Unidentified Flying Object over Cluj

On October 8 this year, Cluj will inaugurate the biggest and most visible public investment in the last decades, the Cluj Arena stadium. The appearance of this unusual "object" in the silhouette of the city is imposing enough to make us reflect. So, before the euphoria of the inaugural moment engulfs the whole city, there is room for a few mentions.

Cluj's recent history is marked by a strong political image battle in the public arena. Of course, this is a universally valid fact, the public space is the terrain of political expression, but perhaps more than anywhere else here, this battle has primarily involved the surface layer and less the deep, substantive one. The first signs of this phenomenon were the famous tricolor banks. This was followed by extensive archaeological excavations in the Union Square, which were left for a long time uncovered demonstratively to bear witness to the city's Romanianness, in the nationalist spirit of the Gheorghe Funar administration. In recent times the preoccupations have shifted to another sphere and an inflation of festivals, events and celebrations has taken place. The city's public space is the permanent ground for a "special event", celebrations have come to fill most days of the year, being more frequent than the red days of the Orthodox calendar. This permanent need to cover the city's space with events, this festivism, as Ciprian Mihali calls it, is a way of escaping from everyday concerns. "The center lives from celebration to celebration, namely that the noise of popular music and the bustle of the crowds on the terraces and pedestrian streets cover the project vacuum in the rest of the city." It's a butaphoria that masks the everyday problems of the residents, akin to the tricolor spoiel of the first decade after the Revolution. After all, even the construction of a stadium in times of crisis is a manifestation of this kind of festive, circus-like politics for the people. The appropriate expression for this phenomenon is to entertain, which of course has a double meaning, on the one hand in the sense of amusement as part of the ongoing celebration, and on the other hand in the sense of distraction, diversion.

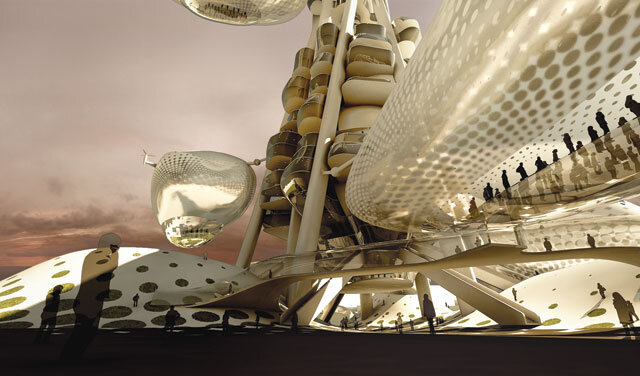

But if we live, as Guy Debord says, in a society of the spectacle, in which marketing has taken the place of religion, then the presence in a city of such an architectural object designed to provide spectacle is absolutely natural. What is more, it is required not only to be a spectacle, but to be in itself a spectacle. This is where the stakes are extremely difficult. By virtue of the functions outlined above and its size, because size matters, the stadium will become an iconic object of the city. He will not be able to miss any brochure presenting Cluj and any tourist guide about the city.

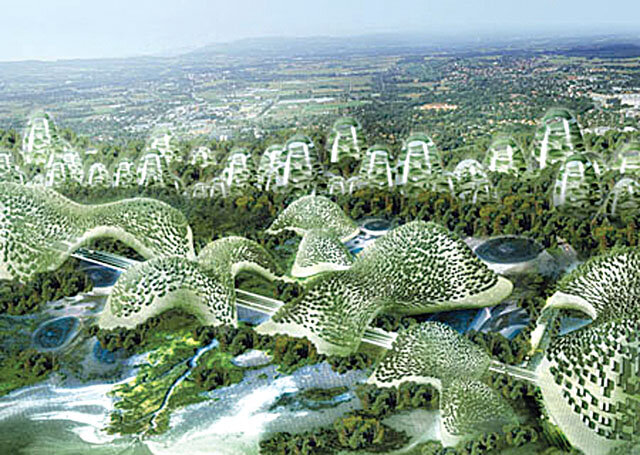

At the turn of the last century, museums played an iconic role in cities. They were the main prestigious investment of a city. Like the theaters of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries or the cultural houses of the 1960s, the museum was the major investment of a prosperous city. It all started with Frank Gehry's Bilbao Museum inaugurated in 1997, which became the modus operandi for any city in search of identity and urban regeneration. It was the piece of architecture that proved that quality architecture can turn the fortunes of a city around, change its destiny. This piece of architecture put Bilbao on the cultural map of the world. But with the onset of the economic crisis, many critics were quick to declare this era of museums over. Of course, in an ageing Europe that looks to its own glorious past rather than to uncertain future prospects, museification is a generalized phenomenon of cities and society. And for a Europe for which tourism tends to increase its share of the budget, it is hard to believe that an architectural program like the museum has reached its heyday.

