Hammering the iron at the manor! – the “art of”

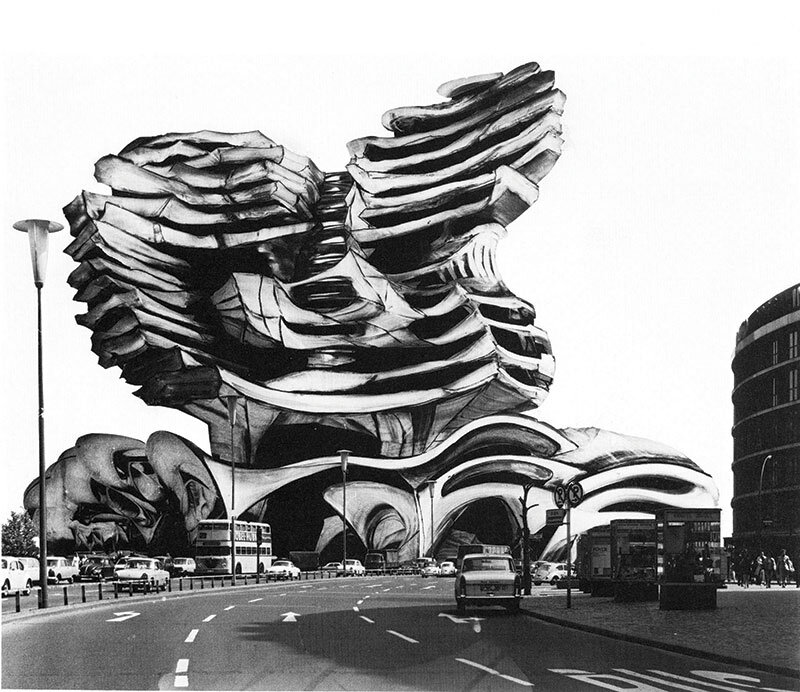

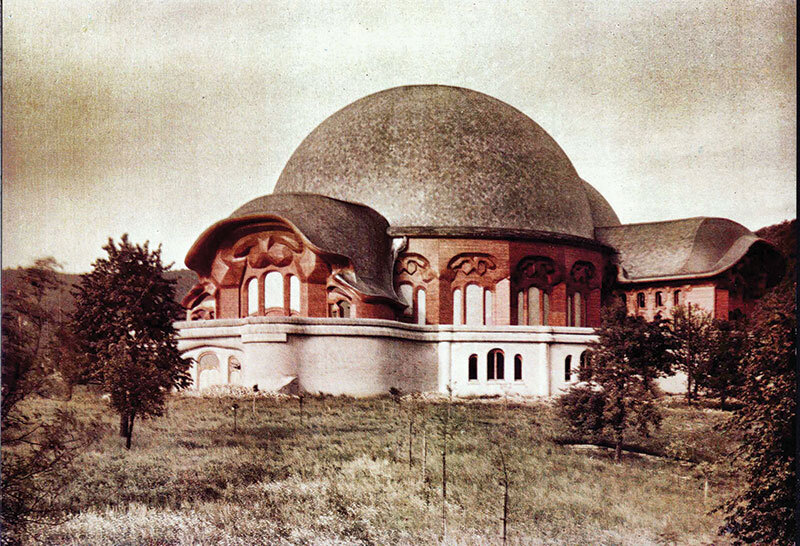

The workshop on traditional crafts and experimental techniques "Iron in the manor house!" aims to give local people, students and professionals in fields related to architecture the opportunity to get in touch with blacksmithing, fresco, traditional lime, clay and dung plastering, straw bale thermal insulation, stove making, vegetable weaving and pottery. The setting is attractive because the building site has a 'life of its own', requiring you to take decisions at a certain speed and therefore to leave your mark. The setting of the site is enriched by the context - the fact that you are in a historic monument, the Petre P. Carp mansion, with its own stories and visions for the future.

