Avangarda ca viziune dincolo de vizibil

The avant-garde as vision behind the visual

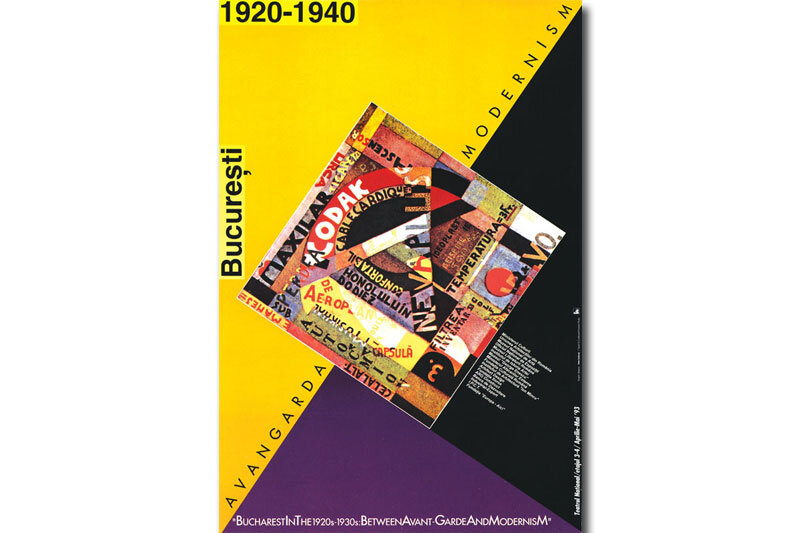

| La începutul secolului al XX-lea, mișcările de avangardă aveau un profil clar definit: un grup de artiști novatori, cu unul sau mai mulți reprezentanți și cu un manifest provocator. Deși mult controversat la vremea aceea, subiectul face astăzi parte dintr-un capitol închis al istoriei artei moderne, deja analizat, clasificat și asupra căruia toată lumea este de acord. În 1955, când Reyner Banham a scris articolul „Noul brutalism” (The New Brutalism), în revista Architectural Review, a făcut distincția între două feluri de grupări: „Una, cum ar fi Cubismul, este o etichetă, un semn de recunoaștere, aplicat de critici și istorici unui ansamblu de lucrări care par să fie unite de anumite principii consistente, oricare ar fi relația între artiști; cealaltă, cum ar fi Futurismul, este un stindard, un slogan, o politică adoptată conștient de o grupare, oricare ar fi similaritatea sau diferența aparentă a producției lor”.1

În 2009, am răspuns invitației lansate de arhitecta franceză Odile Decq de a reinterpreta Manifestul Futurismului (Manifeste du Futurisme2), de F.T. Marinetti, publicat în jurnalul parizian Le Figaro cu un secol în urmă. Amintindu-mi că acest manifest cuprindea o serie de afirmații problematice, am răspuns într-un ton provocator, avansând idea că avangarda a murit! Nu am argumentat această declarație printr-o analiză istorică serioasă, ci printr-o ușoară formă de pamflet, pe care am numit-o „Futurism la Paris” (Futurisme à Paris3), reinterpretând unul câte unul punctele pronunțate în 1909: - „adorarea pericolului”, compromisă de dezvoltarea rapidă a companiilor de asigurări, care „au în vedere” toate aspectele vieții cotidiene; - „frumusețea vitezei”, cândva apreciată de futuriști, transformată într-un sistem de marketing cu nume răsunătoare ale ultimelor modele de autoturisme; - „omul la volan, care își aruncă săgeata spiritului în jurul lumii”, devine subiect al strategiilor turismului de masă; - „mulțimea excitată de muncă, de plăcere și de revoltă” este transformată cu fervoare în simulațiile computerizate de „Second Life”; - „curajul, îndrăzneala și rebeliunea” poeziei este absorbită de industria de publicitate, în timp ce poetul care „se investește cu ardoare, splendoare și generozitate” devine țărână etc. |

| Citiți textul integral în nr 5 / 2011 al Revistei Arhitectura. |

| 1Reyner Banham, „The New Brutalism”, The Architecture Review, London, December 1955, p. 3552Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, „Manifeste du Futurisme”, Le Figaro, Paris, 20th of February 1909.

