Full transparency or some unanswered questions

A FEW UNANSWERED QUESTIONS

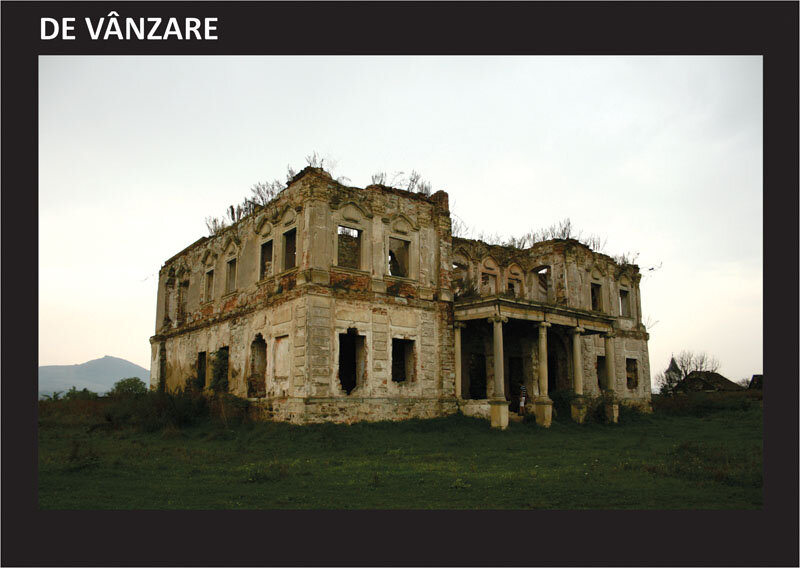

| The noise of the demolitions on the Buzești-Berzei streets has, in recent months, stirred up numerous questions and heated disputes, far from being extinguished, but that's not what we'll be talking about here.Also, University Square is being disrupted by a large construction site for a relatively small underground parking lot, for which four emblematic statues of Bucharest have been moved. They are waiting in Izvor Park to be returned to their original locations and placed in the orderly row that has established perhaps the best-known image of the city center.The four statues, perfectly sized to fit the surrounding built space, were designed on the 1906 building by architect Oscar Maugsch and the 1935 building by architect G. M. Cantacuzino, the parts of the hemicycle which together with the University opposite (1914-1934, architect Nicolae Ghica Budești) determine the most balanced urban framework in Bucharest. The underground remains of the former "St. Sava" Domnești Academy have been demolished here, and the future of the foundations of the church of the same name is uncertain. Less known to the public and even to architects in Bucharest were the tenacious efforts of the Bucharest branch of the OAR to organize, together with the Bucharest City Hall, a competition for the solution for the development of the space on the surface of the University Square. While hopes in this enterprise are not entirely dashed, this case is not the subject of the moment. It is the new construction site opened a few months ago in the immediate vicinity, foreshadowing the imminent transformation of the facades of the National Theater, which raises a number of questions. The story of the National Theatre seems endless, as it has been coming back regularly for more than half a century, and in fact goes back even further, to August 1944, when the old building on Calea Victoriei was bombed. The National Theater's Great Hall envelope, with plaster arches arranged in several registers, was a circumstantial response to a political order in the early 1980s, which was to change the facades resulting from the 1965 project by architect Horia Maicu, in collaboration with architects Romeo Belea, Nicolae Cucu, Richard Bordenache jr. etc. The issue of the National Theatre's refurbishment was the subject of a long series of debates in the 1950s and early 1960s, including public competitions, the most significant of which was the 1962 competition, which was won ex-aequo by the team of architects Anton and Margareta Dâmboianu and the team of architects George Filipeanu and Leon Strulovici. To these was added a spectacular proposal by director and architect Liviu Ciulei in collaboration with architects Paul and Stan Bortnowski. But as is often the case, the project was entrusted to the architect of the day, Horia Maicu, who was also the chief architect of Bucharest, coordinator of the design of symbolic buildings of the communist regime, the Casa Scânteii (1949-1955), the Sala Palatului (1958-1960), the pantheon of communist leaders (1958-1963). The "Maicu" project of the late 1960s proposed a massive architecture dominated by plinths, which in the main hall support a spectacular awning, with contradictory sources of inspiration, recalling both the wide eaves of the Voroneț Monastery and the masterpiece of the architect Le Corbusier from Ronchamp. The ambiguity of the initial solution was also heightened by the very large panels intended to receive an exterior decoration in fresco or mosaic, which did not find its author at the right time. Even if it offered a high standard of conditions for performances, the architectural-urbanistic result was only satisfactory to a limited extent and was the target of much criticism, particularly in the political climate of those years, especially in the corners. Neither was the re-cladding, completed in 1984 according to the design of architect Cezar Lăzărescu, met with positive reviews, especially since the solution adopted reflected the misguided indications of Nicolae Ceausescu, who wanted to cover both the roof of the theater's main hall and especially the stage tower. The works at this stage also affected the interior comfort of the hall, by exaggerating the number of seats and setting up a large official box, implying some risky changes to the resistance structure. With a high degree of wear and tear and a much-discussed architecture, the National Theater building is definitely in need of a fundamental intervention. It would have been expected that such an important subject would have been the subject of a public competition and debate both within the architectural profession and the general public. But things have been quiet. From a few brief articles in the press or laconic TV news, but mostly from rumors, it was learned that the Ministry of Culture had decided to return to the form of the National Theatre from the 1970s, after a restoration project drawn up by architect Romeo Belea, one of the members of the original design team. Apart from the functional and technical advantages of the new intervention, little is known, practically nothing, especially about what the new facades will look