abruptarhitectura - case de oameni

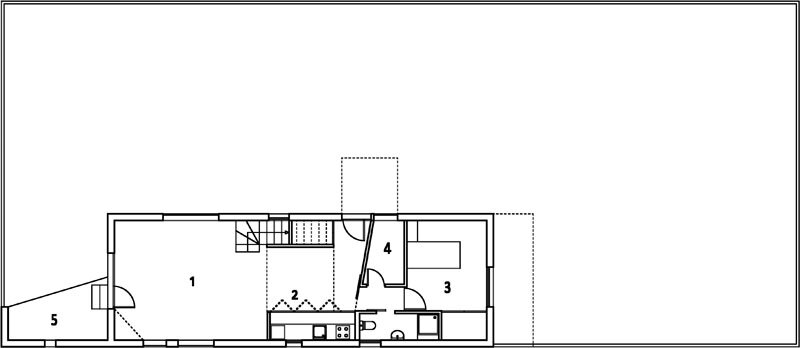

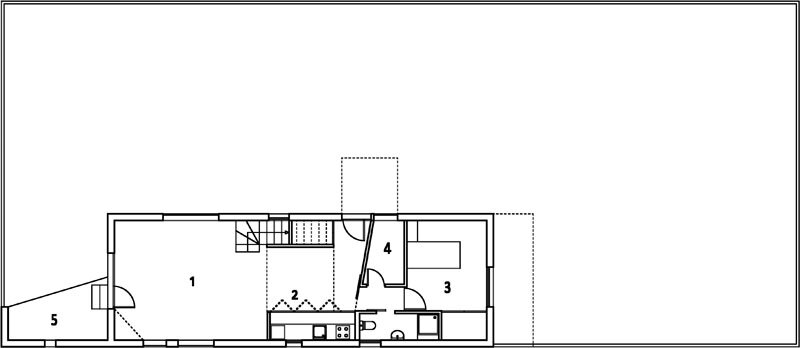

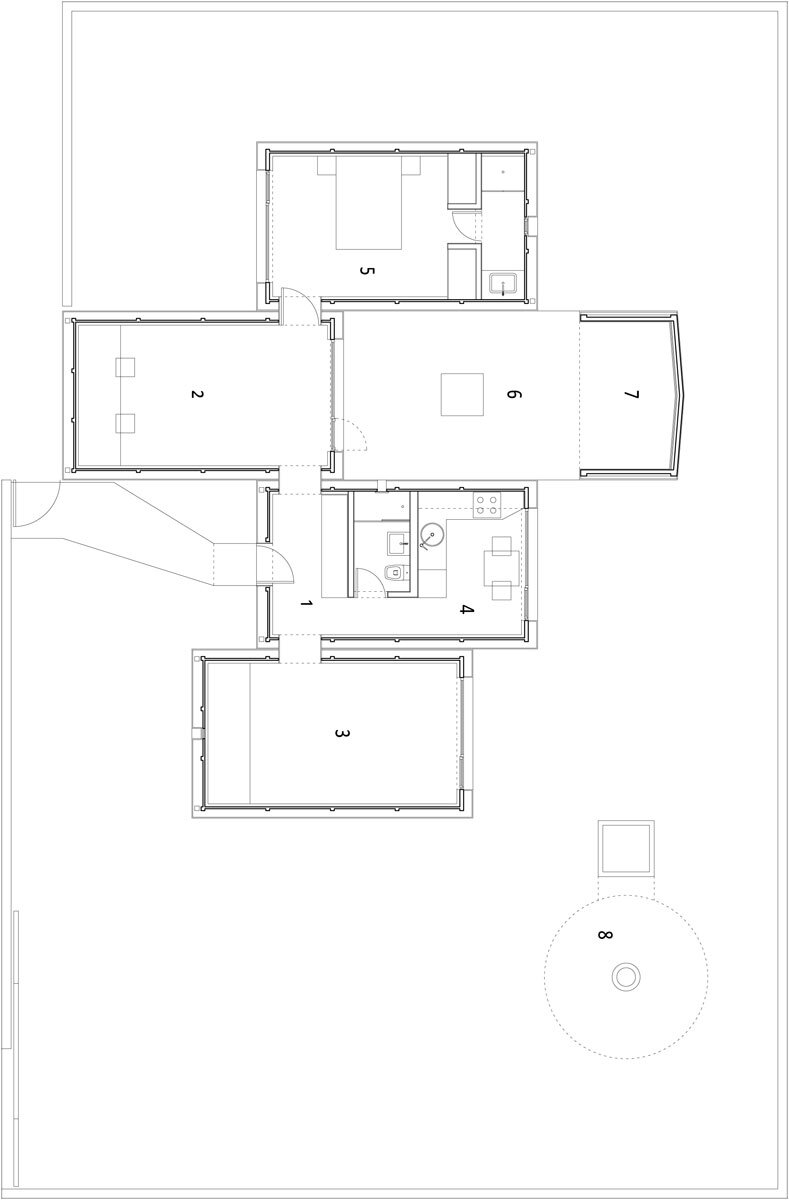

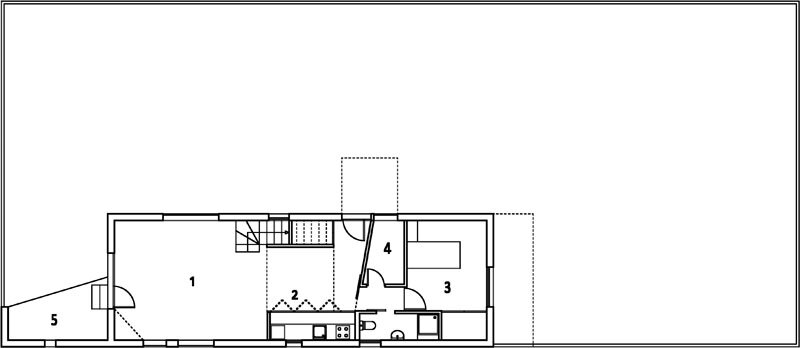

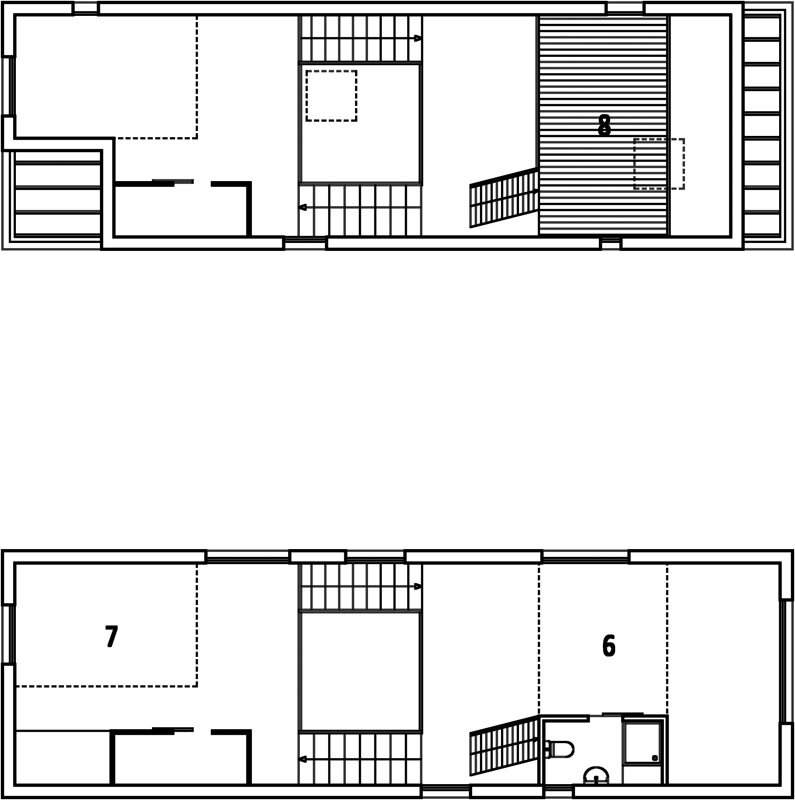

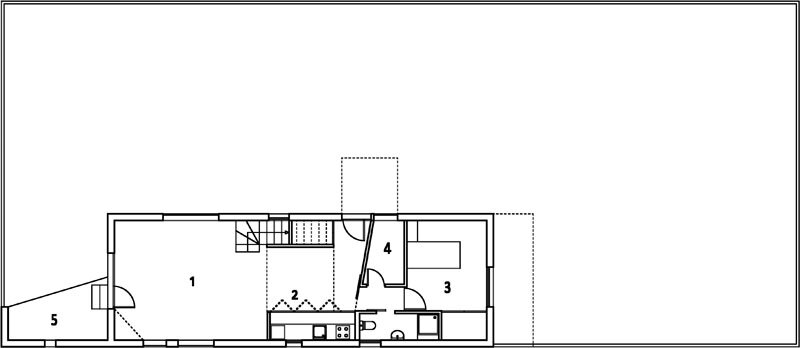

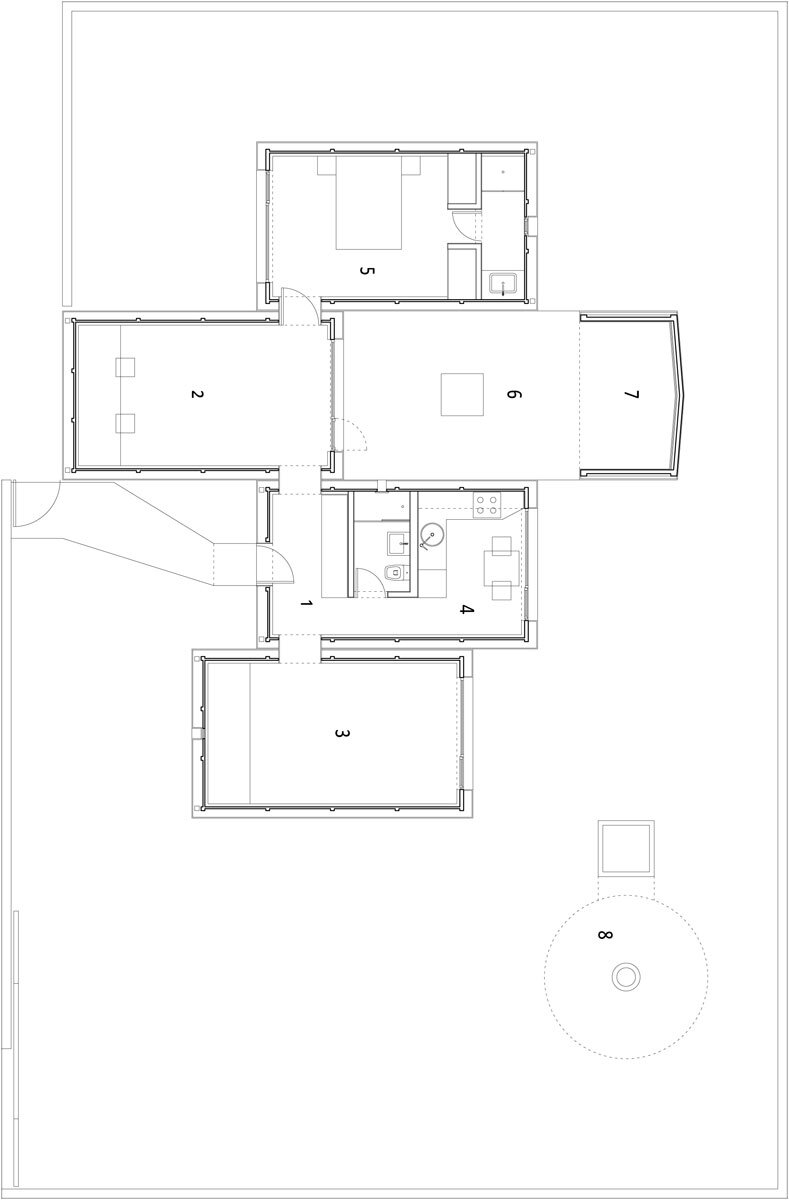

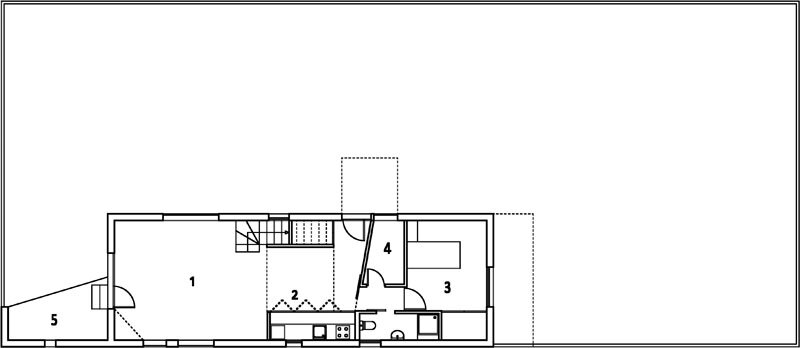

1. camera mare 2. bucătărie 3. camera de oaspeți 4. centrala termică 5. adăpost afară / 1. main room 2. kitchen 3. guest room 4. heating room 5. studio

