Thematic Dossier-Industrial Archaeology

ARGUMENT

Industrial ruins,

between poetics of memory and archaeology

The topos of ruins, vigorously implanted in the poetic imaginary since the pre-romanticism of the 18th century, introduces a distinct touch of melancholy in European culture. All European Romantic poetry deals in one form or another with this theme of ruins, of dilapidated, time-worn spaces, silent but meaningful witnesses to bygone times. A pretext to meditate on the ephemeral dimensions of man in the universe, on his evolution under the ascendancy of time. For the Romantic, the ruin was an allegory of his own existence.

The poetry of ruins is back in fashion. An attraction to decrepitude, to abandoned places, overgrown with spontaneous vegetation, as a metaphor for freedom, is in the air. We paint the cobblestones, we rejoice at the sight of an unfinished wall, rough, rough and frustrated, with the brick layers showing through. It urges us to dream. If real ruins are not at hand, we fabricate them, reinvent them, mimic abandonment: apparent concrete walls, as revealed by the deco, scratched paintwork and artificially blackened walls. The destroy-vintage ambience is all the rage, seductive for bobo-nomads, a kind of urban hipster explorers, half bourgeois, half bohemian, for whom rehabilitation means not restoring anything but controlling decrepitude, preserving the wounds of time, creating configurations outside the norm and inventing new ways of living.

Françoise Choay, in The Allegory of Heritage, dates the emergence of ruins from the proto-Renaissance (11th-12th centuries), which is distinguished by an antiquizing interest in the ruins of classical Rome, then abandoned and overgrown with wild vegetation or inhabited (the arches of the Colosseum were colonized by dwellings, workshops, warehouses, like the Circus Maximus or Pompeii's theatre, occupied by merchants or taverns). A more general and organized interest in ruins reveals itself in the Quattrocento. A new gaze "transformed ancient buildings into objects of reflection and contemplation"1 (F. Choay).

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the perspective shifted perceptibly: the taste for ruins extended beyond the classical, to all eras and all types of building. This is probably a corollary of the period's taste for the exotic and the tendency towards historical relativism.

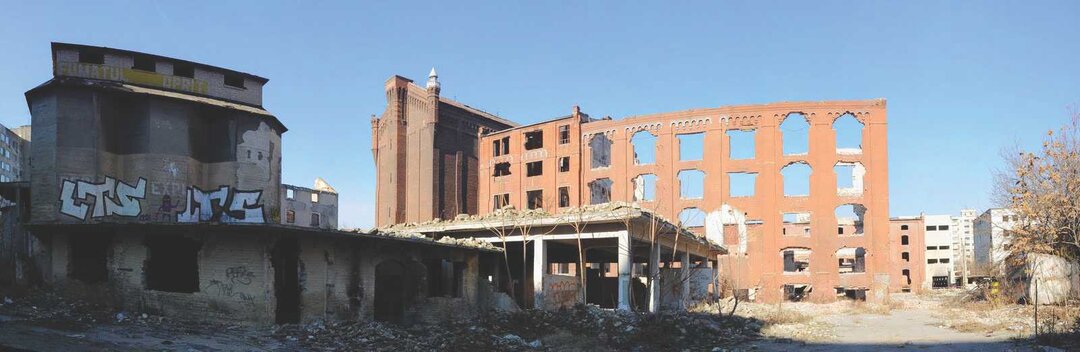

Ruin is valuable because it stimulates reverie and meditation. But does this also apply to the ruins of the 'temples' and 'cathedrals' of the industrial revolution? How can a dilapidated, blackened and filthy industrial hall, drowning in piles of rubble and heaps of machinery and scrap metal, be conducive to reverie? What's the difference between Cârța and Assan's Mill? In the skies of both you can see the stars...

Mircea Cărtărescu seems to have fully understood the lyrical and mnemonic potential of industrial ruins. He evokes, in his fabulous writings, the old street-keeper of his childhood, the Dâmbovița Mill (unfortunately demolished), the 'bread castle' that became a mythological character, a symbolic landmark on the mental map of the city for the child Mircea and a recurring motif in the work of the writer who was to be.

