The Abandoned Mills of Brăila, Identity Benchmarks or Ghosts of the Danubian Industrial Heritage?

text: Maria STOICA

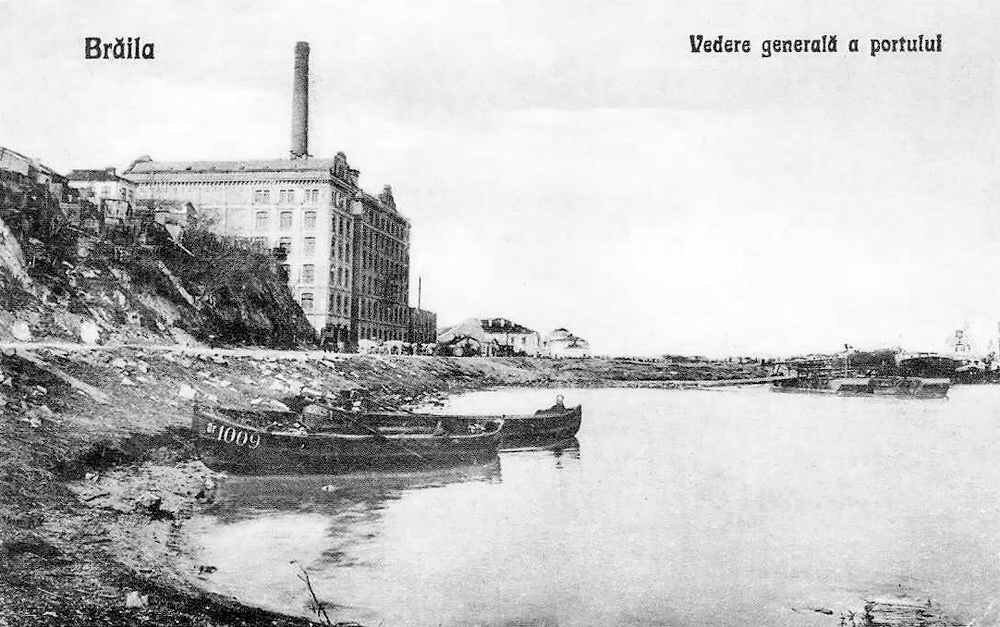

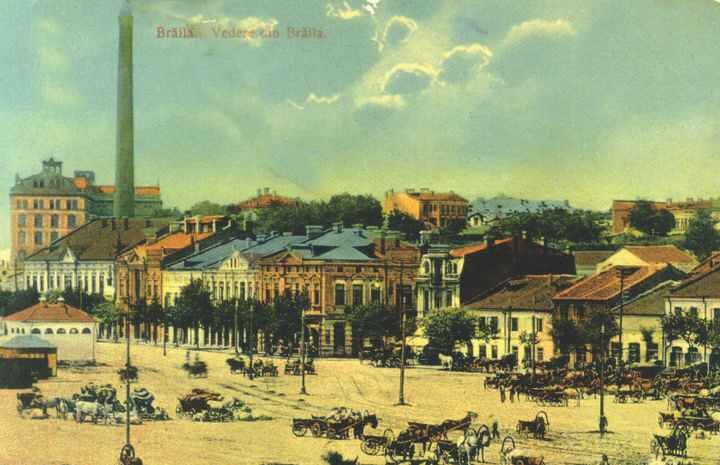

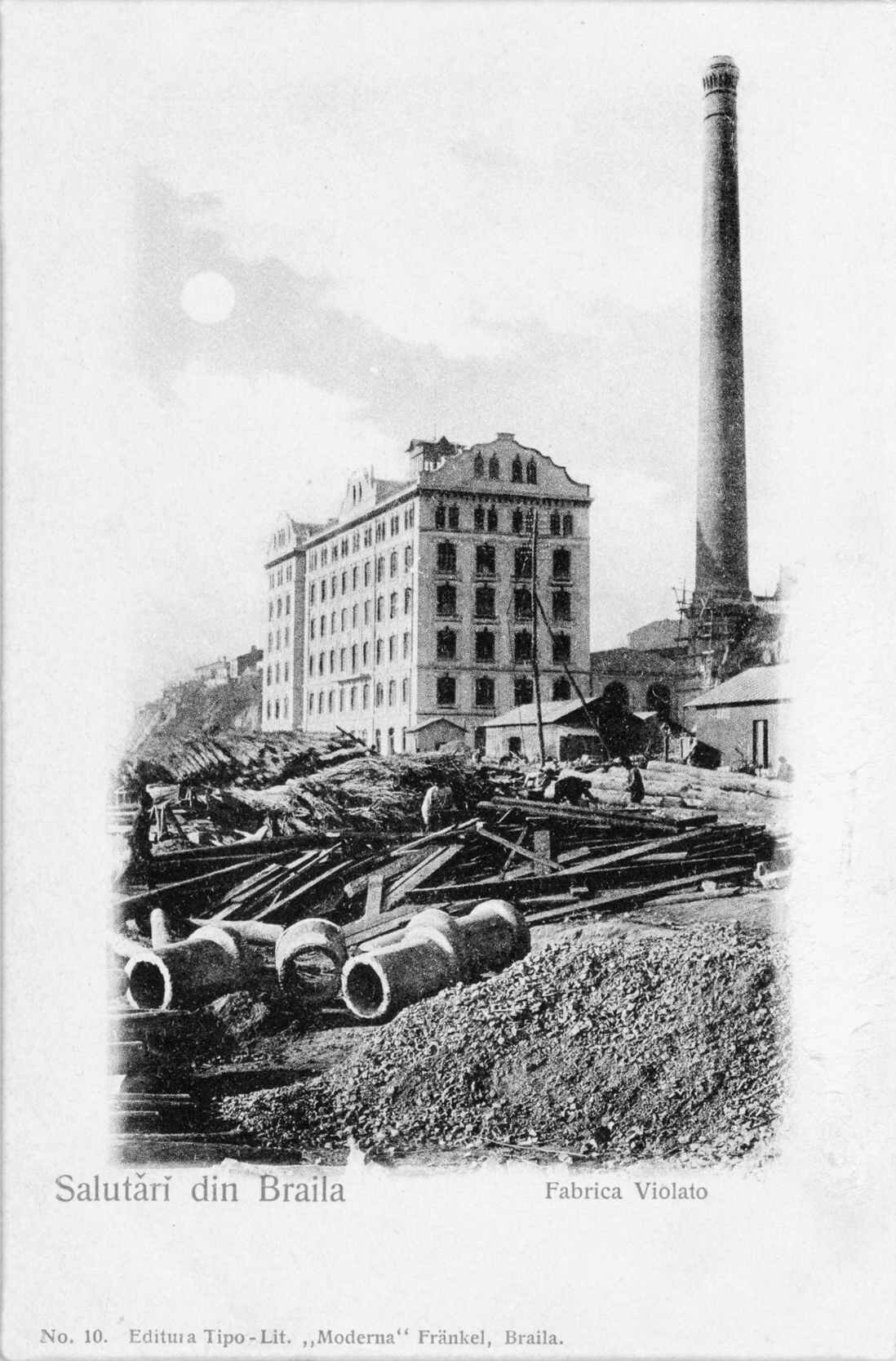

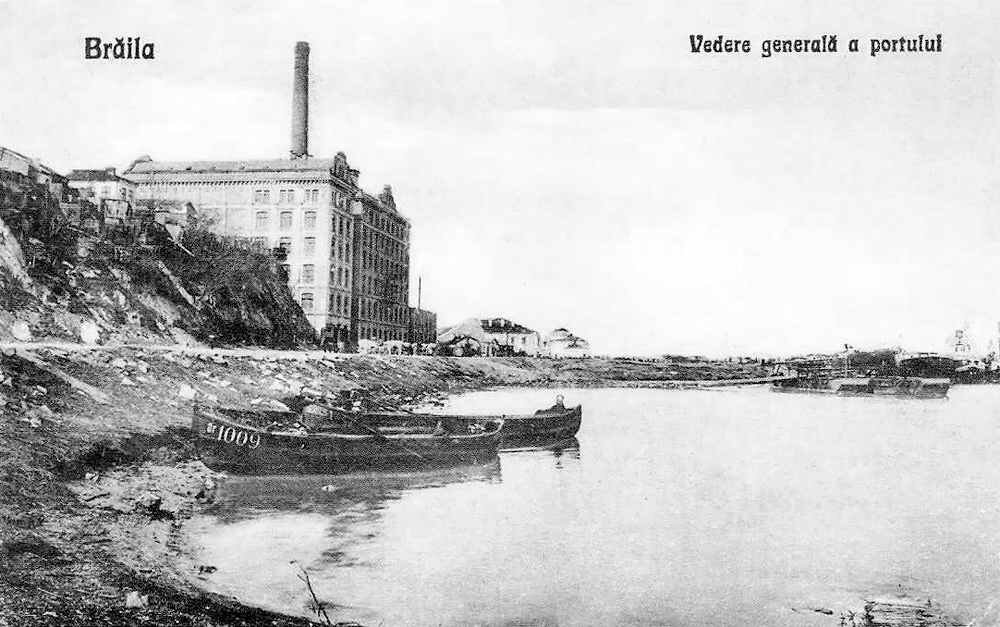

"There are cities for which proximity to water is vital. And not because, nowadays, they are still necessarily dependent on Water (I am referring to a water with a personality - be it a river, the sea or the ocean), as is the case of Braila, where the port, where you can still see the remains of the warehouses built according to Saligny's plans at the end of the 19th century, seems to be deserted, [...] and rarely a boat passes on the Danube, as if the river were dead and led nowhere. Today's Brăila no longer has any direct connection with the water, it's just a provincial market bearing the still fresh scars of decades of communism and forced industrialization, and for most of the locals the Danube is nothing more than a cliff where in the summer, in the heat, it's a few degrees cooler than in the centre [...] for the stranger who arrives for the first time in Brăila and has the impression of going round in circles (an impression partly due to the arc-shaped boulevards, cut by the streets like spokes) until he is seduced by the hypnotic and at the same time desolate air of the city, sniffing the fine scent of mud and fish that the locals no longer distinguish from the domestic, everyday ones, the proximity of the water is fascinating, giving him a permanent feeling of freedom. Water is the guarantee that you can leave a place, but also that you can return. [...] the port, with its famous mills, among which the Violatos Mill, deserted, gloomy, 'for sale'" [...] (excerpt from Adina POPESCU, "Brăila - the city and the dogs", published in Dilema veche, no. 352, November 11-17, 2010).

