Post-industrial ecologies: industrial debris, nature and the limits of representation

text: Liviu CHELCEA

Published in Parcours anthropologiques, 10 / -1, 186-201.

Introduction

The main issue addressed in this article concerns the methods of classifying and representing post-industrial urban landscapes, materialities and socio-naturalness, subjects that are difficult to categorize and often evade conventional labeling. If post-industrial spaces elude not only planned use, but also the dominance of a single unplanned function, how can they be described in order to construct a coherent representation? The landscape that has replaced Bucharest's former industrial spaces exhibits a reluctance to the main narrative concepts commonly used in urban post-industrial sites around the world, such as return to nature, abandonment, real estate development, industrial heritage, creative industries or the rehabilitation of ruins (Edensor, 2005; Bélanger, 2009; Millington, 2013; Moshenska, 2015). Instead of a standard history, the emerging ecologies of former industrial sites in Bucharest relate to a heterogeneous combination of fragments: planned and unplanned action, geological, human and biological forces, and destruction caused by nature and humans. But none of the elements is dominant. As we shall see in what follows, deindustrialization produces open spaces, exposed to change, with minimal internal consistency (Culescu, 2007:7). Describing this unstable emergent ecology includes describing the actors - predominantly human but also non-human - their actions and the materialities that populate such sites.

Bucharest underwent massive deindustrialization in the 1990s and 2000s, similar to many similar cities in Central and Eastern Europe (Marcinczak and Sagan, 2010; Ianoș et al., 2012; Mirea et al., 2012; Nikezić and Janković, 2012; Pozniak, 2013; Popescu, 2014; Grigori and Katchi, 2015; Jucu, 2015; Mulíćek, 2015). Despite the process of deindustrialization present continent-wide in most ex-socialist countries, the strictly utilitarian approach to urban nature, together with the entrepreneurial vision of urban life that has captured the imagination of local government, has camouflaged for many scholars the importance of such spaces in understanding cities, nature, values and urban metabolism (Gandy, 2013: 1301; Edensor, 2005). A summary comparison of census figures from 1899 and 2002 shows that the percentage of people employed in industry in Bucharest is identical (9%). At the peak of the real estate bubble in 2003-2008, of the 200 large factories in Bucharest, only about 33% were still active (Chelcea, 2008). 30% were still operating at reduced capacity, while 20% of them had been converted into rental and warehouse spaces. Finally, 33 of these factories were either completely inactive, had been demolished or a combination of both (Chelcea, 2008). The latter category is the subject of this article, although there are also comments on those still in operation or those that had been reduced to space. As factories go bankrupt or are awaiting modernization from the ten-year post-privatization period that forbade demolitions, they remain unexploited for hegemonic reasons, but generate a variety of eclectic uses and landscapes.

Although there are situations where a particular type of use becomes dominant, many post-industrial sites are characterized by an amalgam of uses. The four main uses we have identified in post-industrial spaces are (1) urban mining; (2) children's playgrounds; (3) shelters for marginalized beings (human and non-human); and (4) efforts by the cultural bourgeoisie to create places of meaning. We gathered data through regular, predominantly passive observation of industrial sites over a period of about 10 years. We visited 40 such sites. I made repeated visits to 8 of these sites because they are located in the part of Bucharest where I live (Filaret - Parcul Carol - Tineretului - Timpuri Noi area). I often walked and drove near other post-industrial sites, sometimes stopping for a few minutes just to note what had changed, other times spending a few hours when unique events such as demolitions or urban mining activities were taking place.