"Its pediment, with a large circular opening in the middle, still towered, in the racursiu, above the fragile model of the neighborhood, so high and so melancholic that, especially in the summers, when the clouds from the sparkling sky crossed the great rosette, the construction tightened your heart, made you feel more than ever your loneliness.

Like the water tower on the roundabout where tram 21 used to turn, like so many depots, warehouses, covered squares, disused factories, steam mills and gas tanks in our twilight city, the industrial architecture of the old factory was paradoxical and fascinating, for the massive walls, smooth, functional, from which protruded the heads of metal ramps, full of bolts, the light-scraped windows, made of thick, bubbled glass, the reliefs and friezes that served to increase the resistance of the heavy volumes, were improbably, absurdly, touchingly, somehow improbably [...], with cheap stucco ornaments, grotesque and useless, born of the frustrated aesthetics of a century as refined and heroic as it was languid and dreamy."

* * *

It is no coincidence that the industrial heritage movement has its origins in the cradle of the industrial revolution in 1950s England, following the destruction of many factories during the Second World War. With the advent of the term 'industrial archaeology' in 1955, attributed to the British historian Kenneth Hudson, the process of revalorizing industrial ruins has gained momentum.

In the 1960s and 1970s, with the emergence of national cultural heritage movements, industrial archaeology developed as a distinct form of archaeology with a strong focus on conservation and protection, first in the UK, then in the United States and other parts of the world. It was during this period that national inventories of industrial heritage began to be organized (in England, the Industrial Monuments Survey, and in the USA, the Historic American Engineering Record). Several national and regional industrial archaeology organizations were established: the Society for Industrial Archaeology (North American-influenced) in 1971 and the Association for Industrial Archaeology (English-influenced) in 1973. Also in 1973 the first International Conference on the Conservation of Industrial Monuments was held at Ironbridge in Shropshire. This conference made an important contribution to the establishment in 1978 of The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH), a worldwide organization for the promotion of industrial heritage, which also produced an Industrial Heritage Charter in 2003 at the 12th International Congress of TICCIH in Moscow.

A definition of industrial archaeology, which is quite close to what it means in practice,

is the one given by the Smithsonian Institution Archives Center in 2001: "Industrial archaeologists study and survey industrial sites and structures, document them without dislodging artifacts, and encourage their preservation or adaptive reuse. In addition to their own specific work, industrial archaeologists consult other sources to gain a better understanding of the period under study, aspects of the industry and technology of the time. To bring the site to life and place it in a human and industrial context, they interview former workers, visit industrial sites that are still in operation, examine museum collections, study old photographs, memoirs, correspondence, registers of former enterprises, and other publications.

The objects of study of industrial archaeology are generally all artifacts

related to the industrial era, but in particular: old docks and port warehouses, mills, textile factories, steel mills, canals, bridges, mines and railroad systems. Industrial archaeology has traditionally been the preserve of archaeologists, engineers, architects, historians, historians, artists and, more recently, economists, sociologists and anthropologists.

Over the last twenty years, two more or less independent sub-branches have emerged from the main branch of industrial archaeology: commercial archaeology and social archaeology. While the distinction between industrial and commercial archaeology is made by the object of study (commercial archaeology studies buildings, artifacts, structures, signs and symbols of 20th century trade), industrial and social archaeology (which deals with

studies of the lives of workers in industrial areas or investigates unusual events in the same area of interest), the boundaries are at best unstable, with social archaeology being assimilated to a research method that is proper to industrial archaeology.

* * *

In contrast to the Nordic countries and Great Britain, where the cultural value of industry has been recognized since the 1950s and is the subject of general adherence, in Romania, industrial vestiges still inspire contradictory feelings, from rejection to fascination and pride, to evocation of suffering.