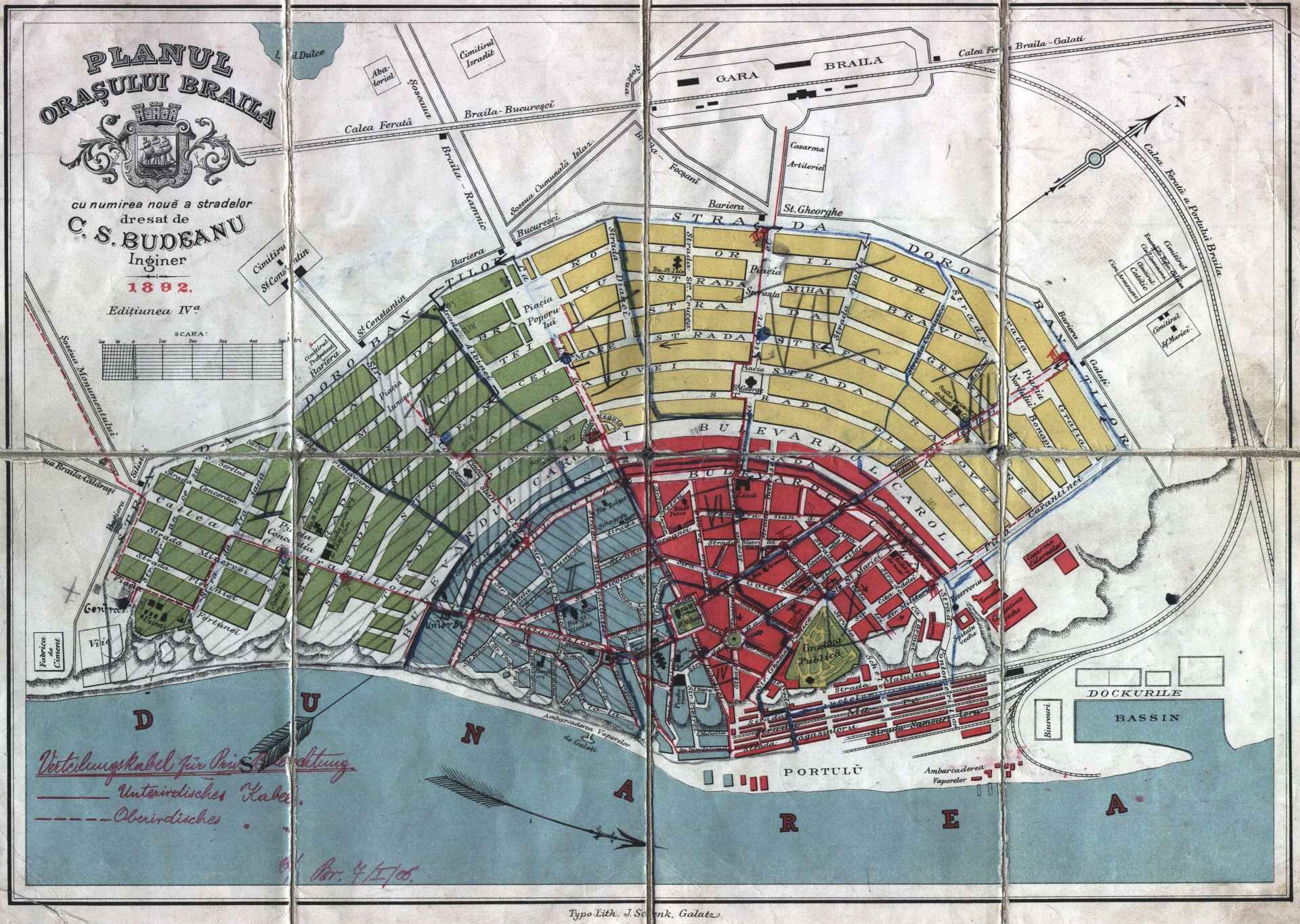

The political stability after 1834, when the Organic Regulation came to an end, the abolition of the Turkish economic monopoly, the development of towns, crafts and trade were the favorable conditions for the development of industry in Braila.

Brăila's internal economic development began in the second half of the 19th century. At that time, the railroad lines were built, the stone quays of the port and industrial and commercial enterprises diversified. Two oil installations were also built on the Danube, one of which was known as "The Principalities Petroleum Refining Company - Brăila" and took part in the Paris International Exhibition of 1867, where, in addition to oil, it exhibited an equally tempting offer of gas and paraffin.

In the same period, the cement factory "I. G. Cantacuzino', a carpet factory, the 'Erevan' clothing factory, a wood-processing factory, a factory for the processing of wood, a factory for the production of spirits, a brick factory and other small enterprises.

Today, only archival documents confirm the existence on the territory of Braila, immediately after its liberation from Ottoman occupation (1829), of pre-industrial technical installations for milling cereals: animal-drawn mills, windmills and watermills. While in 1832 the statistics recorded only 9 mills (5 windmills and 4 horse-powered), three decades later, with the expansion of the urban area and the increase in the number of inhabitants, 219 mills were recorded (140 windmills, 74 animal-powered, two water-powered and three mechanical).

The appearance of the mechanical mills in the second half of the 19th century was a first sign of the beginning of the development of Romanian industry, as evidenced by the appearance in the vocabulary of the word "factory", which was initially the new name for the town workshops where food was produced.

The industrial bourgeoisie developed at a slower pace, but its main initiatives took shape, especially near the port and in connection with its main activity.

Statistics from 1832 show the existence in Braila of three poverne (installations for making brandy or spirits), 9 mills - 5 of which were windmills and 4 horse-powered - and several workshops producing candles and household articles.

In 1860, a report to the Minister of the Interior listed the industries located in the city of Brăila: "A flour, loaves and buckets factory with various machines; two premises for cutting cattle, the so-called zalhanale (slaughterhouses), simple, without machinery; four breweries of which only one is better having the proper machinery and its own premises; a small earthen cauldron for the manufacture of photogenic gas; a few insignificant candles, without instruments that would deserve to be called machines and without their own premises, since the sale of tallow candles is free here, and every citizen is allowed to manufacture this article on his own account by whatever means he has at home."