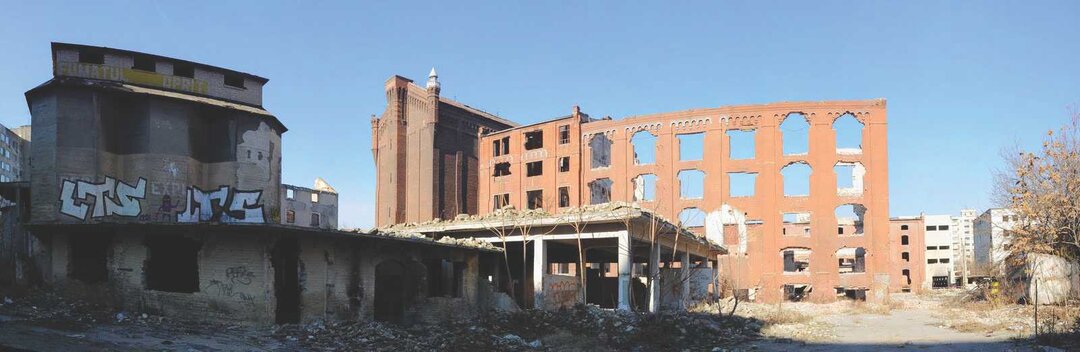

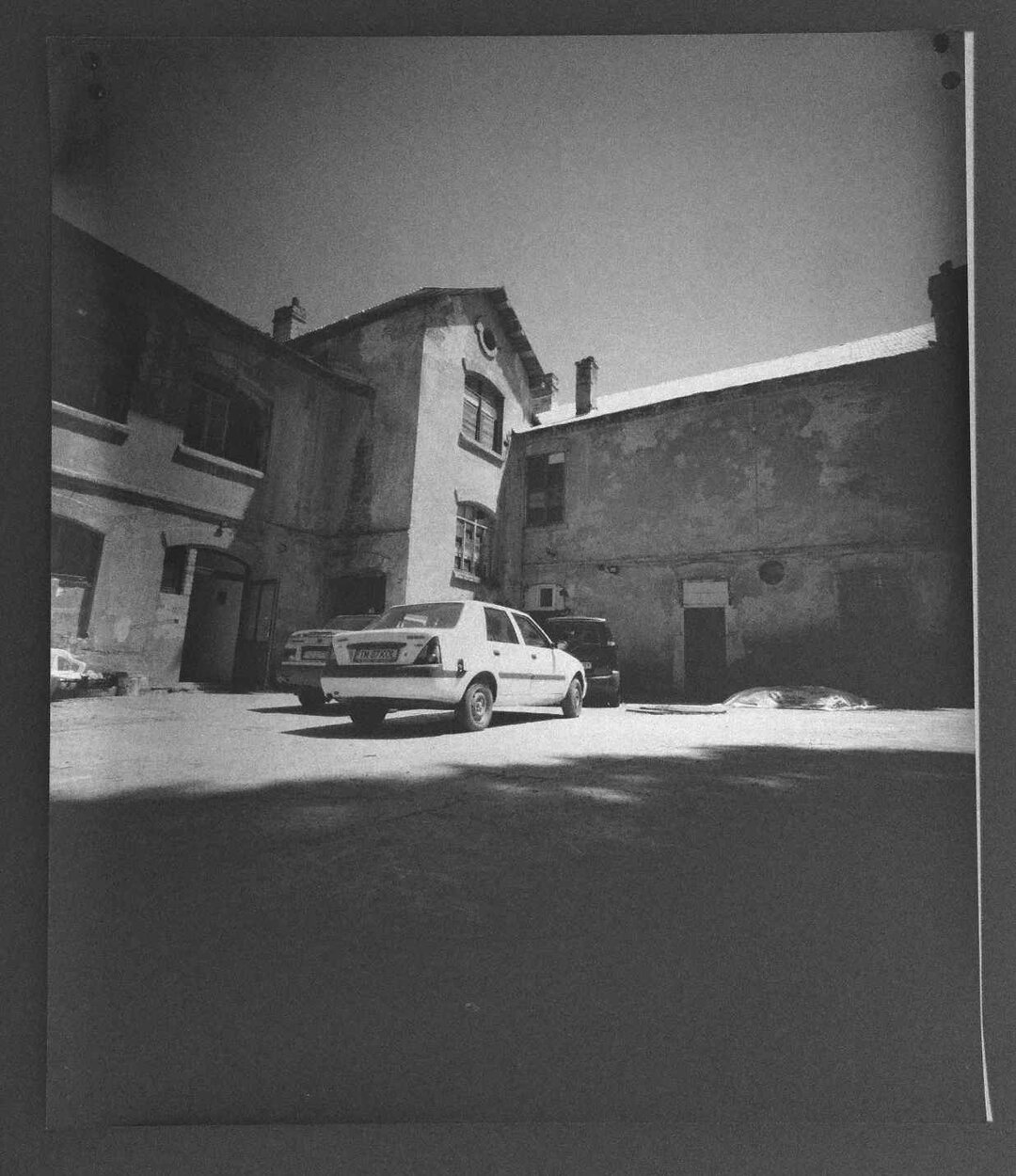

An emerging eclectic ecology: urban mining, playgrounds and shelters for the marginalized

With the cessation of production, many such sites are no longer protected, allowing mixed industrial materials to transform under the concerted action of people, plants and animals. A key set of actors playing a role in reshaping this new ecology are the disadvantaged families and individuals who collect scrap metal and bricks. Their extractive efforts equate to what Wallsten et al. (2013: 85) call urban mining, i.e. spatially concentrated, mineral-rich target areas (infrastructure mines) concentrated in the same space within city limits (see also Wallsten, 2015). The dynamics of such extractive clusters are quite varied. Sometimes the owners of former industrial sites dismantle mobile and easily removable metal elements from these spaces and sell them to ferrous scrap centers. Factories are selling old large appliances, disused assets and structures made of metal from former industrial sites. When this downward circulation of material values ends, most factories are morally abandoned by their owners, resulting in the loss of security, either intentionally or due to lack of resources to protect the perimeter. Once this happens, outsiders are able to enter the compound. Some are former workers, but most often they are disadvantaged groups who live in the vicinity of the factories or are constantly looking for scrap metal around the city (Fig. 1 and 2).

