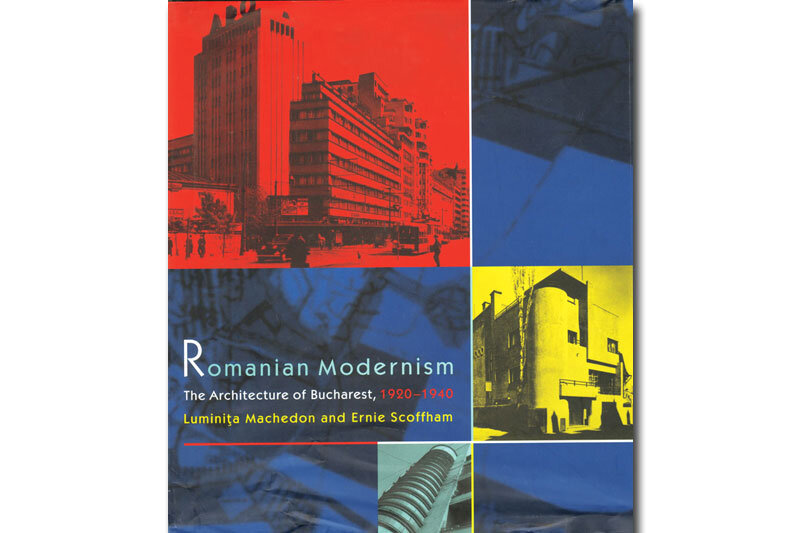

Din nou Edgar Quinet 6

Again Edgar Quinet 6

| Pe strada Edgar Quinet, vizavi de Capșa, din frontul continuu al unor imobile înalte de apartamente și birouri se detașează o clădire-accent. Chiar și trecătorul grăbit, neatent la peisajul urban, remarcă probabil cele cinci cariatide masive retezate de la ombilic în sus, din care nu au mai rămas decât drapeurile inferioare, rigide ca niște caneluri, și peplum-ul înnodat în jurul șoldurilor. Nu le-am aflat povestea, dar putem zâmbi imaginându-ne pudibonderia încruntată a unui activist mărunt care, scandalizat de bustul dezgolit (poate) al acestor géantes, mărturie a putreziciunii burghezo-moșierești și prezență blasfematoare în spațiul aseptic al moralei socialiste, va fi venit cu ideea mutilării lor salutare.

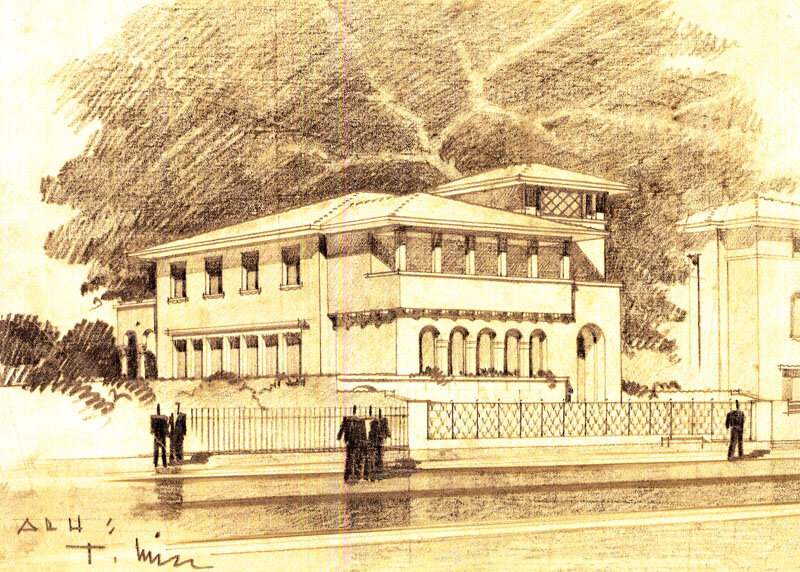

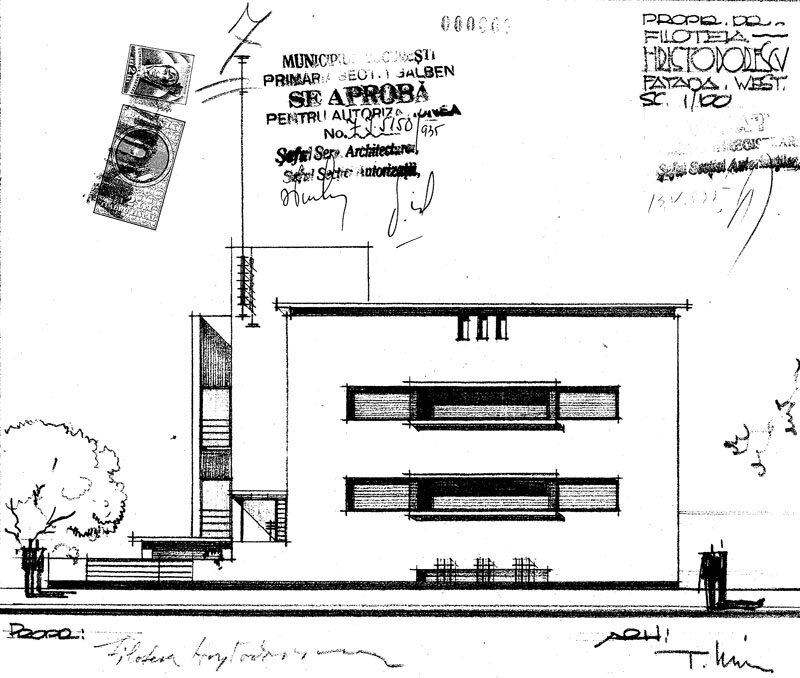

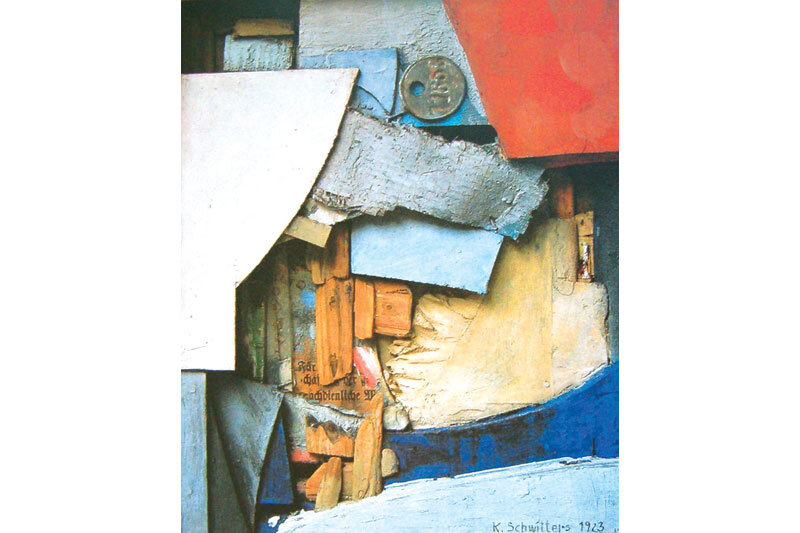

Însă, la o privire mai atentă, parterul ne frapează imediat prin noblețea materialelor și prețiozitatea „accesoriilor”, iar de pe latura opusă a străzii înguste sesizăm monumentalitatea ponderată a unei fațade de factură clasică, interpretată într-o manieră modernă și rafinată. Este, de fapt, un exemplar reprezentativ pentru cultura arhitecturală a perioadei interbelice târzii, în speță pentru formula de sinteză, specifică epocii, între estetica Art Deco și clasicismul monumental. Totuși, comparând planurile istorice cu planul cadastral actual, se poate presupune că edificiul de astăzi este o remodelare sau o reconstrucție a unui imobil mai vechi, cu o amprentă la sol întrucâtva asemănătoare. De altfel, în zona centrală a Bucureștiului, numeroase clădiri, în special din sec. XX, se ridică pe fundațiile, pivnițele sau structura de rezistență a unor clădiri anterioare, iar fațadele și volumetriile lor „moderne” se adaptează tipurilor planimetrice tradiționale ale vernacularului urban. Ce informații ne furnizează o incursiune sumară în istoricul zonei și al străzii? Tronsonul dintre Calea Victoriei și strada Academiei apare pentru prima dată în planurile maiorului Pappasoglu din 1870-1875, cu numele de Strada Nouă. Mica străpungere traversa vechiul domeniu al marelui vornic Slătineanu, unde funcționau deja, de pe la 1830, un teatru („Teatrul vechi” din strada Academiei) și faimoasa sală de bal „Momolo” sau „Slătineanu”, cu birt și cofetărie la parter, amenajate chiar în casele Slătineanu dinspre Podul Mogoșoaiei și cumpărate de frații Capșa în 1868. Până la sfârșitul sec. al XIX-lea, cele două fronturi ale noii străzi se completează, în timp ce arterele mai importante din jur își păstrează regimul deschis. În Planul Institutului Geografic al Armatei din 1895-1899 și în planul cadastral din 1911, parcela actuală de la nr. 6, care are aceeași formă ca și astăzi, este ocupată de o clădire în formă de U, cu o planimetrie specifică vernacularului urban bucureștean de secol XIX: un corp compact