like. A couple of questions are insurmountable. It is being demolished, but what will be put in its place? How will the Great Hall's large plinths be treated? But first and foremost, is it appropriate to return to the image of the National Theater of the 1970s? I think not. Its then controversial form cannot be valid today, let alone in the decades to come. In fact, in the string of questions I am asking, it is not so much the National Theater's full house that is the main problem. It is really the unseen, but massive and hard to penetrate, fills that usually surround the information on the conception and realization of important architectural works for redefining the urban profile of Bucharest that make me rejoice. We are building or rebuilding buildings primarily for the future, and it would have been normal for the younger generation of architects in particular to be asked to give their opinion, those who did not have to go through the compromises of the communist period, demonstrating not only great talent, but also a different approach to architecture. How will the space in front of the National Theater be designed? Bucharest City Hall is promising a competition to solve this part of the University Square, which we hope will not drag on like the one in the area of the statues in the immediate neighborhood, which I mentioned above. Would it not have been natural for all areas of University Square to be the subject of a joint study, based on the solutions emerging from one or a series of urban planning and architecture competitions, which would also cover the solutions for restoring the facades of the National Theatre? Instead, materializing an older initiative, a monument dedicated to Ion Luca Caragiale, "The Wagon with Paiațe", by sculptor Ioan Bolborea, was erected in front of the theater. The relationship between this monument and the surrounding built space once again brings to the fore another question, that of the location of public monuments. This situation is illustrated by the chaos of statuary that has been created over the last two decades in Revolution Square. It is also rumored that projects are in the works to transform the Palace Hall and the Omnia Hall, behind the Interior Ministry, the former apparently to become a large "cultural mall", the latter to house the Operetta Theater. All are defining works for the future look of Bucharest, realized with public funds. It would be good if they were known and debated in public, on the basis of solutions emerging from architectural competitions. In other places, in such cases, not only are the solutions the result of public competitions, but there are also presentation points for these works next to the sites of such importance. Unfortunately, this is not the case in Bucharest. We also find out, also by chance, that the Technical Commission for Urban Planning of the Municipality of Bucharest has recently approved a PUZ that allows the construction of a building with a maximum height of 37 meters, which radically transforms the Palace of the former Marmorosch Blank Bank in Doamnei Street, a category A historical monument, built in neo-Romanesque style between 1913-1923, according to the design of architect Petre Antonescu. Basically, according to the proposal currently being approved or already approved, only the main facade, the entrance hall, the waiting room, the monumental staircase and some offices on the first and second floors would remain of the old building. Good or bad? It would be good if the building with its glass-glass-glass facades, attached by 1993 to the calcanque on Eugeniu Carada Street, were to disappear or be transformed. But it is very bad that a monument of the value of the Marmorosch Blank Bank is not preserved in its integrity. And for it, after all, an investor could be found to restore it to its original form, as happened with the palace of the former Chrissoveloni Bank on Lipscani Street (1923-1929, architects G. M. Cantacuzino and August Schmiedigen). Of course, there are other examples we don't know about, and by the time we hear about them, it may be too late. Contrary to the general impression, there is a lot of building going on in Bucharest, and before long we will see that important and traditional parts of the city will look different. How? Who knows. Unfortunately, in keeping with the unfortunate practice of derogatory urban planning, many interventions are based on punctual studies, transposed into zonal urban plans for each corner, which are also modified countless times and of course re-approved according to conjunctural interests, all to the detriment of a coherent overall concept. If we persevere in this way, in the end we will all be left with nothing to do but complain that the city has developed chaotically and without identity. |