I have witnessed such episodes of urban mining. In some cases, the groups collecting ferrous materials are made up of couples of underprivileged young people who carry the scrap iron with their arms or with the help of carts. Once, I found an adult accompanied by three children demolishing the entrance of a building together. In other cases, the groups are considerable in size, consisting of 10 to 100 people. The largest group I encountered was at the New Times Factory, an old enterprise built in the second half of the 19th century. Located relatively close to the city center, it was demolished after the company moved its headquarters about 40 kilometers from Bucharest. The rubble from the demolished buildings was then broken into small pieces and piled into huge heaps by the demolition company. A few days later, a large group of poor families, including children, broke into the compound. For three winter days, from morning to night, they tore through the recycled concrete of the former factory in search of iron debris. They found cast iron pipes, cables and metal strips used to make reinforced concrete. They transported the pieces to a collection center 150 yards away, where the scrap was weighed and paid for in cash. Since it was a cold day on the threshold of winter, on the way back from the collection center they stopped several times at a convenience store to buy coffee and snacks before returning to the site. We counted, on average, four or five trips made by each group.

Other marginal resources are also extracted, such as bricks or wood for heating. The moment of destruction is followed by a new ordering of the 'deteritorialized' matter. This cycle of 'deteritorialization', appropriation and relocation of marginal resources is framed by important actors in the context of a 'negative reciprocity'..., which identifies the state as the primary culprit (Mateescu, 2004: 85). Ignoring property rules - perceived by the poor as an endless series of conspiracies against them - this type of families include the ownership of non-functioning factories in the realm of neighborhood property rights. During a foray into one such factory I had been monitoring for some time, I discovered a group of four children with their father tearing iron decorations off one of the administration buildings and carrying them to their nearby yard. On successive visits to another factory, I witnessed the gradual disappearance of the brick walls as neat piles of bricks were being erected in front of neighboring houses, which would later be put into circulation. The process of extracting and demolishing these spaces generates acres of maidan.

The emerging landscape is often a fascinating playground for children. For many children in such areas of Bucharest, the [industrial] slums are synonymous with a space of freedom, a childhood paradise, an urban materialization of plains, mountains or hills, all right in the backyard, in the forests populated by the oversized animals and frightening monsters we have been fighting for many years (Tudora, 2007: 1).

Well-known writer Mircea Cărtărescu said that some of his fondest memories are linked to the bread factory behind his block. This unplanned use is exacerbated by the fact that most post-industrial sites are located in neighbourhoods marked by a lack of parks and other open spaces, sub-average environmental quality and generally inhabited by communities affected by the very processes of industrialization and deindustrialization that were at the root of the creation of the sites in question.

This is rather the case of Bucharest, since the capital has the highest population density in Europe, with approximately 8,099 inhabitants perkm2, compared, for example, with 3,800 inhabitants in Berlin or 1,089 - in Dublin (Chelcea and Iancu, 2015: 64).

