The architecture of transparency

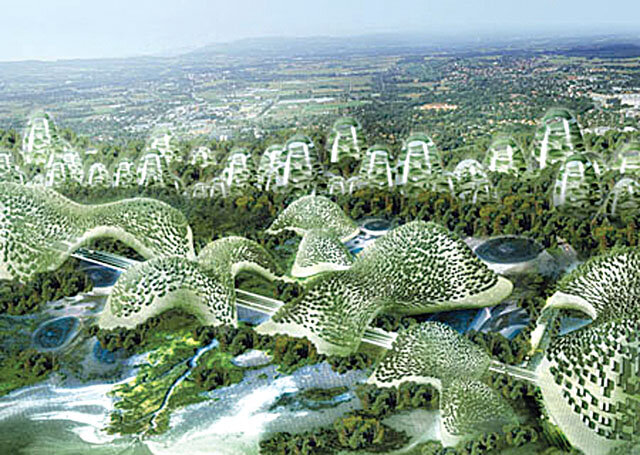

Transparency is a fertile concept in the contemporary recontextualization of the public/private dipole (in its built form). Transparency has not only been an obsessive metaphor for twentieth-century architecture, but, more than that, it has functioned as a new myth of the 'seeing-foreigner', entailing in the process a metaphysics of the beyond; or, as Anthony Vidler inspiringly formulates, 'transparency has opened architecture-as-machine to inspection' (1994, 218). From another perspective altogether, as a myth of social accessibility in relation to the built environment, one has gone so far as to discuss transparency in political terms. Walter Benjamin considered that "Living in a glass house is a revolutionary virtue par excellence" (1978, 180), while Vidler, apparently less radical in the politics of transparency, believes that it is "firmly identified with progressive modernity" (1994, 219). Transparency - the apotheosized metaphor of modernity - is localized to the left of thinking about society and its built environment, while "postmodernism's repressive tendencies towards historical atavism" (219) seem to be exiled to the right1, along with Reaganism and Tachcherism to which it owes much of its fabulous but extremely short-lived (basically, the eighties) breath of life on the scale of architectural history2. Moreover, as the case studies will show, the transparency of buildings indeed functioned as a reflection of the nature of Western and communist societies in the post-war period3.