| The noise of the demolitions going on on Buzești-Berzei streets has sparked, in the last months, numerous questions and heated debates which are far from over; however, this is not the topic being dealt with here.Also, Universității Square has been ravaged by a massive building site for the construction of a relatively small underground parking, for which four of Bucharest's most representative statues have been moved. They are currently waiting, deserted, in Izvor Park, to be replaced on their original locations, in the orderly succession that has probably become the best known image of the city center.The four statues, whose dimensions are perfectly adjusted to the built environment around them, were forming a semicircle together with architect Oscar Maugsch's 1906 house and with architect G. M. Cantacuzino's 1935 house, which semicircle, in its turn, together with the opposite University building (1914-1934, architect Nicolae Ghica Budești) create the most balanced urban setting in Bucharest. Here, under circumstances whose legality is still unclear for the time being, were demolished the underground vestiges of the former Royal Academy of "St. Sava", while the future of the foundations of the eponymous church is uncertain. Less known to the public and even to the Bucharest architects were the tenacious steps taken by the Bucharest Subsidiary of OAR to organize, together with Bucharest City Hall, a competition for the solution of arrangement of the overground space at Universității Square. Since the hopes associated to this endeavor are not entirely lost yet, we shall not deal with this issue either. Our concern is the new building site opened a few months ago in its immediate vicinity, aiming for the imminent transformation of the façades of the National Theater, which raises a lot of questions. The story of the National Theater seems never ending, and has been regularly brought into focus for more than half a century, if we take into consideration the moment August 1944, when the old building on Calea Victoriei was bombed. The covering of the grand hall of the National Theater, with its plaster archways arranged on several registers, was the incidental response to the political order given in the early 1980s, which aimed to change the façades resulting from the implementation of the 1965 project drafted by architect Horia Maicu in collaboration with architects Romeo Belea, Nicolae Cucu, Richard Bordenache jr. and others. The issue of the renovation of the National Theater has formed the object of a long series of debates in the 1950s and in the early 1960s, as well as of several public contests, the most significant of which was apparently the 1962 contest, won ex-aequo by the team formed of architects Anton and Margareta Dâmboianu and by that formed of architects George Filipeanu and Leon Strulovici. In addition, a spectacular proposal came from director and architect Liviu Ciulei in collaboration with architects Paul and Stan Bortnowski. But, as is the case most of the times, the project was ascribed to the then architect of the day, Horia Maicu, who was also the chief architect of Bucharest and the coordinator of several symbolic edifices of the communist regime, namely Casa Scânteii (1949-1955), Sala Palatului (1958-1960), and the pantheon of the communist leaders (1958-1963). The "Maicu" project, dating from the end of the 1960s, proposed a massive architecture dominated by filled spaces, which supported a spectacular canopy in the body of the main hall, drawing on contradictory sources, such as the ample eaves of the Voroneț Monastery and also the Ronchamp masterpiece designed by Le Corbusier. The equivocal nature of the original solution was also increased by the very large panels meant to be decorated on the outside as frescos or mosaics, which did not find their author in due time. Even if the resulting architectural-urban product provided the conditions for the running of entertainment events at high standards, it met the expectations to a very small extent and was criticized fervently, albeit especially on corners, given the political climate of those years. The works for the new covering structure, finalized in 1984 according to the project of architect Cezar Lăzărescu, did not meet with positive reviews either, especially that the adopted solution reflected the inappropriate indications of Nicolae Ceaușescu, who wanted the canopy of the large theater hall and especially the stage tower covered. The works performed at this stage also affected the interior comfort of the hall, due to the exaggerate increase in the number of seats and to the arrangement of a capacious official theater box involving certain risky changes in the load bearing structure. Given its high degree of wear and tear and its controversial architecture, the building of the National Theater definitely requires major interventions. An issue of such importance ought to have formed the object of a public contest and of a debate engaging both the architects and the public at large. But things went on secretively, as usual. From several brief press articles and laconic news broadcast on TV, but especially from hearsay we have learnt that the Ministry of Culture has decided to restore the National Theater to the aspect it had in the 1970s, according to a renovation project prepared by architect Romeo Berlea, one of the members of the original design team. Apart from the functional and technical advantages of the new intervention, very little - practically nothing - is known about the future appearance of the new façades. Several questions simply arise automatically at this point. It is being demolished, ok, but what is it being replaced with? What treatment will be given to the great filled spaces of the Grand