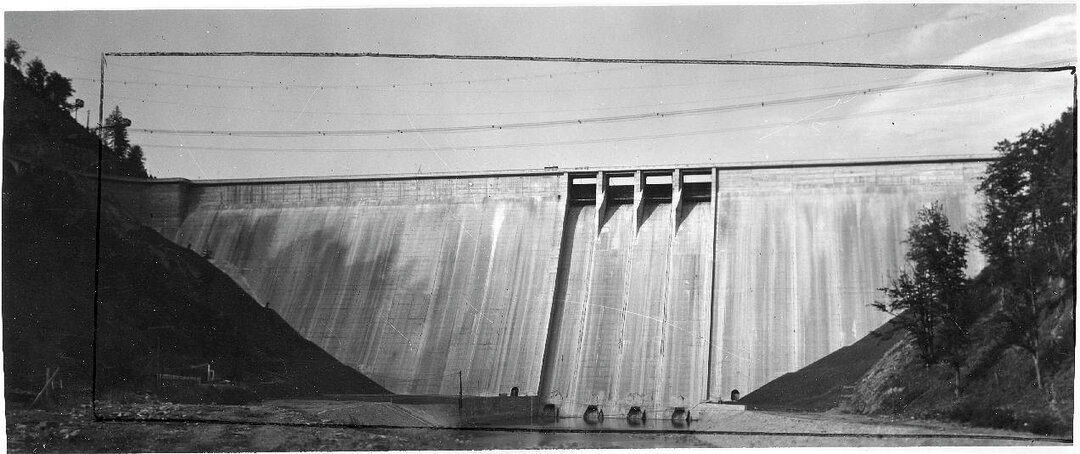

As previous efforts to separate nature from society (e.g. removal of ruderal plants, banishment of animals, prevention of degradation, etc.) cease, new actors emerge. Post-industrial spaces can also be seen as heterotopias, i.e. non-hegemonic places where sovereignty breaks down (Foucault, 1986/[1984]). There are other marginal urbanities that utilize such zones besides those practicing urban mining. Homeless people - a new discursive and locative pattern condition that emerged after the end of socialism (O'Neill, 2014) - sometimes end up spending the night in these places. Former industrial sites are, in a strange way, both private and public spaces, akin to the space surrounding the strip of land on which the Berlin Wall once stood. In such spaces, nature itself exerts an architectural function, modifying the existing one and thus transforming the appearance of the place and, implicitly, its function (Culescu, 2007: 2). As Joern Langhorst (2015: 2) points out, emergent ecologies can be considered the most authentic elements of urban nature because they are the physical expressions of processes that are not controlled by human maintenance systems and often manifest themselves in the earliest stages of vegetation cycles.

They stand in stark contrast to the expensive and fetishized nature promoted by the municipality's landscaping office (Public Domain Administration), represented by carefully manicured lawns, exotic plants (in relation to the Romanian climate) and the extravagant flower pots present in abundance on most of the city's avenues (Pondichie, 2012: 65-71).

As in other cities, once buried under the rich vegetation, these areas acquire a positive ecological value for Bucharest, generating new sites to be colonized by plants and animals (Box, 1999; Lachmund, 2013). In such post-industrial sites, as vegetation is fully controlled by nature and free from human intervention, it has a clear contribution to the self-regulation of the local microclimate, soil regeneration and temperature control (Culescu, 2007: 7). Culescu makes clear that the distinction between weeds and green turf is an arbitrary one, in the sense of a cultural distinction not based on intrinsic ecological value. These industrial lawns in Bucharest attract ruderal flora, bringing together species with a high degree of adaptation to the urban environment: pollution, overwork, poor soil, specific climatic conditions (Culescu, 2007: 3). Alongside industrial pests, plants spread to other marginal urban spaces such as roads, dusty paths or cracks in building walls (Figure 3). Non-human marginal creatures, stray dogs, owls, rats and even pheasants also find shelter in these places. Sometimes the animals are even welcome. Security guards rely on stray dogs to guard former industrial sites. During the day, the dogs sleep near the guards' booths; at night they roam free, alerting the guards to suspicious sounds or activity. People in neighboring neighborhoods are generally unhappy with the combination of rubble from factory demolitions and wild nature. They see the industrial ruins and the presence of ruderal flora and fauna - i.e. the ability to separate nature from society - as a double failure: the inability of the post-socialist transition to save the socialist-era industry and the inability of the market to generate a new use for such land.

The amalgam of the degradation caused by scrap-iron mining, uncontrolled plant growth and free access creates an ambiguous and amorphous landscape. A representative example of this is another factory in a central area that I regularly observed. Called "Frigul", it was built in the early 1920s and was located in the Filaret area, one of the first industrial agglomerations in Bucharest, which appeared near the first railway station built in 1869. "Frigul" produced and delivered ice and refrigeration plants for various businesses until the early 1990s. Until it was demolished, its premises consisted of a large building, most probably erected in the early 1950s, to which several smaller technical buildings were added.

At the beginning of the 1990s, due to the influx of cheap refrigerators, the factory ceased its activity. It functioned as a storage space for a while, after which it remained idle until 2005, and in 2006 it entered a demolition process that lasted almost a year. During that year, the freedom enjoyed by the remaining workers during the demolition created a carnivalesque landscape (Figure 4). Although I do not know who created this combination of female silhouette and factory equipment, this artifact is eloquent of the freedom of expression characteristic of this type of space.

After it was demolished, the land remained unused, becoming the refuge of a group of six to seven very well-behaved stray dogs (Figure 5). Fed by various people from the street and the neighborhood (including myself), they managed to survive in the area until the city hall killed them, without reason, in 2013. The area was fenced off with a metal fence, with the intention of building a gated community complex in the area, but no construction work has been initiated so far. Instead, the land has become overgrown. Since there is no significant activity, the new plants continue to grow unchecked beyond the fence.

