11,000 sirens

What water doesn't bring, the winds bring

If it is true that we humans have much more in common than the air we breathe, then the people of Braila have in their subtle, timeless memory the seeds of all the emotions of departures and adventures, of the call of far away places, of impatience and longing. If you don't believe me, remember the sound of a ship's siren leaving port! In Brăila I could hear them from home, from school, from the street, and they took me with them on their boats, and I floated down the Danube to the sea, and then from sea to sea to the end of the world. There were no longer 11,000 ships a year, like in the days of the porto-franco when the world price of wheat was fixed in Brăila, but there were still enough sirens to keep the dream alive.

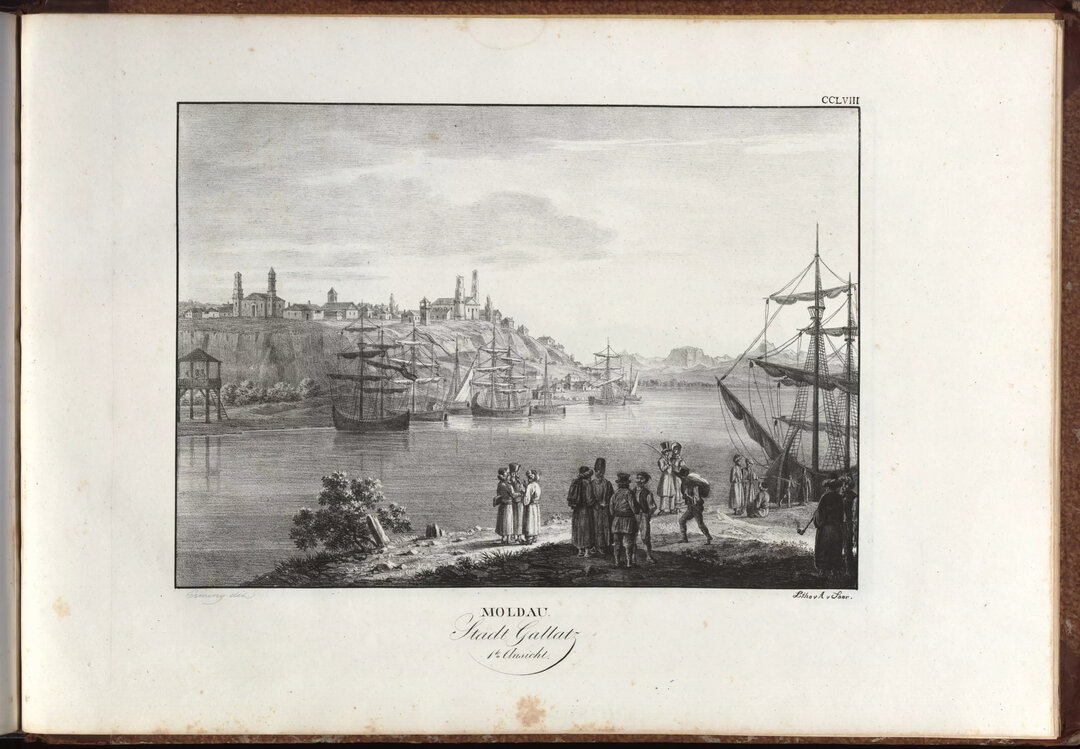

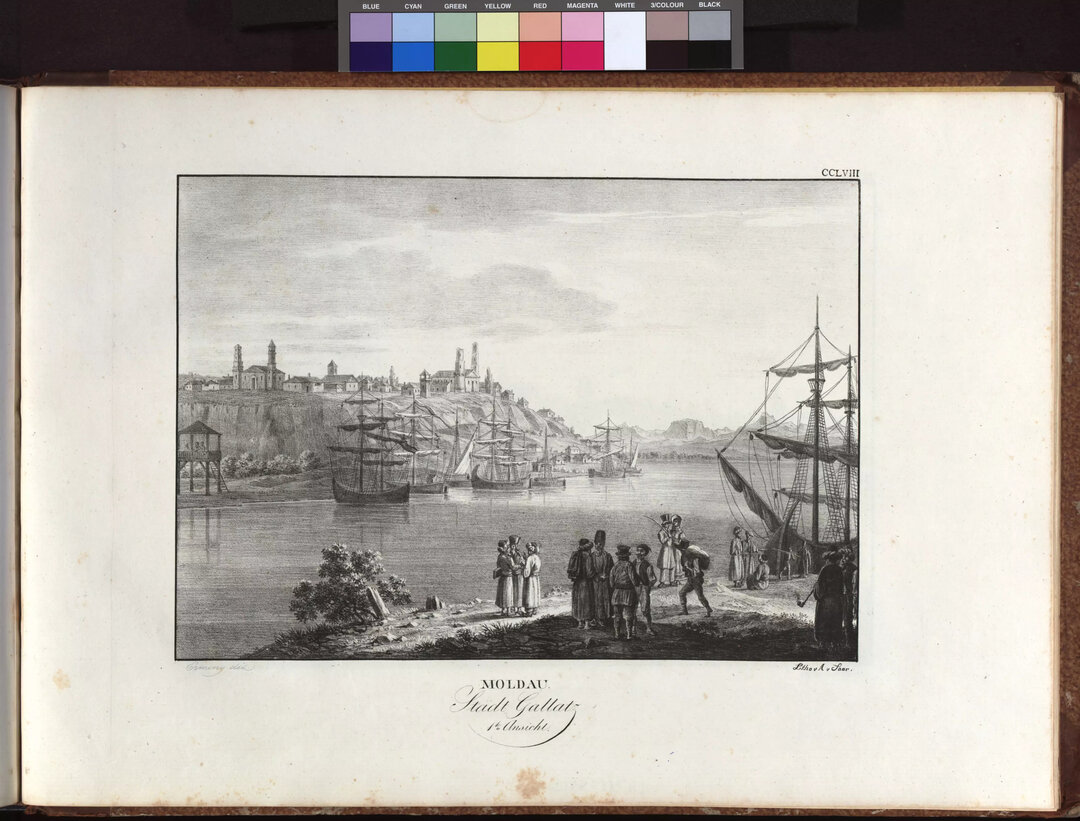

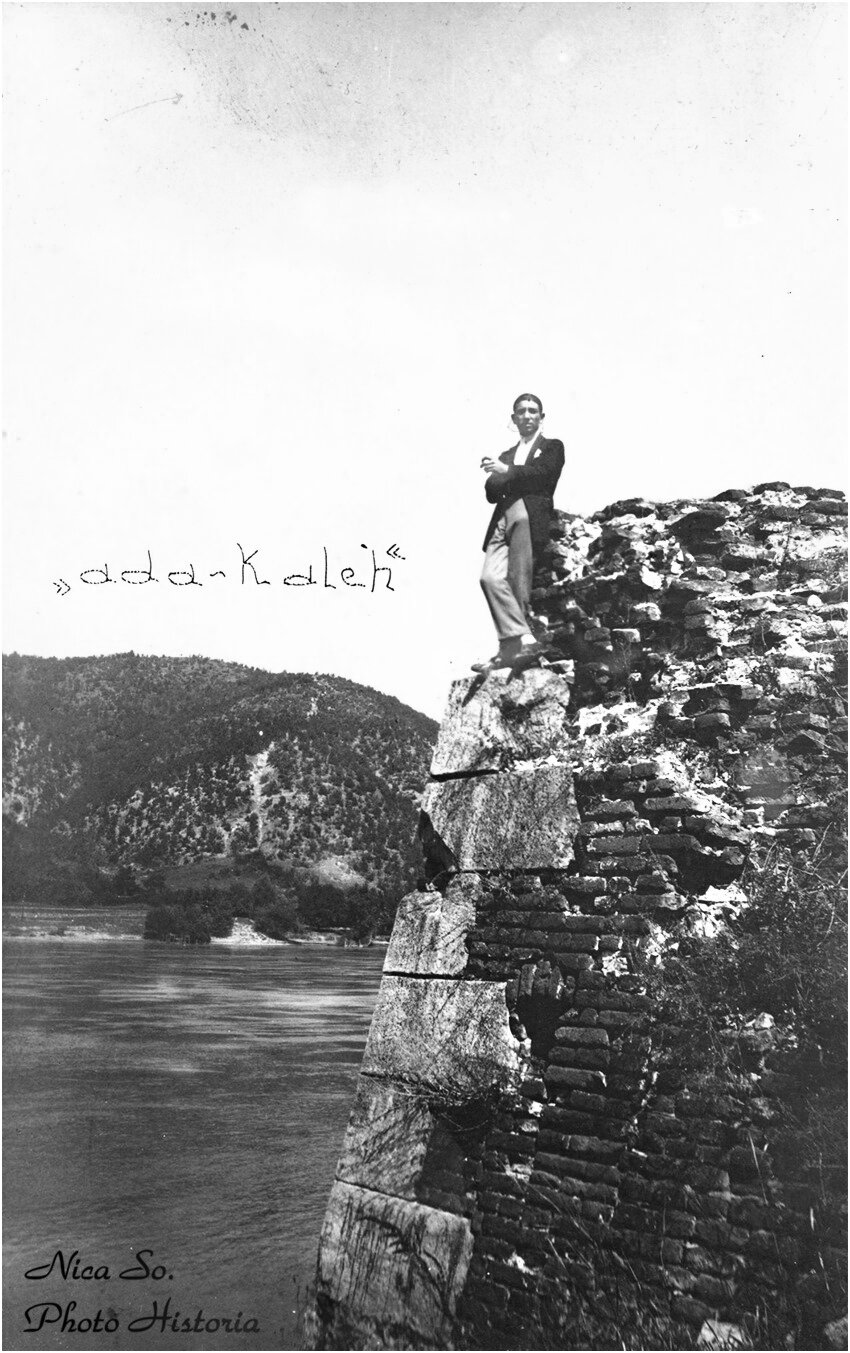

As a child I was convinced that all people and all things came to us by boat. The large granite blocks that paved the sidewalks of Brăila had at one time been in the belly of a ship that had come from far away to Brăila to load wheat harvested from the immense plains or perhaps flour from the Violatos mill, a six-storey colossus that also ground 150 tons of grain a day and from whose storehouses the flour flowed to the river through an underground tunnel.

And surely the boat had also come through the Dardanelles with little Aunt Greta, my mother's friend, who sat for three Turkish days on a large piece of silk stretched over a layer of sheep's wool from the pool's machidens, and with mesmerizing dexterity handled curved needles, leaving behind her a grotesque quilt with double and triple stitches like long, magical silk threads. And the machidonilors from the puddle with their stalls also came to the city by water, by ferry, and filled the markets with 'good cheese from Brăila', as white as milk, as fat as butter and necessarily sprinkled with negrilică - that black cumin, miraculous healing seed, which is said to have been found in the tomb of Tutankhamun. And this black seed, haba al-barakah, also by water, came all the way from south-west Asia, presumably through the pockets of a sunburned sailor, to make the first flowers - as white as it was black - on the banks of the Danube.