dispus la aliniament și ocupând întreaga lățime a lotului, articulat cu două bare perpendiculare în spate, la care se adaugă anexele pe fund de lot. Clădirea, cu parter și etaj, poate fi observată și în fotografiile aeriene realizate în 1927 de Compagnie Aérienne Française. Dacă, din punct de vedere stilistic, clădirea actuală cu șase niveluri se afiliază incontestabil la estetica clasicizantă a anilor 1930, amprenta la sol din planul cadastral trădează reminiscențe evidente ale perioadelor anterioare (ceea ce induce necesitatea unei cercetări de teren și de arhivă): același corp compact spre stradă, ușor mai dezvoltat în adâncime și articulat pe latura de vest a parcelei cu un singur corp secundar, mai îngust și mai scund. La cele două, care ar putea fi ridicate pe conturul unei părți din vechea clădire, se adaugă un alt corp îngust pe fund de lot, în locul anexelor. Noua clădire, beneficiind de amplasarea într-o zonă activă de instituții și afaceri, a fost gândită din start ca sediu de birouri - după cum o confirmă și Ghidul oficial al orașului din 1934, în care, la adresa Edgard (sic!) Quinet nr. 6, figurează Banca Albina, dar și Societatea Kodak. Asocierea celor două sedii ar putea explica schema compozițională disimetrică a fațadei, corespunzând probabil necesităților spațial-funcționale ale interiorului: cele două accese diferențiate ca importanță, dispuse lateral la parter, determină la nivelurile superioare travee, de asemenea diferențiate ca dimensiune și tratare, care încadrează motivul central. În plus, ornamentele figurative ale portalului din dreapta – stupi și albine – semnalează explicit identitatea unuia dintre ocupanții clădirii. Revenind astfel la fațada care se înscrie perfect în frontul continuu al străzii, dar iese în evidență ca tratare plastică, se remarcă monumentalitatea jovială pe care o afișează - lipsită de ostentație, dar elegantă și chiar sofisticată. Sinteza acestor atribute se datorează unei abile fuziuni între limbajul clasic, preferat în epocă pentru clădirile publice cu funcțiune de reprezentare, și estetica Art Deco, favorizată în cazul imobilelor de birouri și apartamente, al hotelurilor și spațiilor comerciale, al programelor pentru spectacole și loisir. Recuperarea paradigmei clasice în anii 1930 are o dublă explicație. Pe de o parte, întreaga perioadă post-Belle Époque se caracterizează printr-un suflu clasicizant (sintetizat de Jean Cocteau în formula retour à l’ordre), care apare ca o reacție legitimă față de excesele formale ale academismului târziu și ale stilurilor „1900”, dar și față de experimentele provocatoare ale avangardelor. Pe de altă parte, criza generalizată în perioada interbelică se traduce în plan estetic prin apelul la morala, rigoarea și austeritatea pe care le evocă valorile clasice, iar în plan politico-economic – printr-o tendință de întărire a autorității statului, materializată în arhitectura monumentală a instituțiilor publice, indiferent