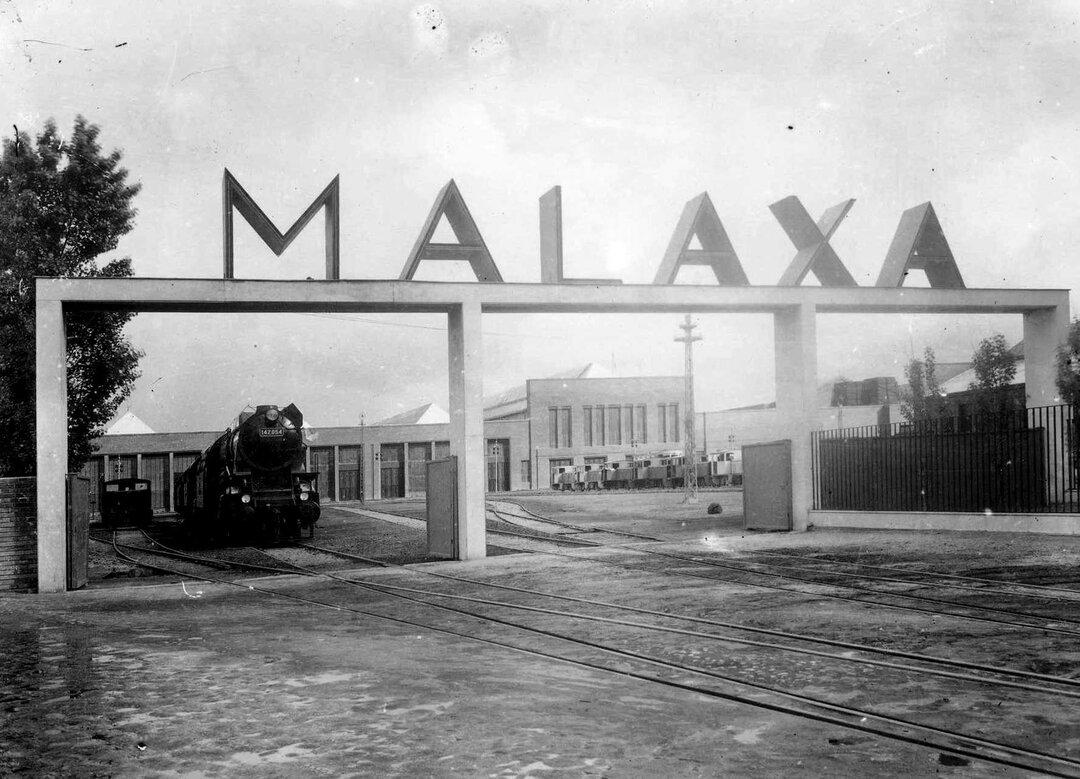

In the Romania of our times, industrial buildings and complexes have been and still are viewed with reluctance, especially by the generations that lived under communism, who consider them to be an expression of the dictatorship of the proletariat and the imperative of fulfilling the five-year plans. In the same way, industrial architecture is not seen as a field for the affirmation of professional talent. It is forgotten that communism did not invent industry and that many of the industrial buildings in which people worked under communism were built before the First World War and in the inter-war period. And that some of them had a particular architectural value, even if it was hidden under layers of dirt and placards praising the much-loved rulers. Of course, there were also some industrial-factory buildings of no architectural value whatsoever, but in the great mass of them one could distinguish factories and plants that had weathered earthquakes, wars and revolutions, with spectacular volumes and impeccable brickwork, with elaborate stuccowork ("plaster angels, now ciliated and decapitated, with yellowed wings.... crenellations, wreaths and masks, indentations running along the endless beams; a chlorotic plaster maiden... with her hair spilling over two stories over the broken brick of the walls; a philosopher in a toga, holding an unknown instrument in his hands"), places marked by the lives of the people who had worked and lived within their walls.

The nationalization of the means of production after 1945 was a disaster, not only for the country's population, but also for Romania's industrial heritage. Respect for property was replaced by a lack of responsibility, and the workplace was assimilated to coercion. The negligence, carelessness and ignorance encouraged by state policy have condemned a large part of Romania's industrial heritage to demolition since the 90s.