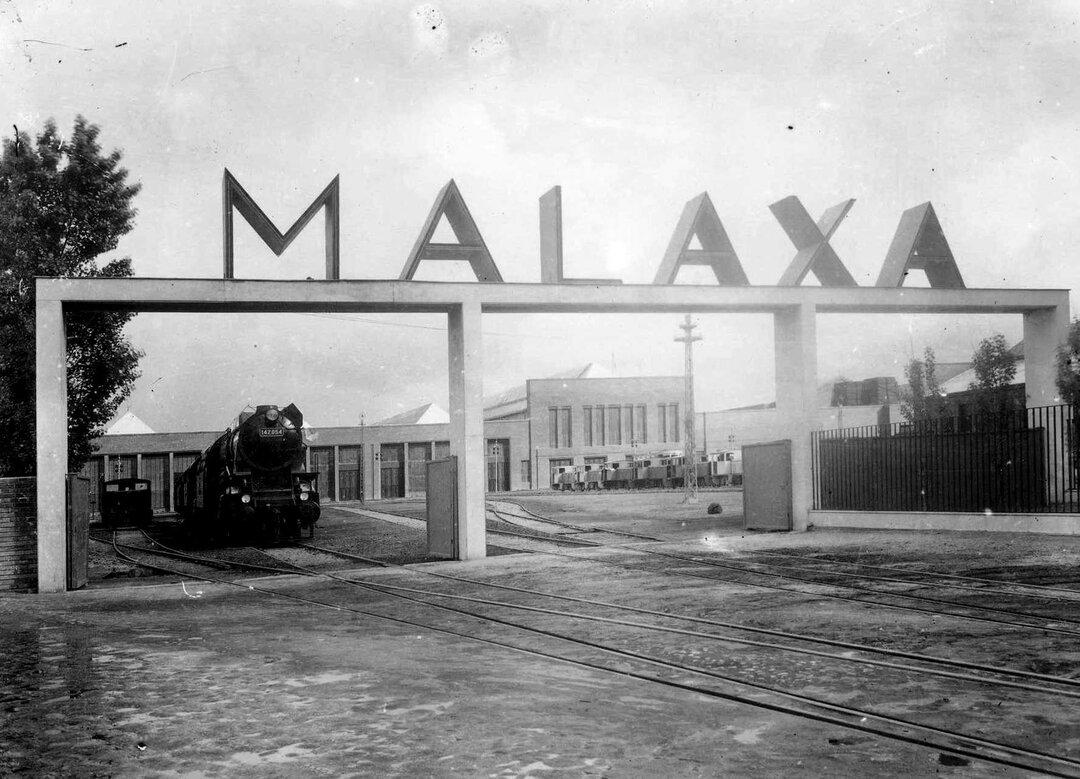

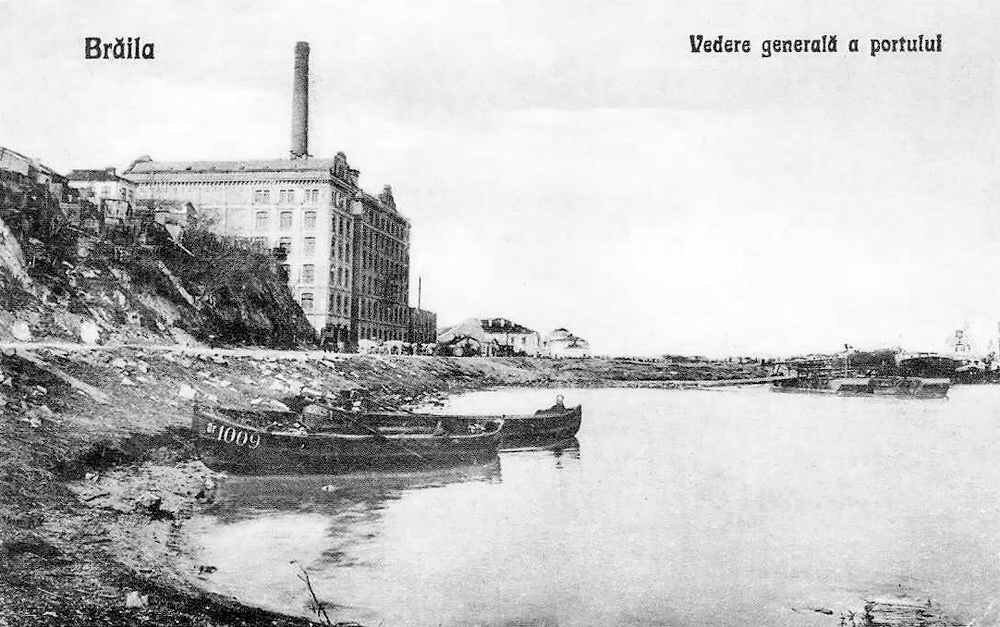

The Cold Factory is not an isolated case. Factories are closing and being demolished so that the land can be used for new construction. Between the time of demolition and the completion of the new building - a period that can take years - the owners usually keep the original fences to make it easier for security staff to work. This is also the case of a factory that has been producing rapeseed oil since 1899 (originally called Phoenix), bought by the large multinational company Bunge in the early 2000s, along with two other companies - major producers in Oradea and Iași. All three were closed in 2007, following the company's decision to relocate its regional investments to Latvia, Turkey, Ukraine and Poland1. During that year, the factory was demolished, apart from the large fence surrounding it, the main gate and the administration building. In general, these are retained as protective measures against homeless families who might take over such urban land, reinforcing Langhorst's (2015: 9) observation that the replacement of those guilty of ecological crimes corresponds to the exclusion and displacement of those guilty of social crimes. With the completion of real estate projects, the original fences are also demolished.

The struggle for meaning: from rubble and open meanings to ambiguous representations

As Gordillo notes, for the people who use these sites, the post-industrial landscape represents anything but the past. It is not some rubble from a distant past (Gordillo 2014: 19), but elements that are part of the economic and social configurations of the present. There is a category of people whose engagement with post-industrial sites is predominantly in the realms of urban exploration, art, heritage and, more generally, the production of meaning.

The rapid decay and symbolic ambiguity of post-industrial maidans frequently stimulate the curiosity of some of Bucharest's inhabitants, usually those active in artistic production, heritage conservation, antiquarians or collectors, plus conspiracy theorists looking for evidence of histories of power. These are the ones who strive to turn rubble into ruins, in the sense that they frame industrial materials in past eras, presenting them as objects separate from the present (idem: 8), reinforcing Langhorst's (2015: 2) point about the clear association between such post-industrial sites and their aesthetic and representational function.