dacă acestea aparțin unor regimuri dictatoriale sau democratice. Recursul la clasicismul academic, acompaniat în artele plastice de un realism cu tentă propagandistică, exprimă nevoia de [auto]reprezentare concretă, inteligibilă pentru masele largi, a Puterii statale și a ordinii pe care o impune societății – de unde denumirea generică de „realism social” a acestei culturi intens ideologizate. Discursul solemn al clasicismului monumental este însă adesea temperat prin „surdina” estetizantă și stenică a limbajului Art Deco, virând spre o expresie stilistică pe care o putem numi „clasicism deco”. Cei doi termeni ai sintagmei nu sunt contradictorii: ca ipostază soft a modernismului interbelic, fenomenul deco promovează toleranța – chiar reverența – fața de tradiție, pe lângă comunicativitate și primatul plăcerii estetice imediate asupra principiilor abstracte, ceea ce explică succesul de care s-a bucurat în epocă. De altfel, estetica Art Deco, prin tonalitatea optimistă și ponderat-modernă, interferează frecvent cu realismul social, ajungând chiar să prevaleze prin intermediul procedeelor ornamentale specifice. În cazul fațadei din strada Edgar Quinet nr. 6, deși, la prima impresie, predomină limbajul clasic în varianta clasicismului modern interbelic, tenta generală este Art Deco, în principal datorită manierei caracteristice de interpretare a repertoriului clasic. Schema compozițională a fațadelor se bazează pe clasica tripartiție orizontală - parterul tratat ca soclu, registrul principal (format din cele cinci etaje) și registrul coronamentului, aici minimal, reprezentat printr-o cornișă profilată simplă. Partiția orizontală, accentuată prin prezența copertinei, se articulează cu motivul de sorginte palladiană al porticului central decroșat (având, de fapt, la bază modelul Pantheonului roman), reprezentat aici de rezalitul celor trei arcade centrale susținute de pilaștri colosali cu capiteluri corintice stilizate. La ultimele două niveluri, câmpul central este ocupat de două registre de ferestre în arcadă, separate prin pilaștri scunzi cu capiteluri ionice, de asemenea, stilizate. Planul retras al fațadei este placat cu travertin la nivelul parterului, ritmat de cariatide, în timp ce restul suprafeței este riguros ordonat de grila stereotomică a rosturilor decorative, care scoate în evidență motivul central decroșat. Limbajul clasic este însă interpretat în cheia decorativist-ludică a esteticii Art Deco: ordinul colosal este aplatizat și își pierde sculpturalitatea în favoarea grafismului geometrizat, care se remarcă în special în tratarea capitelurilor; forța plastică a cariatidelor (în fragmentele păstrate), de asemenea aplatizate, este moderată prin stilizarea și modelarea formelor în planuri sintetice, iar rețeaua ordonatoare a rosturilor devine un adevărat pattern ornamental, care accentuează graficul în detrimentul tectonicului. Ca elemente specifice limbajului deco apar feroneriile decorative ale celor