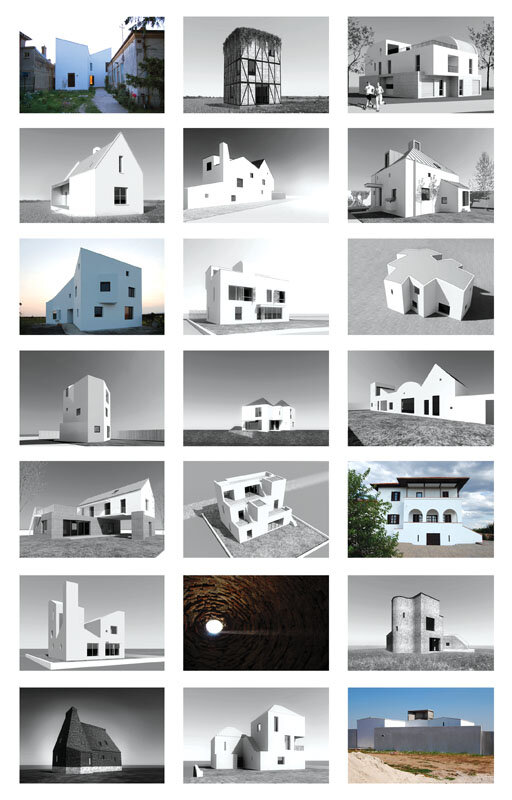

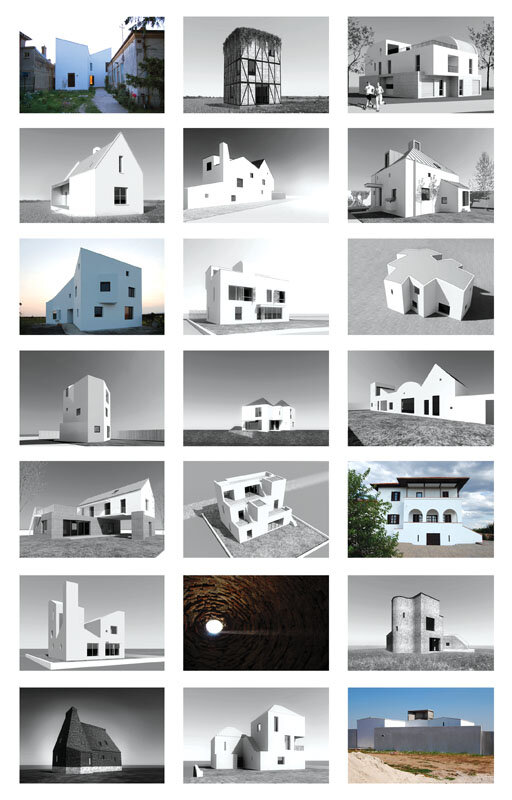

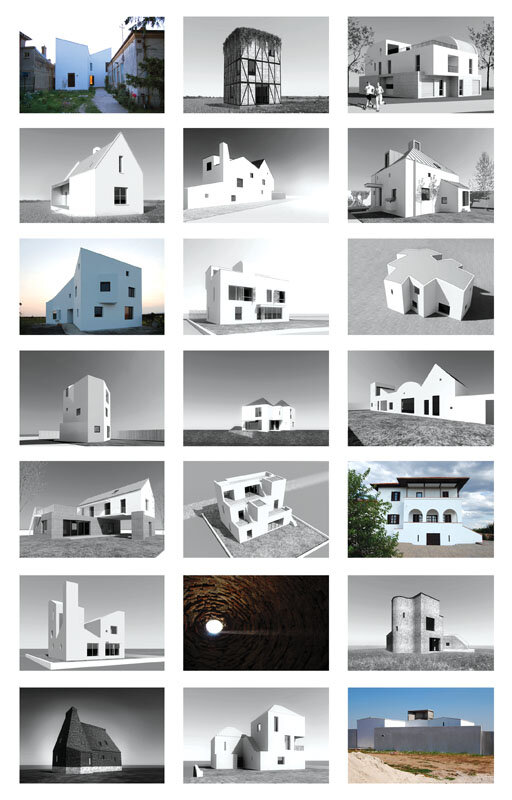

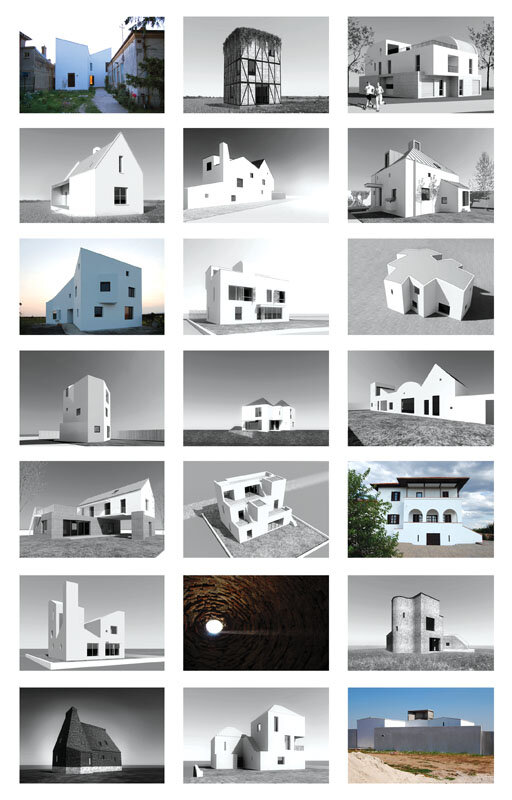

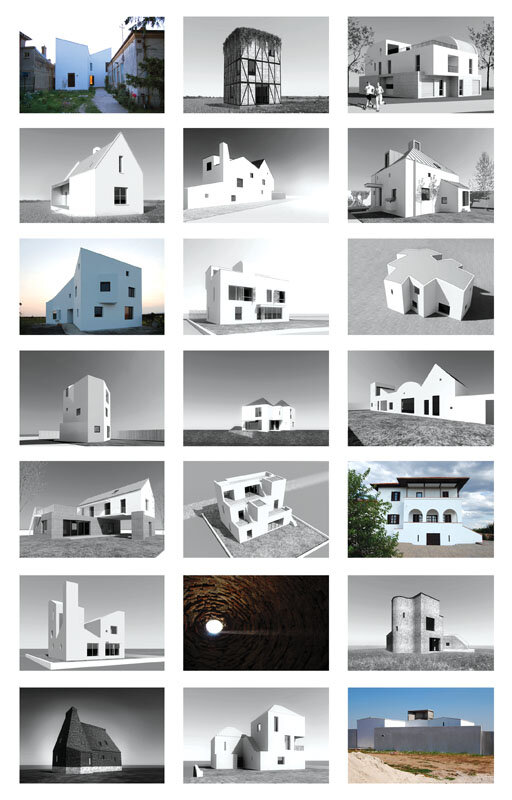

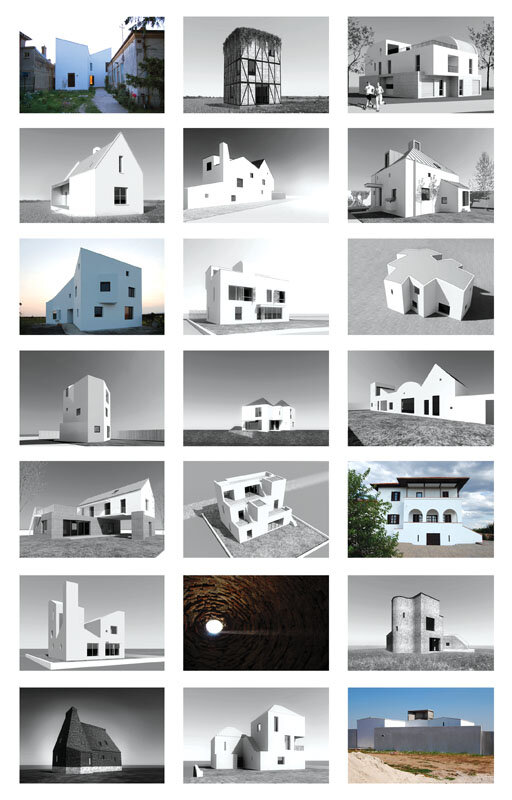

houses

| Casele noastre se vor case de oameni. Cu adevărat, am spune, ele n-ar mai fi ale noastre dacă ar fi pe deplin ale lor. Doar căutare în mers, despre asta se aduce vorba aici. Ce înseamnă să faci casa unui om? Este întrebarea căreia ne străduim să îi purtăm de grijă. Restul se adaugă în jur. Și tot ce înfășoară în juru-i această grijă devine uneori firea, adică felul în care casa îi ține pe ai săi laolaltă, în preajmă.Când ni s-a propus să facem acest material, ne‑am gândit că vom scrie o introducere în care să spunem Cum facem, și De ce facem așa cum facem, și Ce este o casă pentru noi, și altele asemenea. Am început și am văzut cât de bombastic ar putea suna și ne-am zis că e prea devreme, că de fapt nu știm, că e poate mai bine să zică alții. Ne-am amintit de un text care ne-a mișcat într-un fel anume, atunci când ne-a picat în mâini. Pentru noi a fost un fel de alinare a încrâncenării în arhitectura de mouse și ne-a reamintit că nu trebuie să știi mare lucru pentru a locui sau a face o casă. Iată textul lui G. M. Cantacuzino, rostit la radio în ’37, „Locuința românească”:

„Sunt case în care noi am stat zile multe și care totuși rămân în amintirile noastre străine și reci, neprielnice evocării vreunei stări sufletești, decoruri la care privind parcă altcineva ar fi trăit în ele. Altele, dimpotrivă, sunt în memoria noastră oaze calde în care ne regăsim, în care se continuă ceva din noi, în care ne întoarcem cu gândul pentru a privi în oglinzile pline de umbră adâncimea timpului trecut. Sunt case sub al căror acoperiș am stat de-abia o zi, ori numai o noapte, călători grăbiți ce suntem mereu. Totuși ele sunt pe harta drumurilor noastre lăuntrice ca popasuri fericite de unde am plecat mai voioși înainte. Și sunt case în care unii din noi trăiesc de ani și ani de zile în cenușiul monotonei datorii, pe care nici nu le văd, nici n-ar putea să le descrie. Când fac o casă pentru cineva, un cineva anonim, de care nu știu prea mult, pe care-l ghicesc puțin cât îmi trebuie pentru a-i înțelege dorințele, mă gândesc întotdeauna la acea înrâurire a caselor, a camerelor, a spațiilor locuite, cu propria lor sonoritate, cu deosebita lor lumină, asupra acestor amintiri, acestui trecut mereu mărit și în veșnică transformare din care ni se compune personalitatea.Încerc să înțeleg de ce anumite ferestre se deschid și astăzi pentru mine pe priveliștile surâzătoare ale țărilor făgăduinței, de ce unele camere la anumite ore aveau ceva solemn în creșterea întunerecului care le cuprindea, de ce unele scări puneau hotare între caturi în loc ca să le lege, de ce unele uși prea mari înspăimântă de parcă ele ar trebui să se deschidă numai pentru un alai, de ce unele case sunt locuite de sufletul vremurilor, pe când de altele niciodată nu se prinde viața? Îmi pun toate aceste întrebări și totuși nu răspund, nu pot răspunde la fiecare în parte, dar din suma lor încerc să-mi fac o intuiție care va fi cheia cu care voi nădăjdui a pătrunde în lumea a ceea ce numim noi, cu totul fără socoteală, a obiectelor neînsuflețite. Căci nimic nu este mai viu - sau nu ar trebui să fie mai viu - decât o casă. Dar cine dă casei acest suflet inițial? Cei cari o locuiesc? Nu. Atunci? E treaba ta, tu care ești arhitect, să dai fațadelor priviri și încăperilor sonoritatea vieții. Numai cu această condiție arhitectul este un creator… de nu, el rămâne un simplu făcător de decoruri tot atât de artificiale ca acelea de pe scena unui teatru. A face decoruri se poate învăța. Sunt reguli, calapoade, ba chiar rețete pentru acest soi de meserie. A da viață însă unei case, fie ea cât de simplă, nu se învață. E un dar pe care-l ai sau nu, cu care te naști… un har care nu se găsește nici la școală, nici în biblioteci, e un soi de simț al spațiilor și al destinului care se pătrund, dând naștere acestui joc de forme care se cheamă «arhitectură». Fac casa unui om… deci hotărnicesc un spațiu, o perioadă de timp care se cheamă viața acestui om. Creez o intimitate, dau premisele unui ritual al vieții zilnice. Voi colora, după felul cum va cădea lumina în casa pe care o voi zidi, amintirile, ba chiar speranțele, năzuințele celui care va trăi cu ai săi în spațiile dispuse de mine. Fac casa unui om… asta nu înseamnă numai că îl apăr de intemperii și că îi pun la dispoziție ceea ce se cheamă „confort”. Trebuie să îi mai dau posibilitatea de a uita că eu am fost vreodată părtaș la facerea casei lui, trebuie să îi dau toate șansele de asimilare a operei mele… căci numai atuncea dânsa va fi valabilă. Căci va veni ziua când fiul acestui om va spune: …casa tatălui meu, și în mintea copilului această casă va fi într-adevăr înfăptuirea tatălui său, și nicidecum a cutărui sau cutărui arhitect… și numai așa va fi bine și va fi drept. Fac casa unui om… dau deci o înfățișare năzuințelor sale. Fac un soi de portret abstract, mărturisesc pentru dânsul ceea ce poate că nici dânsul nu știa că avea de mărturisit, îl pun în fața dorințelor sale, le exprim pe cât se poate, îl pun în fața maniilor sale… le combat pe cât se poate. Și din rezistența mea și din voința lui se face o casă. E un soi de colaborare între doi străini, un joc magic al intuiției. Fac casa unui om… las deci orașului în care el trăiește întipărirea voinței sale. În conglomeratul social al unui oraș, schițez ideograma unei personalități. Casa terminată, ea va deveni cu totul a lui. Va fi casa cutărui, prin fața căreia și eu voi trece odată, uitând aproape că am făcut-o. Și când casa va fi gata, când ultimul tâmplar, ultimul electrician ori zugrav va fi ieșit dintr-însa, mă voi retrage și eu pe vârful picioarelor, ca să nu se auză că am plecat și totodată să se uite că am fost...” * |

| * G. M. Cantacuzino, Izvoare și popasuri, Editura Eminescu, București, 1977 |

| Our houses aim to be houses for people. Indeed, we might say, they wouldn’t be ours if they were so truly theirs. It is only a quest along the road; this is what is being discussed here. But what does it mean to make a man’s house? It is the question we strive to answer. The rest wraps around it by itself, and becomes sometimes its nature, the manner in which the house keeps all its inhabitants together, around it.When we were proposed to write this article, we thought about writing an introduction in which to say How we do it and Why we do it that way, What a house means to usand such. So we set about doing that and realized how emphatic it might sound and thought that maybe it was too early, that maybe we didn’t know, that maybe it was better if others spoke about it. We recalled a text which had particularly moved us when we had come across it. It deeply comforted us during our grim pursuit of “mouse architecture” and reminded us that you needn’t know a lot to inhabit or to make a house. It is a text delivered by G. M. Cantacuzino on the radio in 1937, entitled “The Romanian Dwelling”:

“There are houses in which we spent many days and which, nevertheless, left a cold, hostile trace on our memories, unable to evoke any state of mind, settings that, when looked back at, seem to have been inhabited by someone else. There are others, on the contrary, which find their place in our memory like warm oases, in which we find ourselves, where something from inside us is continued, houses that we revisit in order to look, in their shade-filled mirrors, for the depth of the time past. These are houses under whose roof we barely spent a day or a night, like the hurried travelers that we always are. And still they remain on the map of our inner roads like happy shelters whence we moved on more cheerful. And there are also houses in which people have been living for years on end, overwhelmed by grey monotonous duties, and which they are neither able to see clearly, nor to describe. When I make a house for someone, an anonymous someone about whom I do not know much and I tend to make guesses in order to understand his or her wishes, I always think about the authority of houses, rooms, inhabited spaces possessing their own sonority, their own light, about these memories, this past, constantly augmented and undergoing eternal transformation, which forms our personality.I am trying to understand why certain windows are still opening today, for me, onto the sunny views of the promised land, why some rooms at certain hours acquired something solemn as it grew darker and darker, why some stairs put up borders between storeys instead of connecting them, why some doors that were too big frightened me as if they had to open only for a procession, why some houses are inhabited by the spirit of their times while others never seem to latch on to life? I ask myself all these questions and still I cannot answer them; I cannot answer each of them in turn, but from them all I try to form an intuition which will be the key that will help me penetrate the world of inanimate objects, as so inconsiderately we call it. Inconsiderately because there is nothing livelier - or there shouldn’t be anything livelier - than a house. But what animated this house, originally? The people who live in it? No. But what, then? It is your job, yours, the architect, to imbue the façades and the rooms with the look and sonority of life. It is only by meeting this requirement that the architect becomes a creator. Otherwise, he stays a mere builder of settings, just as artificial as the theater ones. One can learn how to make settings. There are rules, molds, even recipes for this kind of craft. But to give life to a house, however simple, cannot be learnt. It is a gift that you either have or you don’t, that you are born with… a gift not to be acquired in school or in libraries, a special mixed sense of space and destiny which gives rise to the play of forms referred to as ‘architecture’. I make a man’s house… therefore I trace the boundaries of a space, of a period of time which is that man’s life. I create intimacy; I furnish the premises for a ritual of daily life. I shall color, according to the way light falls on the house about to be built, the memories, even the hopes, the aspirations of that person who will live together with his family in the spaces arranged by me. I make a man’s house… this does not mean solely that I protect him from bad weather and I provide him with what is known as ‘comfort’. I need to give him the opportunity to forget that I have ever been involved in the making of his house, to give him all the chances he needs to appropriate my work… because it is only then that my work will be valid. Because that day will come when that man’s son will say: …my father’s house, and in the child’s mind that house will truly be his father’s creation, and not that of some architect… and this is the only way and the right way to think about it. I make a man’s house… therefore I give shape to his aspirations. I make some sort of abstract portrait, I confess for him what he probably didn’t even know that he wanted to confess, I place him face to face with his manias, I express them to the fullest extent possible. And thus, my strength and his will combine in making a house. It is a collaboration between two strangers, a magic game of intuition. I make a man’s house… therefore I leave the imprint of his will on the city in which he lives. In the social conglomerate of a city, I trace the ideogram of a personality. Once completed, the house will become entirely his. It will be the house of that man, by which I shall also pass some day, almost forgetting that I made it. And when the house is finished, when the last carpenter, the last electrician or house painter has left it, I shall also withdraw on tiptoe, so that people stay unaware that I left and also forget that I was there.”* |

| * G. M. Cantacuzino, Izvoare și popasuri, Editura Eminescu, București, 1977 |

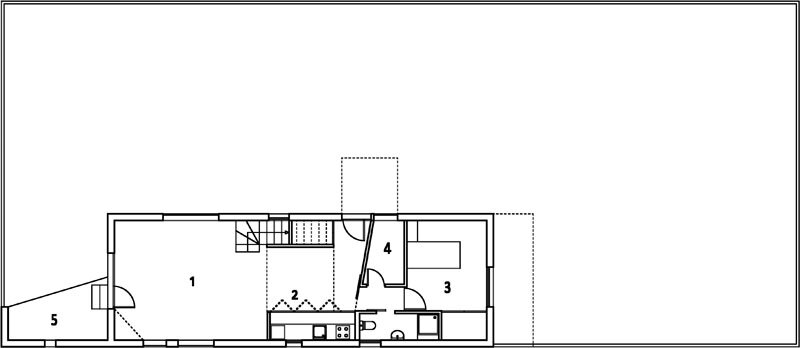

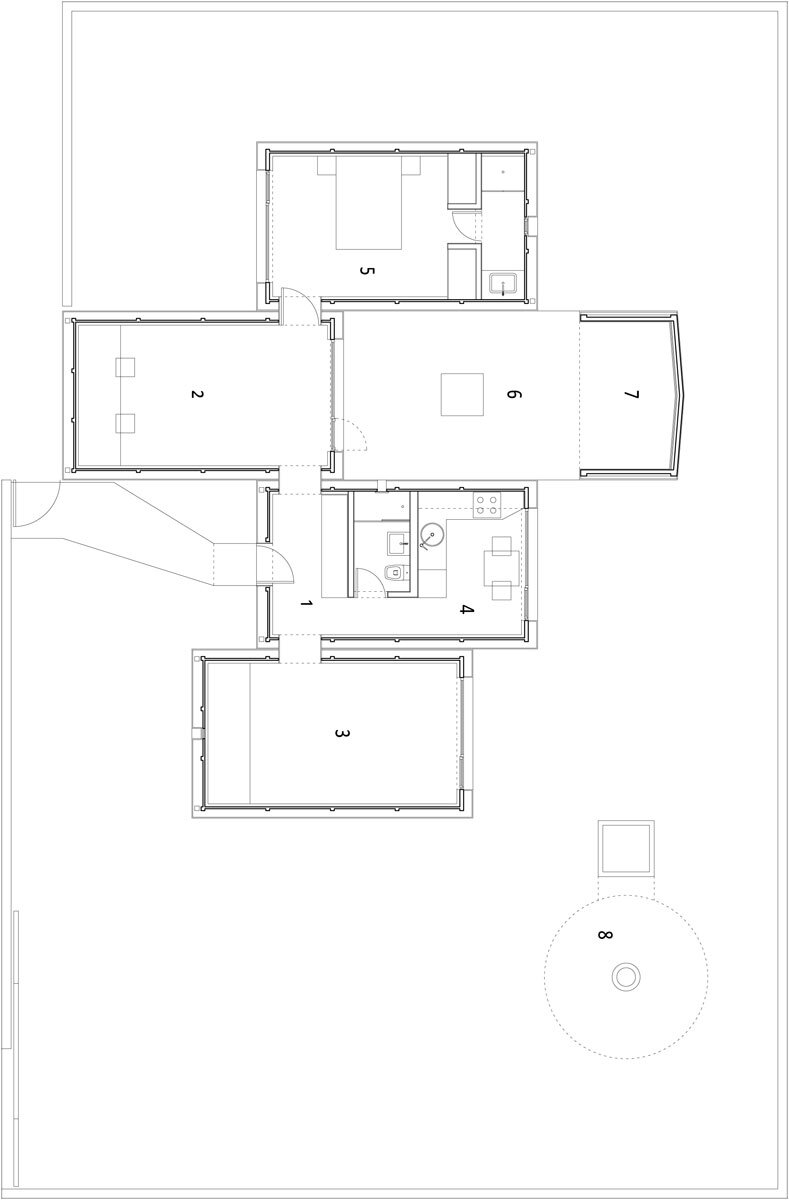

1. camera mare 2. bucătărie 3. camera de oaspeți 4. centrala termică 5. adăpost afară / 1. main room 2. kitchen 3. guest room 4. heating room 5. studio

