The Architecture of the Malaxa Factories

text: Nicolae LASCU

1. Horia Creangă's industrial architecture is a special field of his creation. Although his fame at the time was due, for the most part, to the housing or public facilities that he built, his work in the field of industrial construction contributed decisively to the shaping of his personality.

The apprenticeship he completed in 1925, after graduating from the École des Beaux Arts, at the excellent Northern Railway Company in France, probably opened his interest in a field that was still too unattractive for Romanian architects. In fact, industrial architecture gained its place in the sphere of architectural creation with the achievements of some of the most important promoters of modern architecture, from Peter Behrens to Walter Gropius, Alvar Aalto, Erich Mendelsohn, etc. It can be said that for Creangă, industrial architecture was a constant throughout his entire activity. The approximately ten years of collaboration with the great industrialist Nicolae Malaxa1 continued towards the end of his life with the design of the three milk industrialization factories in Alba Iulia, Simeria and Burdujeni, minor works of course, architectural variations of a small-scale program. Horia Creangă's collaboration with Malaxa remains significant. He will be asked to draw up the projects for the most important buildings inside the industrial enclosure; he will also be entrusted with the design of the well-known Burileanu-Malaxa building on bd. Magheru. There were, however, works of different value and importance, which were realized by several other architects and conductors-architects. Richard Bordenache, for example, at the beginning of his career, would have the opportunity to design and build the extension of N. Malaxa's house on Modrogan Alley2 and to draw up the project for the factories at Tohanul Vechi3. Another architect, Dan Cotaru, designed the "Malaxa area" in the immediate vicinity of the Romanian pavilion at the Milan International Fair in 19404, when the products of the Romanian factories enjoyed great success.

Horia Creangă's relations with N. Malaxa were, therefore, among the most privileged. Although it is not possible to establish precisely how they began, it is only known that he was initially assisted by his brother.5 But in a note published in 1937 in the "Gazeta Municipală", a long-lasting collaboration is confirmed: "Arhitect al soc. Malaxa was always Mr. arh. Horia Creangă"6 (s.n.).

