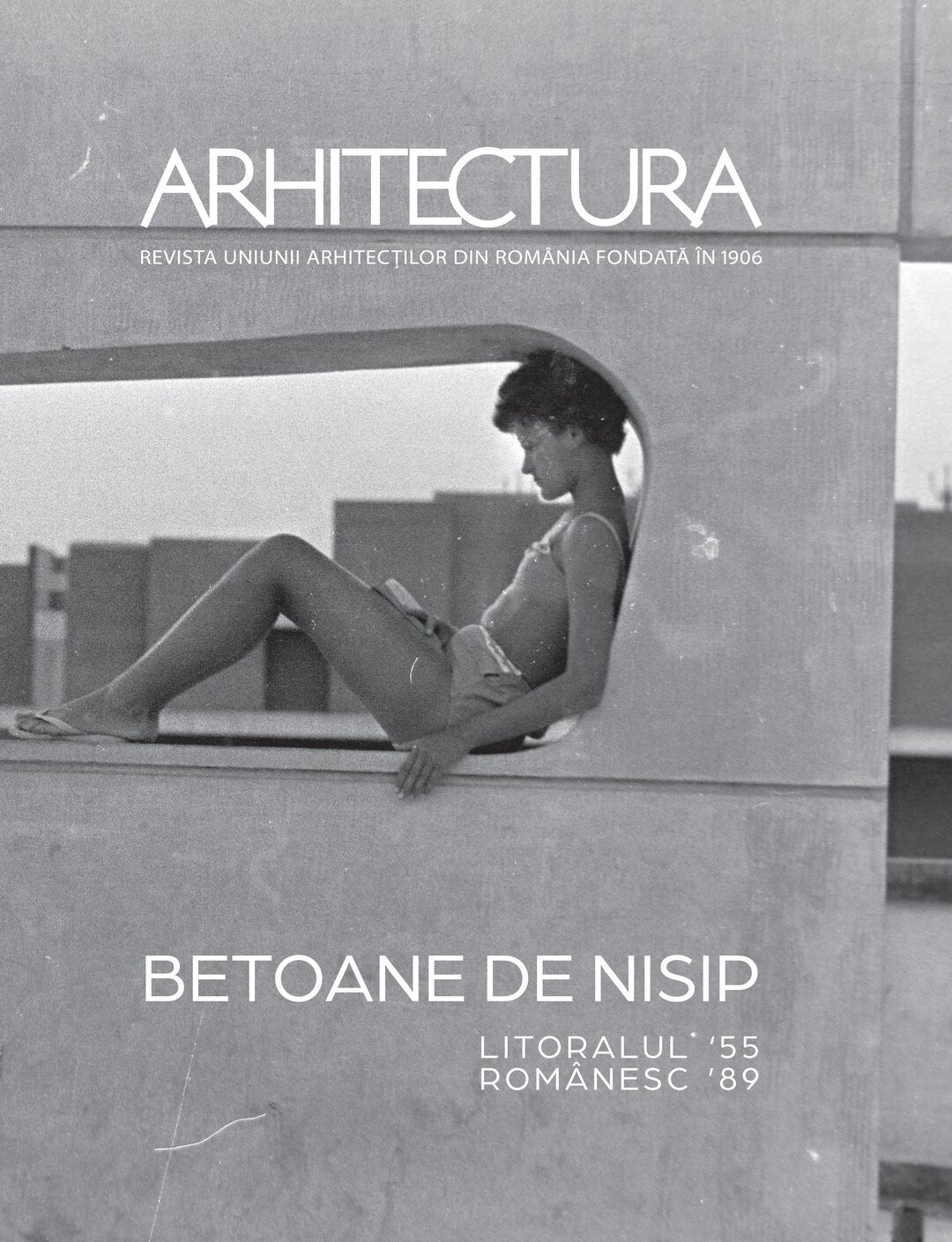

Costinești Sculpture Camp

Concrete wings

Seaside. A published chronology

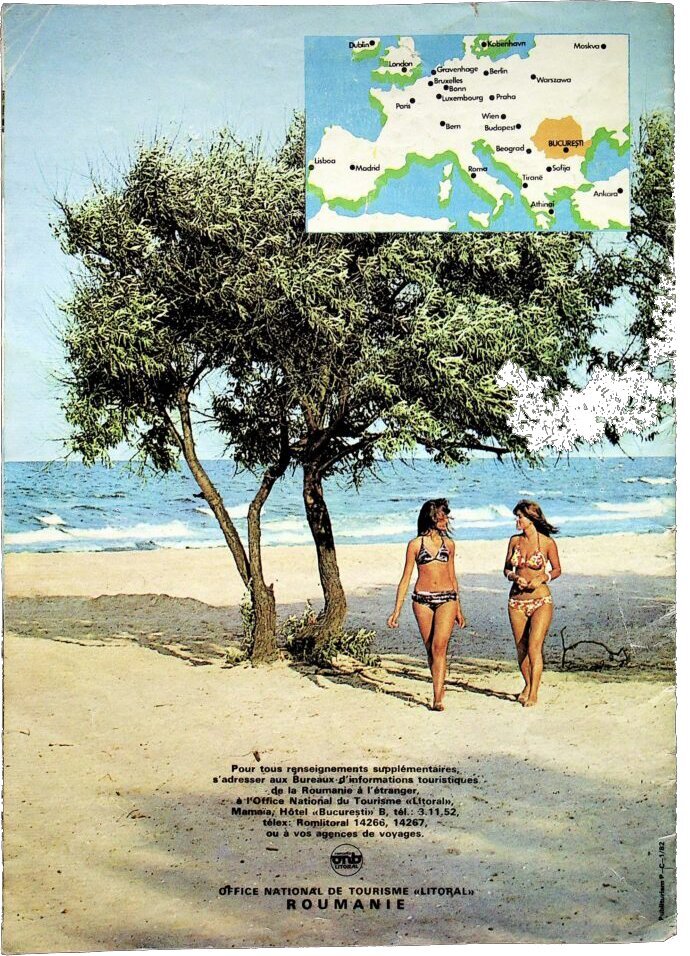