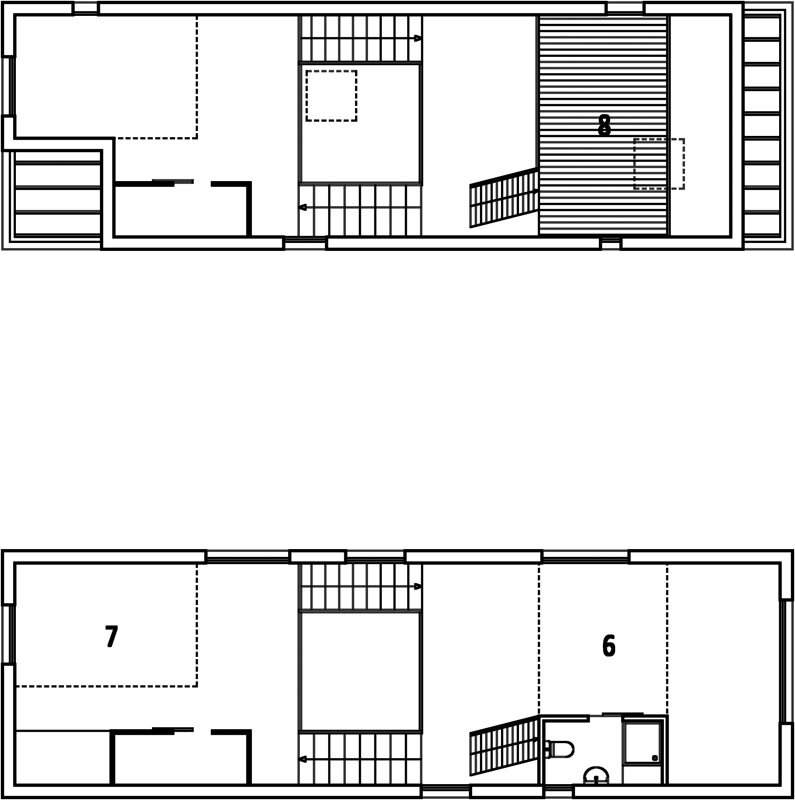

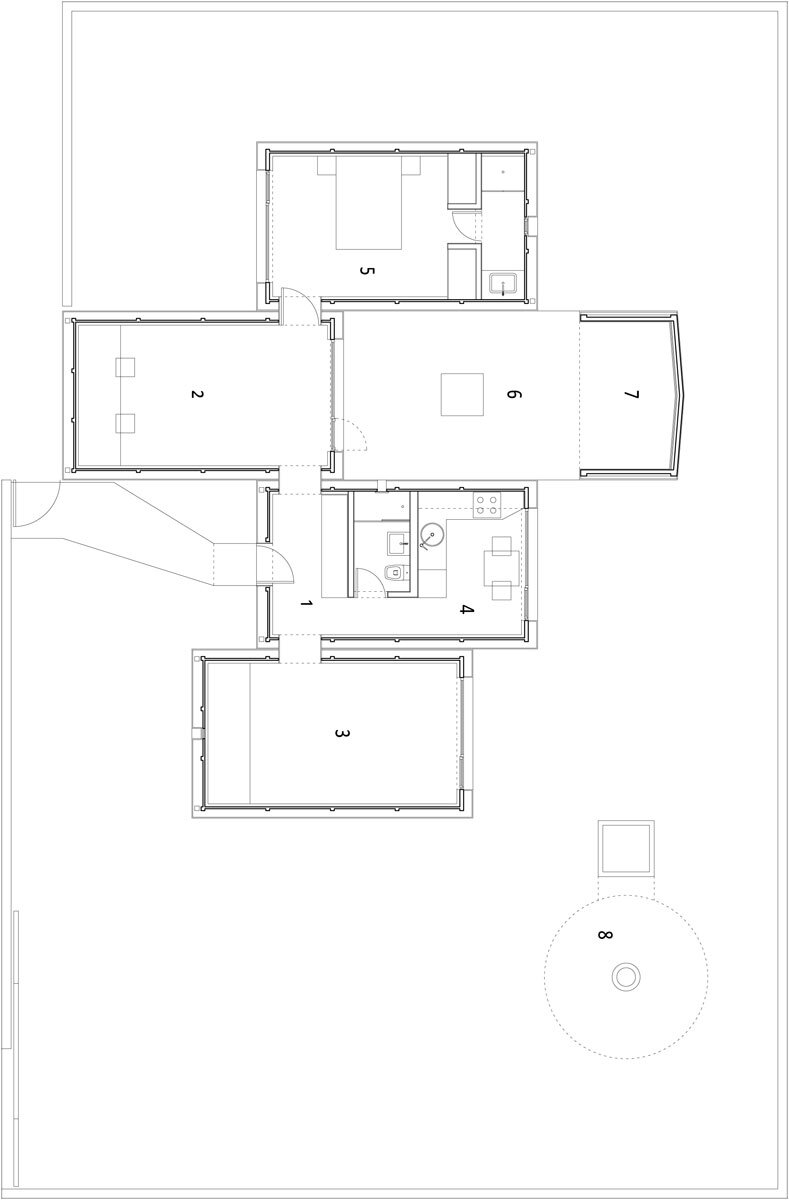

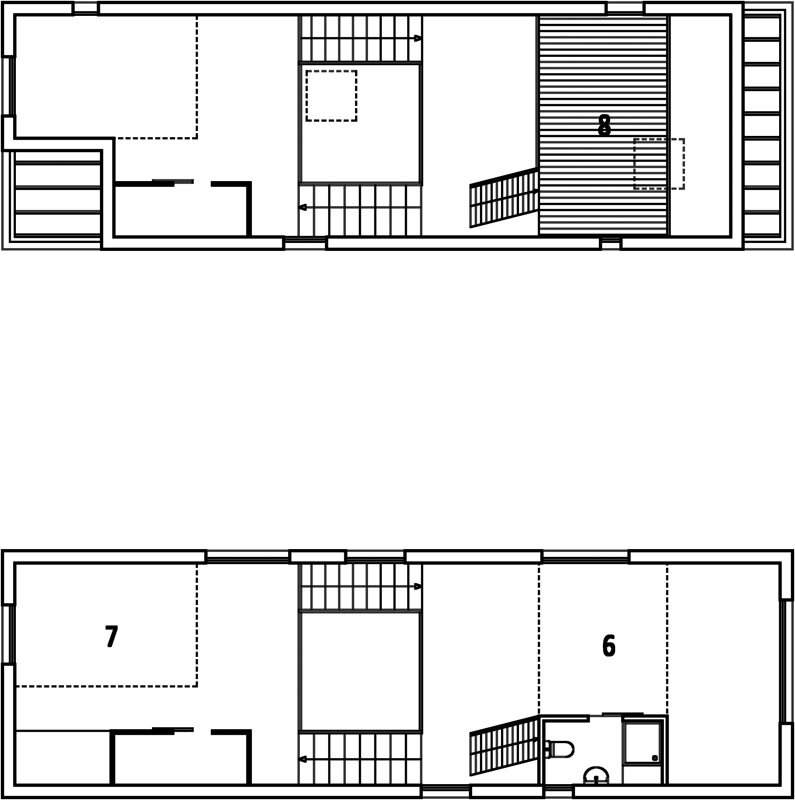

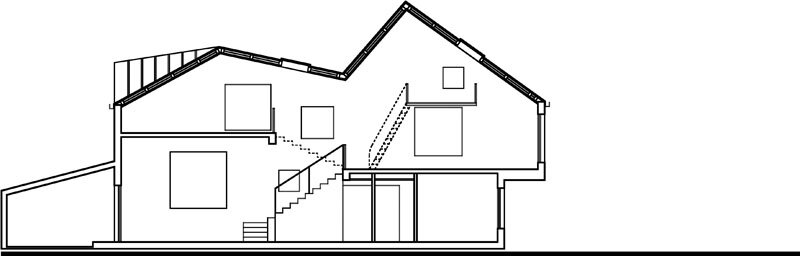

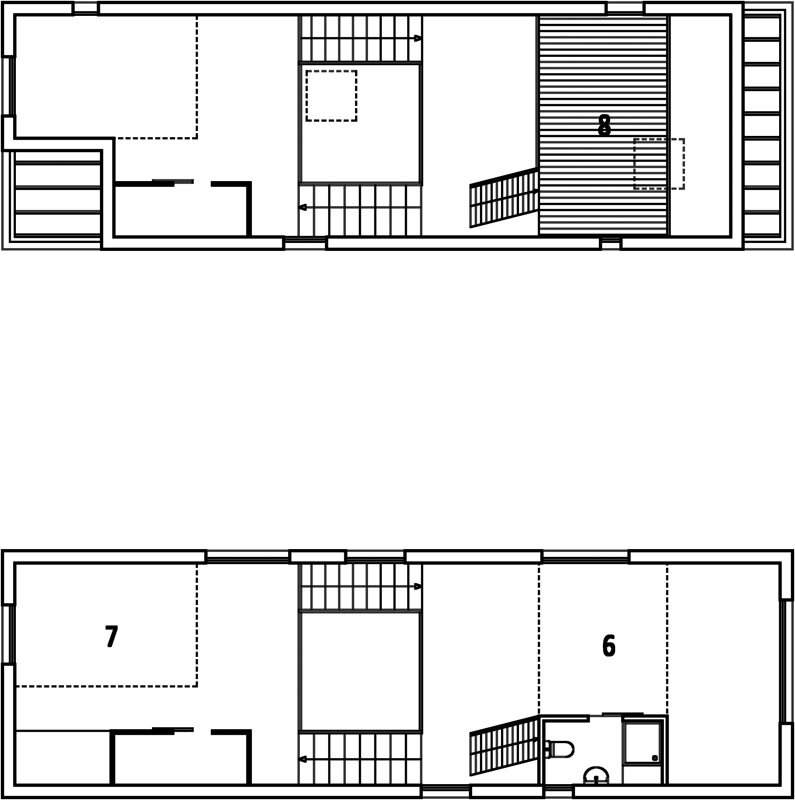

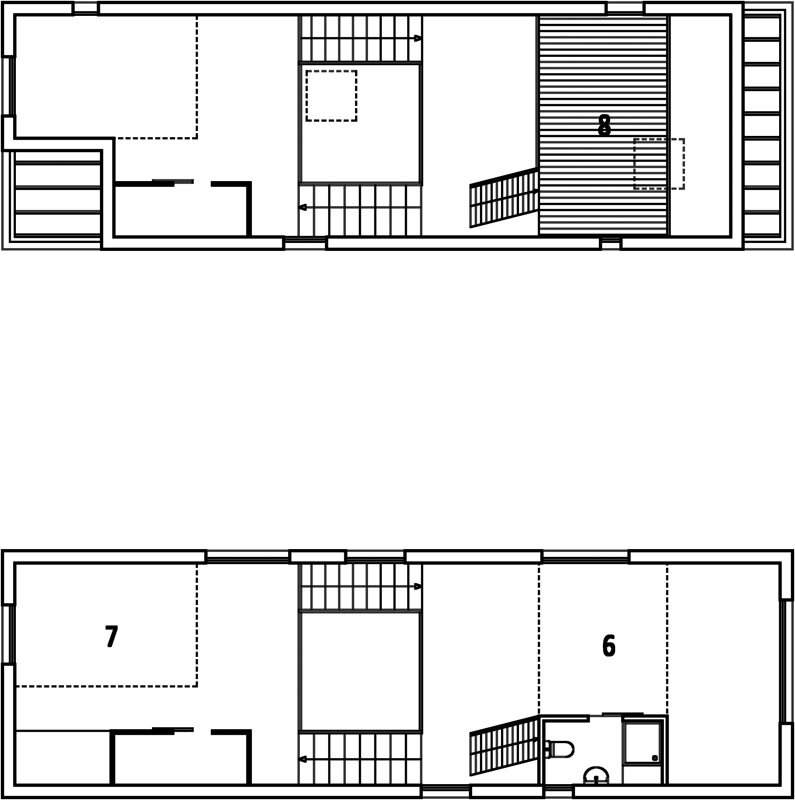

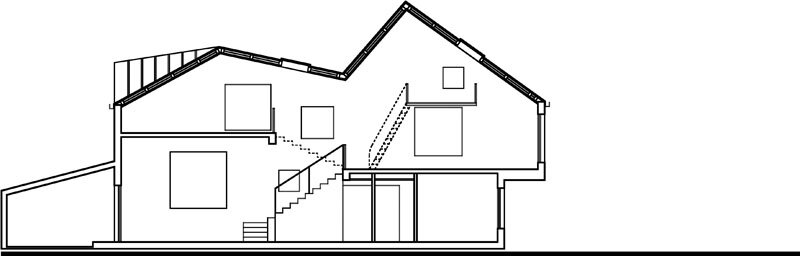

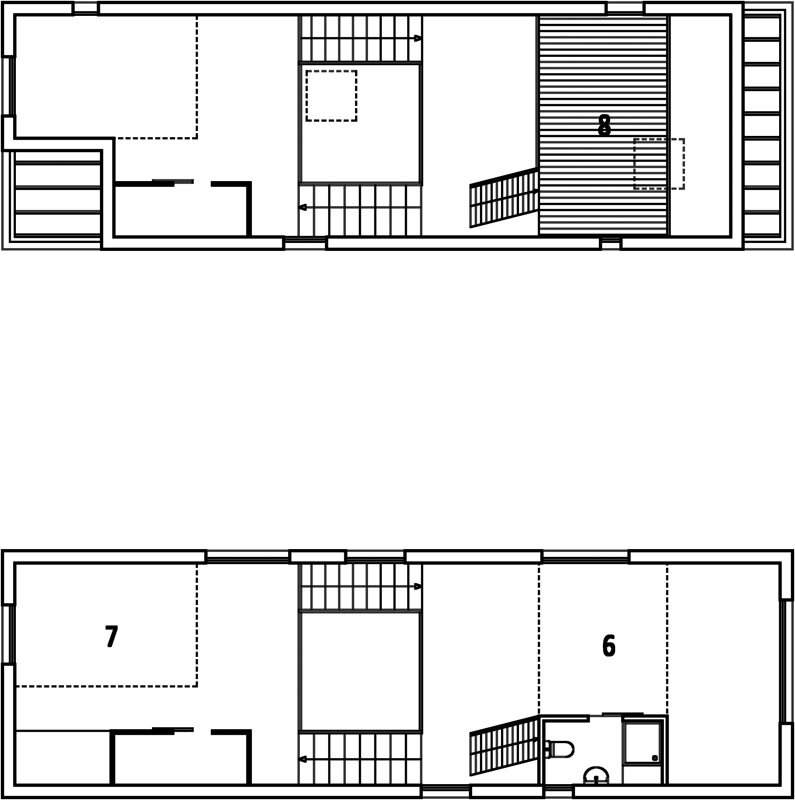

6. atelier 7. loc pentru somn 8. cu ochii la stele / 6. work room 7. bedroom 8. room towards the sky

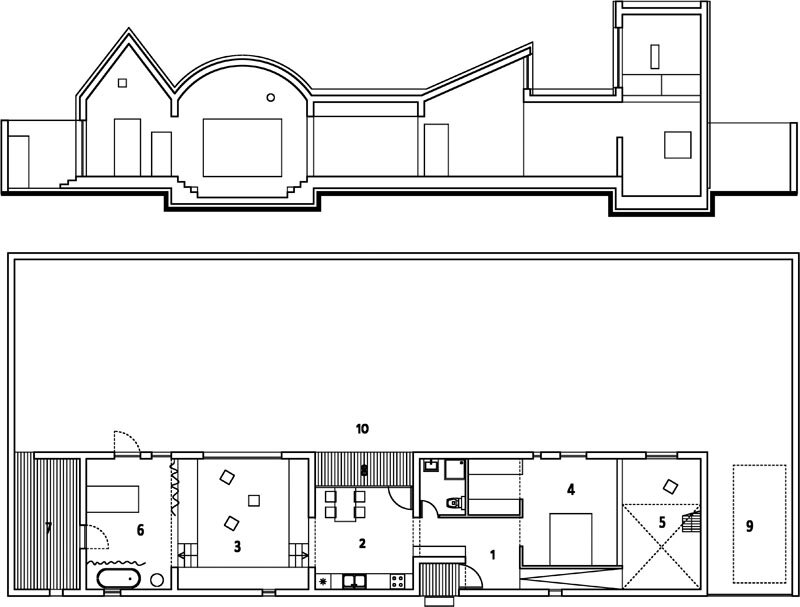

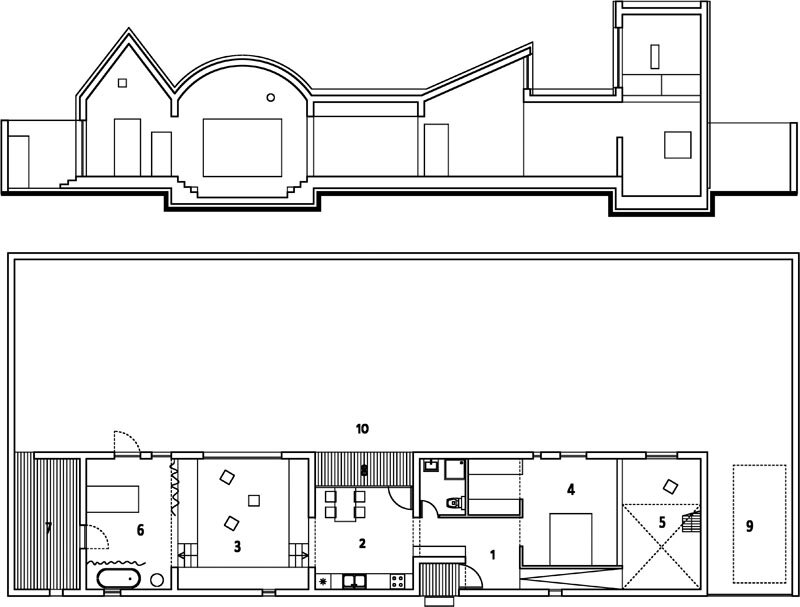

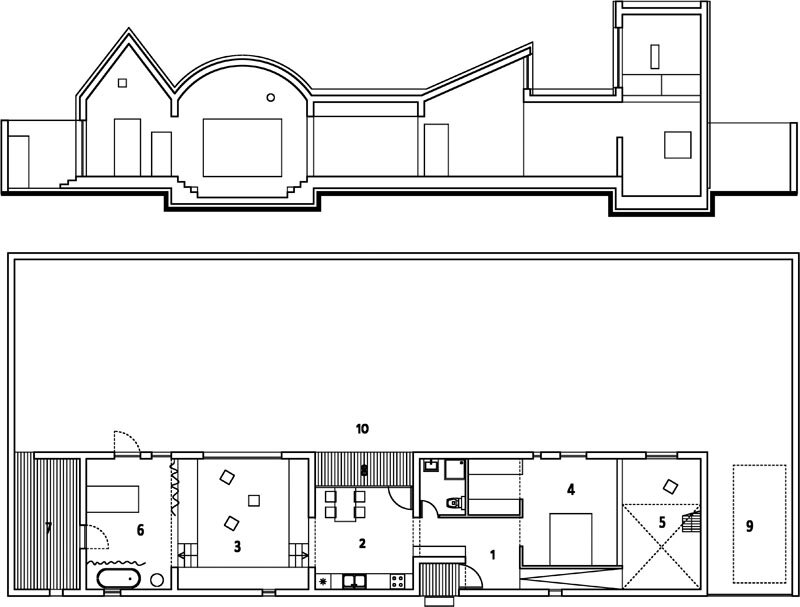

1. intrare 2. loc de luat masa 3. camera de zi 4. dormitor și dressing 5. atelier 6. camera de seară 7. grădină 8. terasă 9. loc pentru mașină 10. curte / 1. entrance 2. dining 3. living room 4. bedroom & dressing 5. studio 6. evening room 7. garden 8. terrace 9. parking space 10. courtyard

1. prispa 2. camera de zi 3. sufragerie 4. bucătărie 5. baie 6. dormitor 7. loc de joacă 8. camera copiilor / 1. porch 2. main room 3. dining room 4. kitchen 5. bath room 6. bedroom 7. playroom 8. kids’ room

1. casă la Cornetu 2. garaj 3. magazie / 1. house in Cornetu 2. garage 3. storage