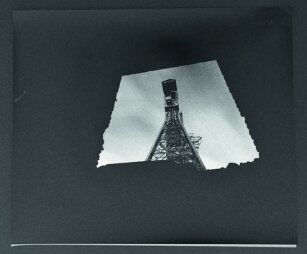

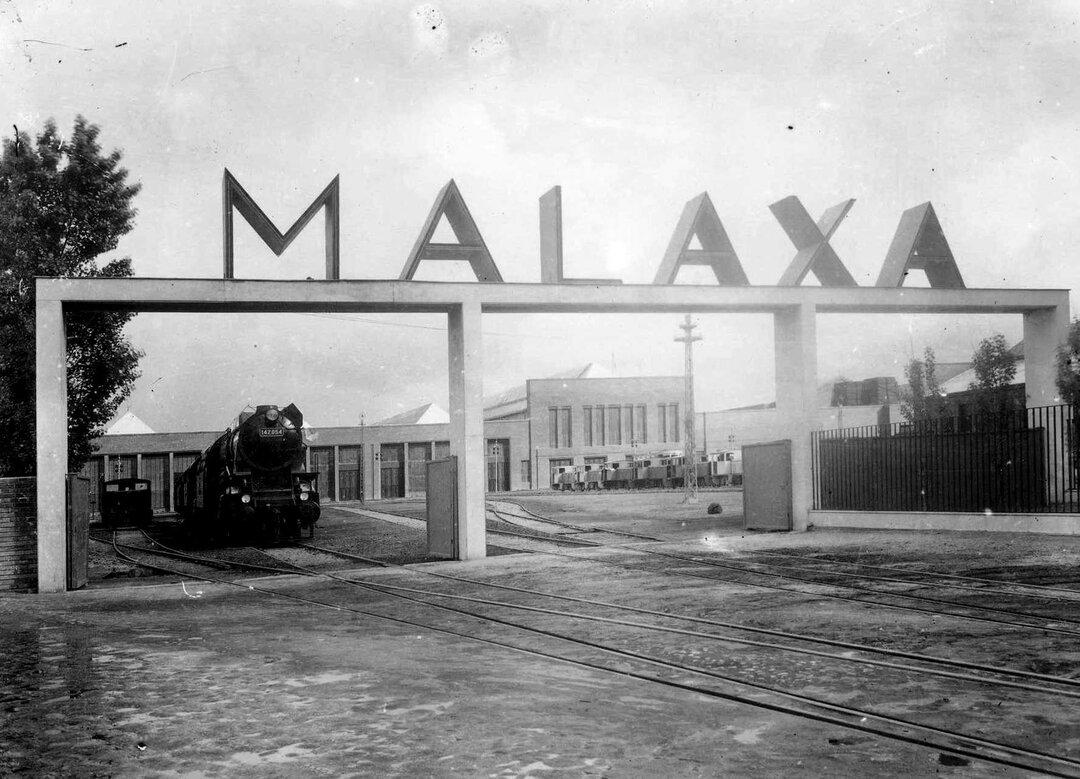

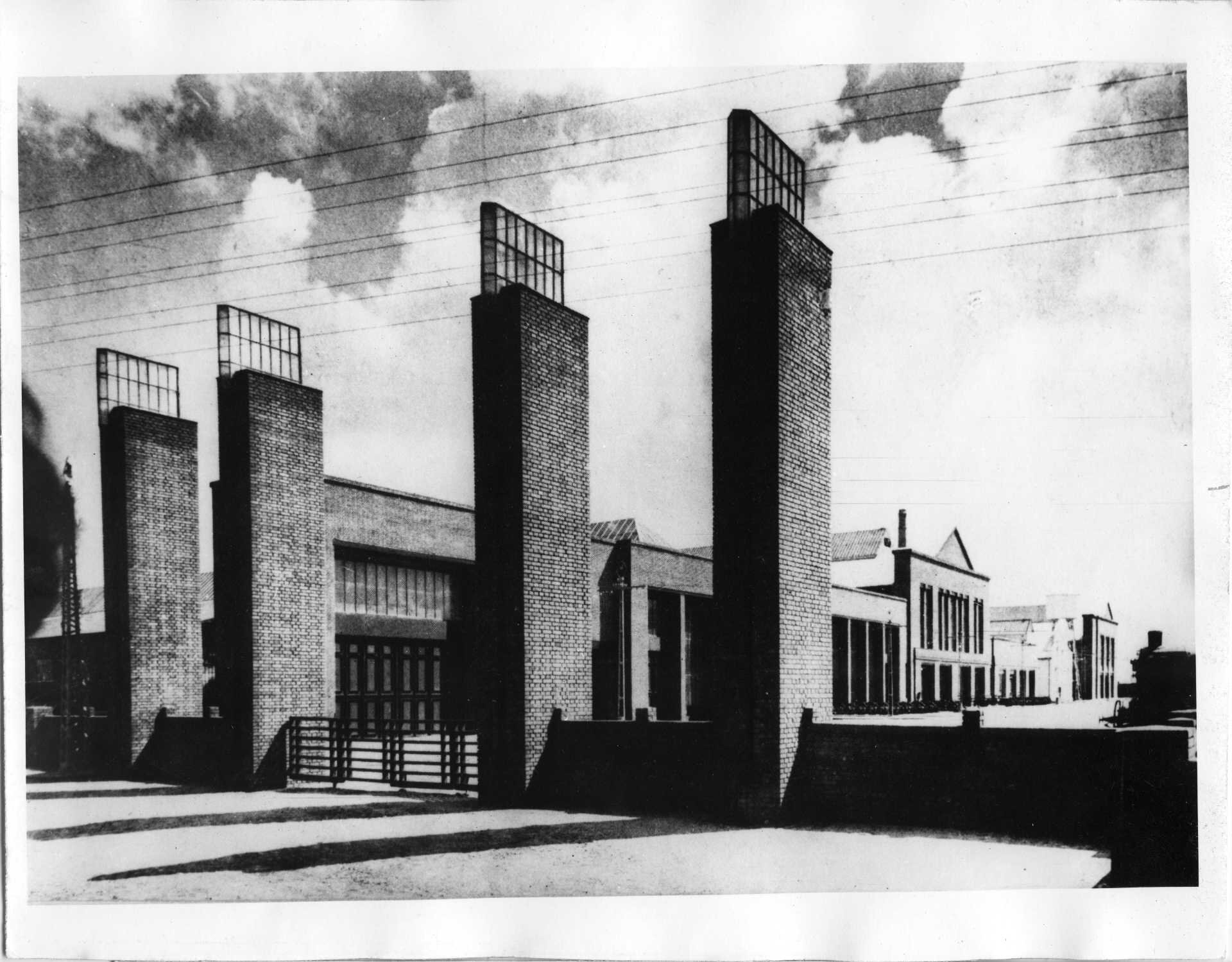

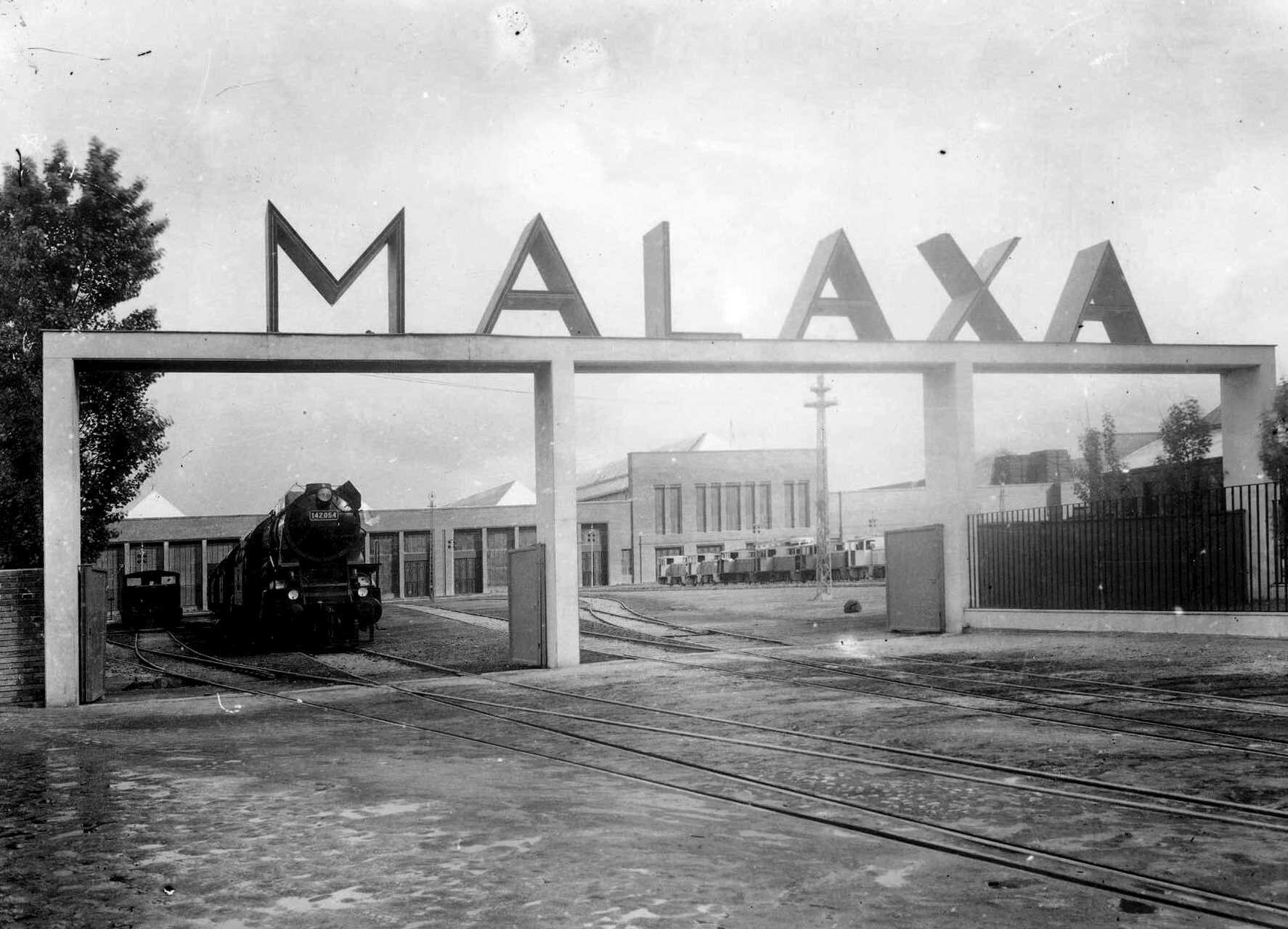

Among his first interventions - in the years 1930-1931 - was the main entrance to the enclosure, treated as a vigorous signal, made of four massive pillars of apparent brick, finished at the top with small vertical, glazed volumes, lit at night, which seem to grow organically from the discreet continuous vertical slit in the middle of the small side of each pillar. The entrance was immediately appreciated as one of the significant achievements of Romanian modern architecture, as did, for example, G. M. Cantacuzino7. The set of four pillars, together with one of the types of locomotives manufactured at Malaxa, was the emblem of the plant in the 1940 leaflet-claim. In the year of its realization, the entrance, monumental in itself, was rather an exceptional constructional achievement of that period of the "Malaxa" Works, anticipating Creangă's later creation.

2. Our great architect was one of the most active witnesses of the astonishing leap of these factories. Indeed, in 1921, the engineer Nicolae Malaxa bought a plot of land near the CFR Titan station, on which, on January 1, 1928, the first pillar of the first hall of the future Locomotive Factory was erected, and on December 28 of the same year the first locomotive was delivered.

2. Our great architect was one of the most active witnesses of the astonishing leap of these factories. Indeed, in 1921, the engineer Nicolae Malaxa bought a plot of land near the CFR Titan station, on which, on January 1, 1928, the first pillar of the first hall of the future Locomotive Factory was erected, and on December 28 of the same year the first locomotive was delivered.

By the end of the following decade, the "MALAXA" S.A.R. Works - through its three component companies: the Locomotive Factory, the Tube and Steel Works and the Tohanul Vechi Factory - had become one of the pillars of Romanian industry, "a company of international scope"8. In 1933, only a few years after the first locomotive was manufactured, "Malaxa" started the production of railcars - considered to be the forerunners of the first technical revolution in rail transportation - which, over 7 successive "generations", would reach the highest world level of the time. The expansion of the field of activity will be reflected after 1936 when, with the establishment and construction of the Pipe Factory (Republic Enterprise), the "Malaxa" Plants - and through them Romania - will have the most modern factory of rolled tubes in Europe. A few years later, it would become one of the Romanian army's main ammunition suppliers. This giant of the Romanian industry, modern not only in terms of the products manufactured, but also, perhaps above all, by the dynamic composition of the entire manufacturing cycle, by the efficiency and elasticity of its organization, had become "an integrated plant, not dependent on any foreign or domestic supplier"9. It was thus possible to state, with undisguised pride, in an offer to MAN to manufacture aircraft engines, that "the problem of manufacturing any type of engine at the "Malaxa" company, apart from the fact that it is no longer an unsolvable technical problem, but by the very technical and economic independence of the "Malaxa" plants, it can be solved much more quickly than in any other plant in the country"10. The "Malaxa" industrial "phenomenon" will trigger the development of some of the most remarkable programs of industrial architecture of the entire interwar period, in the center of which, directly or indirectly, Horia Creangă will be at the center. The needs of the production development imposed, first of all, at an almost continuous pace, the construction of new warehouses and the extension of the existing ones. The halls were, however, an important part of the financial circuit set up by Malaxa: advances on works were invested in buildings and machinery which, in turn, were used to guarantee loans11. Like production itself, which was rigorously dependent on it, the development of productive premises was carried out according to strict annual plans12. The gradual expansion of factories on new areas of land led to the emergence of problems of spatial organization and volumetric relationships, the solution to which would take on consistent urban and architectural determinations. It can be said that all this development was based