Littoral, a (com)promised land

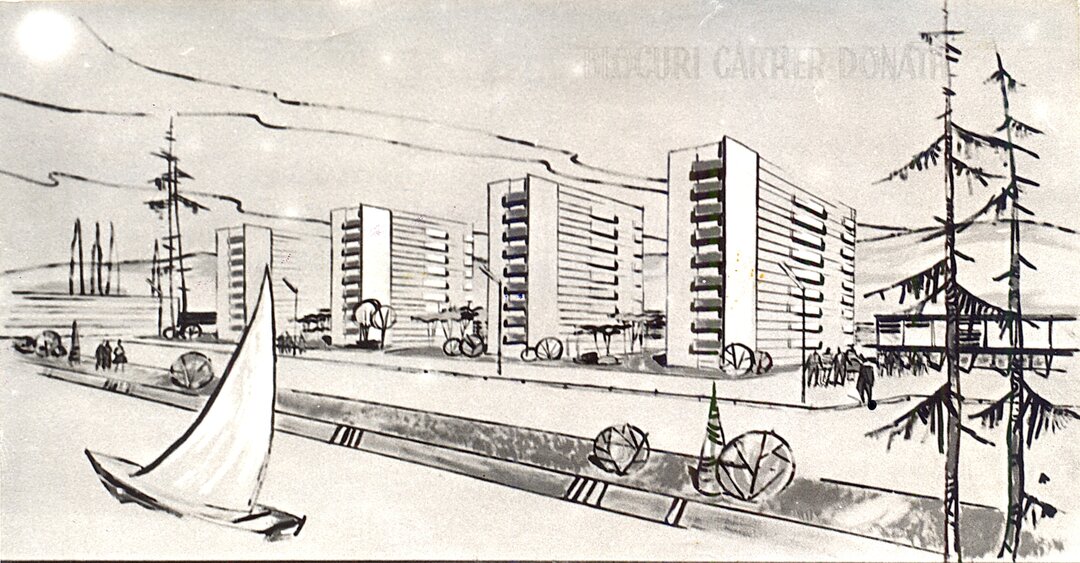

The post-war Romanian coastal project: a call for a transregional critical history