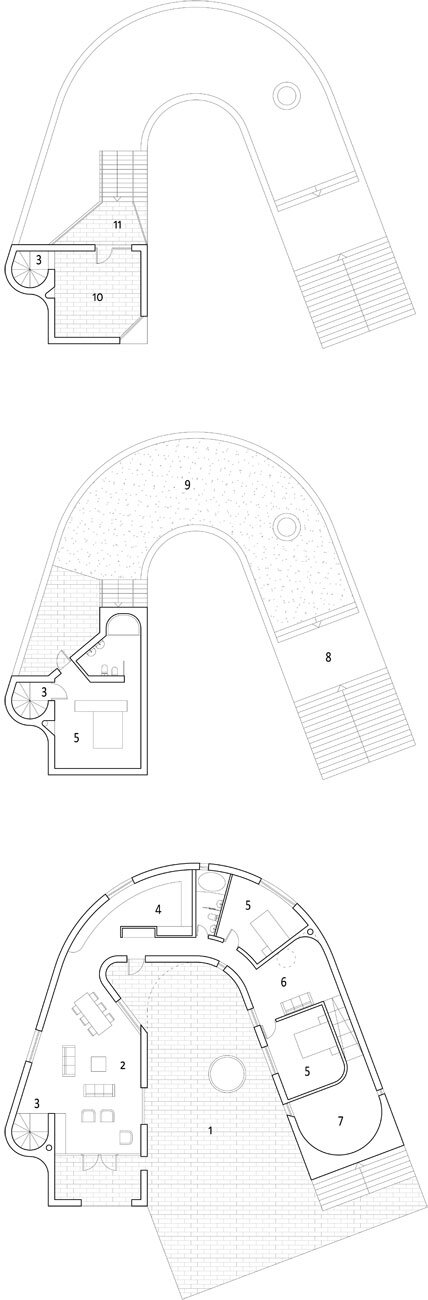

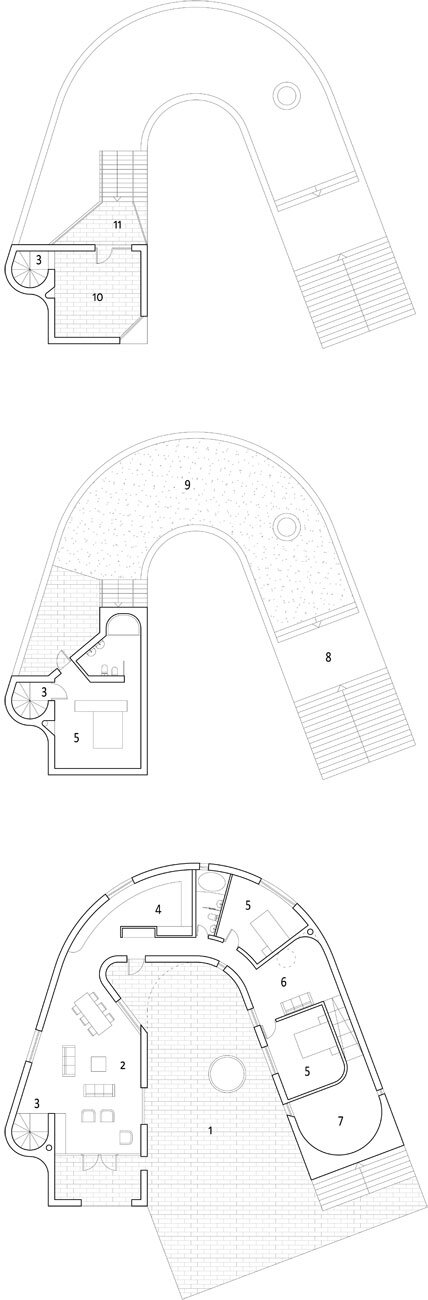

1. curte interioară 2. camera de zi 3. scară melc 4. bucătarie 5. dormitor 6. loc de citit 7. loc răcoros 8. terasă pietruită 9. terasă plantată 10. camera din turn 11. balcon / 1. courtyard 2. living room 3. spiral stairs 4. kitchen 5. bedroom 6. reading place 7. cool place 8. paved terrace 9. green terrace 10. tower room 11. balcony

1. intrare 2. lucru 3. cameră 4. bucătărie 5. somn 6. curte interioară 7. umbrar 8. tainiță / 1. entrance 2. workroom 3. room 4. kitchen 5. bedroom 6. patio 7. shelter 8. cellar

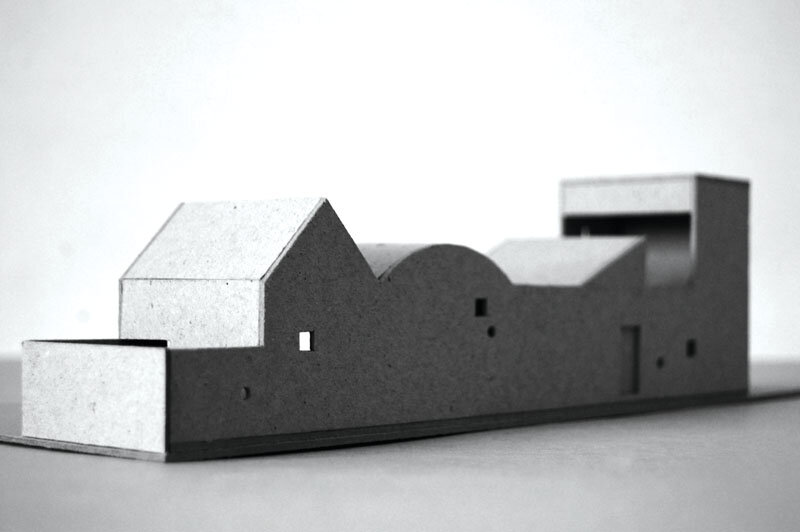

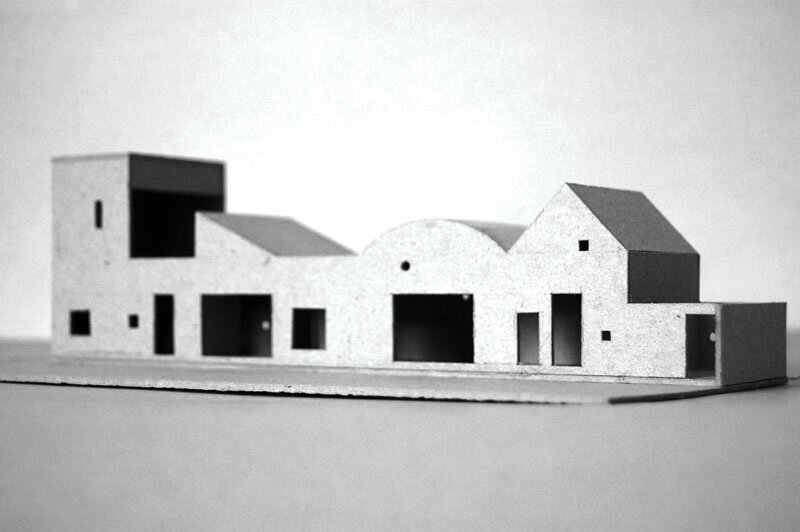

| UNA DIN CINCI CASE LA GULIA |

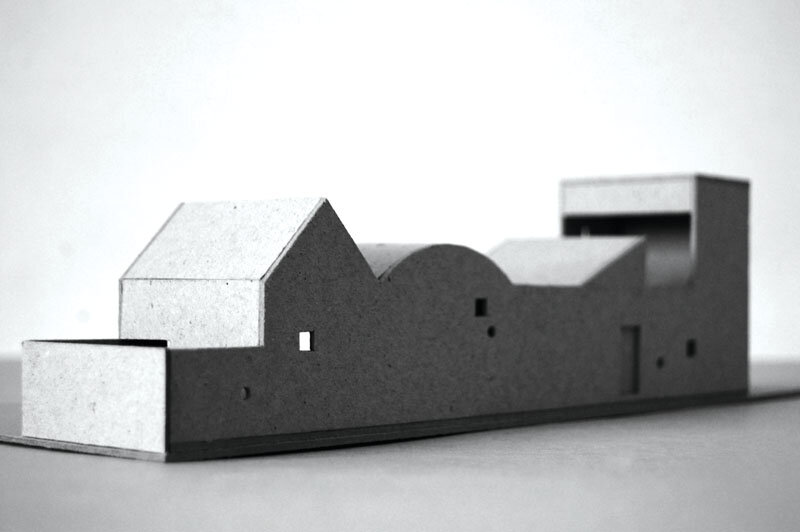

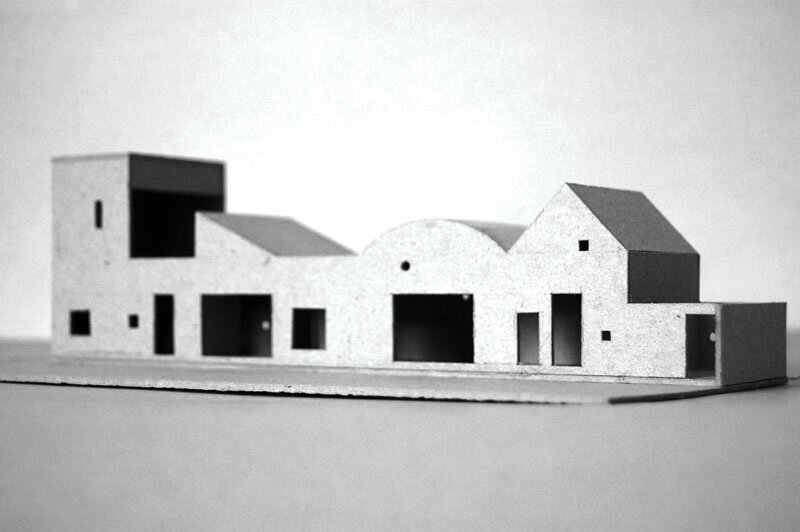

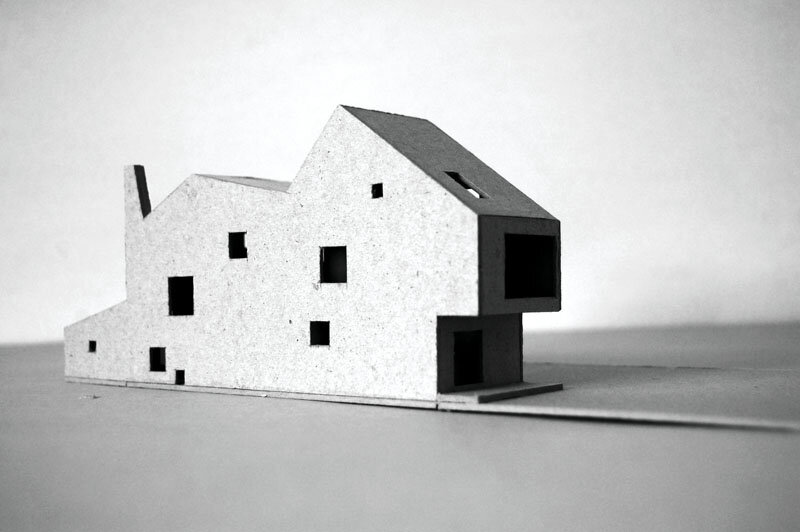

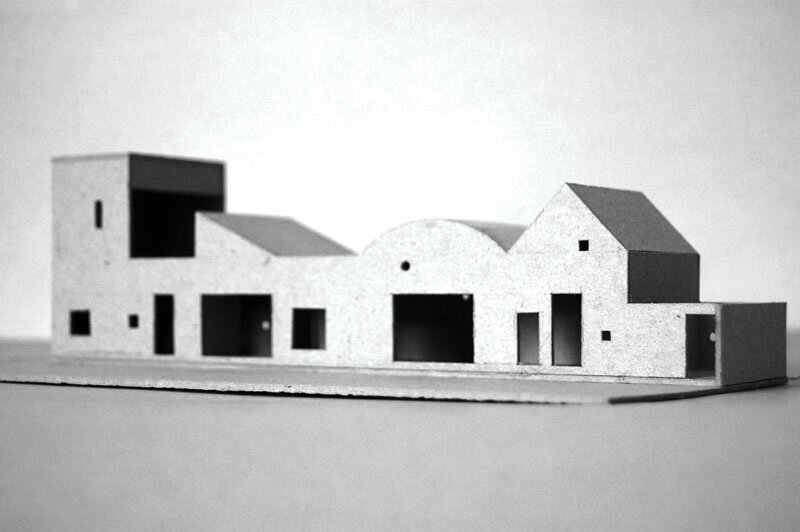

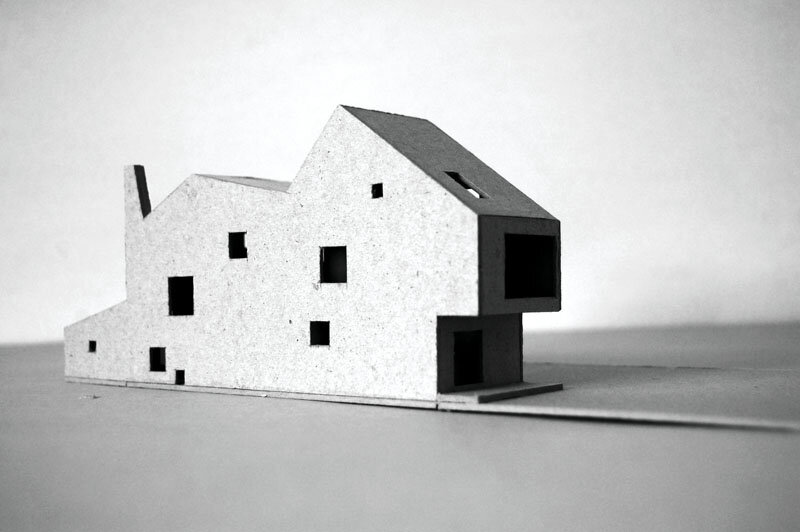

| Enona este un soi de „crăiasă strange”. Înaltă, cu un păr roșu foate lung, prietenoasă, se implică în acțiuni umanitare și își pictează singură fustele. Enona ar fi vrut o casă pentru ea. Doar în principiu pentru ea, căci poate ar fi venit aici și mama de la Brașov, sau poate ar fi devenit cândva casa unei Enone familiste. Totuși, acum, Enona ar fi vrut o casă cu locuri multe și nedeslușite: pentru dormit, stat cu prietenii, cusut, desenat sau pentru oaspeți. Pentru generozitatea temei a venit generozitatea ofertei. La a doua întâlnire, Enona ne-a găsit cu trei case pe care le-a numit politicos „căluțul”, „omida” și „miriapodul”. Dintre acestea, „căluțul” a fost cel mai îndrăgit, dar mai era de gândit. La a treia întâlnire, „căluțul” a mai crescut, dar i s-au adăugat două case compacte: „bastionul” și „turnul”. În cele din urmă, Enona a avut un vis. Se făcea că trebuie să aleagă între „căluț” și „turn”. Din păcate, ițele locului s-au încurcat și acum se așteaptă pentru o vreme. |

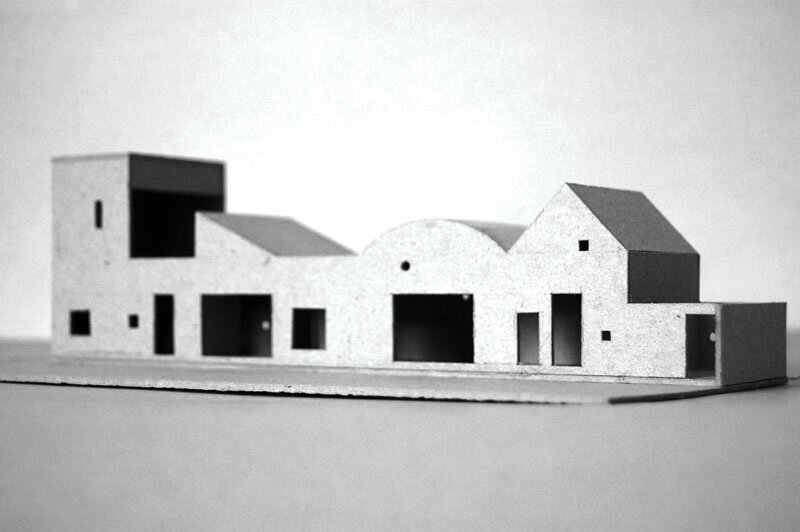

| ONE OF FIVE HOUSES AT GULIA |

| Enona is a kind of “strange princess”. Tall, with red, very long hair, friendly, she gets involved in humanitarian actions and paints her own skirts. Enona would have wanted a house just for herself. In principle, that is, because her mother from Brașov could have joined her there or maybe it could have become, some day, the house of Enona’s family. Still, at this point in time, Enona would have liked a house with numerous and vague places to be: for sleeping, for chatting with friends, for sewing, drawing or for guests. The generosity of the theme was met by the generosity of the offer. On the second meeting, Enona found us with three houses which she politely called “the little horse”, “the caterpillar” and “the myriapod”. Of these, “the little horse” was the most loved, but there was still some thinking to be done about it. On our third meeting, “the little horse” had grown some more and had been adjoined by two compact houses: “the stronghold” and “the tower”. Finally, Enona had a dream. In that dream, she had to choose between the “little horse” and “the tower”. Unfortunately, things became complicated on site and now everybody has decided to sit and wait for a while. |

1. camera mare 2. bucătărie 3. camera de oaspeți 4. centrala termică 5. adăpost afară / 1. main room 2. kitchen 3. guest room 4. heating room 5. studio

6. atelier 7. loc pentru somn 8. cu ochii la stele / 6. work room 7. bedroom 8. room towards the sky

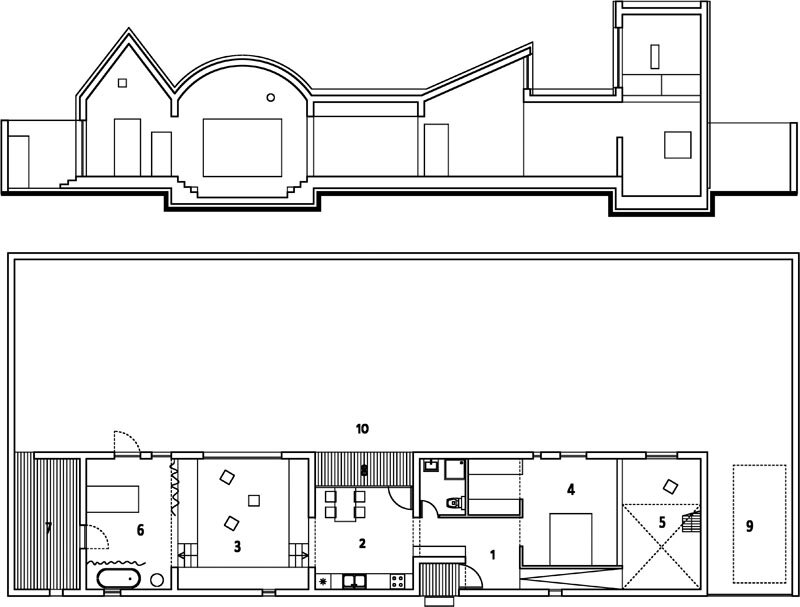

1. intrare 2. loc de luat masa 3. camera de zi 4. dormitor și dressing 5. atelier 6. camera de seară 7. grădină 8. terasă 9. loc pentru mașină 10. curte / 1. entrance 2. dining 3. living room 4. bedroom & dressing 5. studio 6. evening room 7. garden 8. terrace 9. parking space 10. courtyard

1. prispa 2. camera de zi 3. sufragerie 4. bucătărie 5. baie 6. dormitor 7. loc de joacă 8. camera copiilor / 1. porch 2. main room 3. dining room 4. kitchen 5. bath room 6. bedroom 7. playroom 8. kids’ room

1. casă la Cornetu 2. garaj 3. magazie / 1. house in Cornetu 2. garage 3. storage