In 1860, a report to the Minister of the Interior listed the industries located in the city of Brăila: "A flour, loaves and buckets factory with various machines; two premises for cutting cattle, the so-called zalhanale (slaughterhouses), simple, without machinery; four breweries of which only one is better having the proper machinery and its own premises; a small earthen cauldron for the manufacture of photogenic gas; a few insignificant candles, without instruments that would deserve to be called machines and without their own premises, since the sale of tallow candles is free here, and every citizen is allowed to manufacture this article on his own account by whatever means he has at home."

In 1863 the number of factories had increased, although they were modest in size, some of them not exceeding the profile of workshops. The police in Braila had inventoried 38 such factories, set up between 1840 and 1860: "15 factories of brandy (spirits and mastic), with one, two or three ovens with chimney, each with a boiler with one, two or three pipes; 10 bread factories, each with a mill with one, 3 or 4 stones, 6 to 23 horses and an oven with chimney; 2 flour factories with a mill with 4 stones and 18, respectively 16 horses; a macaroni and noodles factory with a mill with one stone and three horses and a machine; 4 breweries with a furnace with one or two chimneys in which the cauldron is placed; a tannery set up in rented premises, where imported hides, ox, cow, calf, horse and dog skins were worked, over 100 pieces in a year, from which iuft and saftian were made; 3 candle factories and a candle and soap factory with two or three furnaces with chimneys in which boilers were placed; a printing press with two presses working in a rented premises". All these factories employed 225 workers, 63 of them at the bread factory of the Italians Borghetti and Gerbolino.

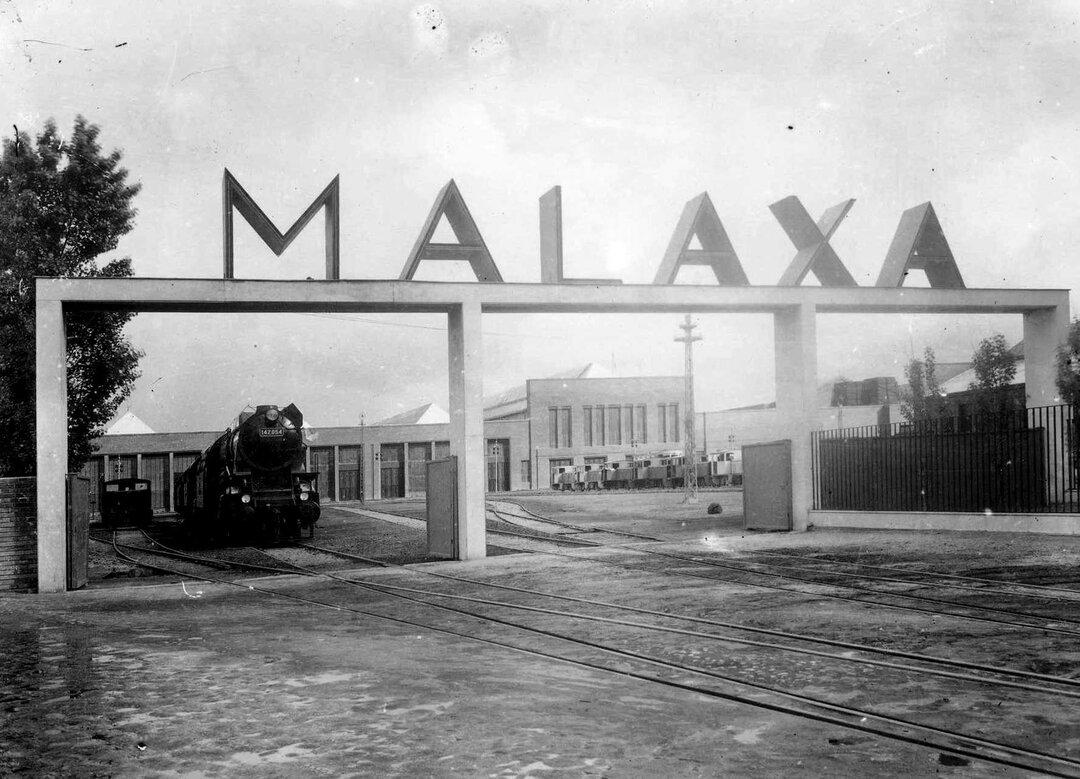

Braila's "steam-powered mills", former and current landmarks of the city's identity

The first mechanical wheat-grinding mill, called a 'steam mill' because it used steam power, was part of the equipment of the Borghetti and Gerbolino bread factory, built in 1857 on the land between Bulevardul Cuza, the high bank of the Danube and Strada Unirii, and to the north as far as near Călărașilor Road. The Italian entrepreneurs set up an 'industrial complex' in Brăila which, in 1866, also included: five mills with flour sifting rooms, a mechanical bakery for the production of long-life breadsticks, a locksmith's and carpentry workshop, and a laundry with a dryer. The plants were served by two Watt steam condensing machines and a pump that directed the water to the plants. The productivity of the machines and the quality of the products were well known in the capital, and in 1860 the owners were approached to set up "a steam mill and two mechanical kneading machines" in Bucharest. At the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1867, Borghetti and Gerbolino took part with products (flour and breadcrumbs), which were awarded Honorable Mention, and with designs for factories.