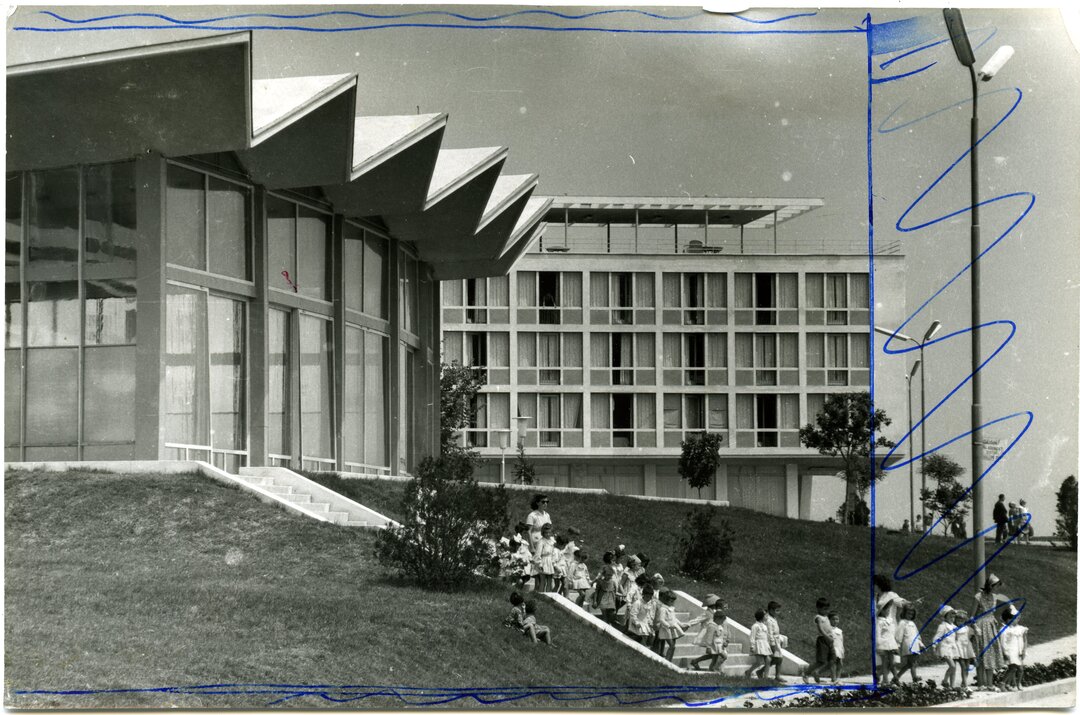

Mamaia as a model: the 'radiant' housing estate of the 1960s

Closed at the pub - or the contemporary failure of socio-cultural amenities

Bureau for Art and Urban Research (B.A.C.U. Association)

Archives in the visual arts Case study Coastline Archives

Thoughts about Littoral

Mass tourism and special villas

Local, symbolic and precarious or Learning from Vama Veche

SouthSouth

Seaside tourism, leisure and dance from 1948-1989

Interactions, cosmopolitanism and modernity on the Romanian coast in the 1960s-1970s

In search of the lost Costinești

Architects and architecture at the Danube-Black Sea Canal - personalities, fragments, memory