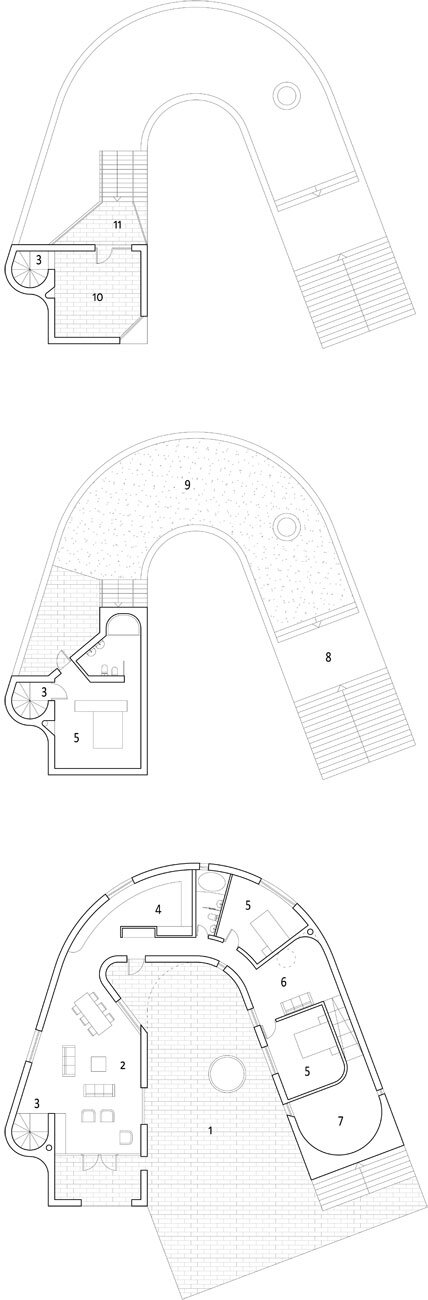

1. curte interioară 2. camera de zi 3. scară melc 4. bucătarie 5. dormitor 6. loc de citit 7. loc răcoros 8. terasă pietruită 9. terasă plantată 10. camera din turn 11. balcon / 1. courtyard 2. living room 3. spiral stairs 4. kitchen 5. bedroom 6. reading place 7. cool place 8. paved terrace 9. green terrace 10. tower room 11. balcony

1. intrare 2. lucru 3. cameră 4. bucătărie 5. somn 6. curte interioară 7. umbrar 8. tainiță / 1. entrance 2. workroom 3. room 4. kitchen 5. bedroom 6. patio 7. shelter 8. cellar

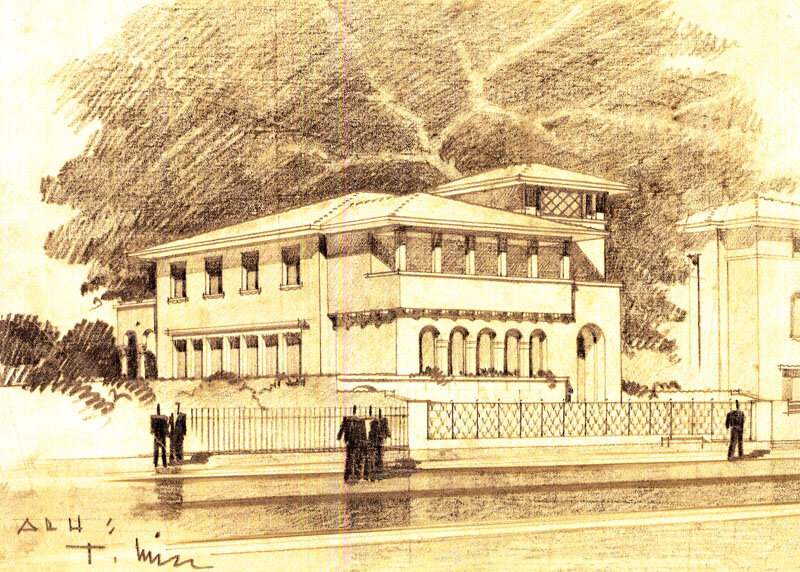

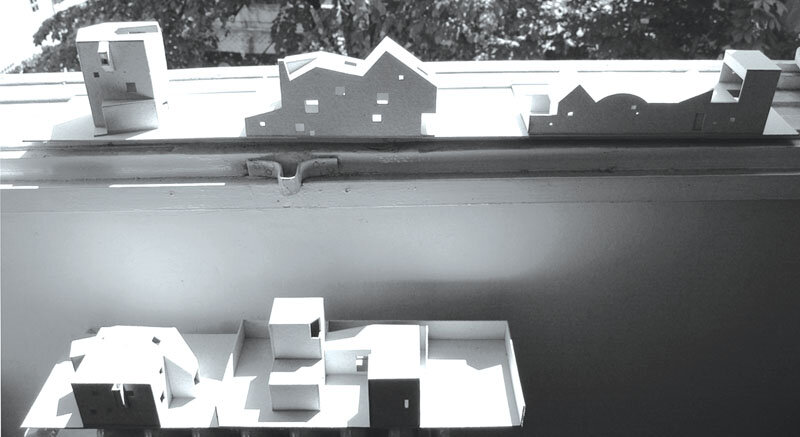

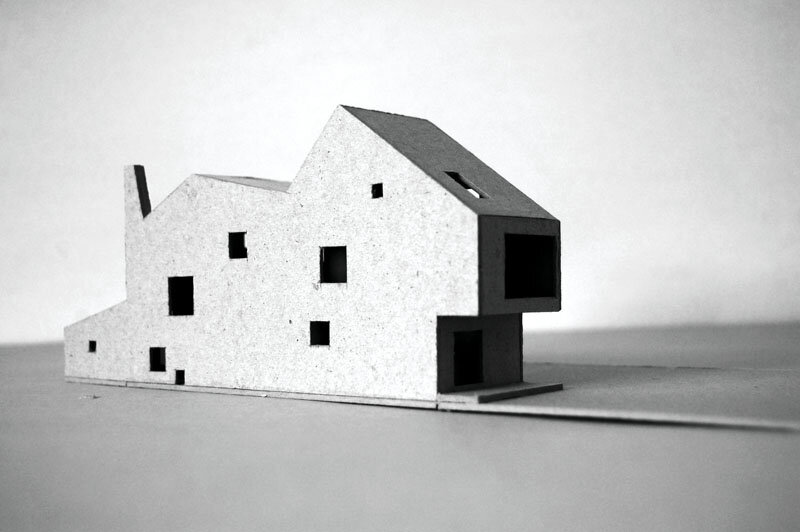

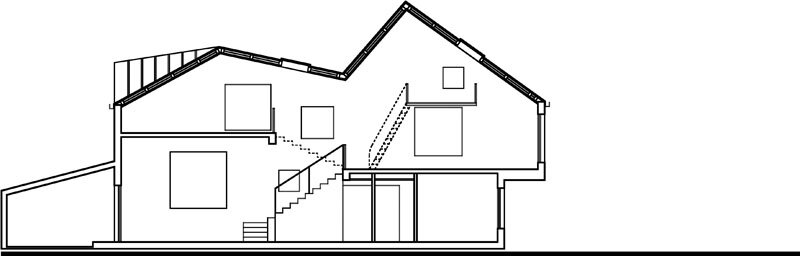

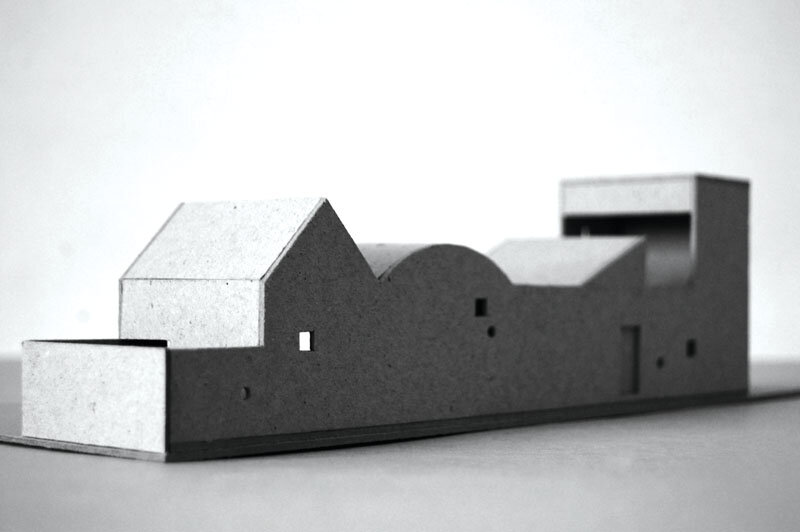

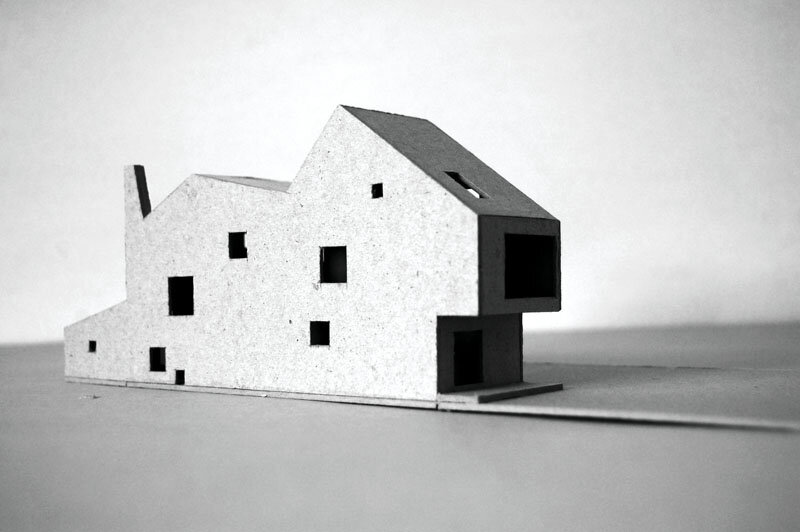

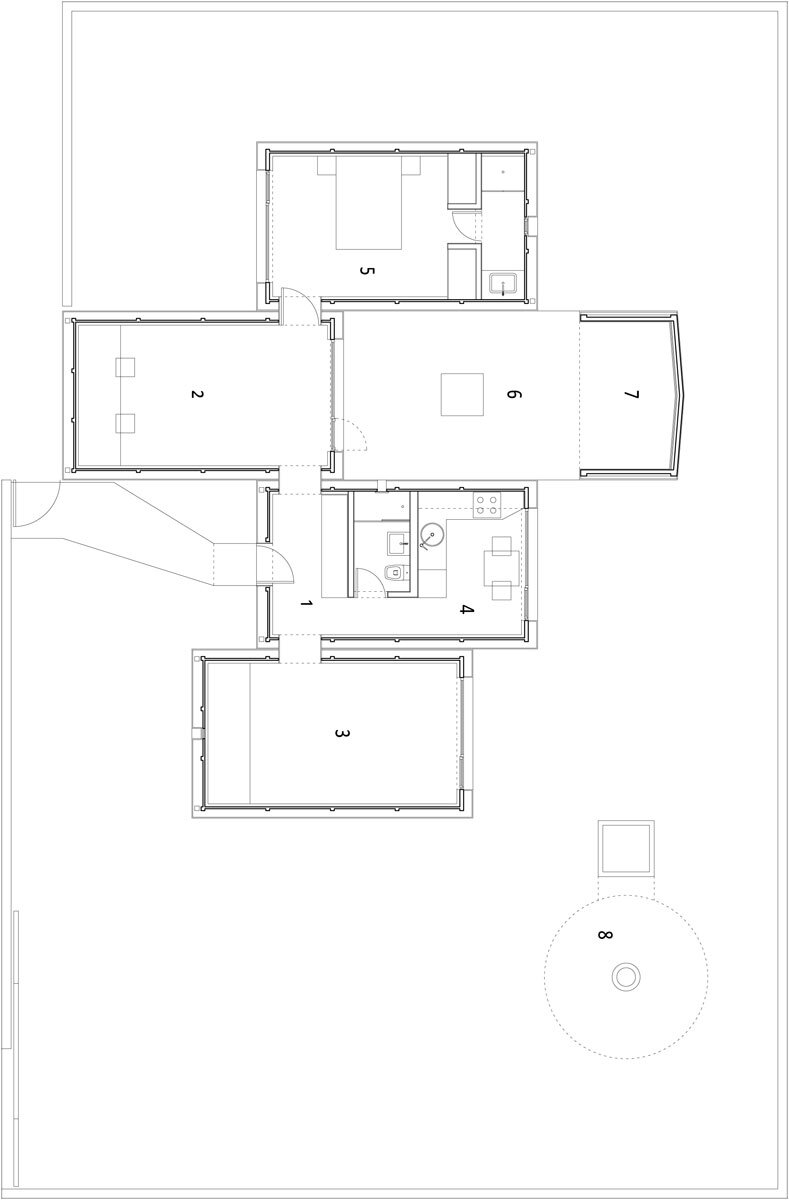

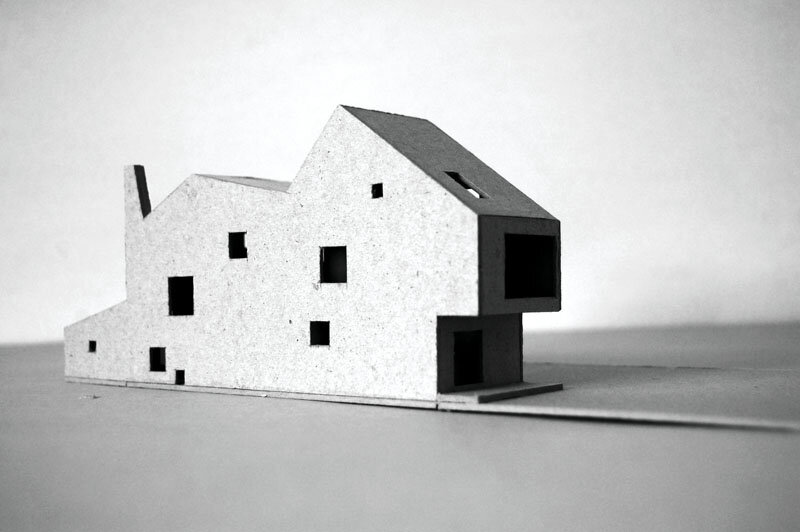

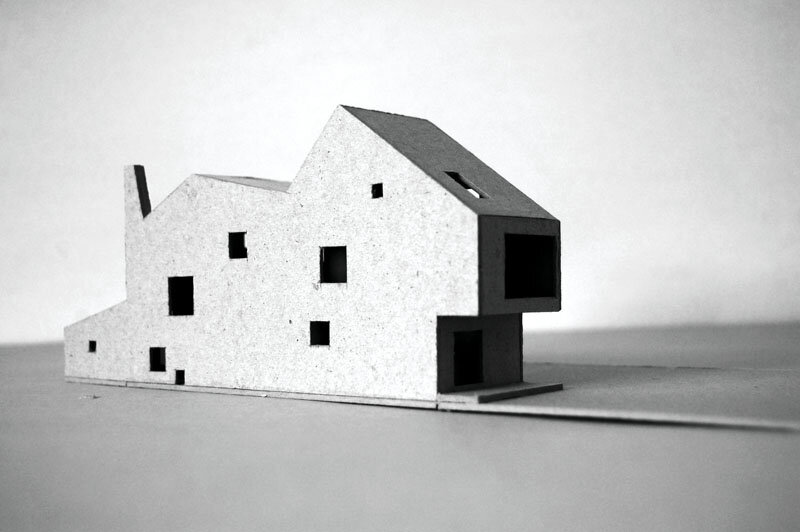

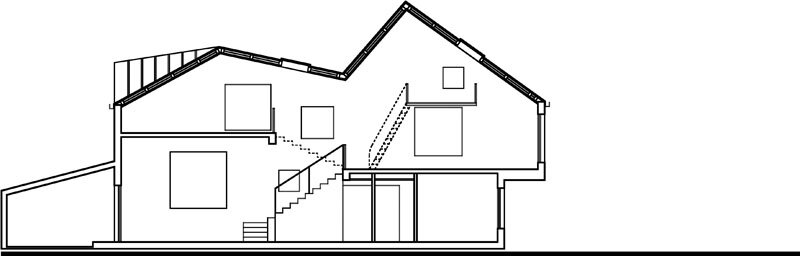

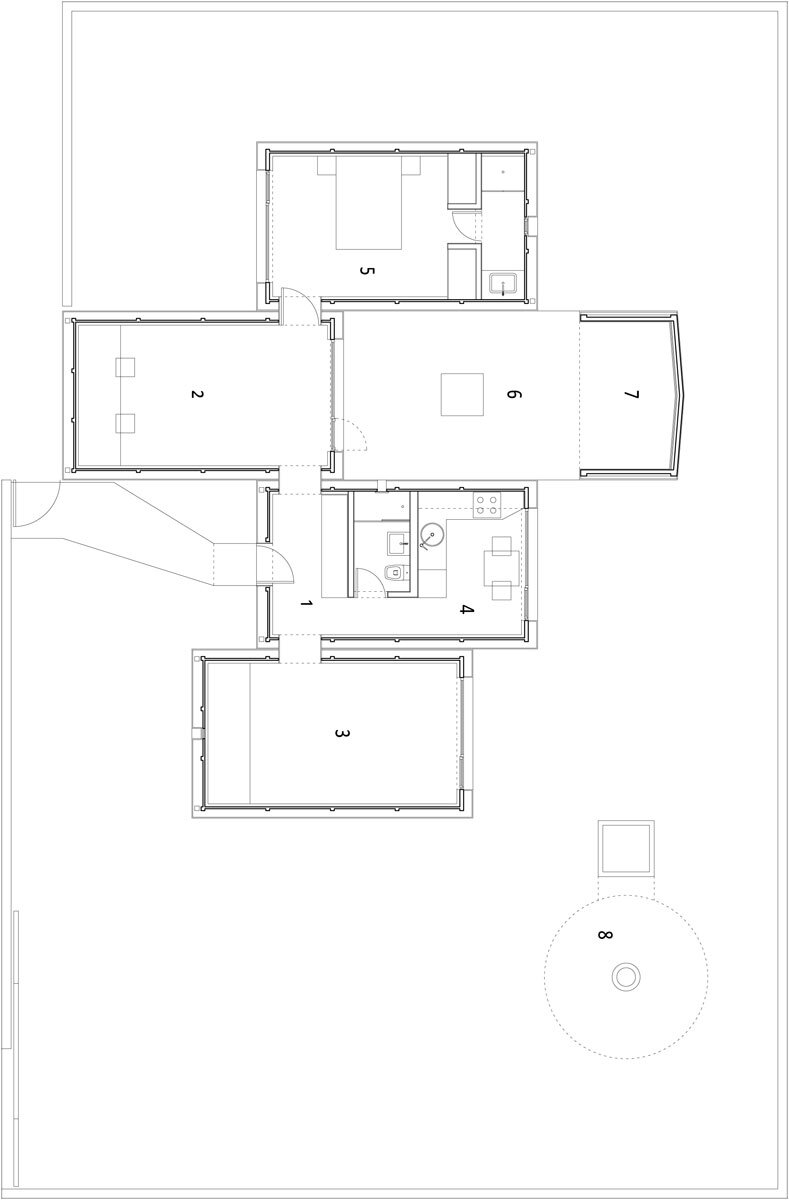

| CASA DE VACANȚĂ DIN AVRAM IANCU |

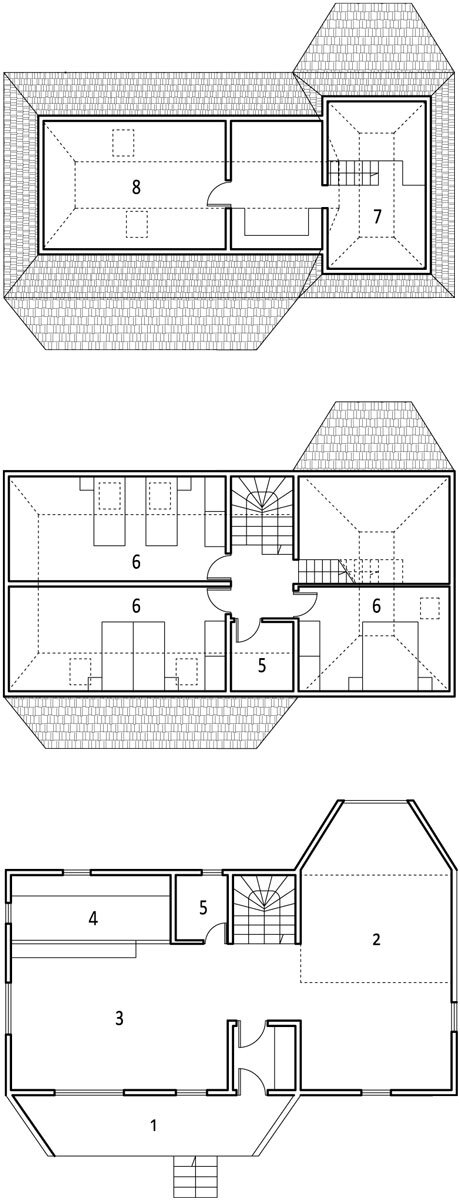

| Domnul Nicolae este ofițer pe un vas cargo. Asta se întâmplă câteva luni pe an, timp în care se poate gândi la multe lucruri. Restul anului este acasă, la Constanța și prin țară. Cu ceva ani în urmă și-a cumpărat un teren în Țara Moților și, trecând prin Alba Iulia, s-a întâmplat să vadă o expoziție despre un concurs de arhitectură. I-a plăcut ceva de-acolo și, nu am elucidat nici azi misterul despre cum și de unde, ne-a căutat la telefon. Domnul Nicolae visa o „căsuță moțească” în satul Avram Iancu. Noi am făcut o casă ca o biserică, învelită în șiță, și o machetă mică. Am împachetat totul și i-am trimis, iar dânsului i-a plăcut mult. A plănuit o vacanță acolo cu familia, nașii și arhitecții. Noi ne-am dat ocupați și de atunci n-am mai avut vești. Și mai e ceva. Ne-a vorbit odată despre pirații somalezi și despre pericolul la care se expun navele ce trec prin apele lor. Așa că, în glumă doar, am zis c-o fi fost răpit de pirați. |