Those who reacted first, who had eyes to see, a clear mind and enough sensitivity to feel the spirit of these places, the latent life within the walls of these vestiges, were the young people we might call the forerunners of today's urban explorers. They bribed porters to enter industrial premises doomed to demolition, to explore and take photographs, creating a priceless collection of images (often, unfortunately, all that is left of the exemplary buildings of the industrial world). The virtual environment was gradually taken over by thematic blogs, small associations sprang up. In the early 2000s, specialists took over. Our late Professor Sanda Voiculescu was enthusiastic about what could be done in the field of industrial heritage rehabilitation. She had her sights set on the reconstruction of the Uranus neighborhood, which was particularly dear to her heart. In fact, one of his latest works is the historical study of the former Bragadiru brewery. A complete study through the multi-criterial prism of industrial archaeology is the one conducted by the architect Hanna Derer on

The "C. & S. Schiel" paper factory in Busteni.

Mention should also be made here of the 5 international industrial archaeology workshops coordinated by the architect Irina Iamandescu from the Ministry of Culture, through which specialists from the international organization TICCIH (International Committee for the Conservation of Industrial Heritage) were able to get to know Romania's industrial heritage, which they considered to be particularly complex and valuable. Real estate investors still need to be convinced, for whom the land beneath these buildings needs to be speculated as much as possible.

