The right to the truth. Architect Octav Doicescu

We welcome the initiative that in the inaugural issue of the new series of Arhitectura, the first "effigy" presented will be of the prestigious architect and essayist G. M. Cantacuzino. In a natural gesture, it was followed by that of the architect Octav Doicescu, a generation colleague, friend and partner in architecture of GMC, for a time, and from 1948 onwards they had diametrically opposed destinies, and posterity appreciated them in many ways totally different.

In the medallion dedicated to the architect Octav Doicescu1, published in issue 2/2011, an extremely luminous portrait is painted, but without the many facets of his figure. The correct presentation of his entire career, in the form of a chronological enumeration, focuses mainly on the works and theoretical contributions of the inter-war period2, a tendency that remains constant in the interview with Adrian Doicescu, the architect's son3. With regard to his work during the communist period, under the effect of Doicescu's unquestionable charisma, the focus is on exonerating him from the responsibility for his involvement in what socialist realism meant in Romanian architecture.

Although in a restricted space such as this one we can only make a very brief and inevitably schematic assessment of socialist realism, it should be recalled that it was not a cultural movement in the aesthetic or intellectual sense, generated by a group of creators in search of new forms of expression, but on the contrary. In fact, socialist realism consisted in the political-ideological action of the communist regime, carried out at the beginning of the1950s, following the Soviet model, which aimed at the total subordination and control of any form of cultural manifestation, constituting one of the main levers through which Romanian society was fractured5. In architecture, socialist realism, used as a form of ideologization of architecture, was combined with the suppression of the self-employed status of architects and their enrolment in state design institutes, as well as other normative and institutional measures that restricted, sometimes to the point of liquidation, the freedom of creation in the field. The implementation of this complex program of the communist regime could only be achieved with the cooperation of a number of figures within the profession.

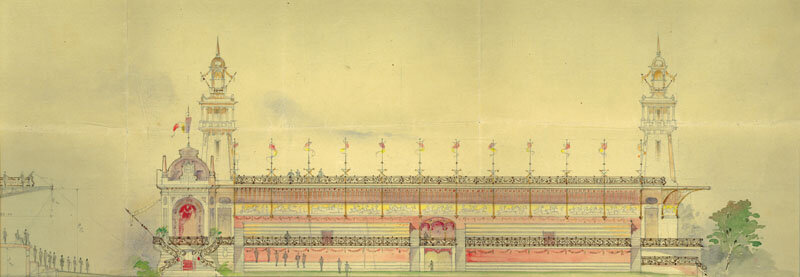

Particularly from 1949, in a general atmosphere dominated by the fear of brutal political repression, which had practically paralyzed the Romanian intelligentsia, out of prudence, more out of necessity and fear, but often out of opportunism or perhaps also out of a more or less naive conviction, many prestigious names of inter-war architecture aligned themselves with the new requirements6, one of these being Octav Doicescu7. In his situation, the ease he showed in promoting the formalism accepted in socialist realist architecture can be considered to have been foreshadowed by the works he had designed in a classicizing register since the first half of the1940s,8 but which reflected a different political context, explicitly illustrated in the 1942 project for the exhibition dedicated to Bessarabia in Chisinau9.

Under these circumstances, the presentation of the complex personality of architect Octav Doicescu is very difficult and full of pitfalls, mainly due to his disorienting career in the 50s, when he continued to be very active professionally10, even though the number of works he produced was lower than in the 30s-40s.

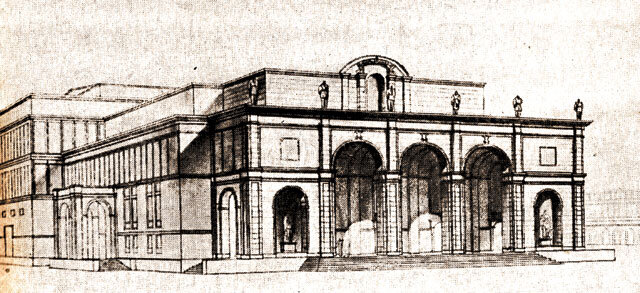

Doicescu's contribution to the promotion of socialist realist architecture is first and foremost the design of the National Opera building11, which he designed in the early 1950s, with the architect's main collaborators being the arch. Paraschiva Iubu, Nicolae Cucu, Dan Slavici and others.