Observations on the history of landscape architecture on the Romanian coast

Beach development in Mamaia resort

The new-old Mangalie, always the same bone of contention among architects

A golf with swans

Interview with Răzvan Lăzărescu

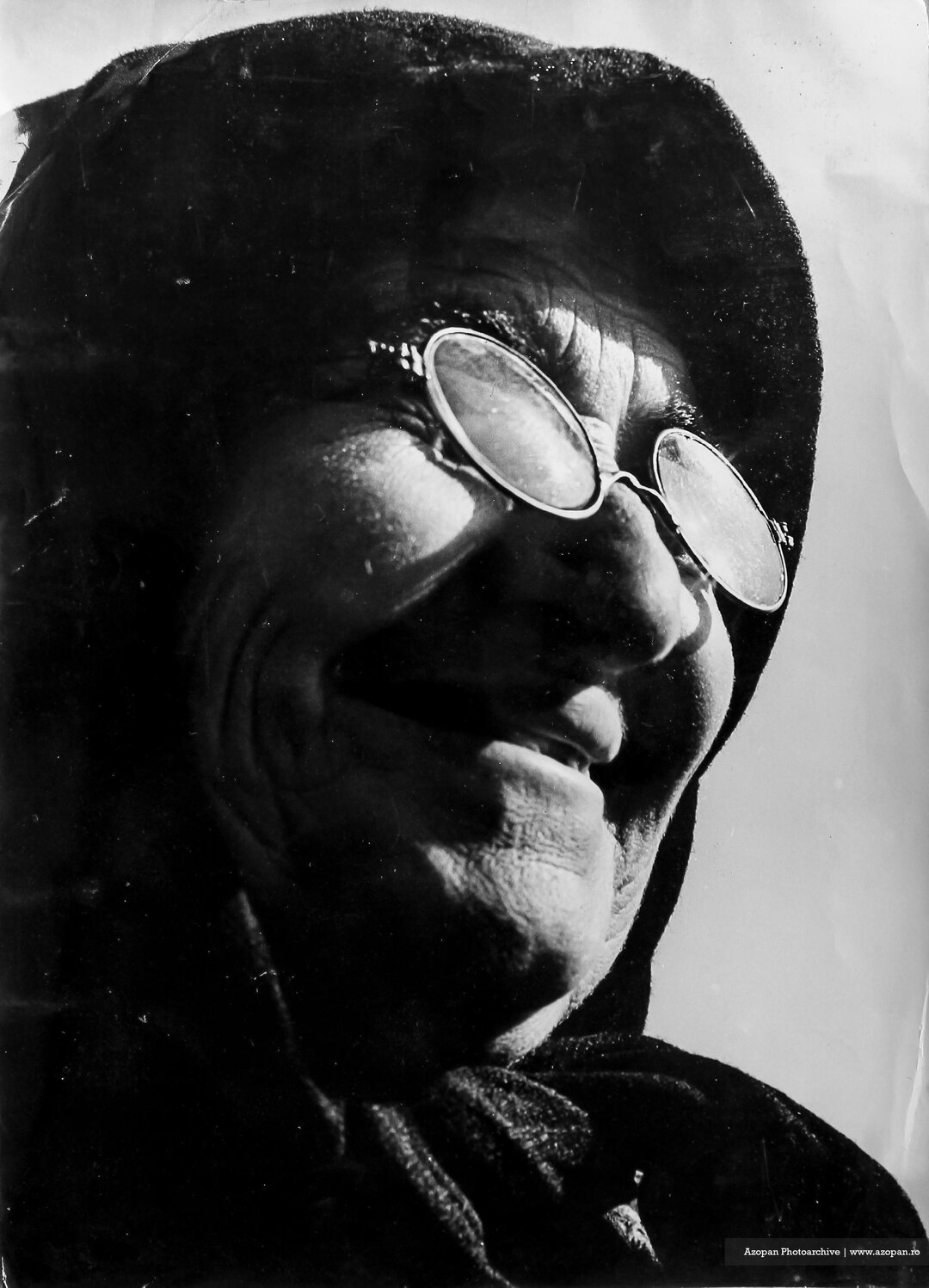

Dad

Concrete wings

Enchanting views

Why do we still go to seaside resorts?