* * *

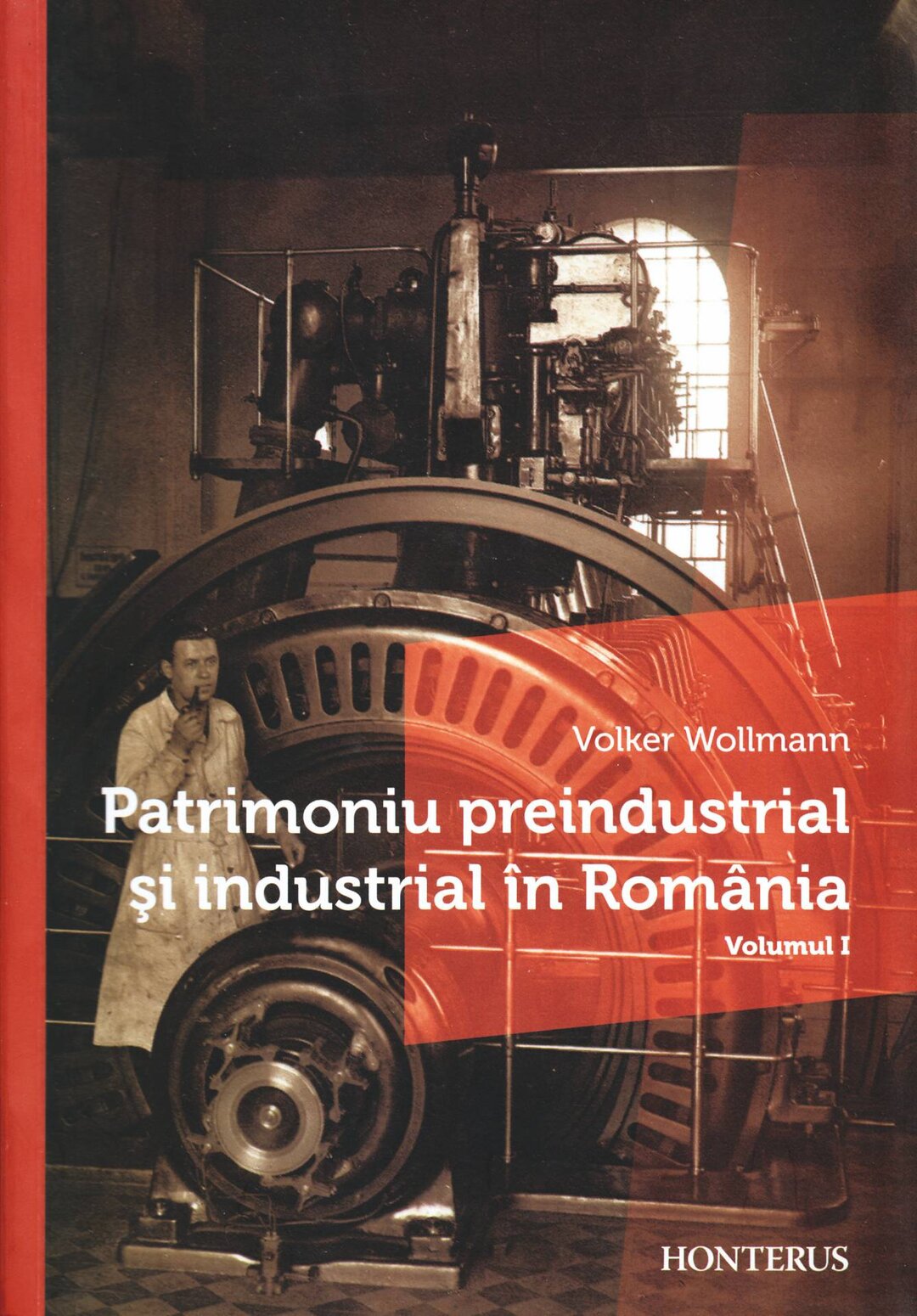

The thematic dossier of this issue dedicated to Industrial Archaeology brings up several aspects of this field which is still insufficiently explored and exploited in our country.

The Charter of Industrial Heritage - adopted by TICCIH (the International Committee for the Conservation of Industrial Heritage and the specialized advisor to ICOMOS - the International Council on Monuments and Sites - on industrial heritage) at its congress in Moscow/Nizhny Tagil in 2003, is a reference document for the field of industrial archaeology, which defines the basic terms around which a whole specific terminology - Industrial Heritage, Industrial Archaeology - has been structured, and also fixes the historical period of main interest, from the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, i.e. the second half of the 18th century, to the present day, without neglecting its pre-industrial and proto-industrial roots.

Ioana Irina Iamandescu discusses the importance of inventorying Romania's industrial heritage. The article reviews the attempts at inventorying historical monuments since the 1950s and, in particular, in the last 10 years, advocating the correlation of partial inventories carried out with the collaboration of certified specialists in the field of monument protection with a revised methodology for classifying and inventorying historical monuments, in order to introduce the necessary elements for adapting the evaluation to the particularities of industrial monuments. This could pave the way for the creation of a specialized database, integrated into the inventory system of the National Heritage Institute, after the application of a specialized "filter".

The participation of the "Ion Mincu" University of Architecture and Urbanism in the early 1990s in the colloquia of the Eurocultures Association, Observatoires du développement Socioculturel de la Ville on the themes of the contemporary city and, since 1995, the problems of protection and conversion of Europe's rich industrial heritage, is an example of sustainable cooperation and partnership at European level. Within the framework of the Euromusées 2001 project, a database of dozens of abandoned or endangered industrial sites was elaborated and the idea of a distance training program for actors working in the field of industrial archaeology - Forcopar - was put forward. This was considered a very timely direction at a time when there was no distance training at European level for those wishing to specialize in this field of monument protection. Forcopar 1 was aimed at the "feasibility" of continuous distance training in industrial archaeology, and Forcopar 2 (2012-2014) was aimed at the "operational" aspect (Nicolae Lascu).

The issue of methods of classifying and representing post-industrial urban landscapes, materialities and socio-naturalness, subjects that are difficult to categorize and often evade conventional labeling, is the subject of the article by Liviu Chelcea, anthropologist, known for his work in the field of industrial heritage, author of the book Bucharest Postindustrial. Memorie, dezindustrializare și regenerare urban (Polirom, 2008). The landscape that has replaced the former industrial spaces in Bucharest shows a reticence towards the main narrative concepts frequently used in urban post-industrial sites around the world, such as return to nature, abandonment, real estate development, industrial heritage, creative industries or the rehabilitation of ruins. Instead of a standard history, the emerging ecologies of former industrial sites in Bucharest relate to a heterogeneous combination of fragments: planned and unplanned action, geological, human and biological forces, and destruction caused by nature and humans. The description of this unstable emergent ecology includes descriptions of the actors - predominantly human but also non-human - their actions and the materialities that populate such sites.