on modern concepts - at least for Romania - in terms of the organization and arrangement of the work environment, starting with the unquestionable prestige of the general image of the premises and ending with the attention paid to the workplace and the changing rooms. It was not by chance that Horia Oprescu said of Creangă's interventions that: "For the first time the worker was treated with something other than phrases"13. On the other hand, the very development of the factories required the expansion - or the creation - of office buildings for the administration, for the company's own research laboratories14 (which would later become a real institute), centralized warehouses and warehouses (equipped with the most modern vertical storage systems for goods), power and heating plants that ensured the independence of the factories, etc.

After 1936, Malaxa's interest shifted with a certain insistence towards equipment with a strong social character. In the 1940 budget, these were more clearly outlined in the so-called "Malaxa SAR Home"15, a set of measures, unfortunately not carried out because of the outbreak of the war, which included, for example, the purchase of land for the "housing park for civil servants", the creation of a canteen for all categories of employees16, a home for apprentices, trade schools - one for the lower and one for the upper classes, etc. Richard Bordenache's project of August 1, 1936 for the new Titan passenger station, which Malaxa offered to build at its own expense to provide its employees with better travel conditions, also remained unfinished17. In spite of Malaxa's concerns and, above all, his intentions, we do not think that he could be classed among those industrialists for whom the transformation of the working environment derived from a more general community conception or even theory, with more pronounced social overtones, as demonstrated by Krupp in the second half of the last century or, after the Second World War, by Adriano Olivetti in the Italian city of Ivrea. This evident openness of interest in the quality of the industrial workplace - a direction which, between the two world wars, had innumerable architectural successes in many European countries - can be understood rather through the prism of the desire to achieve ever greater efficiency and effectiveness, which, however, were not possible without substantial efforts directed towards improving the quality - physical and therefore also psychological - of the spatial environment offered. Nicolae Malaxa was probably the only Romanian industrialist who, between the two world wars, paid so much attention to these aspects of modern industry.

After 1936, Malaxa's interest shifted with a certain insistence towards equipment with a strong social character. In the 1940 budget, these were more clearly outlined in the so-called "Malaxa SAR Home"15, a set of measures, unfortunately not carried out because of the outbreak of the war, which included, for example, the purchase of land for the "housing park for civil servants", the creation of a canteen for all categories of employees16, a home for apprentices, trade schools - one for the lower and one for the upper classes, etc. Richard Bordenache's project of August 1, 1936 for the new Titan passenger station, which Malaxa offered to build at its own expense to provide its employees with better travel conditions, also remained unfinished17. In spite of Malaxa's concerns and, above all, his intentions, we do not think that he could be classed among those industrialists for whom the transformation of the working environment derived from a more general community conception or even theory, with more pronounced social overtones, as demonstrated by Krupp in the second half of the last century or, after the Second World War, by Adriano Olivetti in the Italian city of Ivrea. This evident openness of interest in the quality of the industrial workplace - a direction which, between the two world wars, had innumerable architectural successes in many European countries - can be understood rather through the prism of the desire to achieve ever greater efficiency and effectiveness, which, however, were not possible without substantial efforts directed towards improving the quality - physical and therefore also psychological - of the spatial environment offered. Nicolae Malaxa was probably the only Romanian industrialist who, between the two world wars, paid so much attention to these aspects of modern industry.