3 Stefania Kenley, „Futurisme à Paris”, Spéciale Z, Déc. 2009. http://specialez.esa-paris.fr/?p=121 |

| At the beginning of the 20th century an Avant-Garde Movement had a clearly defined profile: a group of innovating artists with one or several spokesmen and with a provocative manifesto.Although highly controversial at the time, today the subject is part of a closed chapter of the modern art history, already analyzed, classified, and mostly agreed upon. In 1955, Reyner Banham distinguished two kinds of group profiles when writing “The New Brutalism” article in the Architectural Review: “One, like Cubism, is a label, a recognition tag, applied by critics and historians to a body of work which appears to have certain consistent principles running through it, whatever the relationship of the artists; the other, like Futurism, is a banner, a slogan, a policy consciously adopted by a group of artists, whatever the apparent similarity or dissimilarity of their products.”1In 2009, I responded to the invitation of the French architect Odile Decq for giving a new reading of the “Manifeste du Futurisme”2, by F.T. Marinetti published in the Parisian journal Le Figaro, a century earlier. Having in mind this Manifesto as a series of rather problematic declarations, I answered in a provocative tune, advancing the idea that the avant-garde is dead! I did not defend my statement via a serious historical analysis but through the light form of a pamphlet that I called “Futurisme à Paris”3, reinterpreting one by one the initial points spelled out in 1909:

- the “love of danger”, compromised by the rapid growth of insurance companies “taking care” of all aspects of the daily life; - the “beauty of speed” once prized by futurists, turned into a marketing system with resonant names for the latest car models; - the “man at the wheel, who hurls the lance of his spirit across the Earth”, become subject of tourism strategies; - the “crowds excited by work, by pleasure, and by riot”, transformed with fervour in “Second Life” computer simulations; - the “courage, audacity and rebellion” of poetry, absorbed by the advertising industry, while the poet who “spends himself with ardour, splendour, and generosity”, has turned to dust, etc. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |

| 1Reyner Banham, „The New Brutalism”, The Architecture Review, London, December 1955, p. 3552Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, „Manifeste du Futurisme”, Le Figaro, Paris, 20th of February 1909.

3 Stefania Kenley, „Futurisme à Paris”, Spéciale Z, Déc. 2009. http://specialez.esa-paris.fr/?p=121 |

i2 - Zaha Hadid Architects, MAXXI, vedere a holului spre biroul de informații și bilete, și spre vechea cazarmă Montello, transformată și integrată în spațiul muzeului / Zaha Hadid Architects, MAXXI - National Museum of XXI century arts, in Rome, Italy, 1998-2009, view of the hall towards the information and ticket counter and the former Montello barracks converted and integrated in the museum space

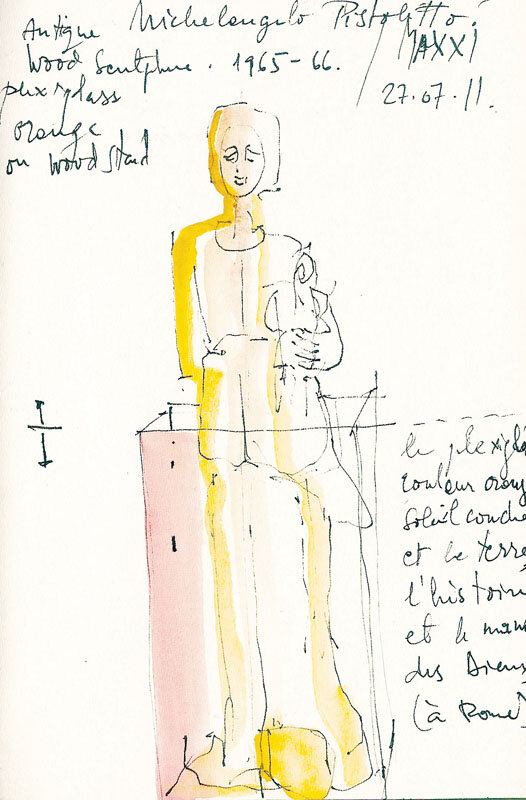

i3 - „Fotografierea interzisă!”, Stefania Kenley, desen în tuș și acuarelă pe hârtie, reprezentând o sculptură antică de lemn, plasată într-o cutie de plexiglas portocaliu pe suport de lemn și semnată de Michelangelo Pistoletto (1965-1966), expoziția retrospectivă „Da Uno a Molti, 1956-1974”, („De la unul la mulți”), MAXXI, 2011 / „No photographs please!”, Stefania Kenley, ink drawing and watercolour on notebook paper featuring an antique wood sculpture placed in orange plexiglass on woodstand, signed by Michelangelo Pistoletto (1965-1966), in the retrospective exhibition „Da Uno a Molti 1956-1974” at MAXXI, 2011