The Galiatzatos flour factory, established in 1875, was located on Roșiori Street, near the intersection with Victoriei Street. After the extension in 1908 and the construction of the railroad line linking it to the railway station, the mill reached a milling capacity of 20 wagons per day. The Galiatzatos brothers contributed the Galiatzatos brothers to the joint-stock company 'Romanian Mill', which was bought in 1938 by the industrialist Sever Herdan.

The Millas flour mill, located at the intersection of Independence Avenue and Unirii Street with Galați Street, was built in 1879 and was equipped with English-made milling machines. It comprised several buildings: a ground-floor building for the administration, a ground-floor and first-floor building for the flour warehouses, and the mill and the cleaner were housed in two other buildings, with three and five floors respectively, aligned along the edge of Unirii Street, with the building on the courtyard side containing the machine room, the ovens and the mechanical workshops.

Most of the flour produced here was destined for export. At the International Exhibition in Paris in 1889, Iani Millas was awarded the Diploma of Distinction and the Silver Medal for the quality of his flour, and King Carol I awarded him the Romanian Crown in the rank of Officer. Encouraged by his success, the industrialist expanded his business, buying the Borghetti and Lambridini mills.

In 1900, the mill became the property of the Urban Land Credit of Bucharest, and in 1916 it was bought by D. C. Radacovici, who also modernized it. Without complying with the fire safety regulations, the owner built a 22-meter-high wooden cooler and a fuel oil storage tank with a capacity of 20 wagons in the mill yard. Only four years later, in 1920, the mill was destroyed by fire.

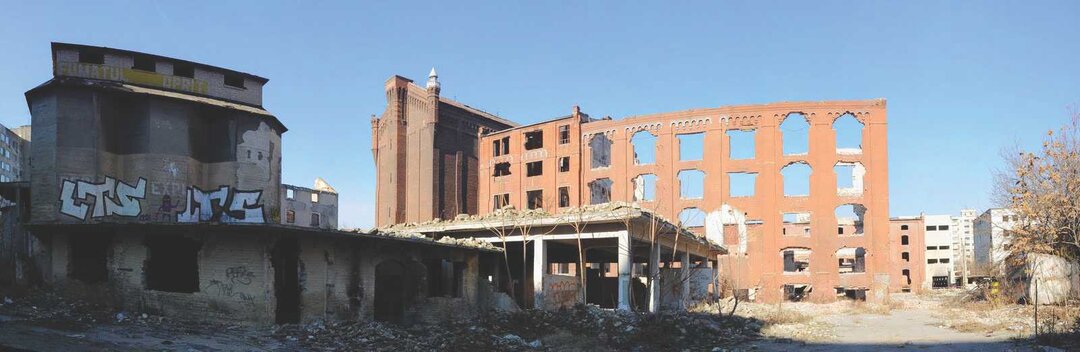

While these mills have disappeared from the urban fabric of Braila, the buildings of two other mills, considered to be the largest and most modern in south-eastern Europe at the time of their construction, have survived to this day in various stages of preservation: the Violatos and Valerianos & Lykiardopoulos flour mills.