| HOLIDAY HOUSE IN AVRAM IANCU |

| Mr. Nicolae is an officer on a cargo vessel for several months a year, during which time he can think of many things. The rest of the year he is at home, in Constanța, and around the country. Several years ago he purchased a plot of land in Transylvania and, passing through Alba Iulia, accidentally saw an exhibition of an architecture competition. He liked something there and decided to call us; how he did it and from where is a mystery that we have not solved to this day. Mr. Nicolae was dreaming of a “small Transylvanian house” in the Avram Iancu village. We made a house much like a church, all covered in shingles, and a small scale model. We wrapped everything and delivered it to him, and he enjoyed it immensely. He planned a vacation there with his family, the godparents and the architects. We pretended to be busy and haven’t heard of him since. And there is something else. He told us once about the Somalese pirates and the danger incurred by all ships sailing in those waters. So we jokingly assumed that he had probably been kidnapped by pirates. |

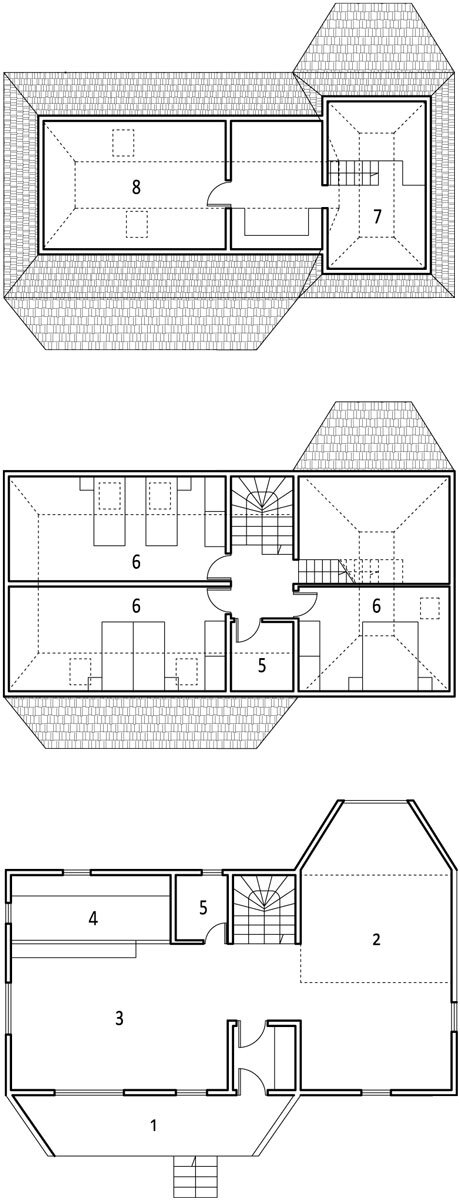

1. camera mare 2. bucătărie 3. camera de oaspeți 4. centrala termică 5. adăpost afară / 1. main room 2. kitchen 3. guest room 4. heating room 5. studio

6. atelier 7. loc pentru somn 8. cu ochii la stele / 6. work room 7. bedroom 8. room towards the sky

1. intrare 2. loc de luat masa 3. camera de zi 4. dormitor și dressing 5. atelier 6. camera de seară 7. grădină 8. terasă 9. loc pentru mașină 10. curte / 1. entrance 2. dining 3. living room 4. bedroom & dressing 5. studio 6. evening room 7. garden 8. terrace 9. parking space 10. courtyard

1. prispa 2. camera de zi 3. sufragerie 4. bucătărie 5. baie 6. dormitor 7. loc de joacă 8. camera copiilor / 1. porch 2. main room 3. dining room 4. kitchen 5. bath room 6. bedroom 7. playroom 8. kids’ room

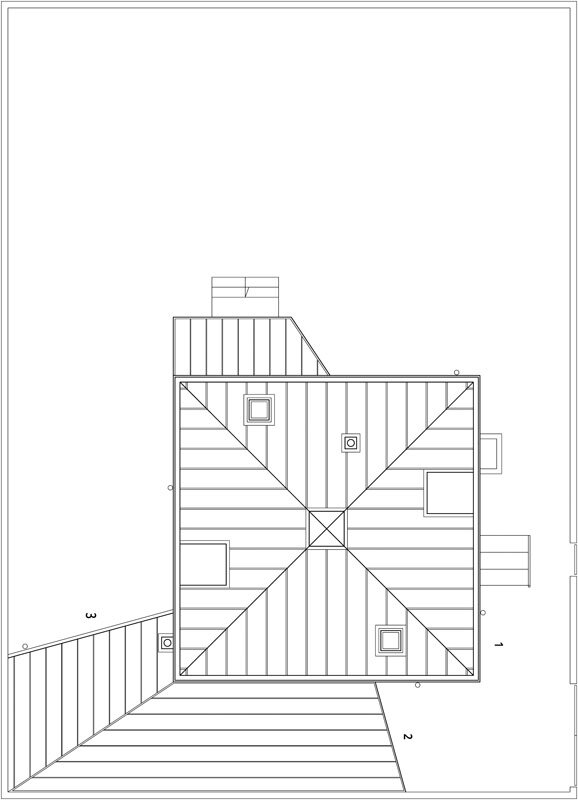

1. casă la Cornetu 2. garaj 3. magazie / 1. house in Cornetu 2. garage 3. storage

1. curte interioară 2. camera de zi 3. scară melc 4. bucătarie 5. dormitor 6. loc de citit 7. loc răcoros 8. terasă pietruită 9. terasă plantată 10. camera din turn 11. balcon / 1. courtyard 2. living room 3. spiral stairs 4. kitchen 5. bedroom 6. reading place 7. cool place 8. paved terrace 9. green terrace 10. tower room 11. balcony

1. intrare 2. lucru 3. cameră 4. bucătărie 5. somn 6. curte interioară 7. umbrar 8. tainiță / 1. entrance 2. workroom 3. room 4. kitchen 5. bedroom 6. patio 7. shelter 8. cellar