If the workshops vary each year, we can say that a constant, unformulated preoccupation of the workshop has been about the materials, their neighborhoods, the atmosphere they create. We generated and tested formulas, experimented with dosages and modes of application. In relation to these, we were interested, without making a programmatic plan, in their diversity and particularities, in training manual skills, in the possibility of reinvigoration through unexpected combinations. Changing the perception of the material, educating the community by example and training people, using local resources (people and raw materials), training and creating jobs for local people in connection with certain materials or ways of making or processing, involving the life of the material, were other priorities. I will recount some relevant attitudes without any claim to exhaustiveness.

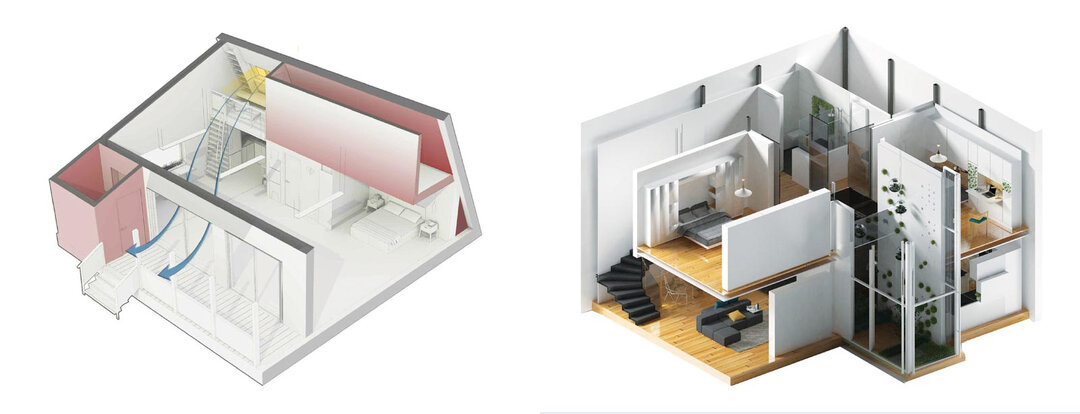

If a manor-house, the most important building in the village, ends up covered in plaster of clay and manure after having been brutally and excessively plastered, it is also to set an example in the village and establish that clay, in this case clay, is not exactly a worthless material, a stigma of poverty. Our stake was to copy this practice from the manor house to the houses in the village, as the ultimate goal of the project is not to restore a building, but a community. In terms of traditional plastering, we set out to learn the steps to follow in order to obtain a good quality clay plaster under the guidance of local craftsmen. Team members prepare the necessary materials and carry out a series of experiments using different amounts of water, clay and sand. Participants are familiarized with different ways of application and stratigraphies depending on the final purpose. As a result of these exercises, they arrive at a dosage of the three materials whereby the resulting plastered surface is smooth, without cracks. Along with the frescoes executed according to the usual practices, last year saw the first fresco executed on a dung support; we tension the glass on a wrought iron skeleton; the thermal insulation is executed with straw bales and a clay bed, and we try inserting the metal plaster into the clay plaster.

We are wondering whether a wrought-iron bracelet can still be agreeable nowadays, and whether two or three accents given by the insertion of colored spherical stones can sufficiently ennoble the material so that you can find it on ladies' hands. The clay-plastered bathroom houses a glazed and silken bath-tub inside, but rusted on the outside. Above it, a wrought-iron frame holds a curtain through which the light passes, and the whole ensemble takes on the feel of a yurt in a barren landscape. The concrete slabs that line the floors of the ground-floor rooms are polished and look like well-crushed stones that have been trodden for decades. The perimeters of the gravel-filled rooms break the rigidity of the floors. The "experiment house", as architect Șerban Sturdza sometimes calls it, is a lesson in courage and "derigidization", in living use.

