Christof Thoenes said that Alberti could never have become a good painter or sculptor because he was a man of the library, with no apprenticeship in any craft, but he managed to become one of the greatest architects of his time2.

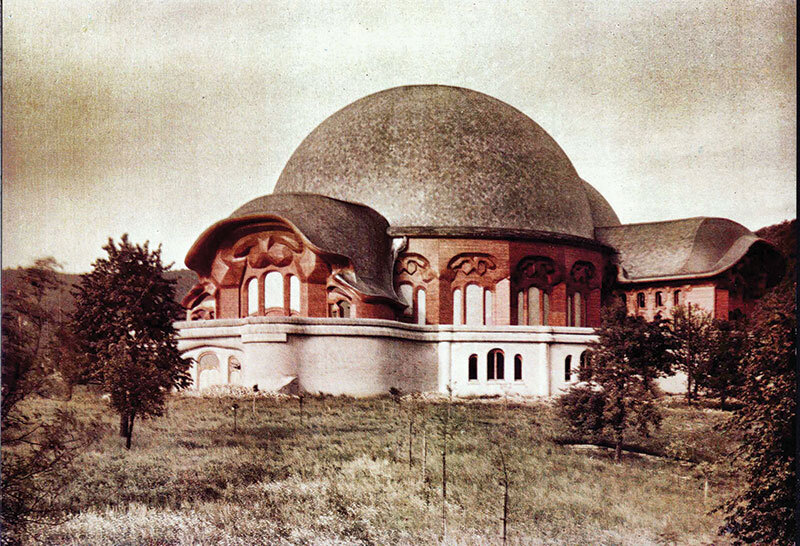

That architects seem to have been even more disinterested in the materiality of architecture since the Renaissance is shown by their designs, which contain no indication of materials or technical details. The drawings were beautiful, showing plans and facades to scale, carefully proportioned, dimensioned, with beautifully rendered ornaments and so on. They led you to believe that they could have been built from anything, stone, earth beaten with a corn or marshmallow paste. Boullée never told us what material he envisioned his fabulous cenotaph out of, although it was a problem and he was a serious practitioner; he was head in the clouds, but also down to earth, and he certainly had a realistic solution in mind, but he didn't feel it was appropriate to communicate it. The important thing was to define the cenotaph's immateriality. Life took care of the rest.

And it took care of it well, because the architects' apparent lack of interest in the physical constitution of buildings did not reflect negatively on their quality. The truth is that there was no need for more involvement, nor for more instructions and explanations, because there was still that old-fashioned appropriateness between form and material. In fact, the representation suggested it, because the shapes, dimensions and proportions were thought out in relation to the materials and construction possibilities that everyone knew. Besides, the options were limited - brick, stone, wood. Moreover, they were limited to what was local, as Vitruvius had recommended. They were the architects maniacs of composition, but even life wouldn't allow them to be eccentric. Even then, between designer, manufacturer, carrier and contractor, there was still the familiar agreement: local materials were brought in and processed using traditional techniques. Only the big investments benefited from special materials, brought in from who knows where and paid dearly.

The peace and unanimity between form and material, and between architects, lasted until Father Marc Antoine Laugier wrote down the idea of 'constructive truth'. In 1753 his idea was a remarkable dissent from the glory of spectacular form. He awakened the theoretical concern for the material dimension of architecture, invoking, after Vitruvius and before Gottfried Semper, the substantial and static rationality of the primordial hut. This new axiological coordinate of architecture - truth - which could only be realized with appropriate materials and in tectonic logic, was to become the growing obsession of the next two centuries and the foundation of Western aesthetics.

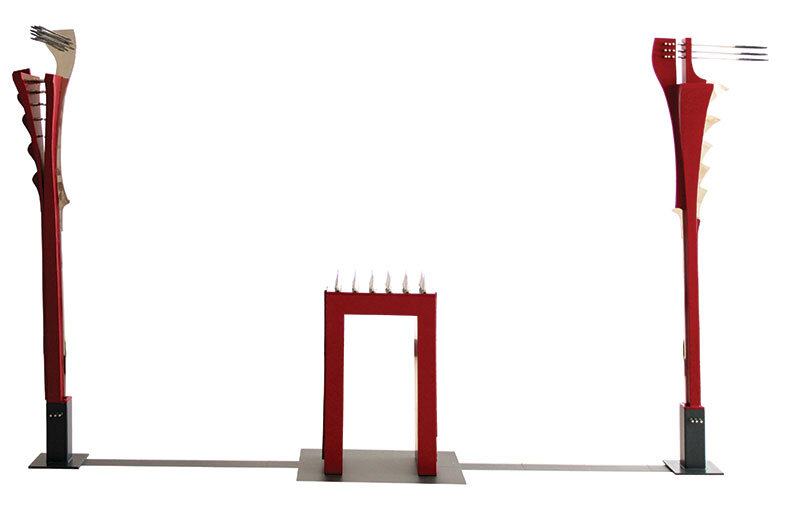

Soon the game of the two dichotomous approaches to architecture was afoot: those that invented its abstract qualities and those that revealed its physical qualities. While the Renaissance was discovering the nobility of form in light, the Neo-Gothic and Arts & Crafts were phenomenologically understanding the physical nature of construction. The binomial has gone by all sorts of names: matter vs. value (Kant), matter vs. form (Hegel), concrete vs. abstract, Pugin vs. Nash, neo-Gothic vs. neoclassical, romanticism vs. classicism (Schlegel), matter vs. spirit (also Hegel), matter vs. content (Marx)3. The game was to continue, also with different nuances: sensorial vs conceptual, substantiality vs formality (Heidegger), tectonics vs ephemerality (Frampton), materiality vs image, enveloping vs space, materiality vs immateriality (Jonathan Hill), Zumthor and Herzog&De Meuron vs Eisenman and Koolhaas.

Read the full text in issue 3 / 2015 of Arhitectura Magazine

NOTES:

1 Jonathan Hill, Immaterial Architecture, Routledge, 2006.

2 An observation also commented on by Christof Thoenes in the introduction to Architectural Theory. From the Renaissance to the Present, Cologne: Taschen, 2003.

3 Form is related to conceptual content.