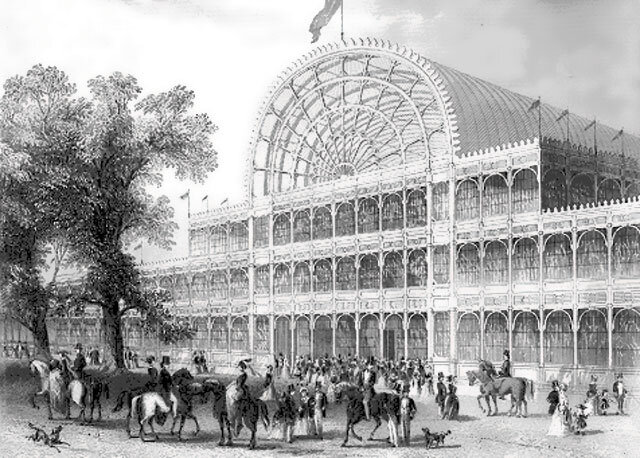

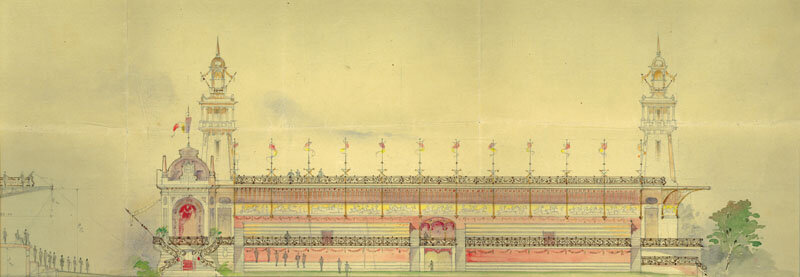

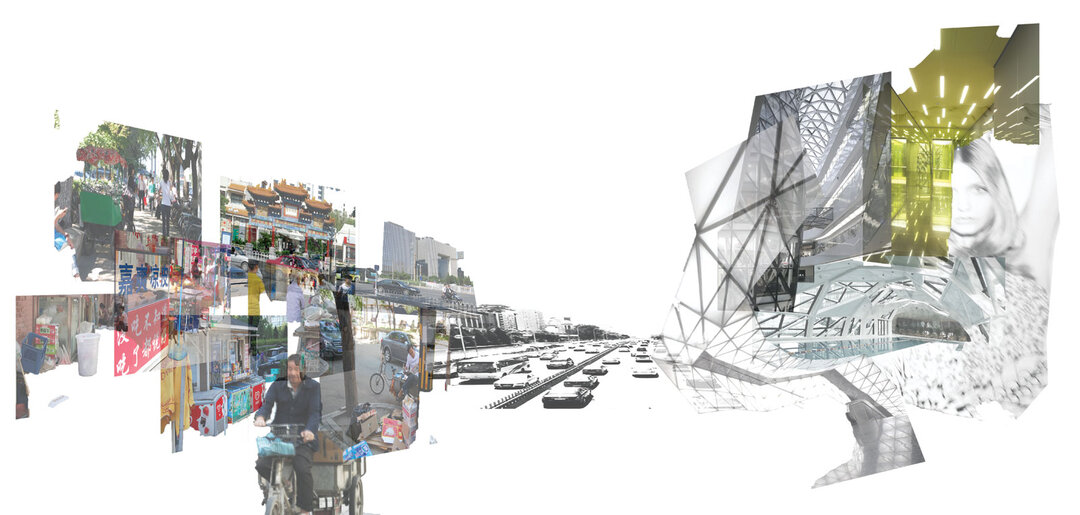

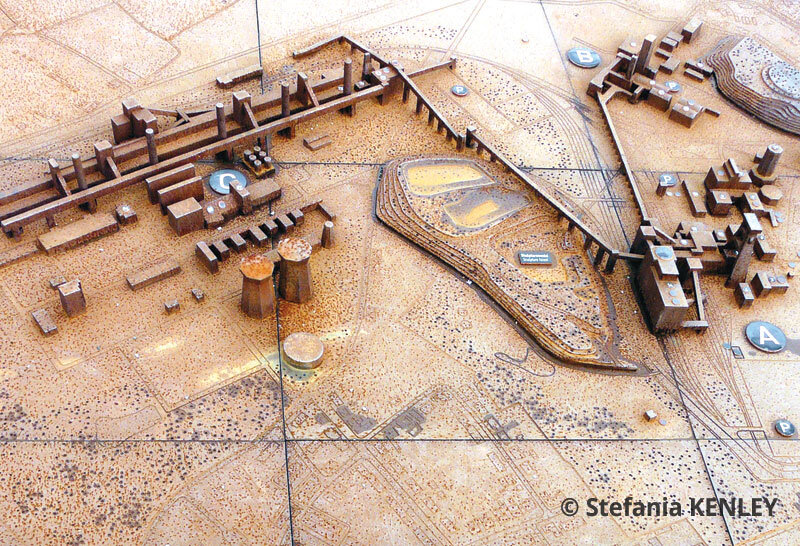

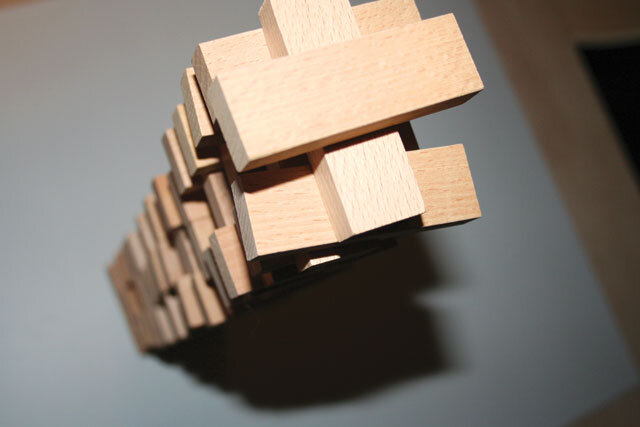

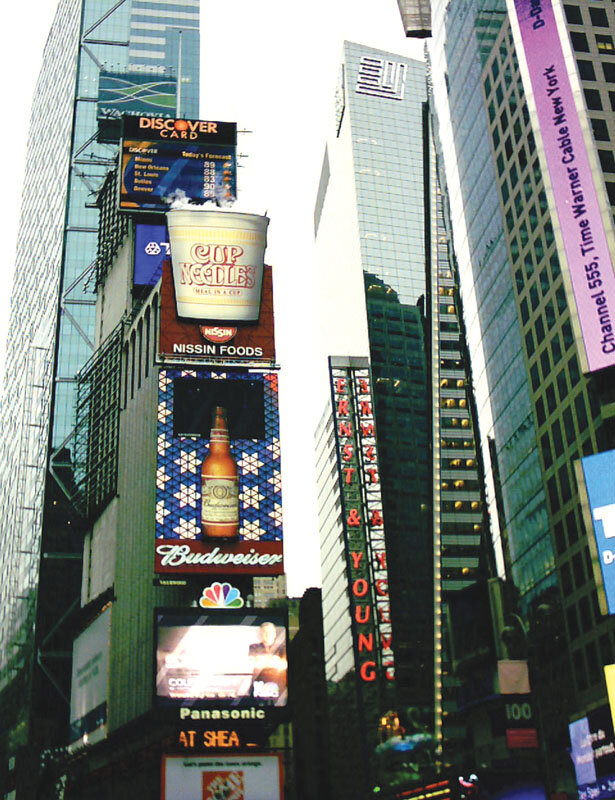

What is of interest in this text is how transparency functioned as a negotiator between the public place and the private space in configuring a built environment. In practice, from Bruno Taut's Glass Pavilion at the Werkbund Exhibition onwards, glass - there used mainly for its spec(tac)ulating effects - becomes a privileged construction material for the entire shell of the modern building façade, not just for its larger or smaller fenestration.

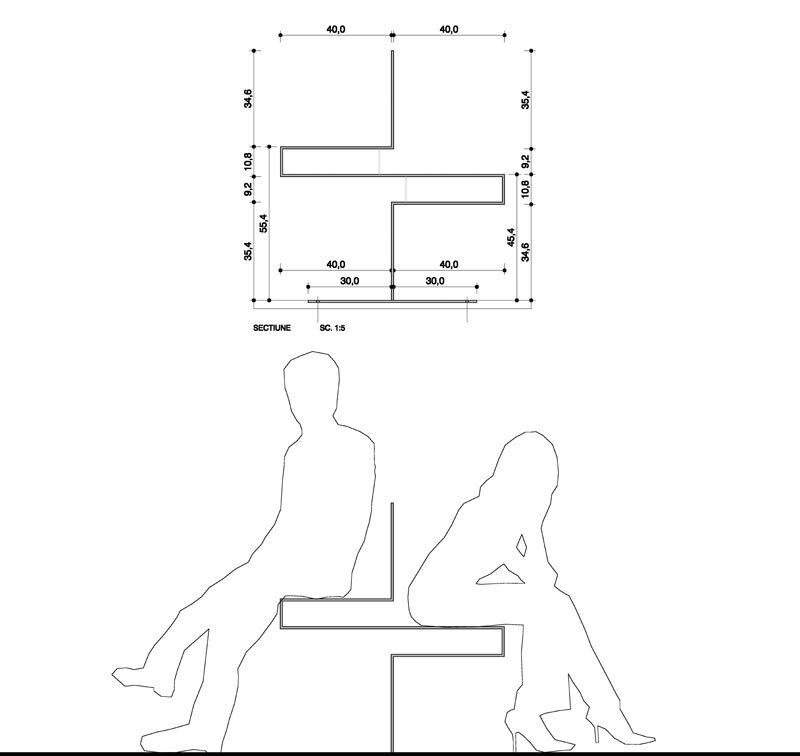

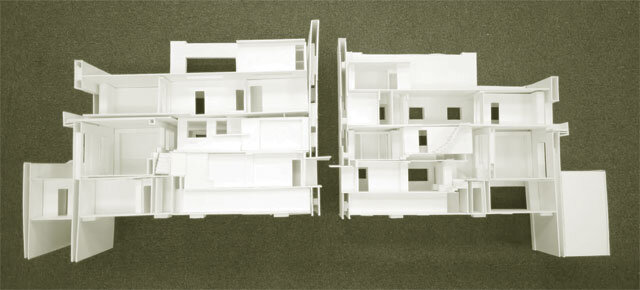

As far as Sp is concerned, glass has tried to suggest (if not succeeded in) a blurring of the dichotomy between interior and exterior; glass could either make 'nature' as visible as possible, which thus became the backdrop for the 'spectacle' of intimate life, or it allowed nature itself to enter the house and take part in intimate life as nature (in Frank Lloyd Wright's houses, and especially in the Villa on the Cascade, where the rock is the living room floor). But, as some deconstructivist theorists have pointed out4, the dematerialization of the exterior facade of the house has often been somehow compensated by the distribution of furniture to this invisible wall, in a somewhat subconscious attempt (by the client in the process of use anyway, if not by the architect himself from the outset) to make up for this weakening of the interior/exterior barrier.

Read the full essay in issue 4 / 2011 of Arhitectura Magazine.