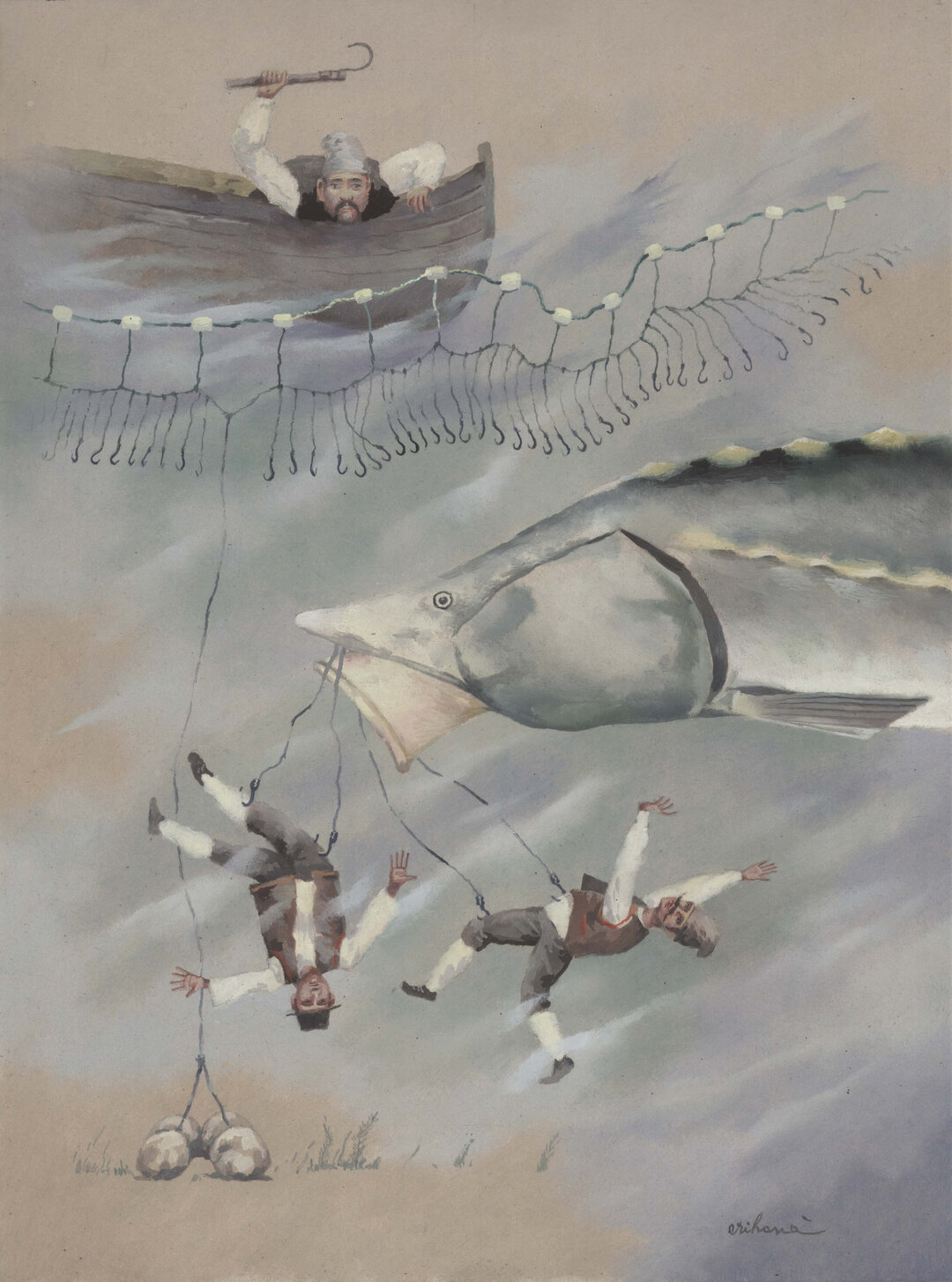

And the Danube brought so much more, from the huge barrels of olives of all kinds prepared in all sorts of ways, to the silver scrumbia that confirmed spring and heralded the Easter celebrations, for on the first day of Easter, in Brăila, the whole town smelled of scrumbia. People came from the churches, from one of the more than 25 churches, and ate scrumbie bought from the fishermen of the Lipopovenes and grilled. At the table with their Machidonian friends, and the Lypovs, and Turks, and Greeks, and whatever else they were, they ate kippers and cheese with green onions and olives, and lamb drob, and lamb drob, and cozonac, and baclavale, and sarailii, all greeting each other with "Iasu". The old people used to say that, before the war, Braila had about 60,000 inhabitants. And there was a law which said that a town of up to 100,000 inhabitants was not allowed to have 600 pubs. Brăila had 599. And how could it not be so in a thirsty port, where cheese and salted fish and olives were on the house, and the songs were about Chira Chiralina and Codinus and Terente?

Also on the Danube, around 1914, a 16-year-old French girl had arrived in Brăila, having run away from home with a sea captain. When I met her, Mademoiselle Antoinette was small, frail, lonely and very old, smelled of Chanel 5 and was giving French lessons on a Mauger - also perfumed and carefully bound in cloth covers - leafing through a very old issue of Marie France for I don't know how many times. The only one she had. Mademoiselle lived in the Rue Plevnei, near the Royal, in a large house with very high ceilings. She had tenants brought in by ICRAL and the once obviously beautiful house was now in a sad state. But nothing prevented Mademoiselle