A "factory integration", in terms of production complexity, would naturally be matched by a similar complexity in terms of construction, which is, after all, an architectural and urban planning issue. In 1935, there was a construction office which, towards the end of the decade, would be transformed into a "building and new constructions department"18, which also included Nicolae Măndășescu, a devoted collaborator of Creangă in all his projects for Malaxa.

It was Horia Creangă who was to make the greatest contribution to the materialization of N. Malaxa's constructive intentions, consecrating an unmistakable image of Romanian industrial architecture between the two world wars.

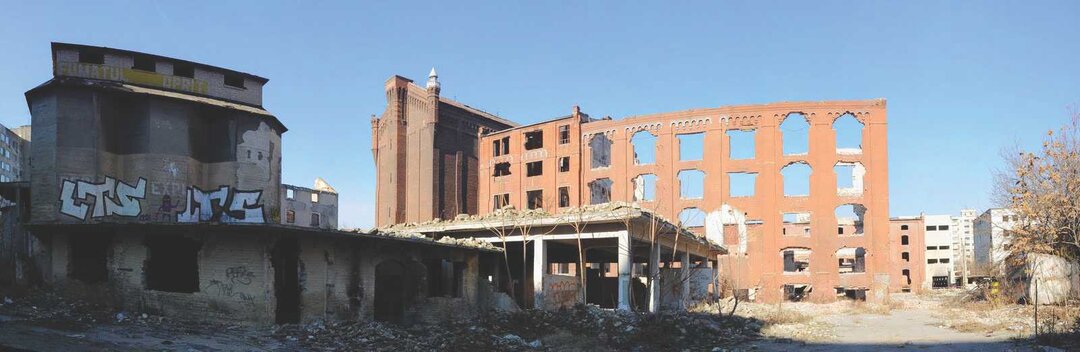

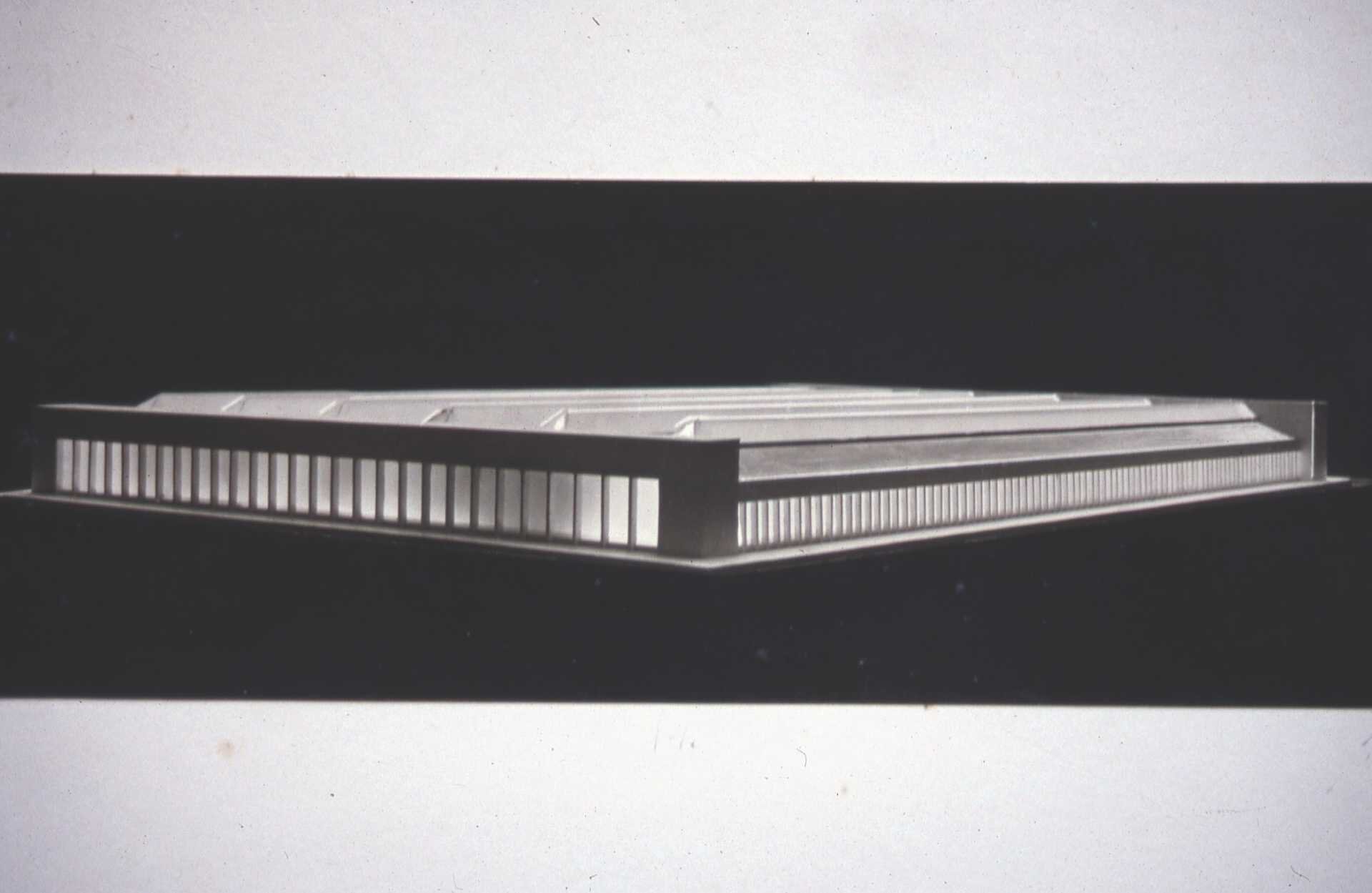

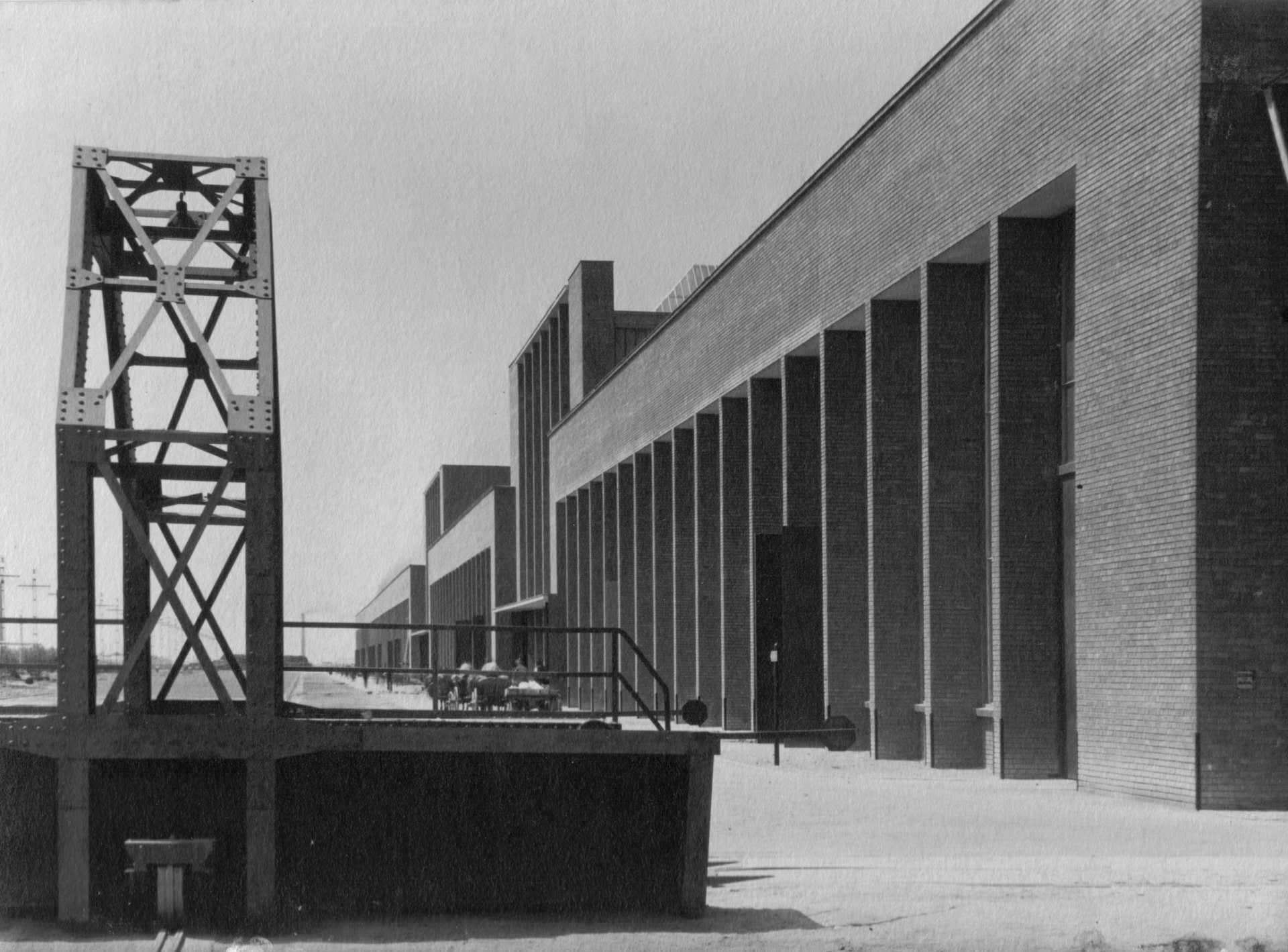

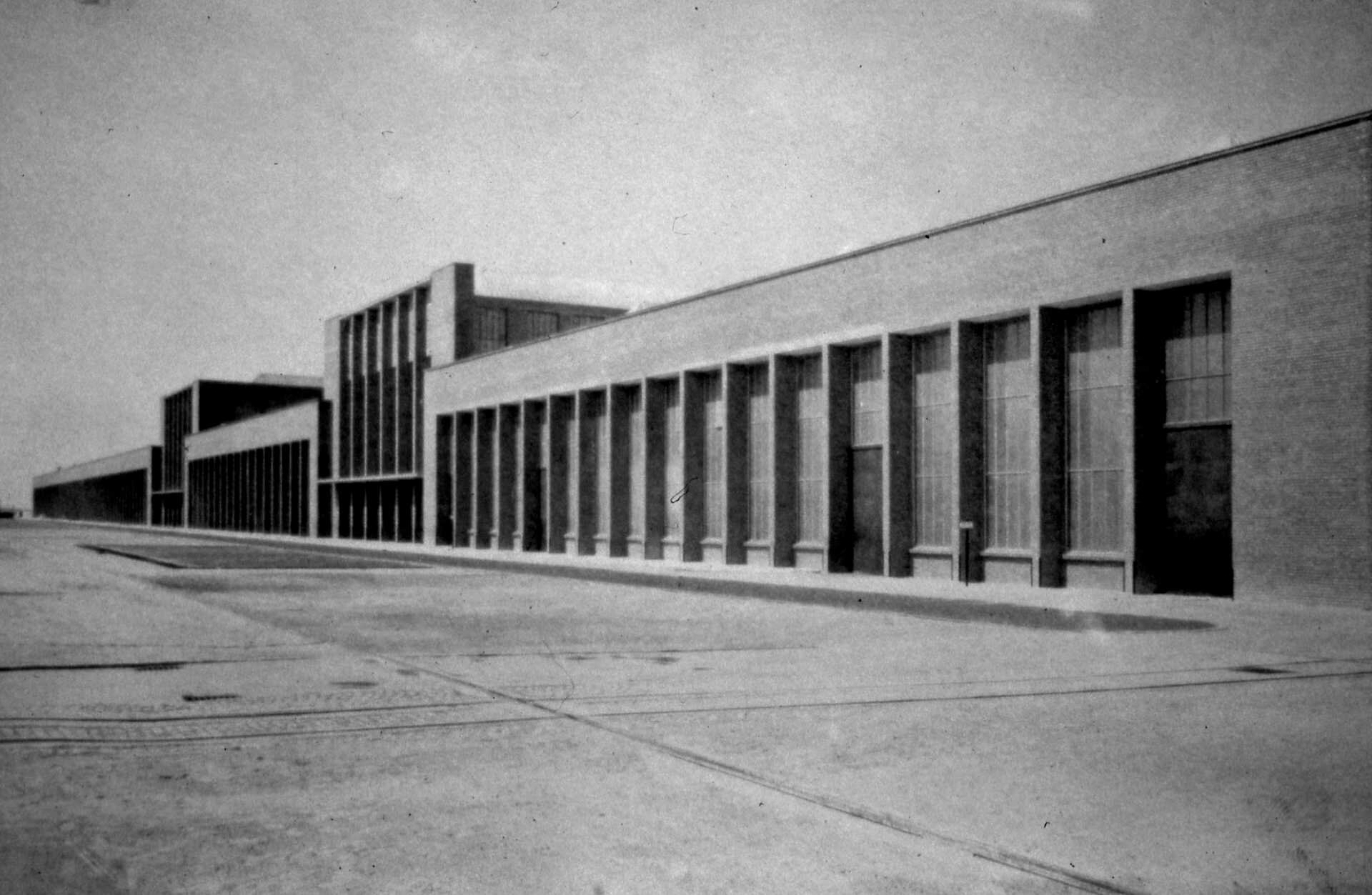

3. The period of maximum expansion and diversification of production began, in the middle of the 4th decade, with the realization of the Pipe Factory, built on a site adjacent to the old halls of the Locomotive Factory. Of impressive dimensions - 180/300 m - imposed by the technological conditions, the factory hall has a metal structure, built by UDR (Uzinele de ferro și Domeniile Reșița), where N. Malaxa was, in fact, one of the shareholders. Horia Creangă preferred the perimeter enclosure of the hall with brick masonry to a construction of possible total transparency, as suggested by the charming image of the metal structure, which would have, however, seriously inconvenienced the interior microclimate, thus creating a powerful image of a simple and clear volume which, on the north and south sides, ends in two taller bodies. The perfect unity of the volume is given by the uniform rhythm of the facades, with vigorous piers that delimit identical, remarkably proportioned recesses. The wall surfaces of the hall thus remain entirely glazed, allowing, together with the skylights, very good illumination of the hall. The way in which the walls are treated reduces the direct, uncomfortable light, the intensity of which is reduced by the strong shadows cast by these massive stacks. Where the technological process made it necessary, the glazed surface of the recess was replaced by large sliding or folding metal doors. The north side of the hall, with an orientation favorable to direct lighting, allows the appearance of a glazed wall of approx. 