Playing with sheets of glass

Since its invention, it has taken three thousand years for glass to establish itself as a building material, i.e. to help separate spaces. But when it did, it did so in a masterly way. The stained-glass windows gave the revelation of a space beyond the cathedral's spatial limit. But also beyond the spatial limit of our world, because the Gothic windows did not allow the viewer access to the outside through the physical transparency of the glass, but suggested a world magically illuminated by the word of the Lord, through the other meaning of the notion of transparency. This second meaning is the capacity of architecture to allow consciousness to penetrate through its organizational layers and discern its messages.

In fact, we suspect the medieval builders - men like all architects - that, with the realization of large voids, they would have been tempted to create a mundane transparency, at least to daylight, if the technique of glass did not allow the contours to be clearly visible without distortion. Perhaps it was only the mystical imperative, to which the beneficiaries responded, that colored the glass and thus perverted reality into phantasmagoria. But what the medieval builders failed to achieve - the simultaneous perception of several real spaces - was achieved several hundred years later.

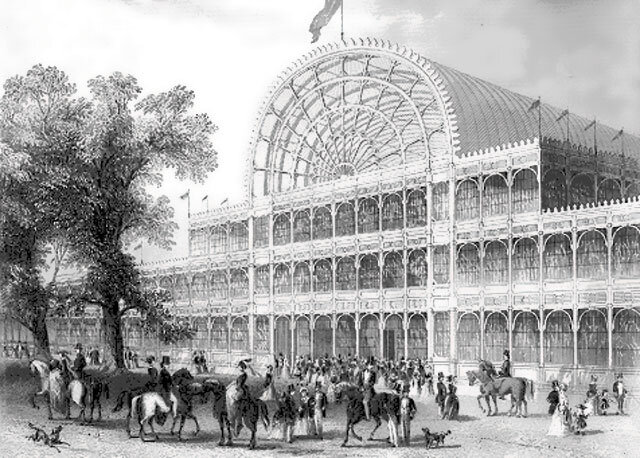

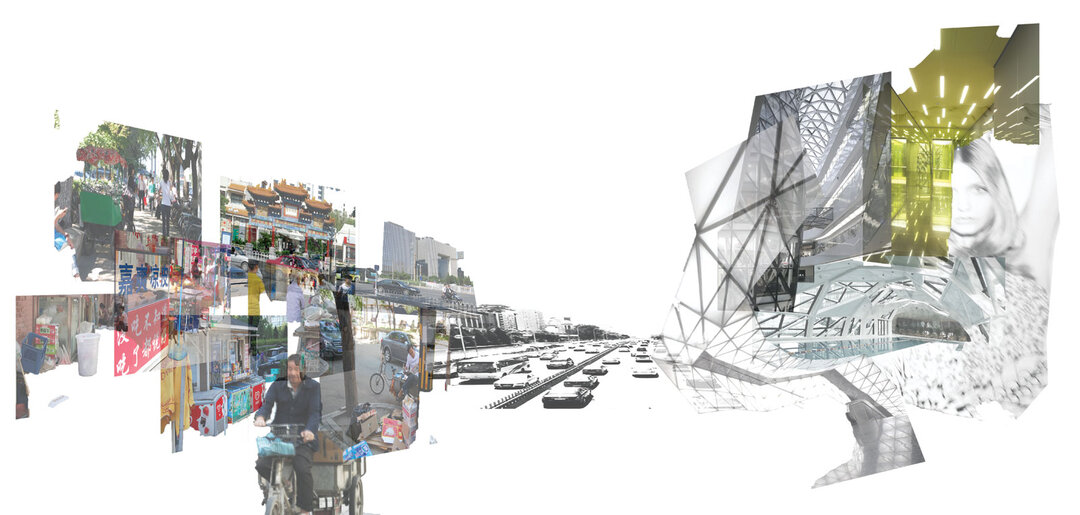

The euphoria of transparency, in the literal sense of the word, began with the vast metal-framed glass umbrellas of the Victorian era of industrialization. Greenhouses, train stations and crystal palaces encompassed a world without isolating it. It was no small thing, and I don't just mean technically. Replacing the opaque boundary with a transparent surface and associating it with light not only allowed communication between inside and outside, but also created a sense of dilation of space.