Antoinette from treating you royally, barely walking through the door with an enormous silver tray on which were a delicate cup of acacia tea and a poppy pretzel from the traveling simigons. From time to time she announced that she was selling another linen of brilliant white silk damask. Where was that marvel of fine cotton and silk jacquard woven? Perhaps still where a wealthy Greek shipowner had commissioned his stained-glass window of Hermes, now completely restored in the hall of the Embericos House, a jewel erected in 1912 by the architect Predinger and today housing the Nicapetre Museum, for Hermes is much more than the God of Trade, and a local newspaper in 1840 was already called Mercury.

The city's streets run from the Danube in an arc and back to the Danube, and the map of Braila looks like a spider's web with anchors. The city's old trees, plane and acacia, grow more majestic every year. At one time, a literature-loving mayor planted many linden trees in the 'Willow City'. Mihail Sebastian was no more, and the people of Brăila turned up their noses, but the winds beat them all the same, for in Brăila, what the water doesn't bring, the winds bring. In winter, the Crivățul gales, eroding everything from the rocks of the Măcinului Mountains to the snowflakes, which leave only a sort of splinters that sliver your face. Spring is often the time of Băltărețul, which carries the rains and the scents of the 'reborn pool' and the memory of Mihu Dragomir, the poet of kisses tasting of blackberries. Then it is summer and the 'Black Wind' blows, the one also called the 'Empty Bag' because it burns and dries everything in its path, and then goes to play cynically with the 'Bărăgan's Thistles', those whom Panait Istrati loved 'to the point of dementia'.