In his classic essay on death, Robert Hertz argued that one's death is a complete process only when the decomposition of the corpse is complete. It is only when the deceased ceases to belong to this world and begins to enter another dimension that the end occurs (Hertz, 1960 [1907]: 47). An analogy can be suggested with the situation of the factories in Bucharest, which disappear without any of their component parts being saved or relocated to museums or archives, thus preventing any possible architectural destruction or closure. As such buildings are emptied of their significance - losing important elements such as machinery, archives, labor protection signs or other content-bearing inscriptions without even being photographed - their decay becomes a spur for creativity and imagination.

The speed and anonymity of the disappearance of these industrial spaces and their open nature lends an immoral character to their demolition. The art critic Michael Roth observes that disappearance, the danger of loss, is the secret of the attraction of ruins - and of their structural ambiguity (1997: 2). Such loss is particularly painful in the case of factories built in the early industrialization period of the 19th century. According to a specialist in industrial heritage, after World War II, the communist regime confiscated a number of machines, without seriously damaging them, out of a desire to use them with minimal replacement costs. In Romania [since the 1990s], exceptional technical equipment dating back to the 19th century can still be found in working order. Unfortunately, efforts to save this valuable heritage are practically non-existent (Iamandescu, 2005: 7).

These interpretative contexts reposition the rubble, granting it the status proper to ruins, i.e. objects of transcendental significance (Gordillo, 2014: 10).

Even the few factories that fall into the heritage category - thus being safe from demolition - cannot enjoy the status of objects worthy of preservation. Current legislation protects the facades of heritage buildings from the danger of demolition. Some facades are integrated, more or less harmoniously, into the fabric created by the new buildings erected after demolition; this is the case of the Stock Exchange or the Cartea Românească Printing House. However, there are also cases where the façade is completely separate from the rest of the newly built buildings, and is thus classified as a remnant structure in relation to the new urban constructions. Owners of sites containing heritage buildings usually wait - in the hope that they will eventually collapse by themselves. The New Times Factory - mentioned above - was forced to abandon the demolition of three buildings when other buildings on the site were demolished. Two years after the episode described above, the three heritage buildings disappeared and the whole site is now overgrown with various constructions.