As in the case of the Scânteii House (1949-1955, arch. Horia Maicu, Niculaie Bădescu, Marcel Locar, Mircea Alifanti etc.), the construction of the opera house had to respond to the political commands of the time, which required that it also be one of the emblems of the newly installed communist regime in power, and it is hard to believe that the architect Octav Doicescu did not consciously assume the fulfillment of this mission. The powerlessness of the building made it necessary to establish a relationship of affinity between the architect and the commissioning authority, which was a self-evident condition set by the latter for the achievement of the propaganda aims pursued by the work. The strong personality of the architect Octav Doicescu, proven by his entire career, excludes the possibility that in the case of the Opera House project he was merely a mere executor of the instructions of party activists and/or Soviet advisors. The involvement of the latter in everything that was significant at the time in Romania was commonplace and sometimes even proudly recognized (as in the case of the Scânteii House).12 As regards the Opera building, this fact was publicly signaled from the project's elaboration phase. Thus, arch. Pompiliu Macovei, one of the champions of the promotion of socialist realism in Romanian architecture, in an article in 1952, mentioned that the first studies proposed ... the reproduction of the appearance of a church, the role of the spire on the traditional nave being played by the volume of the stage, and the portico by that of the open porch, common in our churches [....] but as a result of criticism, the help of Soviet specialists [s.n.] and the continuous refinement of studies, a balanced and harmonious composition was achieved... [sic!]13. Even if the quotation is taken from a text written in a wooden language, the account is true, confirmed by the testimony of one of the main participants in the elaboration of the project, arch. Paraschiva Iubu, who recalls the supervision of a Soviet adviser (probably a certain Arch. Zverdin), but also of other political cadres14. In fact, the above statements are to a large extent in agreement with the information in the article in question, but their interpretation is completely different. The sketches mentioned in the article, but not published,15 would seem to illustrate phases of study, more or less inspired by the final outcome of the work. However, no matter how beautifully drawn they may have been, they cannot absolve the architect Octav Doicescu from the responsibility of producing an architecture in line with socialist realism, first and foremost through the general conception of the project, whose authorship has never been contested by anyone until now.

The use of models from traditional architecture, including ecclesiastical architecture, was a practice recommended by the promoters of socialist realism, but it was limited to their mimetic application, consisting of volumetric relationships that were strictly formal or reduced to mere decorative reproductions, without any extensions that could induce political or ideological connotations other than those officially accepted16.

Avoiding the temptation of any deviation17, the architecture of the building for the National Opera followed the recipes approved by the socialist realism culturnicists, who demanded the creation of strictly symmetrical volumes, dressed with classical decorations, amalgamated with elements taken from traditional Romanian architecture. Even if some commentators have praised the professionalism of the author, the Opera's building, built with meagre means in relation to the scale of the program, is basically a product of the socialist realism specific to the Stalinist era, which materialized the slogan of realizing an architecture that was socialist in content and national in form.

It is not possible today to say with much precision how much others contributed to the elaboration of the project, just as it is difficult to know how convinced and sincere the architect Doicescu was in his professional approach, which materialized in the architecture of the Opera building, these aspects remaining at the level of speculation. What is certain is that he was in charge of the project until the end of the works, committing his entire professional prestige to its realization, which is why he was highly appreciated by the communist officials18.

Shortly after the inauguration in the summer of 195319, the main facade of the Opera building was modified in the same spirit, in a solution that emphasized the massiveness of the construction by reducing the portico from five openings to only three. In 1959, the resulting plinths at its extremities received two bas-reliefs (the left one by Zoe Băicoianu and Boris Caragea and the right one by Ion Vlad), and the pilasters between the three central arcades were crowned with allegorical statues, which are of good artistic quality, but these relatively small additions failed to soften the austere impression given by the whole ensemble. Today, the controversial look of the National Opera building has been uninspiringly enhanced by painting its huge plastered surfaces a light green.

Even though until the mid-1960s, when he coordinated the design for the Politehnica, architect Octav Doicescu did not generally have direct responsibility for the design of large buildings, due to the professional influence he enjoyed, he nevertheless played an important role in the direction of many architectural works, including those of a socialist realist orientation (see, among others, the porticoed block in the Roman Square or the Dalles block).

A possible conclusion to the discussion on the involvement of architect Doicescu in promoting socialist realism may also be a statement by G. M. Cantacuzino said in another context, but which is also relevant to the present analysis, namely that... the only chroniclers who do not lie are the constructions... In this sense, the building of the National Opera in Bucharest, more than any text or drawing, is a testimony that is difficult to contradict. It is also a reminder of an era in which Romanian society was totally subordinated to a foreign power, which proved hostile, especially through the ideology imposed by sacrificing modern democratic values, but above all Romanian tradition.