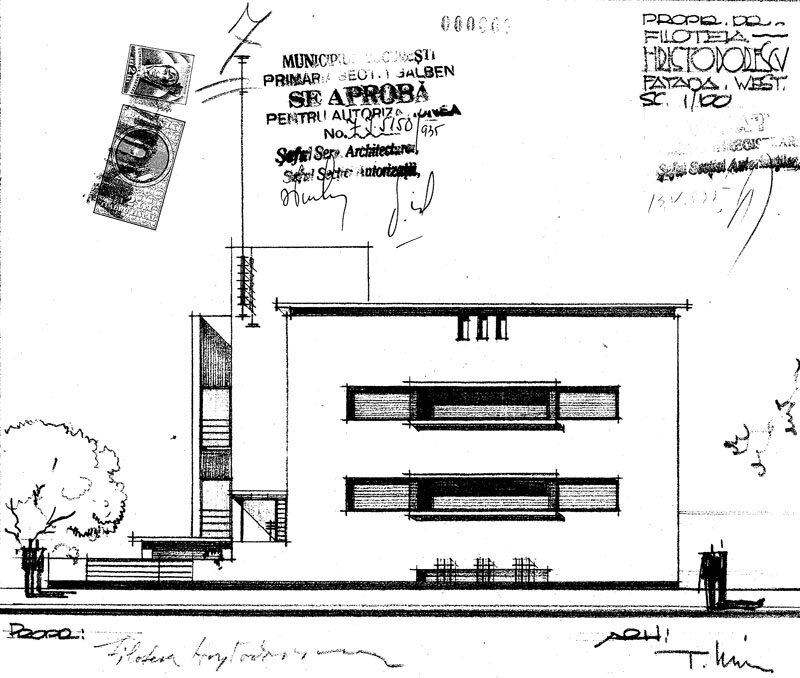

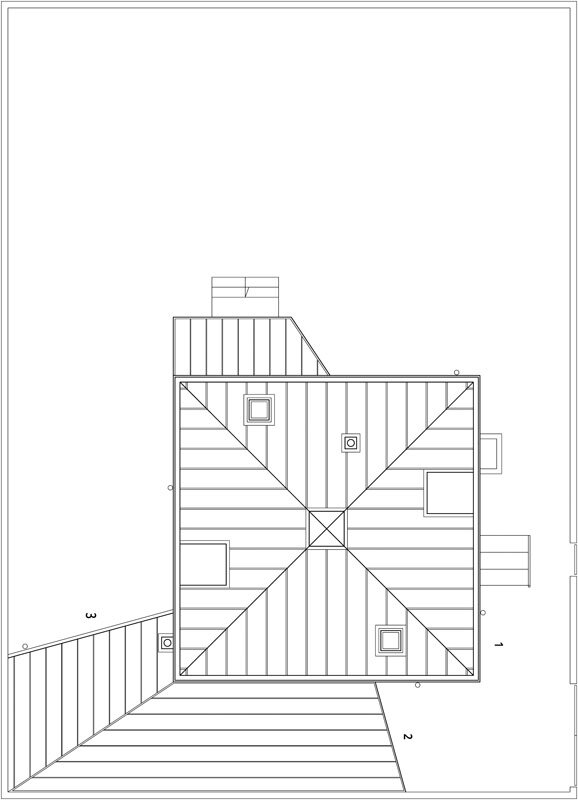

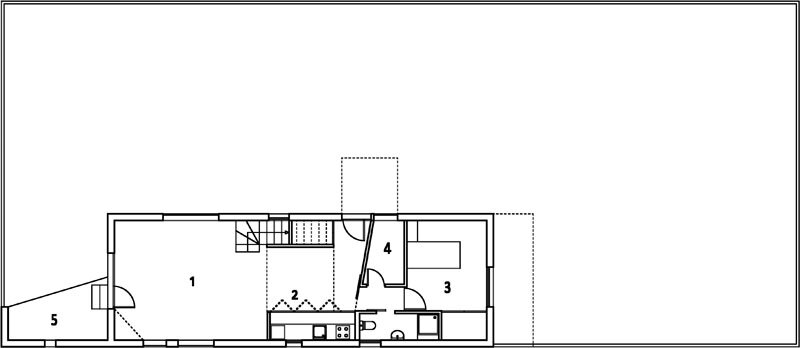

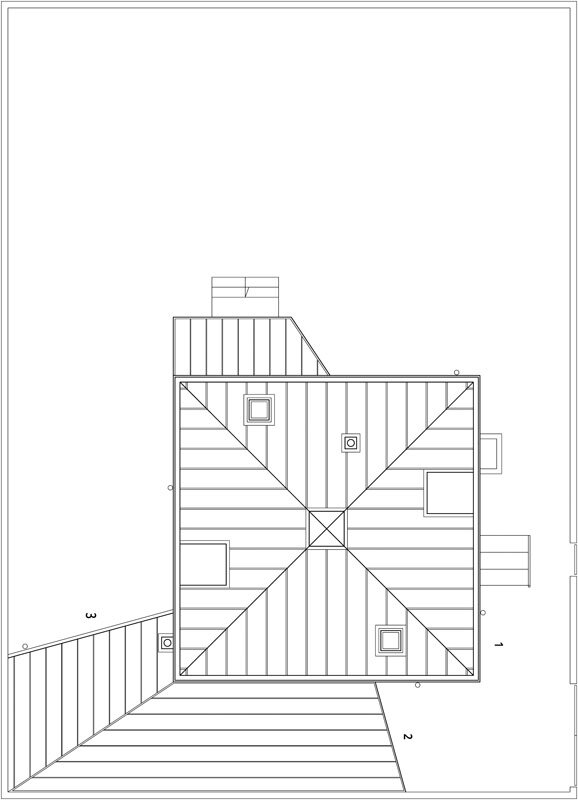

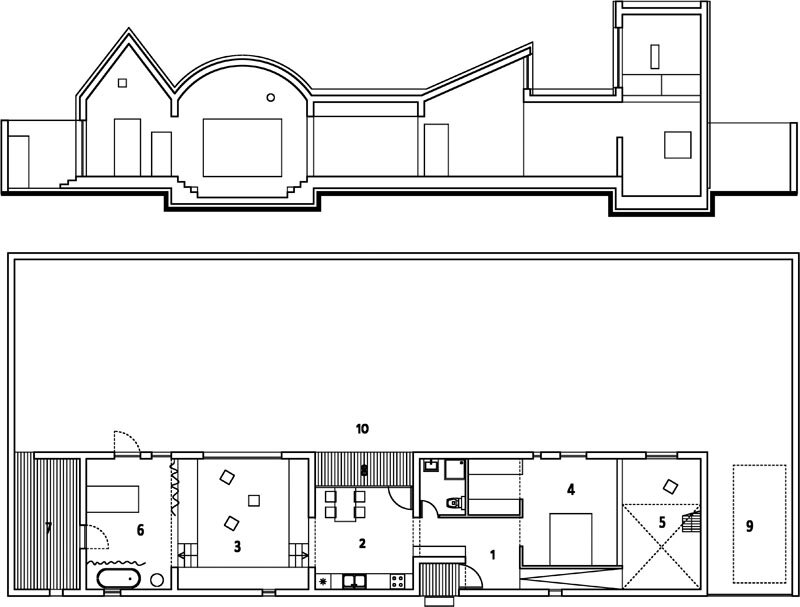

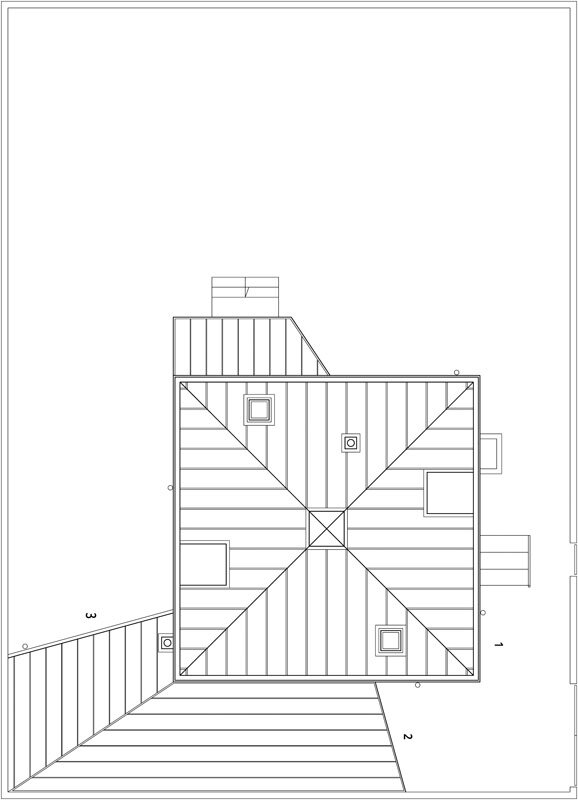

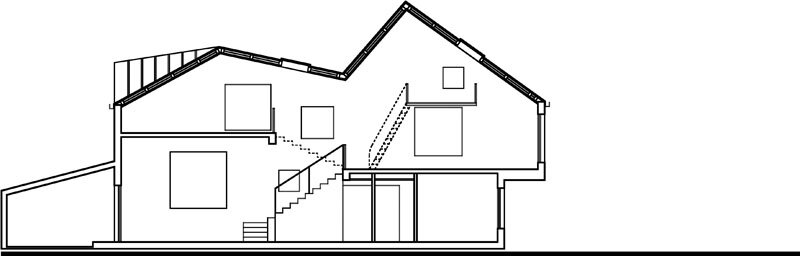

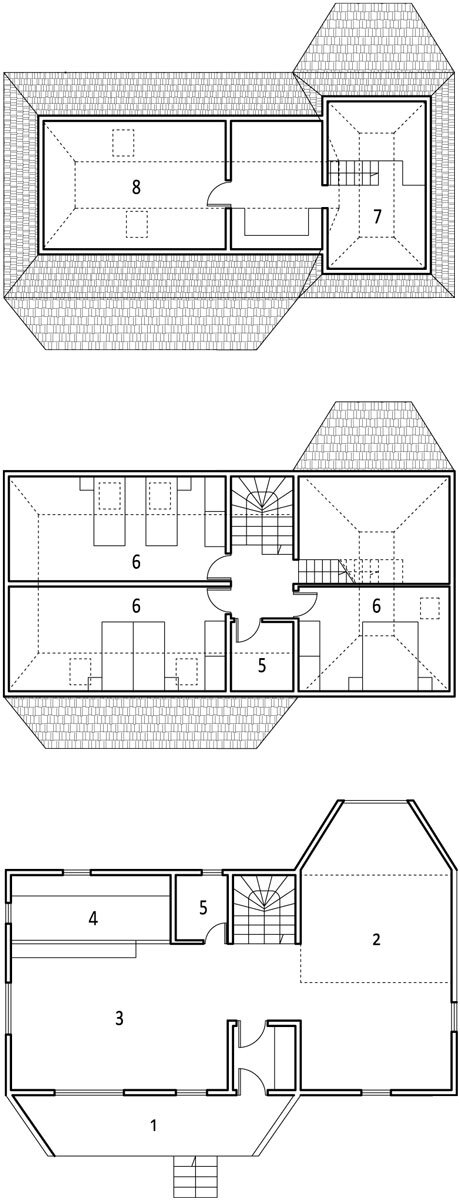

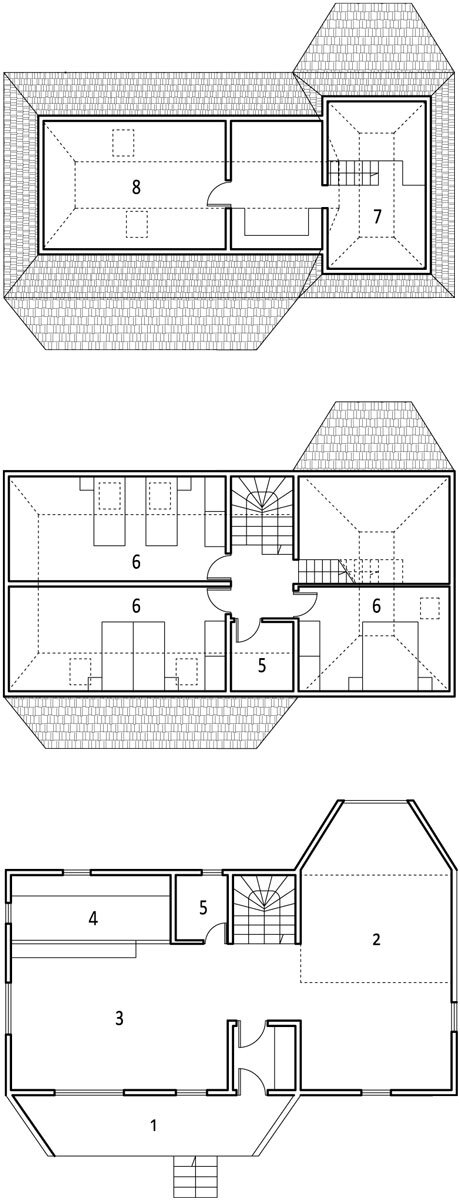

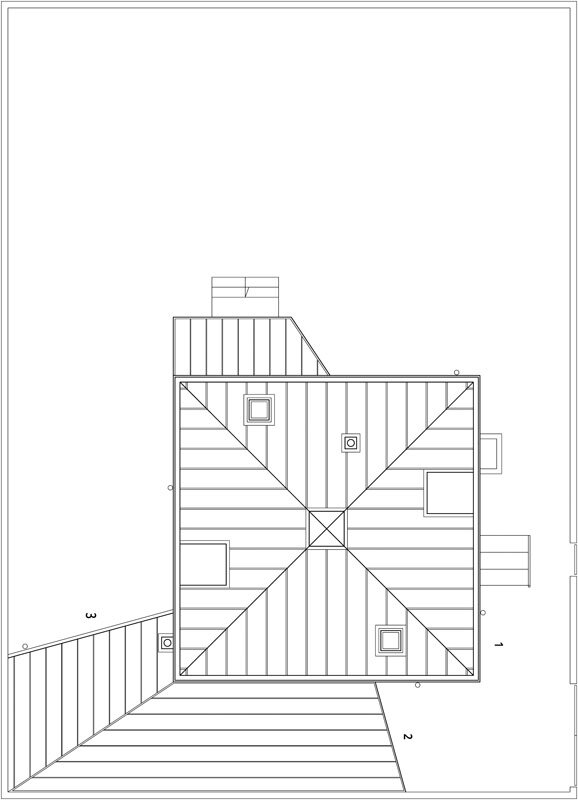

| CASA DE LA CORNETU |

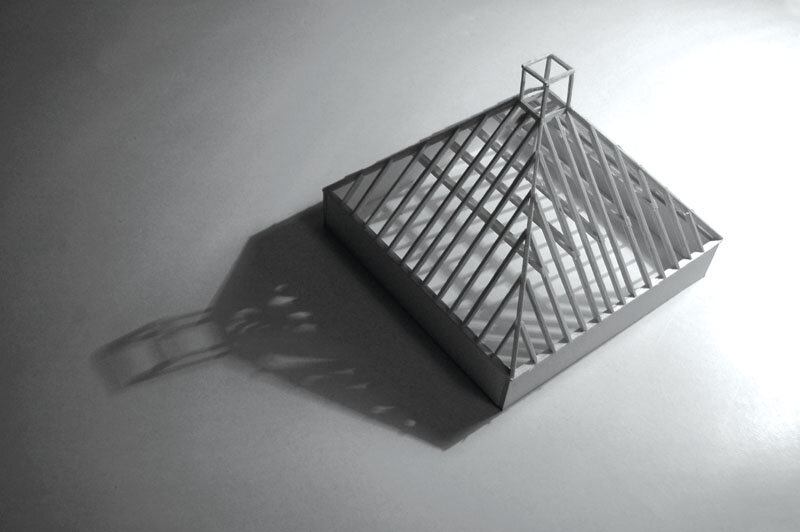

| Răzvan a fost coleg cu doamna Constantin. La început am ezitat, o casă la Cornetu semăna de departe a dosar de autorizație și atât. Până la urmă ne-am întâlnit. Cu Răzvan este foarte ușor să vorbești. Mai apoi am aflat că se ocupă de comunicare. Casa de la Cornetu este o casă pentru el, soție, băiatul cel mare, Victor, băiatul cel mic, Vlad, Varvara, fata pe care și-o doresc, și un Schnauzer rău, adică familia Vasilescu. Am căpătat evident, la prima întâlnire, o schiță de plan pe foaie de mate. Acum șantierul e în toi. Deocamdată ne înțelegem bine, minus două ferestre interioare și niște trepte. Ne adunăm cu ceva emoții în jurul șarpantei, piramidale, înalte, cu lucarne și fereastră mică sus, în creștet. Răzvan îi dă zor până nu se termină vara și banii. |

| THE CORNETU HOUSE |

| Răzvan had been a colleague of Ms. Constantin. At the beginning we were a bit hesitant: a house in Cornetu didn’t promise to amount to much, apart from the preparation of the building permit file. Finally, though, we met. It is very easy to talk to Răzvan. Then we learnt that he was employed in the communication business. The Cornetu house is a house for him, his wife, the eldest boy, Victor, the youngest boy, Vlad, Varvara, the girl they want to have, and a mean Schnauzer, i.e. the Vasilescu family. Naturally, on that very first meeting we were provided with a plan sketched on a sheet from a mathematics notebook. Now the building site is underway. We are getting along just fine with the exception of two interior windows and some stairs. We gather rather nervously around the pyramidal, high roof framing, provided with skylights and a small window on top. Răzvan urges to keep things moving before the summer and the money run out. |

1. camera mare 2. bucătărie 3. camera de oaspeți 4. centrala termică 5. adăpost afară / 1. main room 2. kitchen 3. guest room 4. heating room 5. studio

6. atelier 7. loc pentru somn 8. cu ochii la stele / 6. work room 7. bedroom 8. room towards the sky

1. intrare 2. loc de luat masa 3. camera de zi 4. dormitor și dressing 5. atelier 6. camera de seară 7. grădină 8. terasă 9. loc pentru mașină 10. curte / 1. entrance 2. dining 3. living room 4. bedroom & dressing 5. studio 6. evening room 7. garden 8. terrace 9. parking space 10. courtyard

1. prispa 2. camera de zi 3. sufragerie 4. bucătărie 5. baie 6. dormitor 7. loc de joacă 8. camera copiilor / 1. porch 2. main room 3. dining room 4. kitchen 5. bath room 6. bedroom 7. playroom 8. kids’ room

1. casă la Cornetu 2. garaj 3. magazie / 1. house in Cornetu 2. garage 3. storage

1. curte interioară 2. camera de zi 3. scară melc 4. bucătarie 5. dormitor 6. loc de citit 7. loc răcoros 8. terasă pietruită 9. terasă plantată 10. camera din turn 11. balcon / 1. courtyard 2. living room 3. spiral stairs 4. kitchen 5. bedroom 6. reading place 7. cool place 8. paved terrace 9. green terrace 10. tower room 11. balcony

1. intrare 2. lucru 3. cameră 4. bucătărie 5. somn 6. curte interioară 7. umbrar 8. tainiță / 1. entrance 2. workroom 3. room 4. kitchen 5. bedroom 6. patio 7. shelter 8. cellar

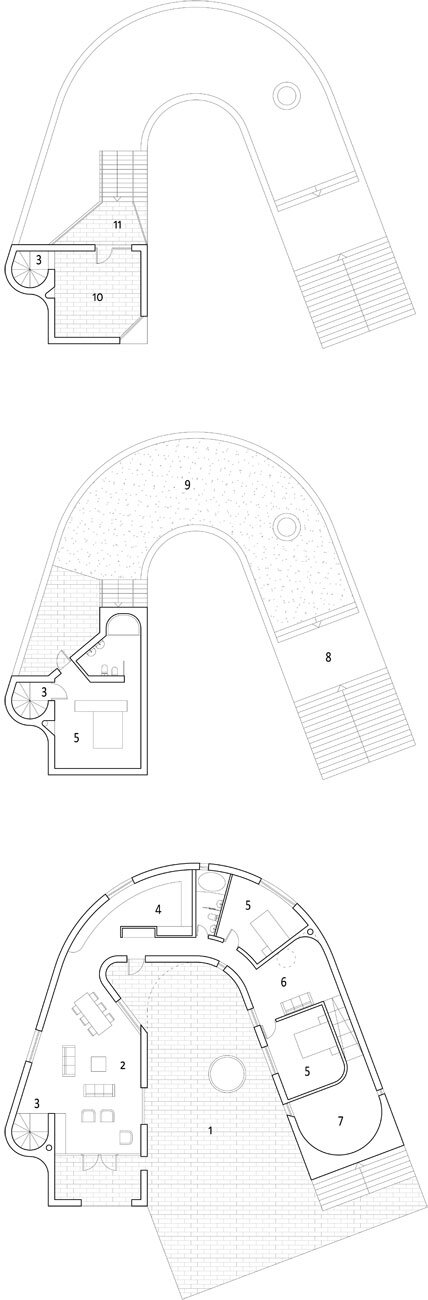

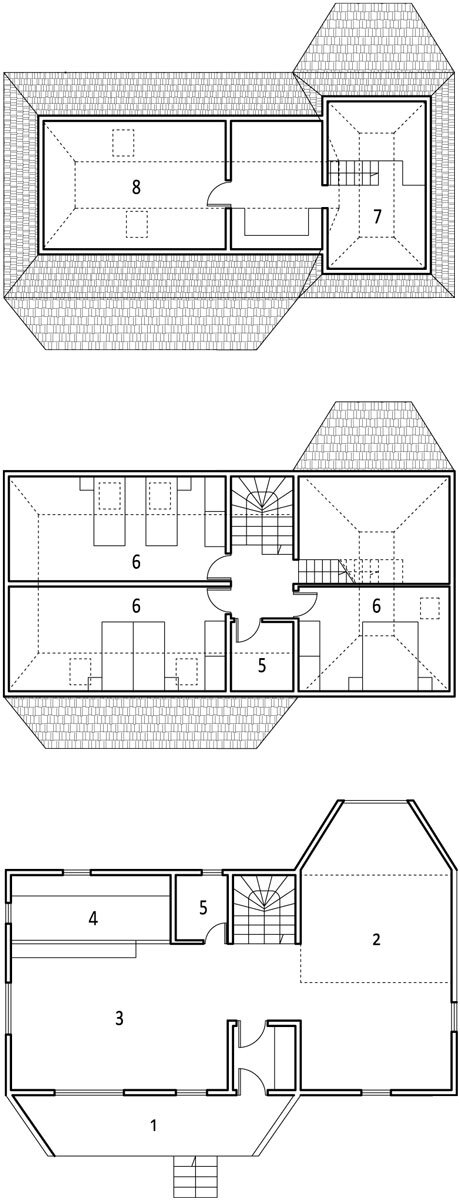

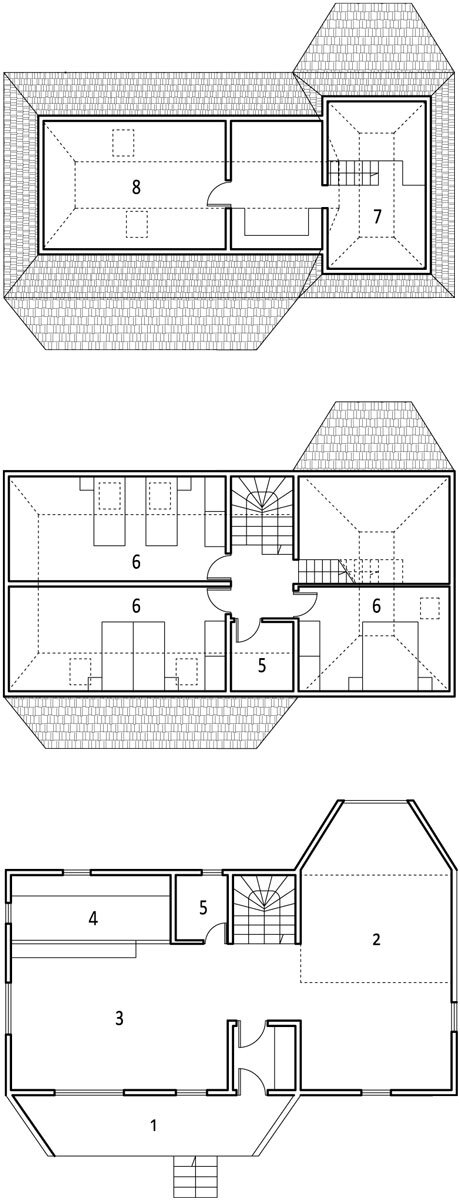

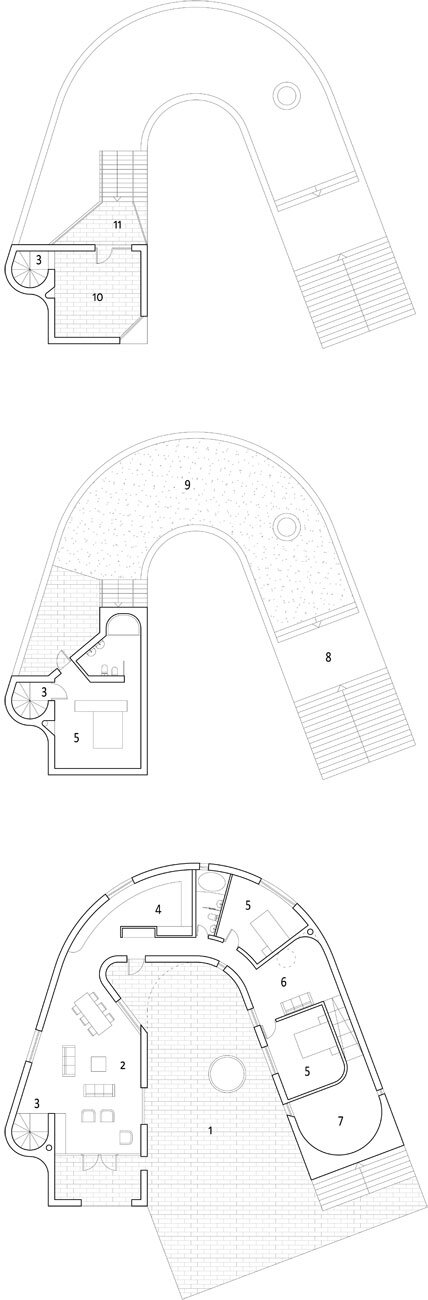

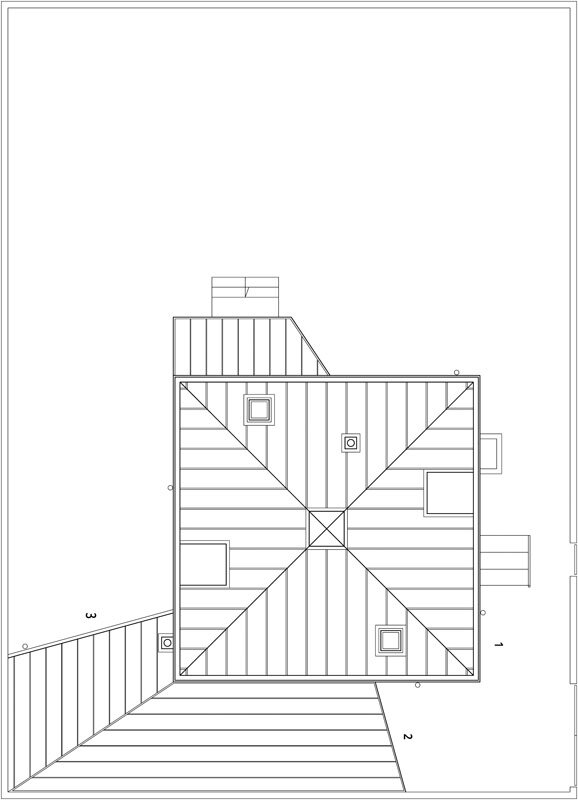

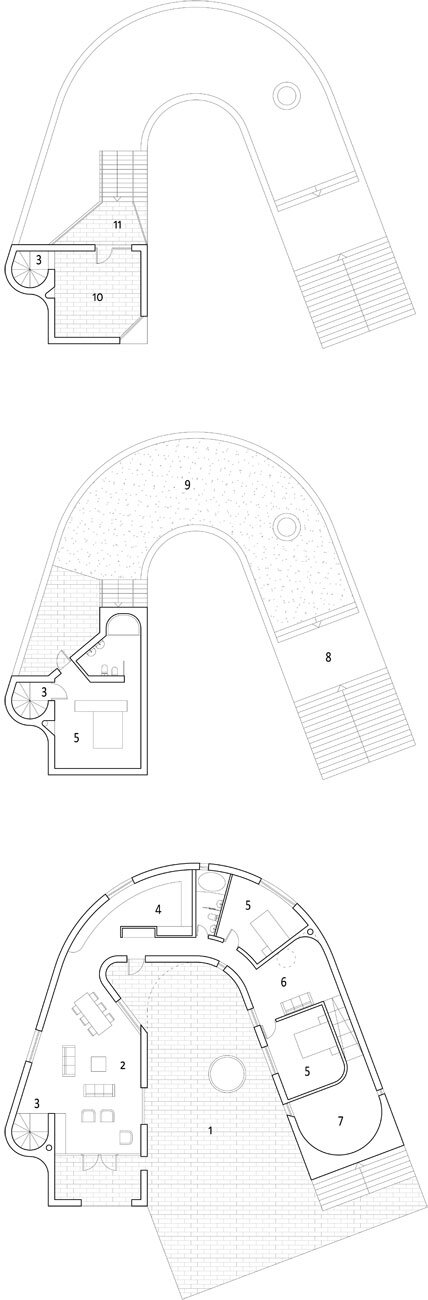

| CASA DE PE VÂRF DE DEAL LA CHIȚORANI |

| Pe Cornel îl știm de mult. Pentru el și familia lui ne-am învârtit o vreme în jurul reabilitării fostei case Bertola. Cornel a cumpărat ceva podgorie pe dealurile de lângă Ploiești și, fiind vorba de o persoană extrem de activă, ideile s-au ținut lanț. Pentru casa veche, pe rând: o pensiune, o casă de vacanță, o locuință permanentă. Imediat lângă ea: o vinărie, o pensiune, o casă de nunți, câteva locuințe adunate într-un bloculeț. Iar mai apoi, pe un vârf de deal, o casă. Casa „potcoavă” este o casă de cărămidă cu curte, turn, trepte, iarbă și rotunjimi. Cosmin a desenat-o într-o zi pe-o piatră, în curte la Radu Vodă. Cornel n-a mai întrebat de mult de ea. |

| THE HOUSE ON TOP OF THE CHIȚORANI HILL |

| We have known Cornel for a long time. For him and his family we did a lot of research for the restoration of the former Bertola hose. Cornel purchased a vineyard on the hills near Ploiești and, as he is a very active person, the ideas came one after the other. For the old house, one by one, there came: a pension, a holiday house, a permanent dwelling. Right next to it: a wine cellar, a pension house, a wedding house, several dwellings gathered in a small apartment block. Then, on top of the hill, there rises a house. The “horseshoe” house is a brick house with yard, tower, stairs, grass and round edges. Cosmin drew it one day on a rock, in Radu Vodă Monastery’s courtyard. Cornel has not been asking about it for a long time. |