Violatos and Valerianos & Lykiardopoulos mills, abandoned historical monuments

Violatos and Valerianos & Lykiardopoulos mills, abandoned historical monuments

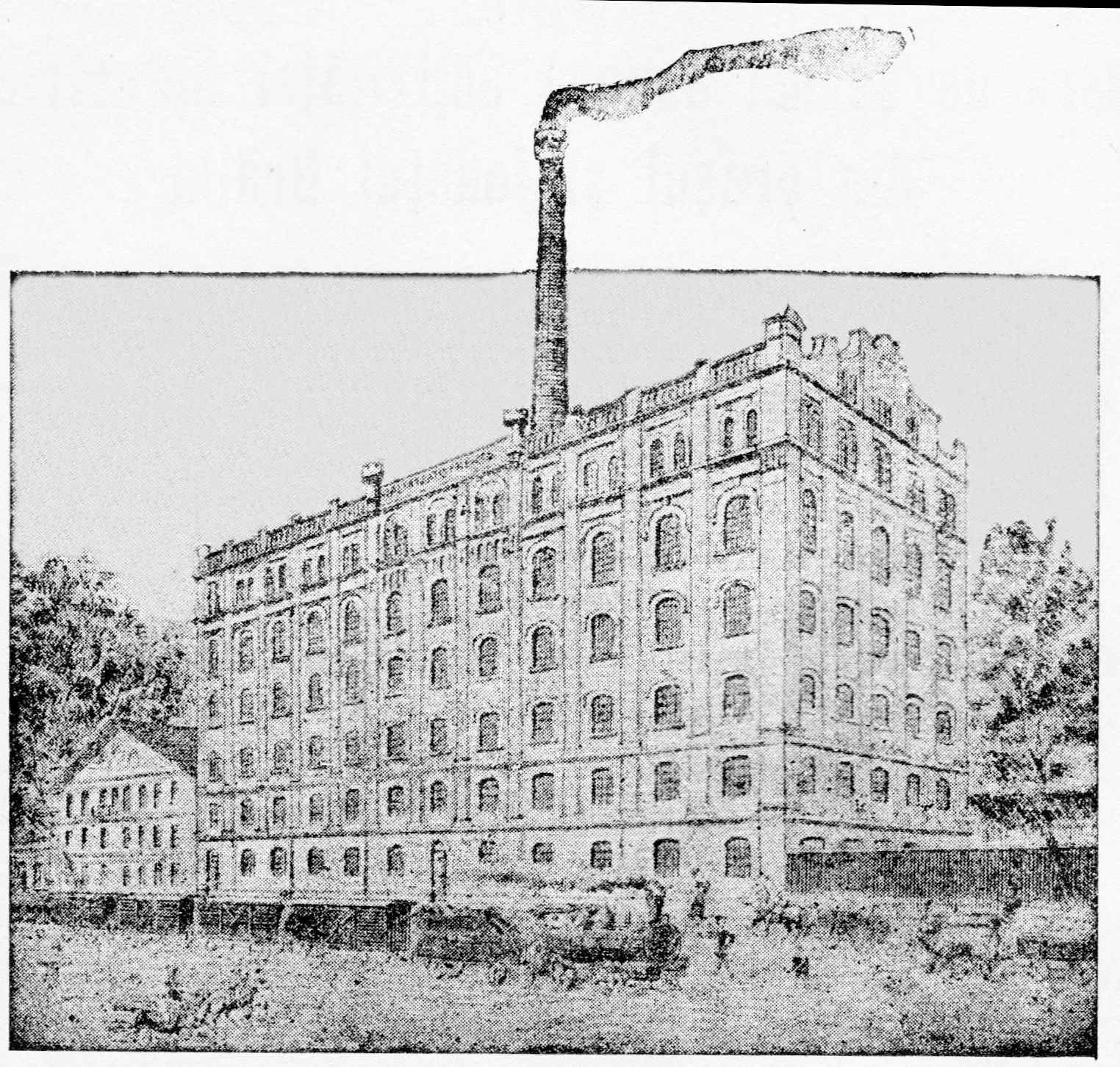

The Violatos Flour Mill (BR-II-m-B-02127 Saligny St. - Violatos Mill 1898) was one of the most famous flour mills in Europe. Panait Violatos was, between 1889-1892, a partner in the Millas Flour Mill, which was awarded a silver medal at the Paris International Exhibition. He then embarked on the ambitious project of building the most modern mill in south-eastern Europe with a large production capacity. The Panait Violatos Flour Factory was built in 1896 on the Danube bank, without the approval of the councillors and despite the interpellation made by Senator Butărescu in the Romanian Senate about the violation of the sanitary law in the case of the location of steam mills on the Danube bank. The mill located in the port had six levels, two of which were occupied by colossal warehouses of flours of all qualities, being connected to the river by an underground tunnel, where a mechanical installation ensured the unloading of cereals from barges directly into the factory. Electricity and engines brought from Braunschweig enabled continuous operation. Chief mechanics and millers were brought in from abroad.