But even considering that the museum boom period is over, we cannot believe that the era of iconic architectural objects and image vector architecture is over. And then there is the question of what will be the new regenerative architecture for the city. Could sports facilities be the new urban temples? If we are to judge the exorbitant sums of money involved in football by the masses that this sport manages to animate, but also by the influence of football characters who become idols and models of social success, then it seems that football is indeed the new religion, the match - the way of living together, the only possible form of communion in the contemporary world, and the characters involved in football - the new glorified gods. Football stirs up heated passions from western to eastern Europe, even if there is a clear difference between western and eastern fanaticism. While English hooligans see football as a possible outlet in a highly conservative and deeply entrenched society, Turkish fanaticism is the manifestation of a society which is unable to clearly define its values between its Eastern past and its European aspirations. We are geographically and anthropologically closer to the second category.

Therefore, before building stadiums, these temples of contemporaneity, perhaps there was room for establishing values, i.e. building the major cultural edifices that the city lacks. Even before the idea of reconstructing a stadium in Cluj came up, the city was quivering at the thought and the need to build a headquarters for the philharmonic, which had been left without a home. Although today Cluj is aspiring to be the European Capital of Culture in 2020, public money is channeled mainly into sports investments. Construction has already started on a sports hall near the stadium, but cultural projects are still the result of private initiatives, such as the TIFF film festival or the Fabrica de Pensule cultural center. As such, there is a clear discrepancy between the declared strategy and the administration's actual investments. This can be the source of a double failure. On the one hand, the failure to achieve the objective of Cluj - European Capital of Culture, and on the other, the realization of sports facilities incapable of benefiting the city. In Poland's success in being the only country to have avoided the financial crisis, the organization of the European Football Championship in 2012 was very important. This objective committed major investments in infrastructure and buildings, investments which will clearly be recouped later.

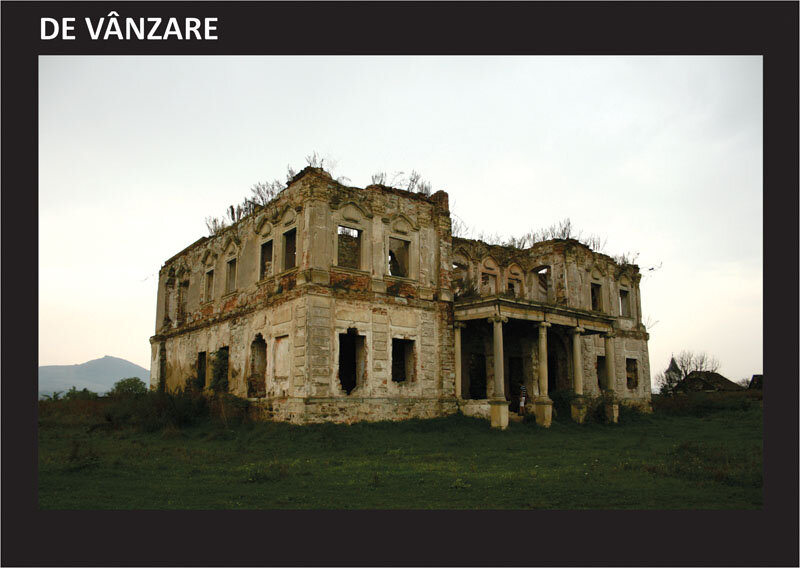

But Romania is as far away from such a goal of organizing a major sporting event to consecrate the new stadiums as the consecration of a church consecrates a building. Therefore, the benefits for the city may never come from the construction of the stadium, leaving only the individual image benefits for politicians.

Just as it may be that, while Romania is bidding to organize a major sporting event, we may find that the existing stadiums are in need of major repairs. Architect Șerban Țigănaș is already bemoaning the fact that ecomonies have been made on the quality of materials. As such, we are still in the realm of spoiel, beyond the spectacular shell and shape lie cheap paints, perishable floors, corrodible materials, which explains why the Cluj stadium is five times cheaper than the National Arena and several times cheaper than a Western stadium. And the cheap refurbishments are likely to raise maintenance costs exorbitantly, so there's no reason to be happy about the money saved.