Last but not least, the surprise generated by the way in which the architects Octav Doicescu and G. M. Cantacuzino. By appealing to so-called quantifiable aspects, the scales are tipped in favor of the former because ... he lived about 20 years longer [...] he had, however, more important works and in greater numbers [...] he was a poet of his works and of the organic urbanism he promoted. GMC, on the other hand, is being dismissed on the grounds of social affiliation, ...aristocrat by birth, he damaged his own record worse when his attempt to leave the country failed; he became a political prisoner, his work as an architect having practically ended.... From here to the 1950s label of enemy of the people, which the above quote may suggest, is only a step. For the rest, GMC's multivalent work, even from the years of marginalization in Iași, is dispatched in a few words and seems not to matter very much. Strange, and further comment is superfluous.

The issues raised here should not be seen as part of an attempt to diminish the undoubted merits of the architect Octav Doicescu, but are merely necessary additions to his profile, rich in light, but also having many shadows, which ultimately make him even more worthy of interest. It is certainly necessary to give up presenting great personalities only from the angles that are considered to be advantageous, so that they can later be transformed into myths. The career of Octav Doicescu, who was also a point of reference during the communist period, including the years of Stalinism, had to navigate the complicated and compromising thicket of the era and inevitably took a route that may be contradictory. Knowing and studying it in all its aspects, good and not so good, including the correct historical context, is absolutely necessary in order to build a true portrait of the great architect that he was.

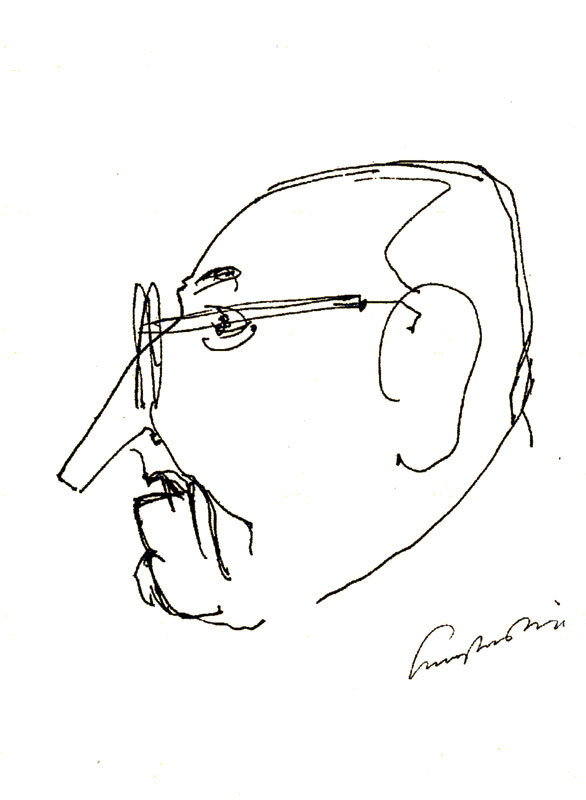

In any case, I propose to admire both the portrait of the architect Doicescu in his youth, as sketched by Marcel Iancu in a well-known drawing dating from 1935, but also to look with the same attention to the one made by arch. Gheorghe Dorin in the 70s.

NOTES:

1 Craft and Art - Prof. arh. Octav Doicescu (1902-1981), by drd. arh. Alin Toma Negoescu.

2 Also, the illustration of the whole article is limited only to drawings by architect Octav Doicescu from the pre-war period (without identification and dating legends) and no image of a work designed by him during the communist period is published. In a presentation of Doicescu's entire activity they were absolutely necessary.

3 Published by the same author in issue 3/2011.

4 In the present article, dates of this kind refer exclusively to the 20th century.

5 See Marin Nițescu's overall analysis of socialist realism, especially in literature, but which in its general approach extends to the whole of Romanian culture(Sub zodia proletcultismului și Dialectica puterii, Humanitas Publishing House, 1995) or Mariana Celac's brief assessments of the changes that occurred after 1947 in the practice of architecture(Timpul fracturii, after the book Despre o estetică a reconstrucției by G.M. Cantacuzino, Editura Paideea, 2010, p.108-109).

6 Many renowned creators who promoted socialist realism in the 1950s, later, since the 1970s-1980s or especially after 1989, would express their belated disappointment with real communism and tried to minimize or even forget this episode in their careers.

7 Octav Doicescu's presumably left-wing political options should also be mentioned in this regard, manifested as early as 1934, when he was a member, along with Prof. Petre Constantinescu-Iași, the sculptor Mac Constantinescu, the writer G. M. Zamfirescu and others, in the association Friends of the USSR, which was run by the PCdR and the Comintern (see in the volume On Marx's Shoulders. O introducere în istoria comunismului românesc, Adrian Cioroianu, Editura Curtea Veche, 2005, p.115).