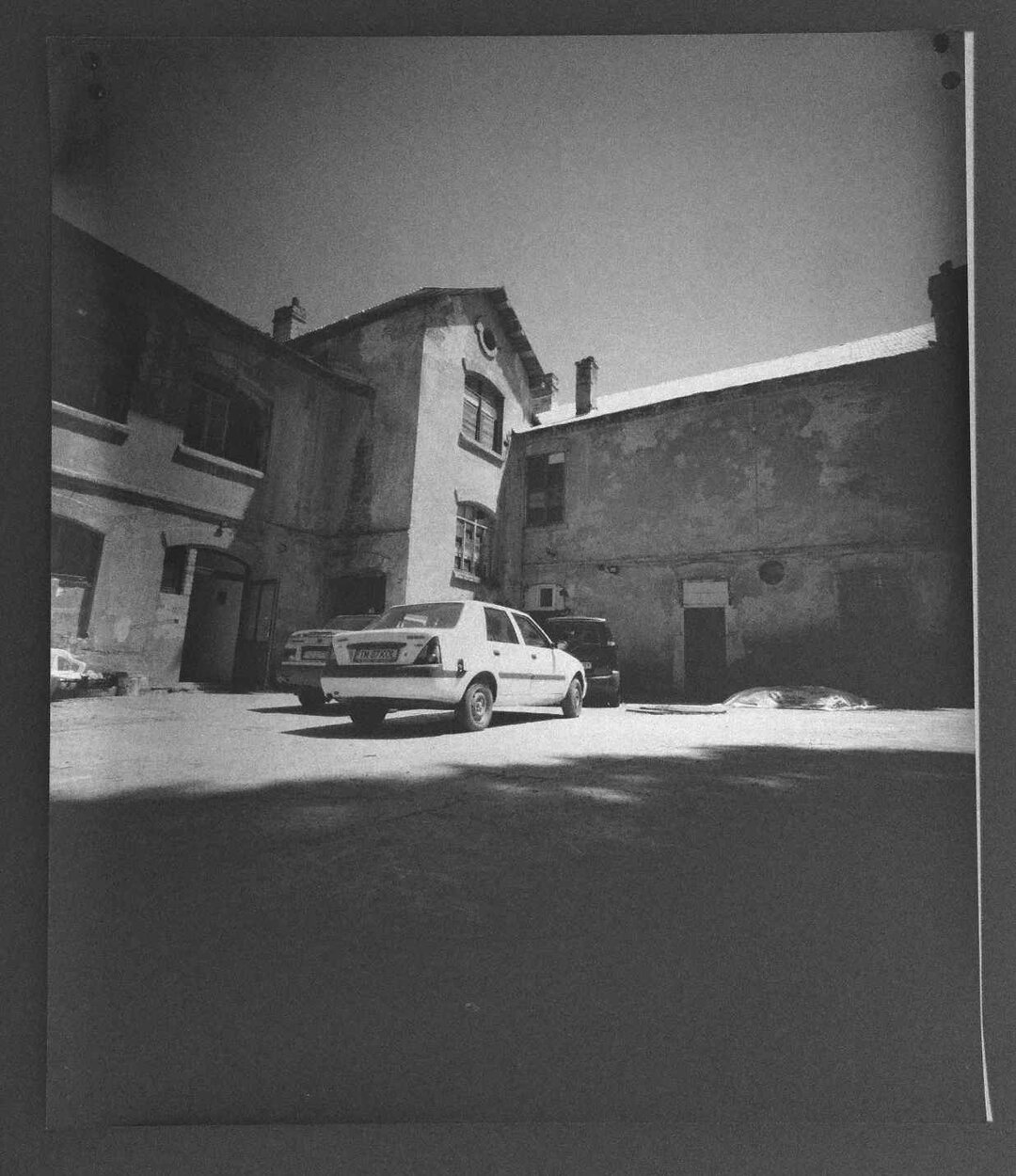

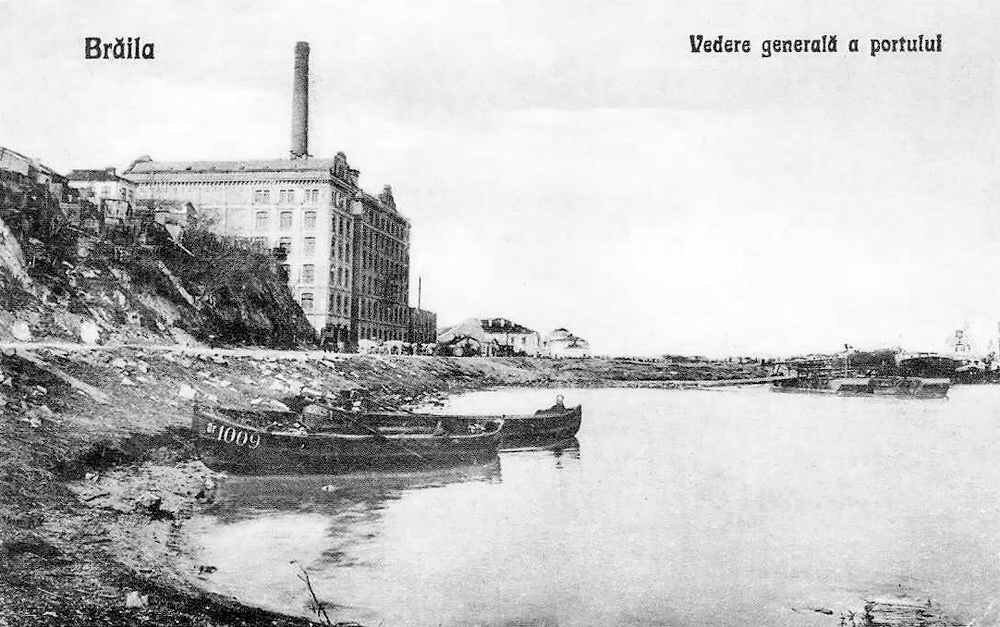

The dossier presents several examples of industrial buildings representative of the different approaches to industrial archaeology and the valorization of industrial heritage in Romania, advocating for the discovery and valorization of the cultural vocation of industrial architectural heritage: The Laminor Hall of the Malaxa Factories, author Horia Creangă, a landmark for the architecture of industrial buildings in Romania (Nicolae Lascu, Ruxandra Nemțeanu, Peter Marx, Niels Auner) and the CFR Grivița - GRIRO workshops (Sorin Gabrea) in Bucharest; Industrial heritage in Bucovina (Adrian Nicolae Cioangher) and the Waterworks in Suceava (Maria Mănescu); the abandoned mills of Braila (Maria Stoica).

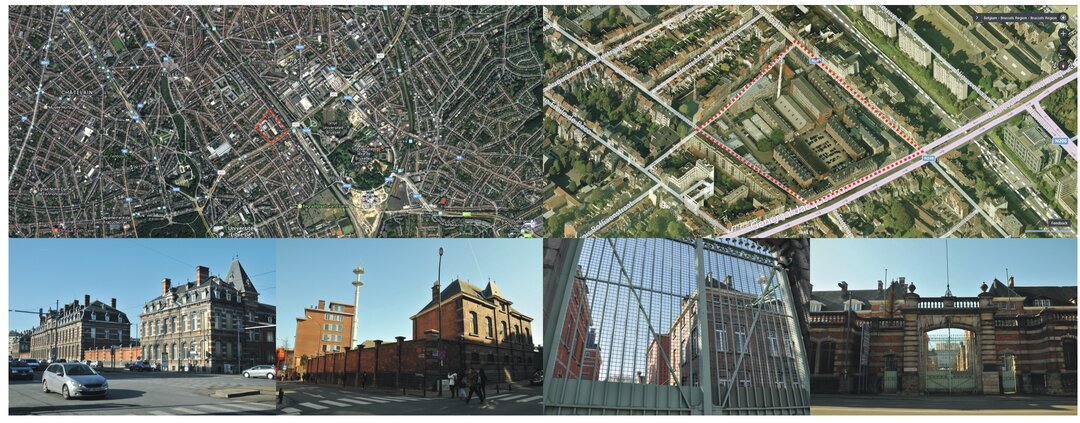

The examples from Romania are counterbalanced by the presentation of the project "Crown Barracks" - Brussels of the workshop "Urban conversion of industrial sites", specialized project year V, University of Architecture and Urbanism "Ion Mincu" Bucharest (2016-2017), an exercise proposed by Professor Francis Metzger (Faculty of Architecture "La Cambre-Horta" of the Free University of Brussels - ULB). The subject of the study was the conversion of the former "Royal Gendarmerie School" in Brussels of the Belgian Federal Police, the projects elaborated during the workshop practicing an approach that integrates the general concept, the character of the place, the urban strategy and the sustainability of the architectural intervention, situating the architectural approach in a natural continuation of the spirit of the place (Andrei Eugen Lakatos).