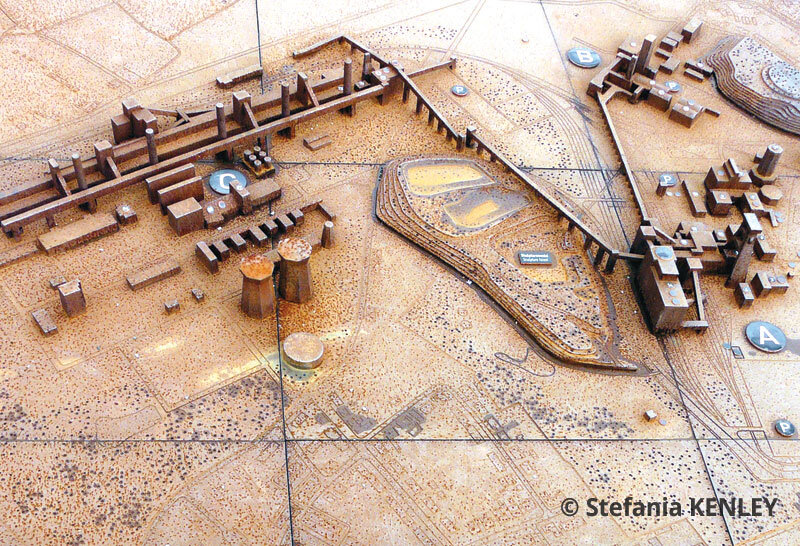

Most criticism of the Cluj Arena so far has been based on urban planning considerations. It has been said that the stadium is an 'object' spoon-holed into a central area of the city, which will create traffic problems, and that if football has become an industry, then the stadium's location is like any other industry - on the outskirts of the city, not on the site of the old stadium built in the era when sport was more recreational. The town-planning discussion is belated, just as the legal action of some architects who, because of procedural flaws in the authorization process, are demanding nothing more and nothing less than the demolition of the stadium, is pointless and ridiculous.

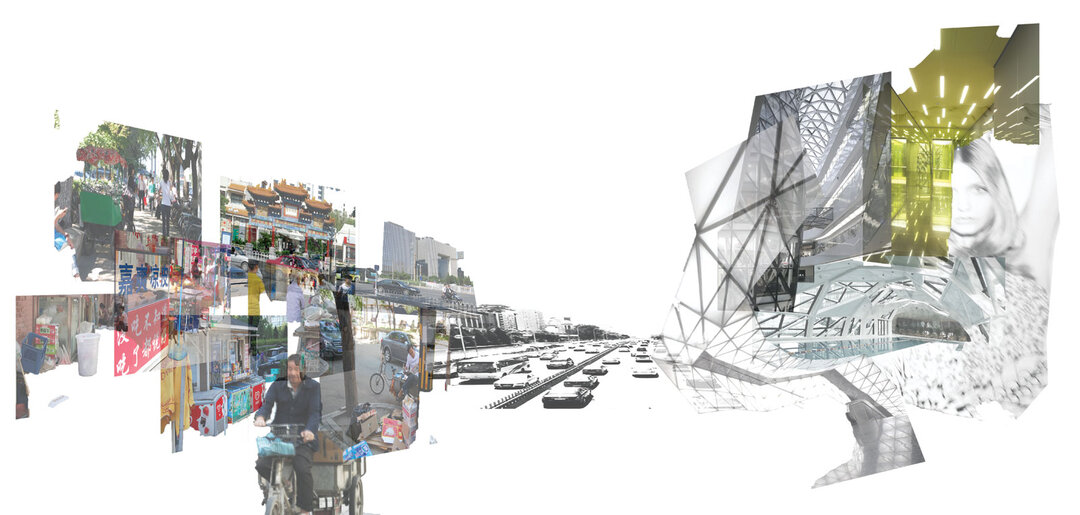

We will have to understand this object through other logics, such as the cynical perspective of Rem Koolhaas, who says that urbanism does not even exist. Urbanism is "pure spectacular ideology. Modern capitalism, which has organized the reduction of all social life to a spectacle, is incapable of presenting any other spectacle than that of our own alienation.

A contextualist critique cannot be applied to objects of such dimensions. Such an object cannot be analyzed in terms of its relation to its neighborhood. Because size does matter, these large-scale "objects", as Rem Koolhaas himself expresses the concept of "bigness", are not subject to a context, but act in "today's global conditions of the race board", they create their own urban context because they are determined solely by the context of economic or political expediency. In other words, if we "indulge in alienation", as Garcias puts it, then it is not the stadium that must submit to the constraints of the site, but the city that must solve the traffic and parking problems generated by the presence of this "object" on the site.

The open day at the National Arena attracted thousands of visitors and waves of excitement. People are exclaiming "wow!" in front of the new stadiums, which impress and arouse admiring reactions. The press is already calling Cluj's new stadium a UFO, and the name is perfectly justified - it's an unidentified flying object, because it's unlike anything that has ever been built in the city. Its size and strangeness are bound to impress and excite. Very soon we will all fall prey to this general excitement as we frantically sing along to the Scorpions' Wind of Chance as an incantation at the opening of the arena. For the wind of change is what it's all about...