două intrări, care combină ornamente abstracte precum spirala (stilizare a vrejului), linia ondulată, festonul și octogonul; portalul flancat de elemente verticale în sfert de cilindru, tratate în benzi orizontale cu texturi alternate (marmură și travertin) și fine detalii sculptate; medalioanele decorative cu reprezentări simbolice legate de progresul societății, a căror retorică optimistă se înscrie în filonul realismului social (în cazul de față, trei modele repetabile ilustrând Industria, Agricultura și Comerțul prin intermediul unor motive consacrate – roata dințată, shedurile și coșul de fum, snopul de grâu, alături de clasicul caduceu); scrisul decorativ inspirat din grafica publicitară și, nu în ultimul rând, motivul modern al copertinei continue cu iluminare integrată. La interior, spațiile accesibile publicului au suferit modificări substanțiale în urma renovărilor succesive, dar păstrează încă unele savuroase detalii Art Deco, precum balustradele din fier forjat ale scărilor sau capitelul simplificat al unei semicoloane din holul de intrare. „Dialectul” de frontieră dintre Art Deco și clasicismul monumental, ilustrat de clădirea în discuție, se regăsește și la alte clădiri bucureștene de ținută, construite în timpul domniei lui Carol al II‑lea (imobilul din Splaiul Independenței nr. 5, arh. Nicolae Cucu, sau actualul sediu al Ministerului de Justiție, arh. Constantin Iotzu). Aceeași formulă este adoptată cu succes în cazul a numeroase edificii publice realizate în Transilvania în aceeași perioadă, cu intenția retorică de a exprima prestigiul și forța României reîntregite, păstrând însă o notă cordială și comunicativă (de ex.: lucrări semnate de George Cristinel la Sibiu și Cluj sau de Victor Smighelschi la Satu-Mare și Blaj). Însemnările de mai sus se vor a fi tot atâtea argumente în favoarea clasării clădirii din strada Edgar Quinet nr. 6 cu statut de monument istoric (recent solicitat de Observatorul Urban al UAR prin procedură de clasare în regim de urgență), în speranța că nu va împărtăși destinul nefericit al atâtor clădiri de patrimoniu, mutilate sau demolate sub pretextul inconsistent al progresului și modernizării. |

| On Edgar Quinet Street, across the street from Capșa, a peculiar building stands out in the continuous front formed by the tall apartment and office buildings. Even the most hurried traveler who doesn’t pay much attention to the urban landscape notices the five massive caryatids cut from the umbilicus up, of which only the lower part of their draped garments, stiff like flutes, and the peplum tied around their hips have remained. I haven’t found out their story but we can smile thinking about that petty party activist who, animated by a grim prudery and scandalized by the (possibly) naked busts of these géantes, proof of bourgeois rottenness, and by their blasphemous presence in the aseptic space of socialist morals came up with the idea of their beneficial mutilation.