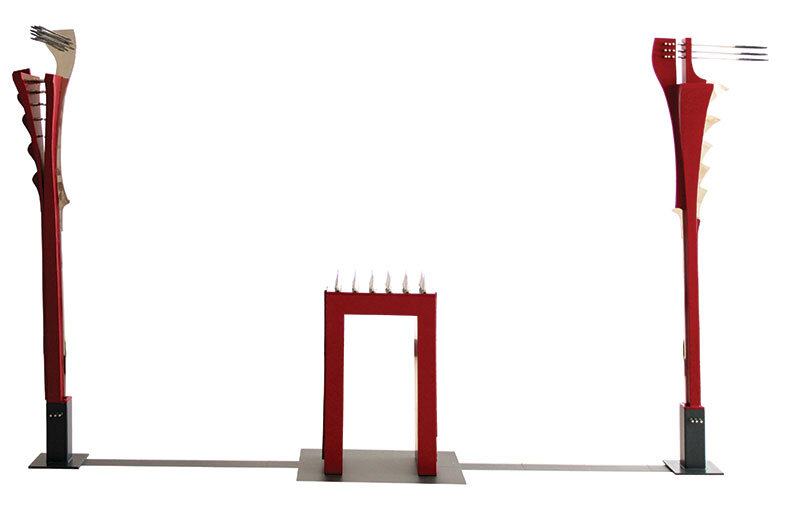

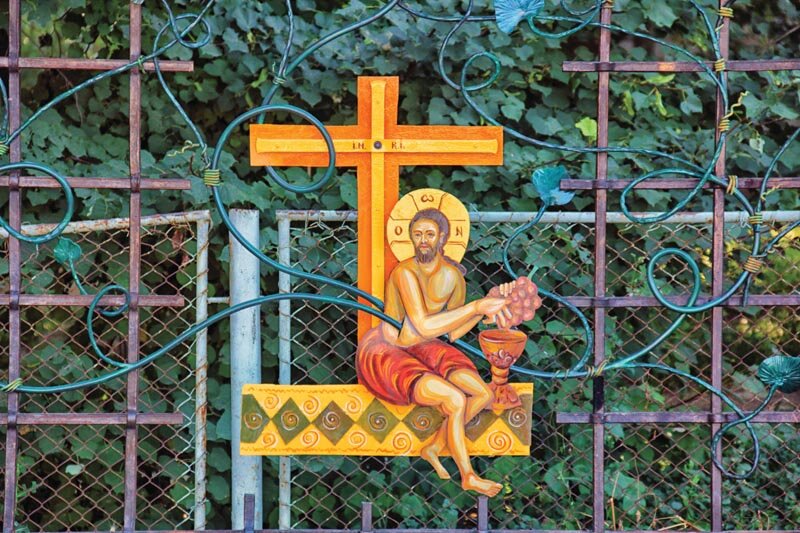

The bus stop in Țibănești is an art object of public interest, located in the center of the village and created as part of the 6th edition of the Blacksmiths' Festival, the workshop "Batem Batem Ironul la Conac! It was executed on the basis of a partnership between the Association "Maria" from Țibănești and the Administration of the National Cultural Fund through the cultural project "Transfer of innovation - ironwork of art", with the support of the Municipality of Țibănești and aimed at realizing a bus stop for the commune. The work was carried out using traditional wrought-iron techniques in the blacksmith's workshop in the village of Țibănești. The work teams, made up of students from the "Petre P. Carp" Technological High School and workshop participants, were guided by blacksmiths from the Republic of Moldova and France. On June 29, the commune's birthday, the station was inaugurated by the local authorities in the presence of the mayor.