2,000 square meters19, mounted in a cantilever, in front of the façade surface. It is very likely that Horia Creangă's architectural achievement impressed, first and foremost, its beneficiaries. The building of the Pipe Factory certainly also brought about a certain change in the plans for the expansion of the factories. When, at the end of 1937, the construction possibilities for the new foundries and the steelworks were being analyzed, it was decided to build them in a single hall, even though these functions were usually located in separate buildings: a 180 x 60 m hall would "concentrate the iron and metal foundries, the steelworks, the pattern store, etc"20. The large dimensions of the hall were justified by the possibilities of extension and for architectural reasons, in order to maintain a 180 m front, like the front of the pipe factory"21 (s.n.), so that later, by installing other necessary machinery, "a building block like the pipe factory block"22 (s.Indeed, the building of this hall followed exactly the intentions so clearly stated: it is located a short distance from the Pipe Factory hall, on the same alignment, and the north-facing façade is enclosed by a glazed area of identical dimensions. The Pipe Factory Hall has thus become a model, but also a veritable, repeatable "module" of the industrial giant "Malaxa".

4. The construction of the halls belonging to the Locomotive Factory had a most interesting evolution, in several stages, which highlight the successive clarifications in the spatial and volumetric organization of the enclosure.

4. The construction of the halls belonging to the Locomotive Factory had a most interesting evolution, in several stages, which highlight the successive clarifications in the spatial and volumetric organization of the enclosure.