However, upon closer inspection, the ground floor surprises us by the nobleness of the materials and their precious “accessories”; on the opposite side of the street we notice the discrete monumentality of a façade in the classical style, interpreted in a modern and refined manner. It is, in fact, a representative illustration of the architectural culture of the late inter-war period, namely that era of synthesis between the Art Deco aesthetics and monumental classicism. However, by comparing the historical plans with the current cadastral plan, one may assume that today’s edifice is a remodeling or a reconstruction of an older building, with a somewhat similar footprint. In fact, the central area of Bucharest boasts many buildings, especially from the XXth century, constructed on the foundations, cellars or load bearing structure of previous buildings, and their “modern” façades and volumetry are adjusted to the traditional planimetric types of urban vernacular architecture. What information does a brief research of the area and the street’s history provide? The section between Calea Victoriei and Academiei street is featured for the first time in the plans drafted by major Pappasoglu between1870 and 1875, under the name Strada Nouă. The small section pierced the old domain of great vornic1 Slătineanu, where functioned, as early as 1830, a theater (“Teatrul vechi” in Academiei St.) and the famous “Momolo” or “Slătineanu” ball room, with a pub and a confectioner’s shop on the ground floor, arranged in the very houses owned by the Slătineanu family, looking onto Mogoșoaiei Bridge, and later purchased by the Capșa brothers in 1868. By the end of the XIXth century, the two fronts of the new street came to complete one another, while the more important arteries around them kept their open regime. In the Plan of the Geographical Institute of the Army, drafted between 1895 and 1899, and the cadastral plan of 1911, the current plot located at No. 6, which already evinces the same form as today, is taken up by a U-shaped building with a planimetry characteristic of Bucharest urban vernacular architecture dating from the early XIXth century: a compact block arranged along the alignment and taking up the entire width of the plot, articulated with two perpendicular bars at the rear, to which the appurtenances are added, at the rear part of the plot. The building, with a ground floor and an upper floor, can also be seen in the aerial photographs taken in 1927 by Compagnie Aérienne Française. If stylistically the current six-storey building undeniably pertains to the classicizing aesthetics of the 1930s, the footprint in the cadastral plan betrays the obvious traces of previous periods (which calls for archive, as well as field research): the same compact block facing the street, slightly more developed in depth and articulated on the west side of the plot, with only one secondary block, narrower and shorter. The two, which could have been erected along the outline of part of the old building, are joined by another narrow block at the rear of the plot, in the place of the appurtenances. The new building, benefiting from its location in an active city area strewn with institutions and business premises, was conceived from the start as an office building – as confirmed by the 1934 Official City Guide which featured, opposite the address Edgard (sic!) Quinet No. 6, Albina Bank, as well as the Kodak Society. The association of these two headquarters could account for the asymmetrical compositional scheme of the façade, probably corresponding to the spatial-functional needs of the interior: the two access ways, with varying degrees of importance, arranged on the ground floor, lead to bays on the upper floors, also varying in terms of dimension and treatment, which frame the central motif. Additionally, the figurative decoration of the portal on the right – beehives and bees – explicitly states the identity of one of the building’s occupants. Returning to the façade which perfectly fits in the continuous street front, while standing out on account of its plastic treatment, one can note its cheerful monumentality, devoid of ostentation, but also elegant and even sophisticated. All these characteristics have merged successfully because of a clever fusion between the classical language, preferred at the time for public buildings with representation functions, and the Art Deco aesthetic, favored for office buildings and apartments, for hotels and commercial premises, for entertainment and recreational establishments. The recovery of the classical paradigm in the 1930s has a double explanation. On the one hand, the entire post-Belle Époque period was characterized by a classicizing trend (summarized by Jean Cocteau in the formula retour à l’ordre), which appeared as a legitimate reaction to the formal excesses committed by late academicism and the “1900” styles, as well as to the challenging experiments proposed by the avant-garde. On the other hand, the generalized crisis manifest in the inter-war period was translated aesthetically in the appeal to the morals, rigorousness and austerity evoked by classical values, and from a political-economic standpoint, in the tendency to strengthen the authority of the state, materialized in the monumental architecture of public institutions, whether they belonged