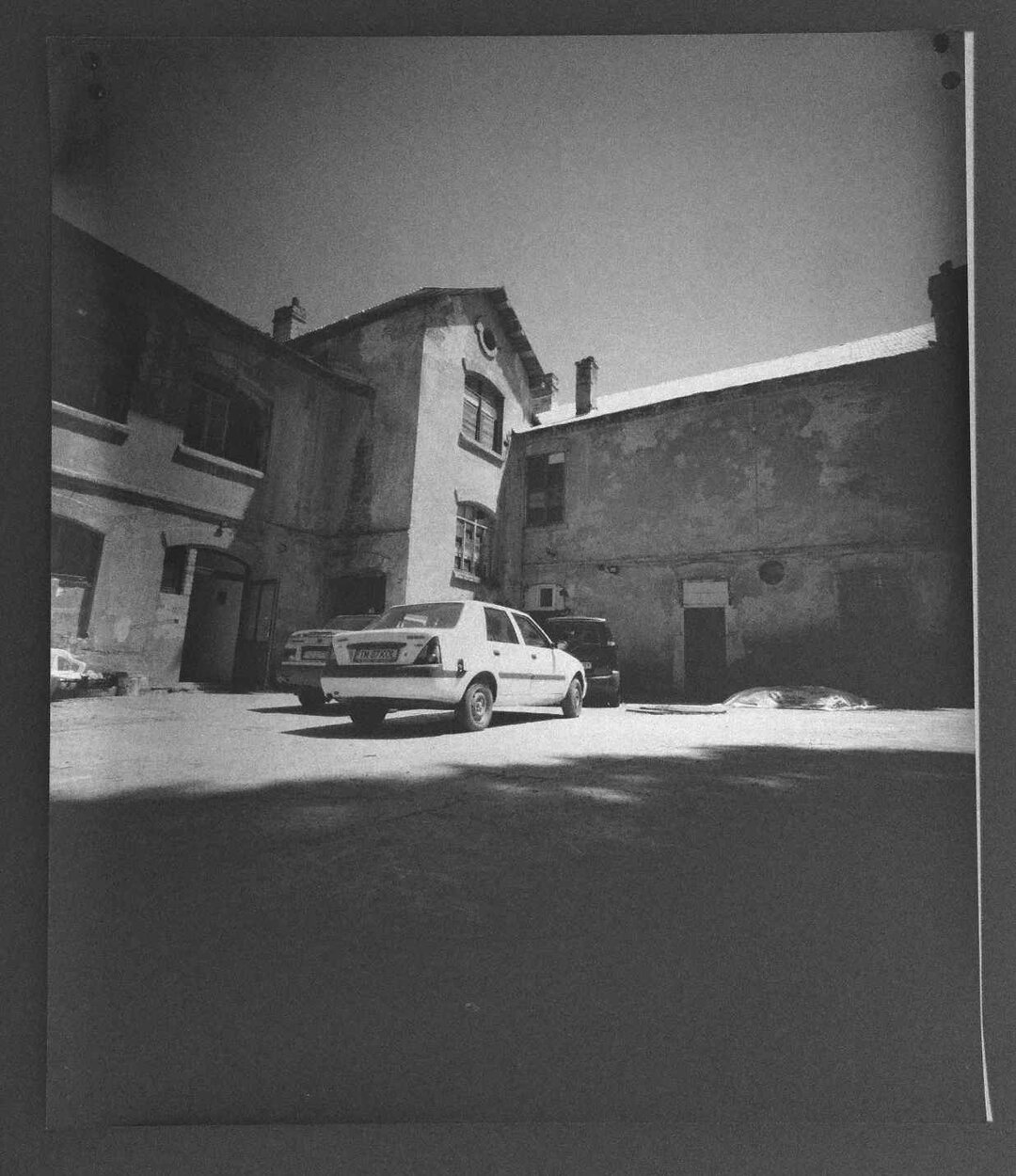

Thanks to the Gottlieb Luther engine (imported from Braunschweig/Germany) with 1,000 horsepower and electrification, production could continue uninterrupted, producing up to 150 tons of flour per day. In June 1948, the industrial assets of the Violatos Mill, which had been seized by the court, became state property. The building was dismantled, but other uses were assigned to it, keeping it in the economic circuit until 2000.