Horia Creangă's first interventions probably date back to 1930, when, together with his brother, he refurbished the two halls, realized in 1928 by the architect N. Petculescu23, and later designed new halls. Their sizing and the extension of the existing ones were initially closely linked to the technological requirements of the time, resulting in buildings of different sizes and heights.

The halls built from the second half of the 4th decade onwards were of identical length - 120 m24 - with a steel frame structure and metal skeleton skylights. This option, with obvious architectural implications, of which Creangă was certainly no stranger, was favored by the manufacturing process, which required the halls to be arranged in a row, with long sides and accesses at the ends. The elongated shape, as well as their stringing, suggested the architectural unification of the main facades. In this case too, Horia Creangă was present with his suggestions and then with his projects. The "uniformization of the fronts", which appeared as an intention in 193625, was to be gradually achieved in the following years, when the old halls were given a unifying facade, rhythmically decorated, as in the case of the Pipe Factory, with apparent brick piers. The two parallel building fronts, which are about. 50 m apart, will acquire a new and coherent architectural image. The extension of the two fronts, with the halls that appeared later, was achieved by respecting the same uniform cadence of the facades. The great length of the fronts - one of them is approx. 500 m - treated almost identically, far from suggesting monotony, help to establish a certain monumentality to the ensemble, as well as conferring an undeniable presence. The monumentality here is the result of identical relationships between the full and the empty, between the illuminated and the shaded surface, of the relationships between the concreteness of the finishing material and the transparency of the glazed surfaces, while the geometric relationships between the elements are firmly controlled by Creangă.