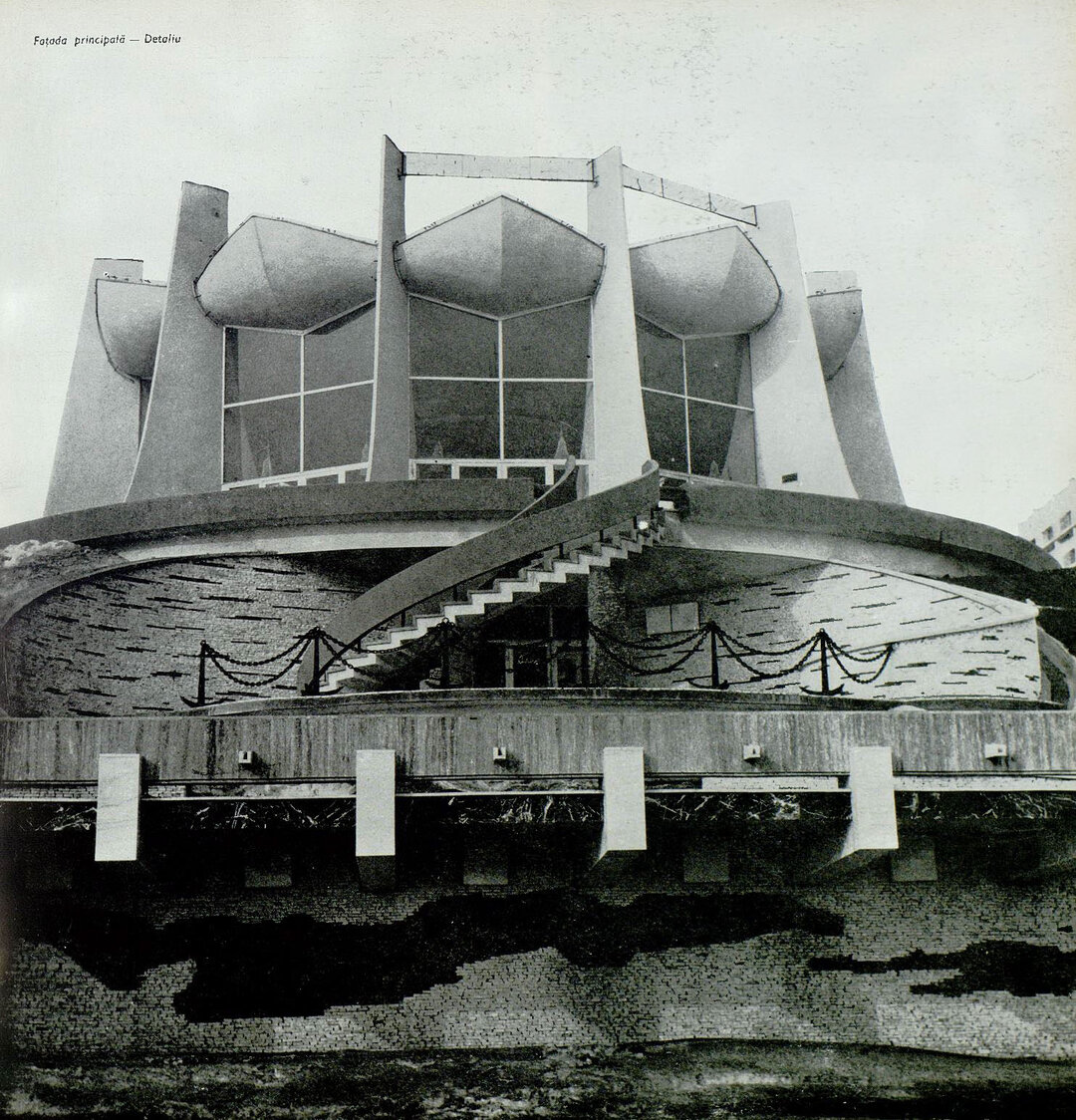

The scorching city has no escape except in the water. In the Danube, or right next to it, at the floating swimming pool or on the other shore, at Perla beach or Corotișca lakeside. You inevitably hear the dice rolling and the wind through the arching willows. The Danube seems to flow noiselessly, only if you swim in it is still a wild roar twisted by anaphora. And then, out of nowhere, a siren breaks the silence and rekindles longing, and distances, and dreams.

There were no longer, in my childhood, 11,000 ships a year, as there were when Rally ordered the heavy velvet curtains of garnet-colored velvet embroidered with gold for the theater where Sarah Bernard and Maria Filotti were to play. And today there are hardly any, because the cruise liners from Vienna pass at night through the former great harbor, which the modern-day "housekeepers" have not found a way to build a pier. Maybe 4 or 5 more ships, 4 or 5 sirens still sounding... I would like to conclude with the words of Fănuș Neagu: "I believe in the future of Braila. It, being drowned by the plain, might find its salvation as a floating city".

-topaz-denoise-enhance-sharpen--15883-m.jpg)