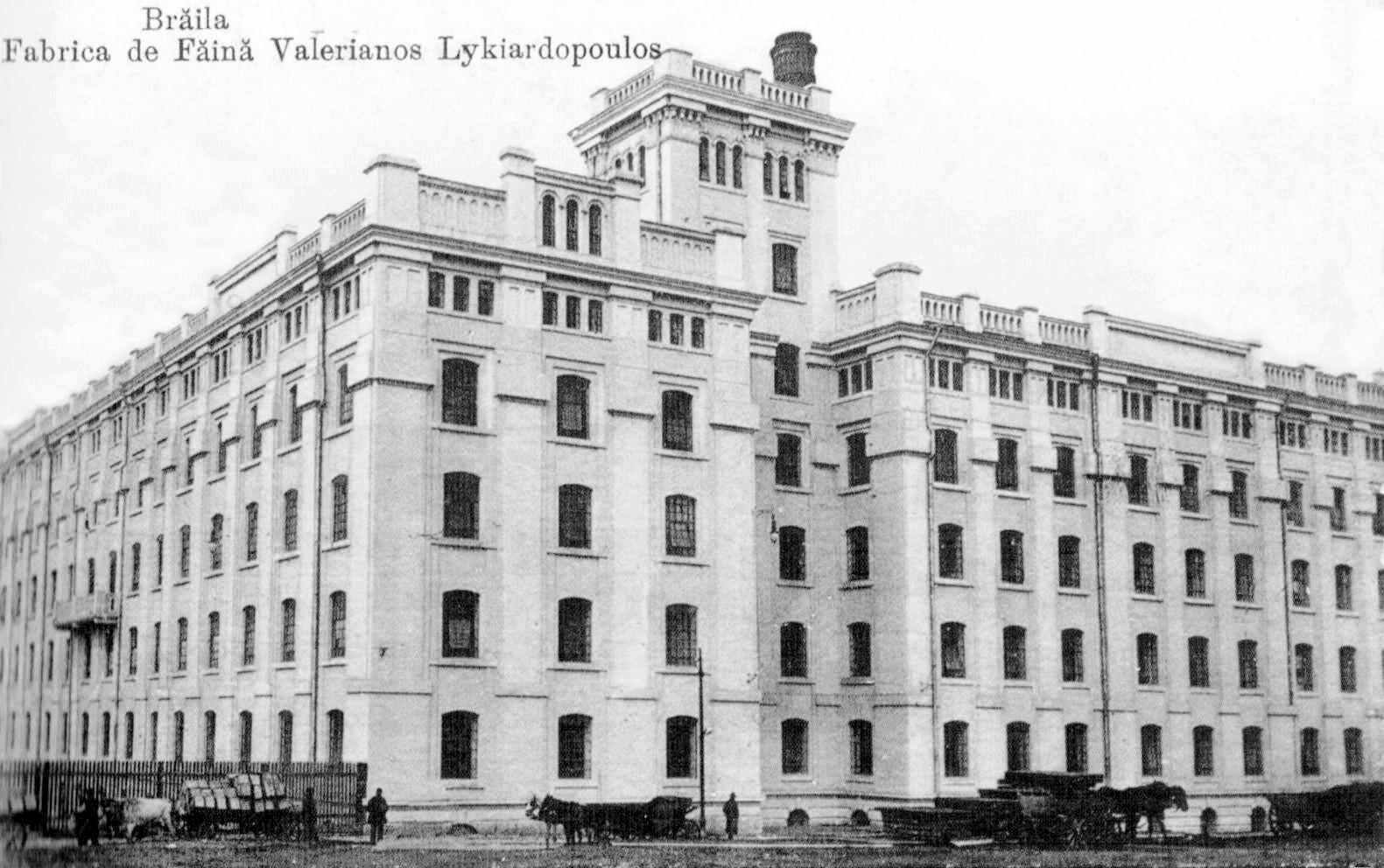

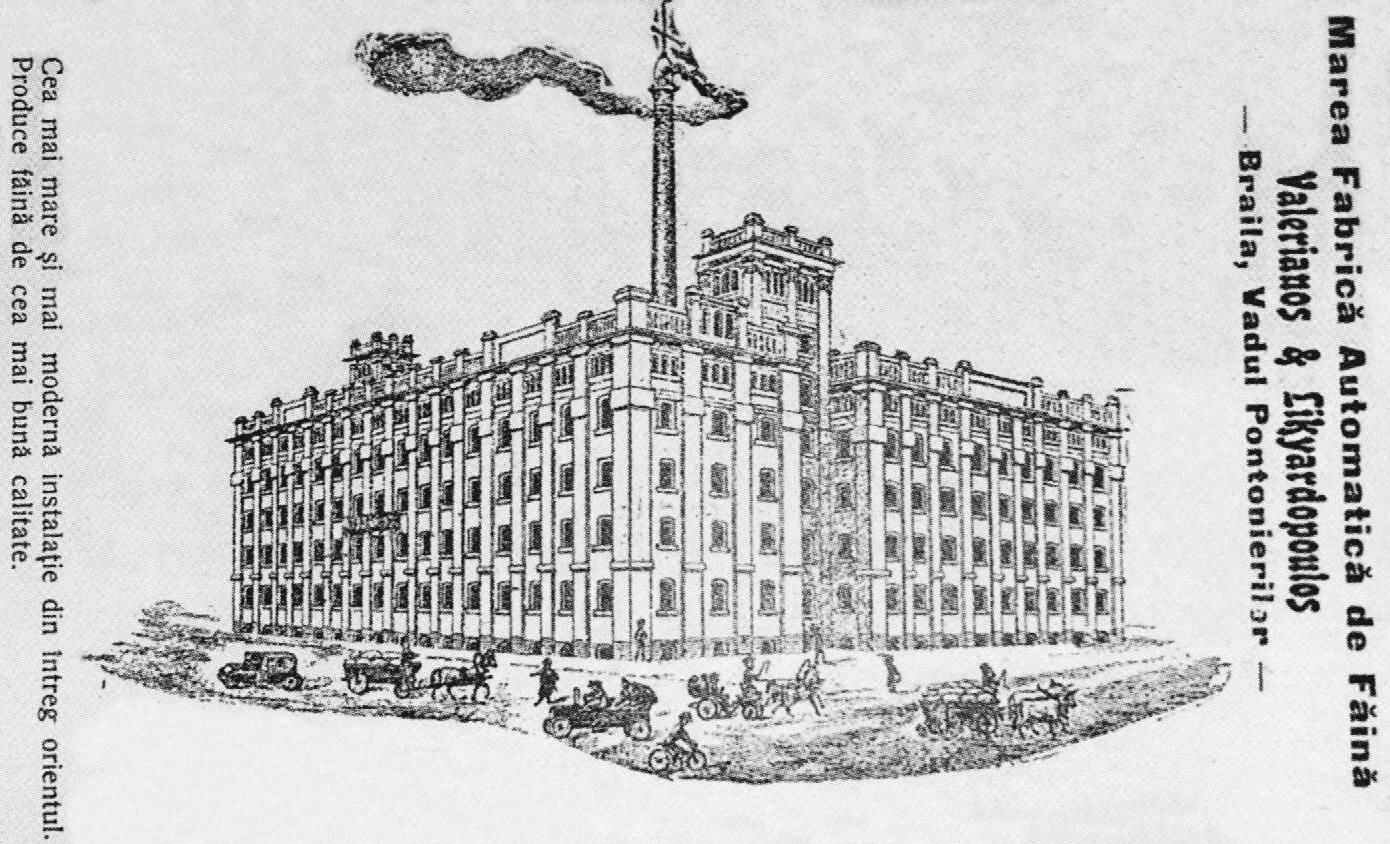

The Valerianos & Lykiardopoulos Automatic Flour Mill (BR-II-m-B-02133 2 Vadul Rizeriei Str. - Likiardopulos Mill 1911-1912), located near the docks, was put into use in December 1912. It was considered to be the largest and most modern mill in the whole East. The monumental five-storey building, consisting of articulated bodies as separate volumes, occupies an area of 11,000 square meters. At its inauguration, it had a motive power of 1,200 horsepower and a plant capacity of up to 40 wagons of wheat per day. Most of the high quality flour production was exported to Turkey, Greece, Algeria, Egypt. The Valerianos & Lykiardopoulos automatic flour mill consolidated, through its technical performance and the quality of its products, Braila's pre-eminence in the flour industry.

After nationalization in 1948, the company continued to operate under the name of the Nicolae Balcescu Bread Factory, employing around 1 200 people at the time of privatization. Its decline began after 2010 and the current state of the building is approaching collapse.

The choice of location for the two establishments on the Danube and the monumental scale of their volumetry, although dictated mainly by economic reasons, were subordinated to the symbolic function of representation. Seen from the Danube, the mills impressed by the solidity and grandeur of their architecture and created the impression that the whole city was growing out of their substance. They visually glorified the prosperity of the city and placed it suggestively under the sign of wheat.

The modern mills had no counterpart in the bakeries, which remained in a primitive state of operation in unsanitary premises: "The so-called laboratories of the bakers in Brăila are small, filthy rooms, without air, without light, with dirty walls and floorboards, serving as a place for the servants to sleep after work is finished. The stables of the horses are usually situated in the immediate vicinity of these laboratories". The first systematic bread factory, Ancora, was inaugurated in 1913 in its own premises at 8, Schelei Street.

***

Bibliography

Maria STOICA, Brăila. Memoria orașului, Ed. Istros, Brăila, 2009

Actualizare Plan Urbanistic General Municipiul Brăila, STUDIU DE FUNDAMENTARE PRIVIND SITUAȚIA ZONELOR INDUSTRIALE AFERENTE FALEZEI, ETAPA I + II + III, Cap. I.2.2. BENEFICIARY: U.A.U.U.I.M. - C.C.C.P.P.E.C., DEVELOPER: INCD "URBAN-INCERC", URBANPROIECT BRANCH, PROJECT HEAD: arch. Doina Bubulete, January 2012