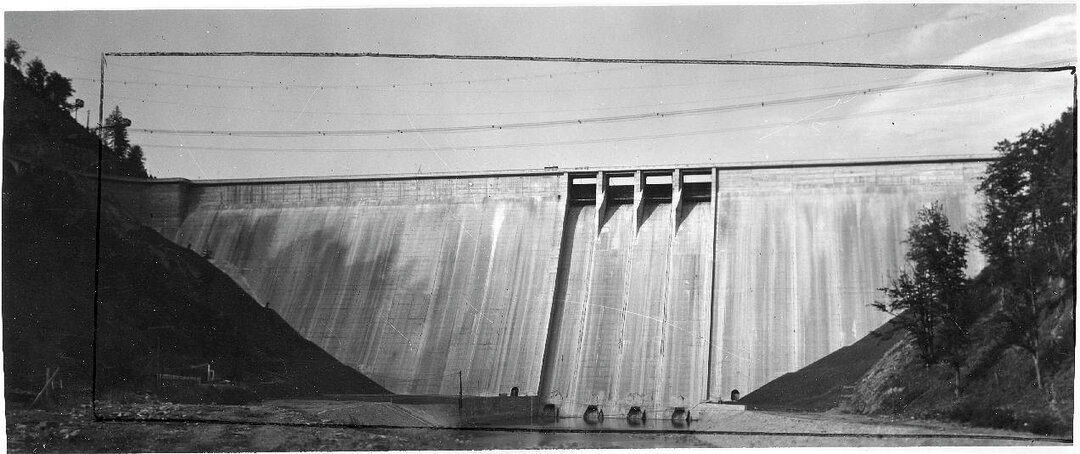

The thematic dossier is completed with a photographic documentary dedicated to the Bicaz hydroelectric power station, based on the photo archive of the Romanian Union of Architects, and a photo essay illustrating the use of exposed brick in several industrial buildings in Bucharest: Assan's mill, whose fate seems to be sealed, the water tower in the Drumul Taberei district, which originally served the nearby military unit, dismantled in the late 1960s with the systematization of the area (a long-lived kiosk has been operating on the ground floor of the tower since before 1989...!) and some successful examples of functional conversion (The Ark, a cluster of companies and independent organizations from the creative industries, the former Commodity Exchange - Customs warehouses; Metropolis Center, the former "Cartea Românească" workshops - "30 December" Polygraphic Printing Enterprise).

Finally, the presentation of the cultural project "Mina de idei Anina" (Oana Țiganea, Gabriela Pașcu) encourages us by revealing the enthusiastic approach of a team of young architects who have tried to truly understand the spirit of a place that at first sight is forgotten by the world. Initially conceived only as an interdisciplinary workshop to address the issue of post-industrial territorial revitalization through cultural tourism, the project came to life, continuing naturally through three years of repeated visits to Anina, supported by archival research and bibliographical documentation, photographic inventory of the territory, discussions with the local administration and the community, three industrial heritage workshops and a series of cultural events such as exhibitions, guided tours or video-mapping projections in the urban public space.

The subject is far from exhausted. More industrial monuments should have been mentioned, more projects should have been detailed. Unfortunately, the limited editorial space has put us in the unfortunate position of having to leave aside, perhaps in anticipation of a second issue on the subject, a series of articles that would have allowed us to extend the subject to a larger, territorial scale in the field of urban regeneration, a perspective that is particularly necessary in the case of large disused industrial sites.

The idea that we wanted to convey in compiling the dossier is the firm belief that the re-evaluation of industrial sites and industrial architectural objects through the prism of current functions, the patrimonialization of industry, can bring forgotten values and symbols to the forefront, and can be a powerful revealer of mentalities, with the potential to change them.

Of course, the options for reassessment are diverse, ranging from deep transformation, grafting, occupation of the site without heavy interventions, duplication. Whatever the architectural solution adopted, the industrial memory of the work can thus be preserved, inscribed in the history of the territory. Demolition should be a well-considered last resort.