1. camera mare 2. bucătărie 3. camera de oaspeți 4. centrala termică 5. adăpost afară / 1. main room 2. kitchen 3. guest room 4. heating room 5. studio

6. atelier 7. loc pentru somn 8. cu ochii la stele / 6. work room 7. bedroom 8. room towards the sky

1. intrare 2. loc de luat masa 3. camera de zi 4. dormitor și dressing 5. atelier 6. camera de seară 7. grădină 8. terasă 9. loc pentru mașină 10. curte / 1. entrance 2. dining 3. living room 4. bedroom & dressing 5. studio 6. evening room 7. garden 8. terrace 9. parking space 10. courtyard

1. prispa 2. camera de zi 3. sufragerie 4. bucătărie 5. baie 6. dormitor 7. loc de joacă 8. camera copiilor / 1. porch 2. main room 3. dining room 4. kitchen 5. bath room 6. bedroom 7. playroom 8. kids’ room

1. casă la Cornetu 2. garaj 3. magazie / 1. house in Cornetu 2. garage 3. storage

1. curte interioară 2. camera de zi 3. scară melc 4. bucătarie 5. dormitor 6. loc de citit 7. loc răcoros 8. terasă pietruită 9. terasă plantată 10. camera din turn 11. balcon / 1. courtyard 2. living room 3. spiral stairs 4. kitchen 5. bedroom 6. reading place 7. cool place 8. paved terrace 9. green terrace 10. tower room 11. balcony

1. intrare 2. lucru 3. cameră 4. bucătărie 5. somn 6. curte interioară 7. umbrar 8. tainiță / 1. entrance 2. workroom 3. room 4. kitchen 5. bedroom 6. patio 7. shelter 8. cellar

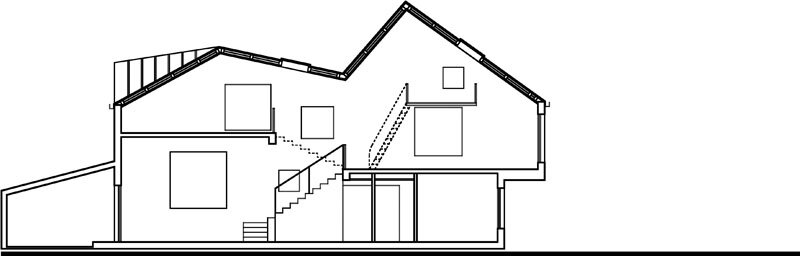

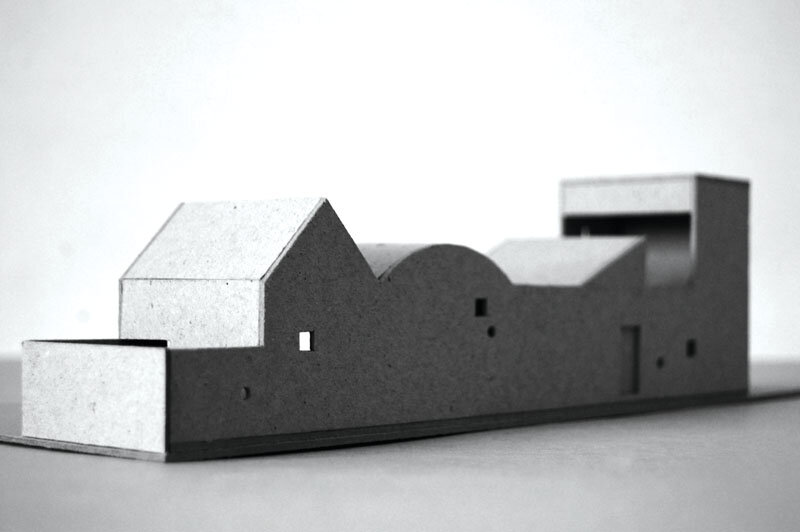

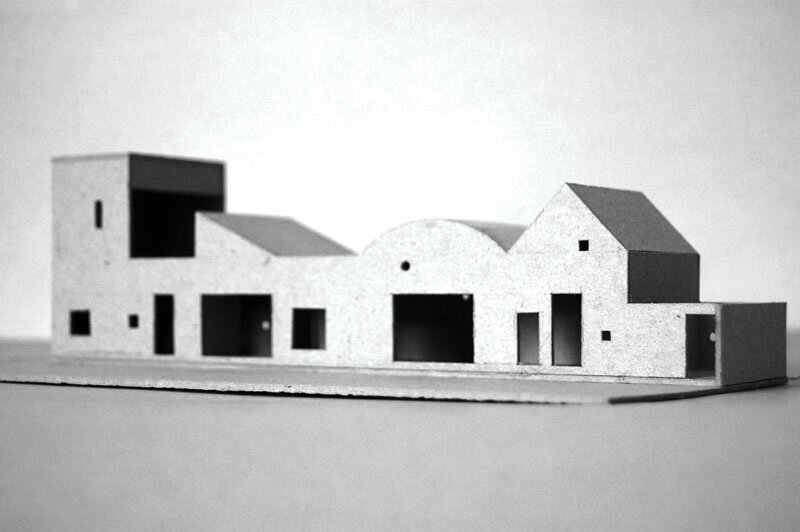

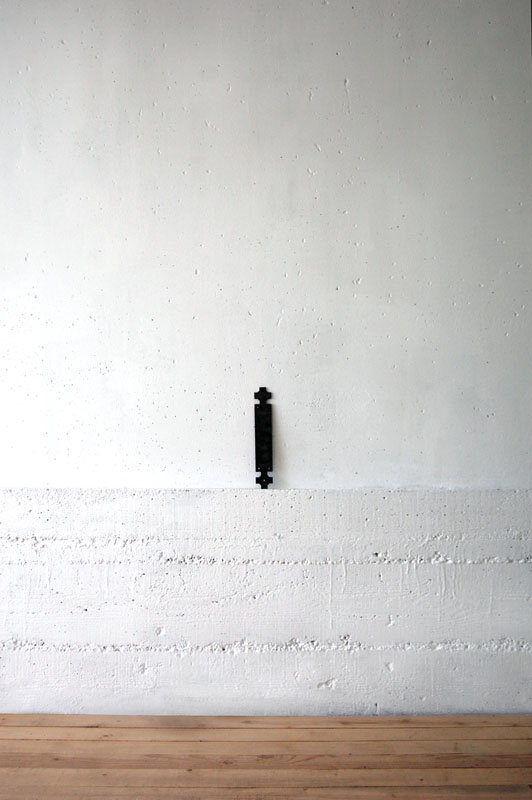

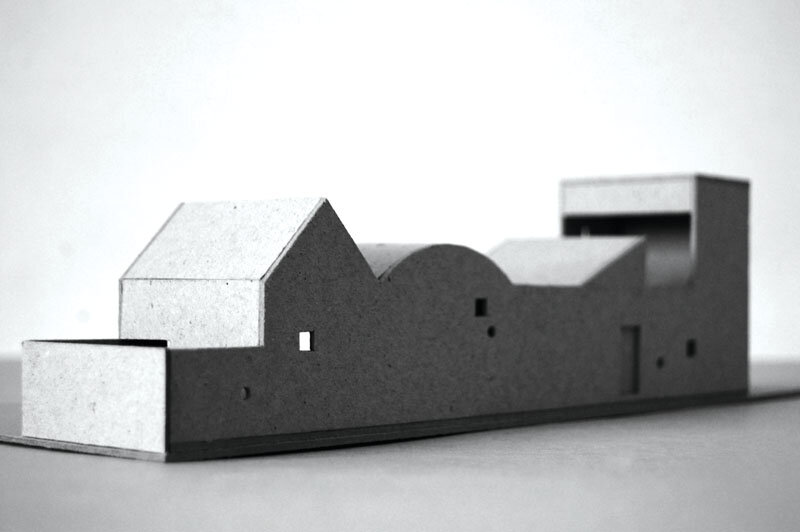

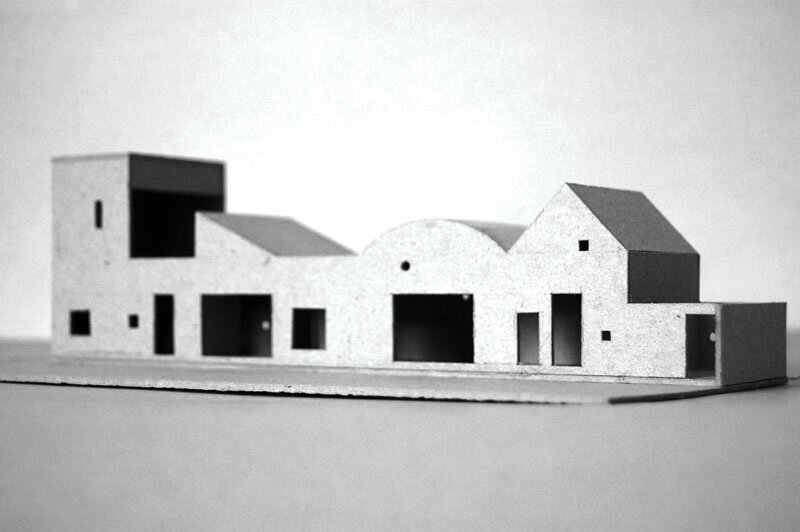

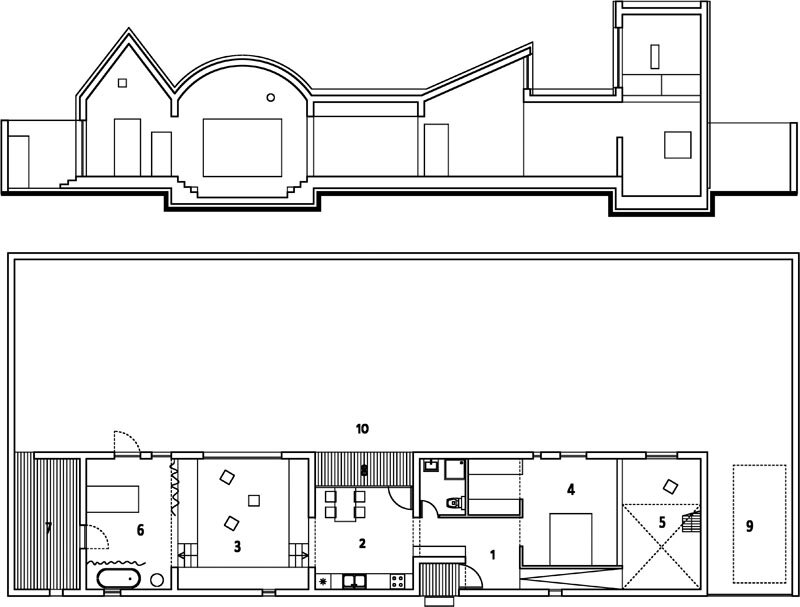

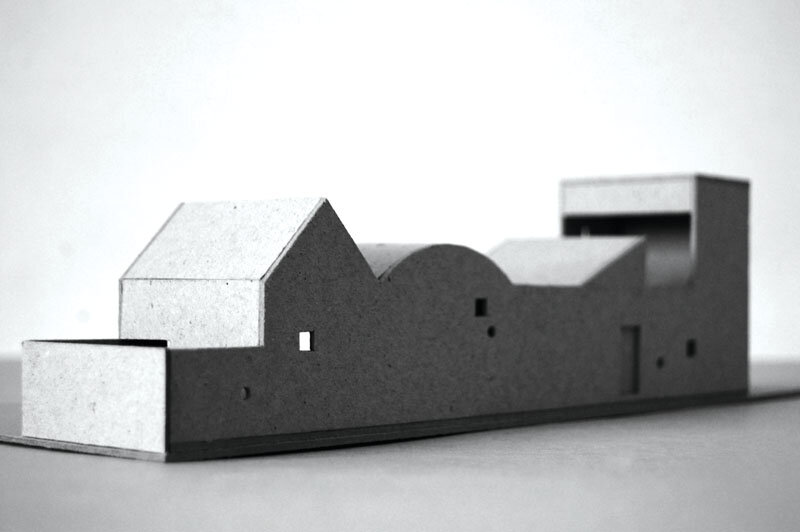

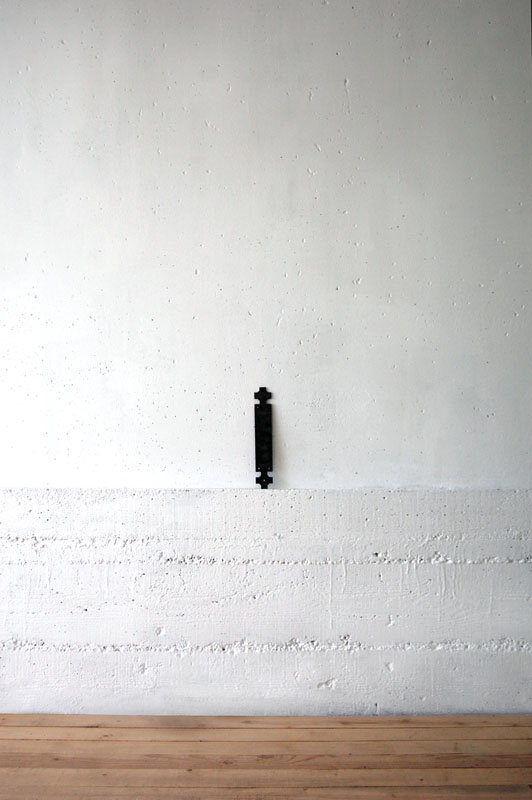

| CASA DIN GARAJE DE LA BRAGADIRU |

| Casa de la Bragadiru e casa noastră. Cosmin a cumpărat terenul prin 2004 și primul garaj prefabricat „Granitul” în 2007. La început și-a petrecut o vreme în jurul unor idei frumoase: o casă ca un cuptor, o casă turn înfășurată într-o scară. În cele din urmă totul a devenit mult prea greu. A-ți face propria casă ca arhitect, unde să oprești visarea? Decizia a fost drastică: va fi o casă din garaje recuperate al cărei proiect să-l înceapă Cristina. Oarecum depășită de sarcina încredințată, Cristina a umplut două caiete cu schițe de asamblare a garajelor. Ne-am consultat. Cosmin a propus garajul vertical, „monumentalul”. S-au hotărnicit pe rând o curte pentru atelier, curtea dormitorului, curtea de intrare și curtea mare. Ne-am apucat de șantier. A durat mult, foarte mult. Am învățat multe. Ne-am gândit că poate e nevoie de experiența facerii propriei case pentru a putea înțelege nevoia și greutatea altuia de a-și construi o casă. Acum e pe sfârșite. Garajele sunt albe și au obloane mari din tablă expandată, albe și ele. Pe „monumental” urcă viță sălbatică. Cosmin a zidit o pivință aproape îngropată, cu o cupolă și oculus. Cărămida recuperată se vede înăuntru, iar deasupra crește iarbă. Una dintre cele trei sălcii plantate toamna trecută a prins rădăcini. |

| THE GARAGE HOUSE IN BRAGADIRU |

| The Bragadiru house is our house. Cosmin purchased the land in 2004 and the first prefabricated garage “Granitul” in 2007. At the beginning, he spent some time conceiving some nice ideas: a house like an oven, a tower house wrapped in a stairway. Eventually, everything became very difficult. As an architect who wants to make his own house, where do you draw the line and stop dreaming? The decision was severe: it will be a house made of recovered garages, whose design had to be commenced by Cristina. Somewhat overwhelmed by the task, Cristina filled two notebooks with sketches for the assembly of the garages. We had some consultations. Cosmin proposed the vertical garage, the “monumental”. We decided, one by one, upon a yard for the studio, the bedroom’s yard, the entrance yard and the large main yard. So we kicked off the building site. It lasted a long, long time. We learnt many things. We thought that maybe it took the experience of making your own house in order to be able to understand another person’s need and hardships in building a house. Now it is almost finished. The garages are white and have been equipped with large shutters made of expanded iron plate, also painted white. The “monumental” is clad in wild grapevine. Cosmin built an almost buried cellar with a dome and an oculus. The recovered brick can be spotted inside; it is covered in grass on the outside. One of the three willows planted last autumn has already taken root. |

1. camera mare 2. bucătărie 3. camera de oaspeți 4. centrala termică 5. adăpost afară / 1. main room 2. kitchen 3. guest room 4. heating room 5. studio

6. atelier 7. loc pentru somn 8. cu ochii la stele / 6. work room 7. bedroom 8. room towards the sky

1. intrare 2. loc de luat masa 3. camera de zi 4. dormitor și dressing 5. atelier 6. camera de seară 7. grădină 8. terasă 9. loc pentru mașină 10. curte / 1. entrance 2. dining 3. living room 4. bedroom & dressing 5. studio 6. evening room 7. garden 8. terrace 9. parking space 10. courtyard

1. prispa 2. camera de zi 3. sufragerie 4. bucătărie 5. baie 6. dormitor 7. loc de joacă 8. camera copiilor / 1. porch 2. main room 3. dining room 4. kitchen 5. bath room 6. bedroom 7. playroom 8. kids’ room

1. casă la Cornetu 2. garaj 3. magazie / 1. house in Cornetu 2. garage 3. storage

1. curte interioară 2. camera de zi 3. scară melc 4. bucătarie 5. dormitor 6. loc de citit 7. loc răcoros 8. terasă pietruită 9. terasă plantată 10. camera din turn 11. balcon / 1. courtyard 2. living room 3. spiral stairs 4. kitchen 5. bedroom 6. reading place 7. cool place 8. paved terrace 9. green terrace 10. tower room 11. balcony

1. intrare 2. lucru 3. cameră 4. bucătărie 5. somn 6. curte interioară 7. umbrar 8. tainiță / 1. entrance 2. workroom 3. room 4. kitchen 5. bedroom 6. patio 7. shelter 8. cellar