Hall? But, first and foremost: how appropriate is it to restore the National Theater to its 1970's image? In my opinion, it is hardly appropriate at all. The appearance of the building, which was controversial even then, can no longer be valid today and even less so in the next decades. We construct or renovate certain buildings especially for the future, and the normal thing to do would have been to call in the young generation of architects, the generation who has not gone through the compromises of the communist period, and who shows not only talent, but also a different approach to architecture. How will the space in front of the National Theater be arranged? Bucharest City Hall promises that it will organize a contest to identify a solution for the arrangement of this part of Universității Square, which, hopefully, will not drag on like the one in its immediate vicinity, in the statue area, referred to above. Wouldn't it have been natural for all areas of Universității Square to form the object of a common study, based on the solutions advanced as a result of one or several architecture and urban planning contests, and which could also have referred to the solutions for the renovation of the façades of the National Theater? Instead, an older initiative materialized: in front of the theater a monument dedicated to Ion Luca Caragiale was erected, "The Harlequin Carriage", sculpted by Ioan Bolborea. The relationship between this sculpture and the surrounding built environment brings once more into focus another issue, relating to the location of public forum monuments. This situation is also illustrated by the chaos created by the placement of statues in Revoluției Square during the last two decades. According to other rumors, work is in progress at the projects for the transformation of Sala Palatului and Sala Omnia, behind the building of the Ministry of the Interior, with the former being intended as a large "cultural mall", and the latter, as the Operetta Theater. All these are defining works for the future aspect of Bucharest, and are carried out from public funds. It would be natural that they should be known and publicly debated, based on solutions resulting from architecture contests. In other places, in such cases, not only are the solutions springing from public contests, but, next to such important building sites one can see billboards which present the works. Unfortunately, this is not the case in Bucharest. We have also happened to learn that the Technical Commission for Urban Planning of the Bucharest Municipality has recently approved a Zonal Urban Plan allowing the construction of a building having a maximum height of 37 meters, which radically transforms the Palace of the former Marmorosch Blank Bank on Doamnei Street, an "A category" historical monument built in the neo-Romanian style between 1913 and 1923, according to the project of architect Petre Antonescu. Practically, according to the proposal which is awaiting approval, if it hasn't been approved already, the only surviving elements from the former building will be the main façade, the entrance hall, the waiting hall, the monumental staircase and several offices on the first and second floors. Could this be good or bad? A good thing is that proposals have been made for the demolition or transformation of the building with mirror façades, adjoined around 1993 to the rear wall giving onto Eugeniu Carada Street. On the other hand, it is very shocking that a monument as valuable as the Marmorosch Blank Bank is not preserved in its entirety. One might find any time an investor willing to restore it to its initial appearance, as was the case with the Palace of the former Chrissoveloni Bank in Lipscani Street (1923-1929, architects G. M. Cantacuzino and August Schmiedigen). Naturally, there are other examples of which we are not aware yet; when we hear of them, it might be too late. Contrary to the general impression, quite a lot is being constructed in Bucharest, and before long we shall see that important areas of the city, areas with tradition will look differently. But how? Nobody knows. Unfortunately, in accordance with the unhappy practice of an urban planning which derogates from the norms, numerous interventions are carried out on the basis of punctual studies, transposed in zonal urban plans for each individual corner; these are modified countless times in their turn and are re-approved depending on circumstantial interests, and everything, to the detriment of a coherent overall conception. If we continue like this, we are bound to end up complaining in concert that the city has developed chaotically and lacks any identity whatever. |

Article taken with some modifications and additions from the newsletter of the Bucharest Branch of O.A.R. Arhitecții și Bucureștiul nr.34/May-June 2011.

Alexandru Panaitescu is Vice President of the Bucharest Branch of the R.A.A.R. Between 1976-1993 he was part of the design team of the Bucharest subway. He was project manager and author of the architectural part of the subway stations "Ing. C. Georgian" (in collaboration with the architect Lia Dima), "Piața Sudului" and "Aviatorilor". He also collaborated in the design of the stations "Piața Unirii-1", "Crângași", "Piața Romană", Depoul Militari and others.