In his classic essay The Metropolis and the Mental Life (2005/1903), Georg Simmel argued that the mental and sensory over-stimulation of urban life, when confronted with the hectic pace of the street, gives rise to an attitude of indifference or withdrawal into private space. In contrast, the flâneur described by Walter Benjamin is a strolling stroller who seeks out the hidden treasures of the city to spontaneously recall forgotten experiences. Abandoned factories are a common destination for flâneurs. Some tend to go about their business at a leisurely pace that betrays a perspective in which post-industrial sites are viewed as picturesque artifacts (Langhorst, 2015: 3). The more adventurous are not inconvenienced by the sensory lack of comfort caused by dust, water, excretions or unpleasant odors. For urban explorers, the tension between the mystery of these abandoned spaces and the sense of fulfillment experienced as a result of entering such enclosures is an attraction in itself. These places are visited and then described on various blogs under the title terra incognita, standing in opposition to post-socialist consumerist modernity (Văetiș, 2011: 89-91).A Bucharest exhibition presented to its visitors, among other things, a heap of rubbish gathered from the perimeter of Assan's Mill, an industrial landmark of the city (Figure 6), as part of an apparent protest against the lack of awareness of industrial heritage. Similarly, in the same exhibition titled Rubbish, Scraps and Ruins2 , artist Mircea Nicolae also displayed the metal letters that made up the name of the factory awaiting demolition (Figure 7). This artistic practice stands in stark contrast to the organized, carefully structured and motivated experience of redeveloped and redesigned sites, such as The High Line in New York City (Langhorst, 2015: 5). The letters were recovered during a visit to the site area by the artist in the company of a friend. They function according to what we might call, extrapolating Moshenska's (2015: 80) analysis, curated rubble, i.e. mobile artifacts of deindustrialization that can be preserved in [their] passive, degraded state with careful conservation and stabilization. This aesthetic choice resonates with Gordillo's (2014: 9) observation that 'rubble' signals, through an exclusivist decision, the disintegration of recognizable forms.

Such urban explorations are part of the process of re-symbolizing (Ritzer, 2005) mobile and immobile industrial artifacts. Culescu clearly describes how the administrative abandonment of these spaces creates a double positioning of society towards them: on the one hand, they are affected by the decrease in value (thus becoming endless abandoned and neglected slums); on the other hand, they acquire the moral dimension of sacred or forbidden space (2007: 9).

Michael Roth, emphasizing the relationship between ambiguity and creativity, has observed that ambiguity becomes a fertile ground for metaphor, so that bodies, ideas and artworks can be categorized as ruins, akin to buildings (1997: 2, see also Maskit, 2007).

The discovery and display of such places constitute highly interesting acts of appropriation. As legal scholars have emphasized, communicating claims to ownership is a fundamental form of exercising property rights (Rose, 1994). In the absence of visible signs indicating property rights to non-functioning factories, many post-industrial spaces seem to belong to no one, while the rest of the city benefits from clear rules regarding access, inclusion and exclusion. Through the presence of curators from outside the physical perimeter of former industrial sites or through digital representations on blogs, such people create an auxiliary alternative urban geography. A few years ago, on the website of the Romanian community of urban and industrial explorers, one could read the following announcement: "We are trying to gather as much information as possible about interesting places, abandoned or not, that are worth visiting or photographing". The fact that post-industrial sites are worth visiting shows the symbolic reintegration of industrial sites into the local cultural landscape.

The discovery of industrial sites after the flâneur's cessation of activity suggests a particular temporal regime. In a study of Detroit, Cope (2004: 11) notes that, following massive depopulation, the cityscape looks as if time stood still in the 1960s and nature has taken over. Also, the factories now existing in Bucharest have remained as they were in the 1980s. What's more, some look as if they were somewhere in the late 19th century when they were built. Many have not changed their appearance, fueling a certain sense of the picturesque (Langhorst, 2015: 3-4). In this context, the exploration of these sites is not only geographic and spatial, but also temporal. Such flâneurs devour not only urban space but also different historical periods. There is something postmodern and fragmentary in re-symbolizing post-industrial sites through exploration. They offer glimpses of history, not initiatives in search of lost time and personal memories, since none of these people had any connection with the factories when they were in operation. Their sensibility echoes Charles Jencks' observation that in contemporary culture people can live in several worlds at once: if people can live in different eras and cultures, why limit themselves to the present time and the local plane? Eclecticism is the natural evolution of a culture that is in a position to choose (Jencks apud Harvey, 1989: 87).

Conclusions

The ethnographic fragments presented above raise important questions about the articulation of concepts of value, power, nature, time, materiality and representation in contemporary societies. Many former non-functional industrial sites cannot be considered abandoned. Marginalized urban inhabitants, both human and non-human, use them in different ways. Some practice urban mining, collecting scrap iron and building materials that can be sold or reused in other situations. Such sites function as non-hegemonic, heterotopic spaces. Children have discovered that such neighboring spaces can make excellent playgrounds. People with limited material means turn these places into shelters, forced by the lack of social programs to live there at night. Plants and animals are also driven to these places, because here they can take refuge from a city in which the municipal administration, residents and zealous representatives of the city council spend large sums of money to isolate urban society from nature. In addition, I sought to demonstrate that such sites are challenging in relation to conceptual discourse and representation. The emerging eclectic landscape is difficult to name and hard to define. This type of sites resists the main descriptive patterns as interpretive landmarks. We have used a range of digital, artistic and heritage practices as tools in our endeavor to investigate this ambiguity. Urban explorers and artists use these spaces as resources in their work. In doing so, they seek to transform post-industrial rubble into ruins, to appropriate and reposition it in terms of other interpretive frameworks3.