to dictatorial or democratic regimes. The embracing of academic classicism, accompanied in plastic arts by a propagandistic kind of realism, expressed the need for concrete [self]representation, intelligible for the large masses, of the State Power and of the order imposed by it on society – hence the generic name “social realism” given to this intensely ideological culture. The solemn discourse of monumental classicism is often well mitigated by the sthenic, aestheticizing “background noise” of Art Deco language, turning towards a stylistic expression that we can call “deco classicism”. The two terms of the phrase are not contradictory: as a soft facet of inter-war modernism, the deco phenomenon promotes tolerance, even reverence, for tradition, in addition to communicativeness and the primacy of immediate aesthetic pleasure over abstract principles, which explains the success it enjoyed at the time. In fact, Art Deco aesthetics, by its optimistic, moderately modern tonality, frequently interfered with social realism, and sometimes gained the upper hand, by means of specific ornamental procedures. In the case of the façade of the 6 Edgar Quinet house, although at first glance one might think that the classical language, in its inter-war modern classicism version, prevails, the general tendency is Art Deco, mainly due to the characteristic interpretation of classical repertoire. The compositional scheme of the façades is based on the classic horizontal tripartition – the ground floor treated as a pedestal, the main register (consisting of the five floors) and the register of the coping, here minimal, represented by a simple profiled cornice. The horizontal partition, emphasized by the entrance covering, is articulated with the Palladian-inspired motif of the central detached portico (actually based on the model of the Roman pantheon), here represented by the jutty of the three central arcades supported by colossal pillars with stylized Corinthian capitals. On the uppermost two floors, the central field is taken up by two arched windows separated by short pilasters with Ionic capitals, also stylized. The receding plan of the façade is plated with travertine at ground floor level, and rhythmically decorated with caryatids, while the rest of the surface is rigorously ordered by the stereotomic grid of the decorative joints, which highlights the central detached motif. However, classical language is interpreted in the decorative-ludic key of Art Deco aesthetic: the colossal dimension is flattened and loses its sculptural quality in favor of a geometrically ordered graphism especially to be seen in the treatment applied to capitals; the plastic force of the caryatids (in the preserved fragments), also flattened, is moderated by the stylization and modeling of forms in synthetic planes, and the ordering network of the joints becomes a genuine ornamental pattern, which emphasizes the graphic dimension to the detriment of the tectonic. As elements specific to the art deco language, we can list the decorative iron work at the two entrances, which combine abstract ornaments such as the spiral (a stylization of the creeping stalk), the undulating line, the festoon and the octagon; the portal flanked by vertical elements enclosed in cylinder quarters, treated in horizontal stripes with alternating structures (marble and travertine) and fine sculpted details; the decorative medallions with symbolic representations relating to the progress of society, whose optimistic rhetoric pertains to social realism (in this case, the three recurrent models illustrating Industry, Agriculture and Trade by means of established motifs – the cogwheel, the sheds and the chimney, the sheaf of wheat, next to the classical caduceum); the decorative writing inspired by advertising graphics and, last but not least, the modern motif of the continuous entrance cover with integrated lighting. Inside, the spaces accessible to the public underwent substantial changes following successive renovations, but still preserve several delightful Art Deco details, such as the wrought iron railings of the stairways or the simplified capital of a semi-column in the entrance lobby. The border “dialect” between Art Deco and monumental classicism, illustrated by the building at issue, can also be seen at other prestigious Bucharest buildings, built during the reign of Carol the IInd (the building at 5 Splaiul Independenței, designed by architect Nicolae Cucu, or at the current headquarters of the Ministry of Justice, by architect Constantin Iotzu). The same formula had been successfully adopted at numerous public edifices constructed in Transylvania during the same period, with the rhetoric intention of expressing the prestige and force of unified Romania, while preserving a cordial, communicative note (for instance, works signed by George Cristinel in Sibiu and Cluj or by Victor Smighelschi at Satu-Mare and Blaj). The above observations will prove to be just as many arguments in favor of classifying the building at 6 Edgar Quinet as historical monument (recently requested by the Urban Observatory of UAR by means of the emergency classification procedure), in the hope that it will not undergo the unhappy destiny of so many heritage buildings, mutilated or demolished under the unsubstantiated pretext of progress and modernization. |