The tendency towards volumetric and formal order becomes increasingly evident towards the end of the 4th decade; some extensions to the halls will be made with the aim of defining perfectly regular volumes. The unification of the rear fronts completes the effort of constructive organization. The Malaxa factories will thus have all the productive spaces grouped together in several massive, regular, large-scale volumes; one of these, between the pipe factory and the administrative pavilion, is an impressive block measuring 120 x 500 m. The coherence of the whole ensemble of factories is also given by the use of a single finishing material - that is, facing brick. It is not, therefore, a question of cladding the plinths with a particular type of finish, but of constructing all the masonry surfaces entirely from a single material, expressed as such, in all sincerity. Horia Creangă, as in the case of the Obor Halls, chose this material for its resistance and aesthetic qualities. The shapes and volumes of the large factory buildings are emphasized by the material; they gain in the precision of their spatial delineation and the intersections of planes. The exceptional quality of the bricks and the particularly meticulous workmanship once again highlight the tenacity with which Creangă sought to use the best quality materials, a prerequisite for the durability of the buildings. All the more reason to bear in mind the observations made in 1934 by G. M. Cantacuzino, who noted the rarity of the use of apparent bricks: 'Bricks are (in Romania) always of poor quality. Apparent brick is not commonly found. When specifically ordered, its price more or less equals that of stone' (n.d.). In these circumstances, the material used contributes to making the whole ensemble more precious, raising it from the status of a mere utilitarian construction.

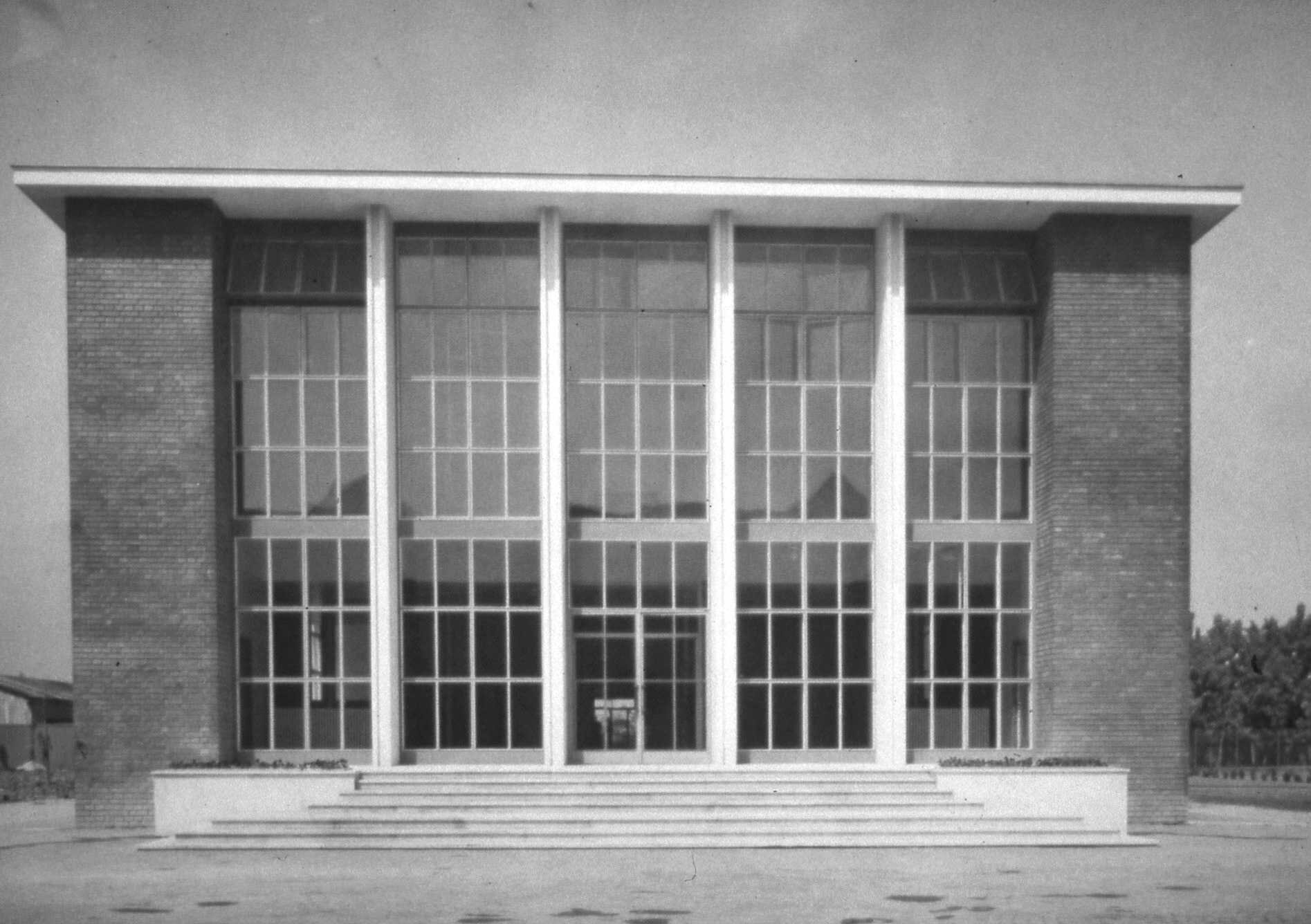

5. Horia Creangă also drew up the designs for the administrative pavilion (1936) and the factory laboratory (1937). These buildings are much smaller in size than the technological halls, and their functional solutions are simple and rational. They are both attempts to "articulate" the clearly defined language of the production halls with that of the architecture of its constructions in the urban environment. The laboratory building emphasizes the contrast between the massive brick plinths in the corners of the volume and the dominant glazed surface of the facades, rhythmed by the slender piers clad in white stone, while the administrative pavilion, using the same two finishing materials, vigorously marks the two levels with important functions, set on the ground floor, treated as a plinth, clad in white stone. In both the laboratory and the administrative pavilion, Creangă used, probably for the first time in the country, exterior wooden windows of the guillotine type.

The same architectural intentions can be seen, perhaps more clearly, in the unrealized 1939-1940 preliminary design of the management pavilion of the Malaxa Tube and Steel Works.

The administrative pavilion deserves special attention. The building has a part that is commonplace today - the double-tract office bar, in which the functions are strictly hierarchized by levels: the ground floor is intended for access to the pavilion and the enclosure, as well as for annexed spaces (warehouses, multiplication, etc.); the first floor - for the factory management (a large and luxurious office of N. Malaxa, two conference and negotiation rooms, offices for the senior staff), and the second floor - for the design and drawing workshops. The functional differentiations will find their counterpart in the varied spatial treatment of the interiors, from completely enclosed perimeter offices to the almost total visual continuity of the second floor. This remarkable transparency is achieved by glazed walls both between the offices and between the offices and the corridor, and by a uniform parapet height identical to that of the exterior windows. Separation of the interior spaces is achieved, wherever possible, by fixed storage furniture clad in walnut and oak veneer.