8 These include the block of flats in Știrbei Voda Street, the office building, formerly Banloc, in Calea Victoriei or the telephone exchange in Banu Manta Boulevard.

9 See in the volume Spațiul modernității românești (coordinated by Carmen Popescu), Editura Fundației Arhitext design, Bucharest, 2011, p.180-182.

10 Unlike other prestigious architects of the inter-war period, who for political reasons saw their careers cut short, as happened with I. D. Enescu, Constantin Iotzu, G. M. Cantacuzino and others. Nicolae Cucu will continue to work after 1950 only as a collaborator of some architects approved by the communist regime, such as Horia Maicu (at the pantheon of communist leaders and the National Theater), but also Octav Doicescu (at the design of the Opera building, where arch. Nicolae Cucu was responsible for the interior decoration and furniture).

11 Originally destined to be a musical theater, which was to eventually belong to the operetta troupe, the opera artists were to use the new building provisionally until the construction of another larger theater. In the early 1950s, plans for another building specifically for opera performances as well as the National Theater were planned to be completed by 1955. The National Theatre was not realized until the end of the 1960s, but in the case of the opera the intention never materialized and like any provisional arrangement it proved to be sustainable, and the National Opera still operates today in the building completed in 1953. The idea of realizing another building for the Opera as well as for the Festival Cântarea României was taken up by N. Ceaușescu in 1987-1989, when a huge construction complex was started on the south side of Unirii Boulevard, approximately in the middle of the section between Unirii and Alba Iulia squares. After December 1989, the works, at the infrastructure level, were abandoned.

12 See the article "On the use of the heritage of the past in the architecture of the 'Scânteii House', arch. Horia Maicu, Arhitectura și Urbanism magazine no. 4-5/1952, p. 9.

13 See the article Probleme de creație în arhitectura RPR, arh. Pompiliu Macovei, Arhitectura și Urbanism magazine no. 9-10/1952, p. 55.

14 See in the volume Arhitecți în timpul dictaturii. Amintiri, Simetria Publishing House, 2005, pp. 152-155.

15 It is certain that, with the support of the Union of Architects, an attempt will be made to fill this gap by publishing a significant selection of Doicescu's drawings, as one of the main actions to mark the 110th anniversary of his birth in 2012.

16 In this regard, see the articles by architects Horia Maicu and Pompiliu Macovei, cited above.

17 As happened in the case of the Radio Broadcasting House in Str. G-ral Berthelot, designed at the same difficult time by arch. Tiberiu Ricci, Mihai Ricci, Leon Garcia, Jean Beral, and whose volumetric cut is more in keeping with the modern architecture practiced in the 30s. In the detailing of the stonework that covers the facades of the tall buildings, it is evident that the solutions used by arch. Duiliu Marcu on the building in Calea Victoriei realized between 1937-1941 for the Ministry of Economy (former headquarters of the Regiei Monopolurilor de Stat). Also in the article in the magazine Arhitectura și Urbanism nr. 9-10/1952, p. 51, arh. Pompiliu Macovei harshly criticizes the Radio Broadcasting House project for ...the functionalist and complicated play of the volumes [...] which directly express the reinforced concrete structure, and the designers were considered to be...cosmopolitan.... Such sins, however, were not detected in the case of the analysis of the design for the Opera House. In order to escape the label of being ...a typical example of formalist architecture..., the portico in front of the concert hall of the Casa Radodiffusion had to be decorated with classical columns crowned with statues, which could later be abandoned due to the beginning of desovietization in architecture. This was also the case with the interior decoration of the public areas of the concert hall, which had been planned in classicized forms, but simplified until 1960, when the work was completed. Even if the treatment of some of the details still makes concessions to the requirements of the time when it was built, the Casa Radiodifuziunii is still one of the most interesting buildings in Bucharest.

18 This fact is evidenced, among other things, by the award of important distinctions, the State Prize and the Order of Labor, as well as by the presentation of the Opera House building at the design stage of the exhibition Architecture in the RPR, which opened in Moscow in the summer of 1952 and which gave an initial assessment of the new socialist architecture in Romania (see Arhitectura și Urbanism magazine no. 9-10/1952, pp. 3-20)

19 The construction was completed in a first stage on the occasion of the Youth Festival in August 1953, which is why the Opera building is usually included among the buildings built for the Festival, the former 23 August Stadium, the summer theaters in the former 23 August Park (today's National Park) and Nicolae Bălcescu Park (today's Bazilescu Park) and the Cinema of the Brotherhood between Peoples (today's Masca Theater), all of which are considered notable illustrations of socialist realism in Romanian architecture.