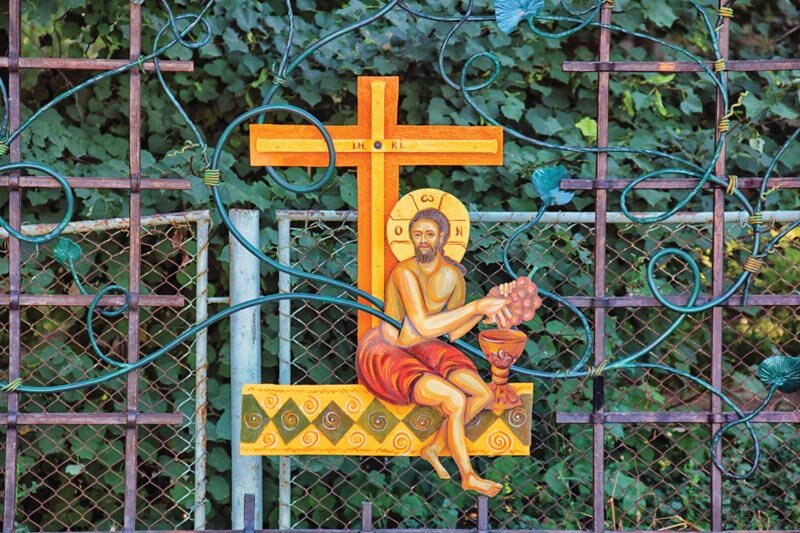

Despite the fact that it is an object of community interest, the bus stop was also designed and built not to be vandalized - this is the reason for the Christ, placed at the level of the man sitting on the bench, as if the two were communicating. The image was taken and interpreted from an old peasant icon "Jesus - vine", the idea of such an insertion came after realizing that there are many practicing Christians in the community. The plain sheet metal from which Christ was made, cut in the blacksmith's shop, was painted by fresco painters. The result of the blacksmith shop, the bus stop, questionable in places (due to the use of polycarbonate awning and biscuit pavers provided by the city council), is, however, proving to have a great impact on the community. The smithy gains local prestige, children become 'craftsmen' and each year the project is enriched with forged leaves, which gradually create a canopy and replace the polycarbonate, while doing away with what seemed fatal to the coherence of the original intention. The bus stop is an object whose course and consequences are more important than the construction itself, with all that an architectural object implies. The realization of the bus stop brings with it a palpable sense of increased urban comfort and civic awareness. The project did not come out of nowhere, but was heralded by a series of smaller-scale actions: the realization of a candle-holder for the All Saints' Sunday Church, the cross near the Carp family mausoleum and the chandelier at the Carp mansion, as part of the Street Delivery festival.

Also in Țibănești, Saints Peter and Paul have been painted on two round wooden shredders with tails. The result is encouraging, and the original use of the wood is so lost that many visitors no longer recognize its origin. With projects like this, using sheet metal, fence paint and, why not, shredders, we have discovered the value of simple or overlooked materials that can offer more than we might have expected. Ironwork walls have a particular materiality. Initially used as a medium of communication through drawing between Romanian students and French blacksmiths, then as a small personalized bilingual dictionary, the walls have been filled with "beliefs", projects or quotes written in charcoal, and the smooth appearance has been replaced with the richness of a true graffiti-like, textured research, which loses its flatness through hanging tools or other artifices.

At the mansion, materials are tried with the hand, with the body, clay is pounded with the foot, the hammer leaves marks in the palm, iron is pounded with sweat - only in this way can one assume materials and break out of the formalism of a drawing on paper or made on a computer. By experiencing direct contact with the materials, you realize how complex the consequences of a line can really be, you understand the whole path and you become more responsible for the sheet of paper, for yourself and for the potential recipient and user.

The life of the material that is used in the construction process is important: how many families eat working with it, how many children play with it, where does the raw material come from? Do they pay a fair price for the potter's pots? All these questions also entail a responsibility that we have to take towards those who work it and mold it into an object with individual characteristics. In the workshops at the manor we have learned not to look for universally valid recipes and formulas, but to judge each case on its own, how important it is to use a material in its context, to work it correctly and with its properties in mind, letting our hands imprint it and fill it with content.