Bibliography

Liviu CHELCEA, Bucureștiul post-industrial [Post-industrial Bucharest], Iași, Polirom, 2008

Mitch COPE, "In Detroit Time", in Shrinking Cities - Complete Works 1, Aachen: Arch+ Verlag Gmbh, 2004

Mihai CULESCU, "Linia verde București-Vest. Lucrare pentru examenul de cunoștințe fundamentale și de specialitate urbanism, maidane [The Green Corridor Bucharest West. Exam paper for the course urbanism, wastelands]", Bucharest, University of Agronomic Sciences and Veterinary Medicine - Bucharest, Faculty of Horticulture - Landscape Design Section, MS, 2007

Tim EDENSOR, Industrial Ruins: Space, Aesthetics and Materiality, London, Berg, 2005

Michel FOUCAULT, "Of other spaces", Diacritics, nº6, 1986, p. 22-27

Matthew GANDY, "Marginalia: Aesthetics, Ecology, and Urban Wastelands", Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 103, nº6, 2013, p. 1.301-1.316

Gastón GORDILLO, Rubble: The Afterlife of Destruction, Durham, NC, Duke University Press, 2014

Talinn GRIGOR and Romina KATCHI, 'Debris of What-would-have-been: A Photo-Essay Concerning Deindustrialization in Hyper-Capitalist and Post-Socialist Cities', Journal of Urban History, no. 8, 2015

Joern LANGHORST, "Rebranding the Neoliberal City: Urban Nature as Spectacle, Medium, and Agency", Architecture, Media, Politics, Society, vol. 6, nº4, 2015, p. 1-15

Irina IAMANDESCU, Industrial Archaeology: International Benchmarks and Romanian Contributions [Industrial Archaeology: Ioan Sebastian JUCU JUCU, "Romanian Post-Socialist Industrial Restructuring at the Local Scale: Evidence of Simultaneous Processes of De-/Reindustrialization in the Lugoj Municipality of Romania", Journal of Balkan and Middle Eastern Studies, vol.17, nº 4, 2015, p. 408-426

Jens LACHMUND, The Invention of the Ruderal Area. Urban Ecology and the Struggle for Wasteland Protection in West-Berlin, Paper presented at the International Sociological Association, Research Committee 21, Berlin, August 29-31, 2013, available at http://www.rc21.org/conferences/berlin2013/RC21-Berlin-Papers-2/23-Lachmund.pdf

Nate MILLINGTON, 'Post-industrial imaginaries: Nature, Representation and Ruin in Detroit, Michigan', International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37, 1, 2013, pp. 279-296

Gabriel MOSHENSKA, 'Curated Ruins and the Endurance of Conflict Heritage', Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, 17, 1, 2015, pp. 77-90

Bruce O'NEILL, "Cast Aside: Boredom, Downward Mobility, and Homelessness in Post-communist Bucharest", Cultural Anthropology, 29, 1, 2015, p. 8-31

Claudia POPESCU, "Deindustrialization and Urban Shrinkage in Romania. What Lessons for the Spatial Policy", Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 42(E), 2014, pp. 181-202

Georg SIMMEL, "The Metropolis and the Mental Life", in Jan LIN and Christopher MELE (eds.), The Urban Sociology Reader, London, Routledge, 2005 [1903], pp. 23-31

Ioana TUDORA, "Wasteland as Alternative: Spontaneity versus Planification", Manuscript, 2007

Șerban VĂETIȘ, "The Material Culture of the Postsocialist City. A Success/Failure", Martor, 16, 2011, p. 81-94

Björn WALLSTEN, "Toward Social Material Flow Analysis: On the Usefulness of Boundary Objects in Urban Mining Research", Journal of Industrial Ecology, 2015, available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jiec.12361/epdf

International Practices and Romanian Contributions], Manuscript, 2005

NOTES

1. http://www.bunge.com/company-history, accessed November 1, 2013.

2. Mircea Nicolae - Trash, debris and ruins. 2012, available at:

http://mircea-nicolae.blogspot.ro/2012/04/gunoaie-resturi-si-ruine.html

3. A first version of the text was published in Open Monument: Research on Ephemeral Commemoration Architecture and Modernist Patrimony, edited by Marta Jecu, Berlin: Revolver, 2014. https://pa.revues.org/448#tocto1n1 https://pa.revues.org/448#tocto1n1