6. Both the realizations and the unfinished projects elaborated for the "Malaxa" Factory represent, as a whole, one of the most important expressions of Horia Creangă's creativity. The long collaboration allowed him to make repeated use of formal themes which, over time, led to the definition of his own architectural language. In some cases, we can see the "transfer" of compositional elements to "civil" architecture. This can include the rhythm of large facade deployments with particularly expressive pilasters (on some portions of the Cultural Palace in Chernivtsi or even the pavilions realized for the 1939 exhibitions), the zenithal illumination of some public spaces by means of metal skylights (the ticket office lobby at the ARO Palace on Calea Victoriei or the hotel lobby of the Cultural Palace in Chernivtsi), the use of exposed brick plywood (Halele Obor, under an identical motivation at "Malaxa", as well as the beige plywood used simultaneously at the ARO Hotel in Brasov and the Cultural Palace in Chernivtsi), etc.

On the other hand, this collaboration allowed him to express some essential aspects of his creative personality; the architectural gesture of great breath, the expressive force of large, sharp volumes, precisely cut out in space, the vocation for the elementary geometry of simple volumes, rather than for the particularization of different interior functions, find in "Malaxa" a most suitable place to express themselves. It should also be noted that the architecture of the 'Malaxa' complex of buildings has not undergone any major development or change over time, as is easily observed in the case of residential buildings - whether villas, blocks of flats or holiday homes - or public amenities. From his earliest works, the formal concept is expressed with great certainty and clarity. The consistent use of the same formal register, right up to his last works, without the slightest hesitation, attests to the fact that Horia Creangă had identified the most appropriate correspondence, from his point of view, between an industrial function and the formal character of architecture. The association of the two names - Horia Creangă and Nicolae Malaxa - has symbolic value for inter-war Romanian society: both personalities express the aspiration towards the rapid and full modernization of different fields of activity which, in this case, overlap. Horia Creangă gave the "Malaxa" factories - this giant of inter-war Romanian industry - an unmistakable, defining architectural image with which it identifies to a large extent. Creangă's architecture became one of the symbols of the factories.

More than his contemporaries N. Nenciulescu, G. M. Cantacuzino, Octav Doicescu, Richard Bordenache, L. Constantinescu or P. E. Miclescu, authors of important industrial buildings, Horia Creangă contributed to the removal of this type of construction from anonymity and banality. Through his realizations, the issues related to industrial buildings have won the right to architectural creation.

Notes

1. Radu Patrulius, Horia Creangă. Omul și opera, Bucharest, Ed. Tehnică, 1980, p. 56. The period is 1930-1940.

2. APMB - DT, file 61/1938, sector I Galben, file for building authorization.

3. Grigore Ionescu, Istoria arhitecturii în România, vol. II, București, Ed. Academiei, 1965, p. 478.

4. Ing. Henry Holban, Contribuții pentru o istorie a Uzinelor "Malaxa", chap. VI. Automotoarele "Malaxa", ms, p. 26-27. The manuscript is at the Integral Project Institute in preparation for publication. We are grateful to Mr. Eng. Al. Zigmond for permission to consult this valuable document. The most important parts of the manuscript have seen the light of print in three successive issues of the Historical Magazine; see note 8.

5. R. Patrulius, op. cit.

6. "Municipal Gazette", VI, 1937, no. 258, Jan. 24, p. 6.

7. G. M Cantacuzino, Tendances dans l'architecture roumaine, "L'Architecture d'aujourd'hui", 1934, nr. 5, p. 58-61. The photographs illustrating the article include the entrance to the "Malaxa" factory. Dated before 1934, the year of publication of the article by G. M. Cantacuzino, is based on the presence of the entrance, in the configuration of the well-known photograph, in the topographical plan of the "Malaxa" Locomotive Factory, erected in 1931; see APMB-DT, file 75/1932 PMB.

8. Ing. Henry Holban, "Uzinele "Malaxa"", "Magazin istoric", 1991, no. 5 (290), pp. 33-36; no. 6 (291), pp. 85-88 and no. 7 (292), pp. 38-41. The present reference is in no. 5, p. 34.

9. DGAS - FMB, fonds Malaxa SAR, file 36A938, f. 18.

10. Idem, f. 16.

11. H. Holban, Uzinele "Malaxa", op. cit, no. 5, p. 35

12. Memoriu asupra investițiunilor de fazer pentru endozestrarea și completarea uzinelor în vederea réalisation Programma de fabricație pe anul 1935, DGAS - FMB, Fond Malaxa SAR, file 24-28 1936, f. 3-10; Fabrica de locomotive și mașini. Investment Program in 1936, idem, file 306-46/1936, f. 3-10; Rolling Stock and Machinery Factory. Provisions. 1 III 1938-31 XII 1928, idem, file 553-112/1938, L 15-20.

13. Horia Oprescu, "The Architect Horia Creangă", Vremea, 1943, no. of August 29, p. 8

14. N. Malaxa decided to set up his own laboratory for the resistance of materials and chemical analysis on the advice of Gogu Constantinescu. The initial equipment of the laboratory met the needs of the enterprise for over 30 years (!); H. Hoblen, Contributions...,op. cit, p. 9.

15. DGAS - FMB, fonds Malaxa SAR, file 209-33/1934-40, f. 142.

16. Idem, file 129-10/1932-37, p 1.19. The plan, on ozalid, contains a 1/200 scale plan of the canteen and 3 facades; the plan is signed by cond. arh. Dem. Dumitrescu.

17. Idem, file 477-36/1938, f. 1-3.

18. Idem, file 209-33/1934, f. 120.

19. Gr. Ionescu, op. cit., p. 477.

20. Extension of the factories and construction of the steelworks, study dated December 2, 1937; see DGAS - FMB, Malaxa SAR, file 393-53/1937, f. 29.

21. Idem f. 34.

22. Idem.

23. R. Patrulius, op. cit., p. 56.

24. Gr. Ionescu, op. cit.

25. Locomotive and Machine Factory Investment Program in 1936, op. cit., f. 7.