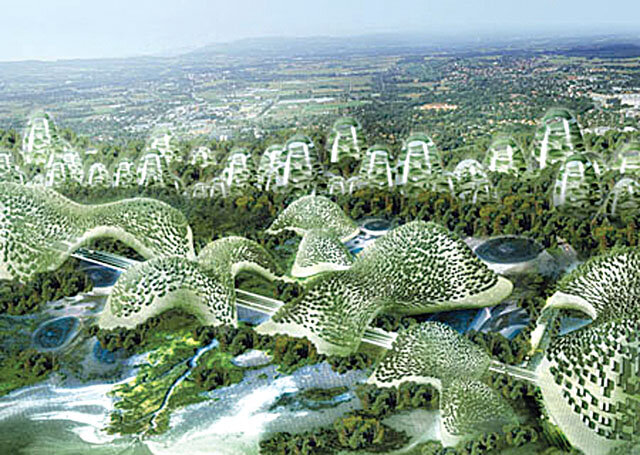

However, the absolute triumph of transparency in architecture, especially as a denotative value, was due to the modernist era. The expressionist architecture of colored glass also belongs to the beginnings of the modern era, which flickered for a while, but which, individualistic, playful and connotative as it was, soon died out, having lost its place in a Europe dramatically hit by crises. Invented by Bruno Taut in 1914 at the Glaspavilion and imaginatively developed by the visionary poet Paul Scheerbart, it was then integrated into neoplasticism and inconsistently courted by Le Corbusier. From its arsenal of meanings, the nostalgia of the socially meaningful cathedral and the symbol of the crystal disappeared forever, but the frivolous charm of colored glass and Scheerbart's dream of all-glass architecture1 were to be revived at the end of the 20th century.

The victorious trend was set by Gropius in 1911 with the Fagus Factory, followed by the Dessau curtain wall. Scheerbart, the poet, had dreamed of interiors bathed in moonlight and sunlight not just through windows but through entire glass walls. And this is how, in 1925, the all-glass wall became the centerpiece of a new ideology. Transparency had now broken with the artistry and ambiguities of the past and defined itself trenchantly and univocally, once and for all (i.e. by 1975), both in a literal sense and in terms of aesthetic meanings - the latter programmatically missing.

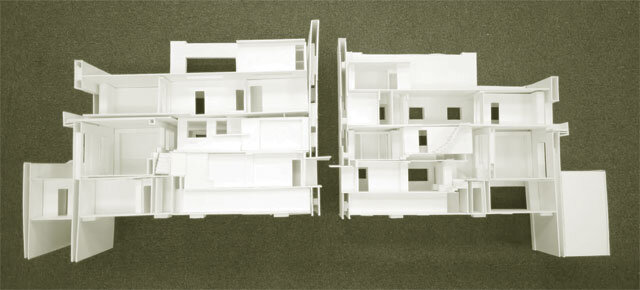

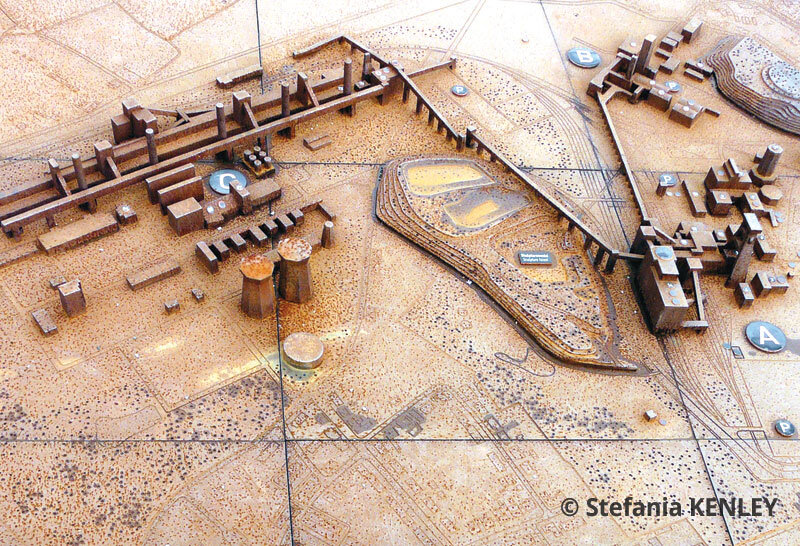

In the literal sense, the new architecture glorified transparency as a physical virtue, backed by the technical prowess of the glass and metal industries. Transparency was not achieved by glass alone, but was favored by lightweight structures with minimized cross-sections. Transparency was also achieved through the interweaving of spaces, the removability of openings, the materiality of light, all of which had the effect of spatial continuity. Interior and exterior could be one and the same space - this is the supreme virtue of transparency. And its ultimate expression: the Mies pavilion in Barcelona.

Read the full essay in issue 4 / 2011 of Arhitectura magazine.

Note:

1 In one of his fictional novels about glass architecture, the hero travels by plane: an exhibition and music center in a Chicago skyscraper, a retirement home for pilots in Fiji, a suspended train in India, a suspended villa in the Kuria Muria Islands off Oman... all made of glass, usually colored.

Anca Sandu Tomașevschi is Conf. Dr. Dr. Arh. at Spiru Haret University and at the Faculty of Constructions of the University of Bucharest.

She wrote the essay column of the magazine Arhitectura for a long time.